Tags

A.A. Milne, Apollonius, Arthur Rackham, Beowulf, Chrysophylax, Cressida Cowell, Dragons, Drawn From Life, Drawn From Memory, Dream Days, E.H. Shepard, Edwardian, Farmer Giles of Ham, How to Train Your Dragon, Kenneth Grahame, Maxfield Parrish, Nine Dragons, Now We Are Six, Octavian, Prince Valiant, Renaissance, Sir Gawain, Smaug, St. George and the Dragon, The Argonautica, The Hobbit, The House at Pooh Corners, The Reluctant Dragon, The Wind in the Willows, Tolkien, Victorian, Walt Disney, Western Medieval, When We Were Very Young, Winnie the Pooh

Welcome, dear readers, as always.

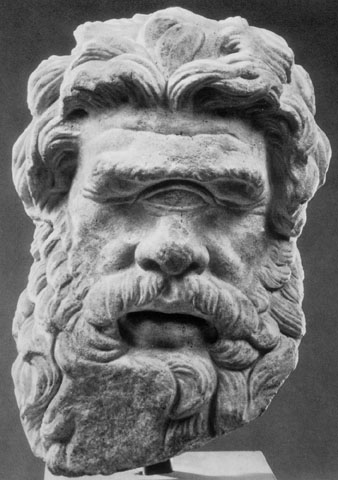

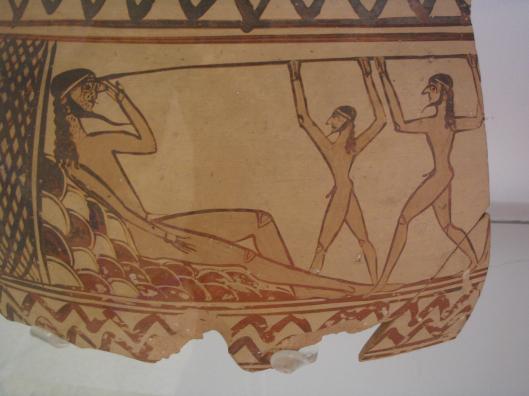

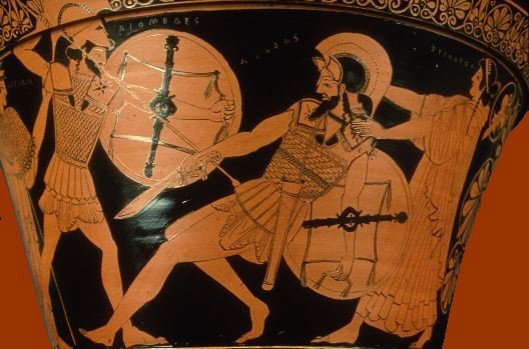

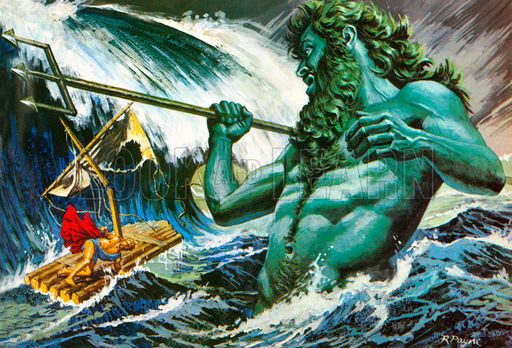

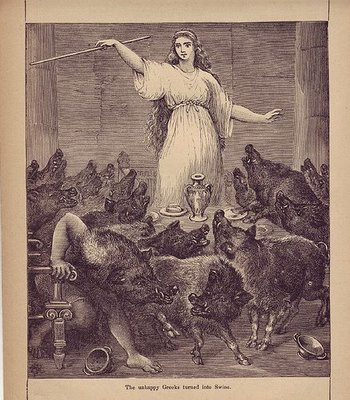

One of us is in the midst of creating a course for the fall term. It’s called “Handling Monsters: A Handbook” and several of those monsters are dragons—the “Sleepless Serpent/Dragon” of the ancient Greek literary epic by Apollonius, The Argonautica,

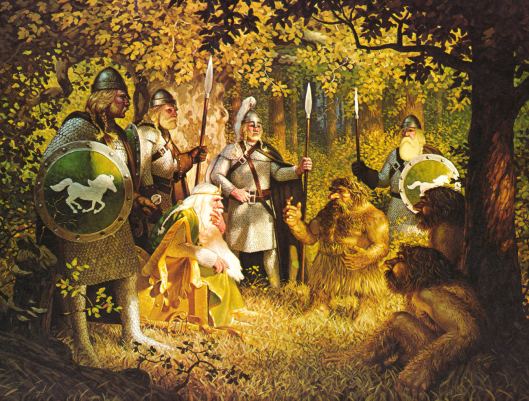

the dragon which Beowulf fights,

(when small, we always imagined this as looking like the one which Sir Gawain, Prince Valiant’s master, fights)

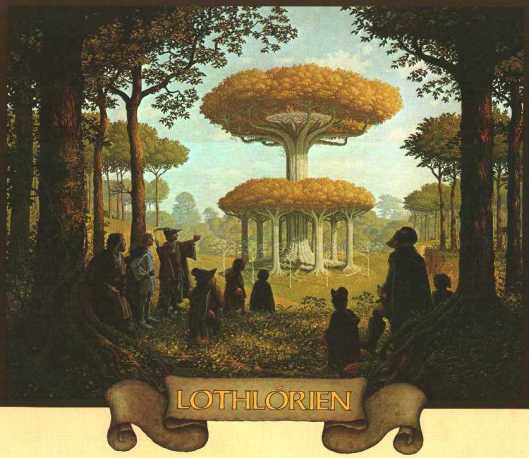

Smaug,

and Toothless, from How to Train Your Dragon (by Cressida Cowell—there’s also a movie by that name, which is fun—great flying scenes–but it’s so different from the book that it really should have another title!)

We must confess that we’ve never been big saurian fans, either dinosaurs or dragons, but, as monsters go, they have their uses. Saying that, however, we do have to add that we’ve always loved the “Nine Dragons” scroll, a 13th-century Chinese painting…

[And here’s a LINK to a site at the Center for the Art of East Asia which you can see the whole scroll—well worth the visit—and revisit, if you’re like us and love Chinese painting.]

While putting together this course, we’ve been spending some time gathering dragon images. Sometimes, they seem pretty fantastic—painters with wild imaginations—

And sometimes they look like someone once saw a crocodile.

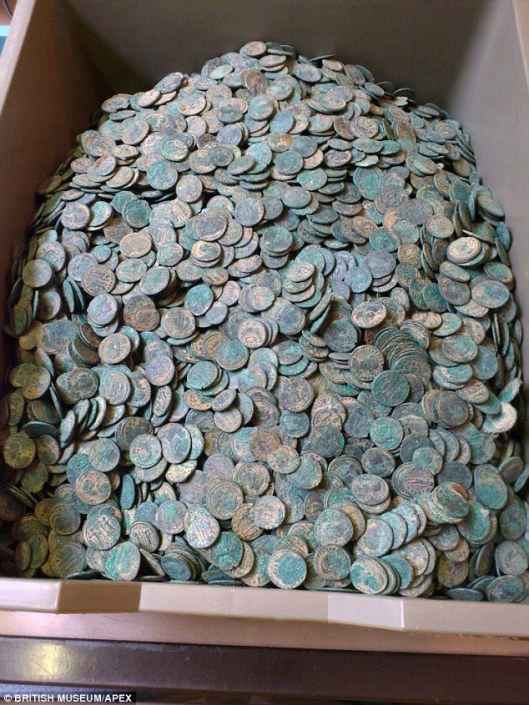

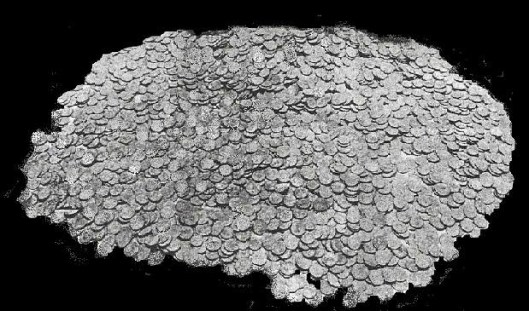

[Perhaps on an old coin? For example, Octavian—the Emperor Augustus-to-be—after the defeat of Antonius and Cleopatra, issued this coin, which reads “Egypt Taken”,

suggesting that, when a Roman thought of Egypt, it wasn’t the pyramids which came to mind, but a scaly, many-toothed amphibian!]

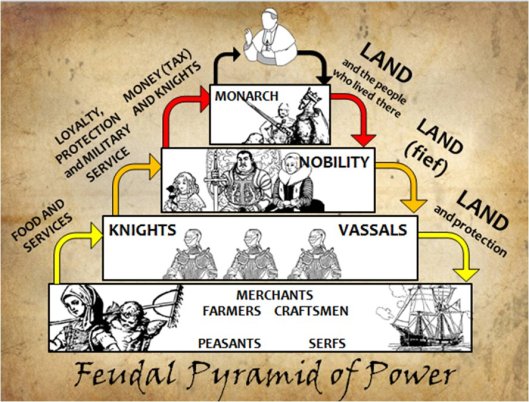

And the image before the coin reminds us that, in Western medieval/early Renaissance art, a major source of dragon pictures is religious, being depictions of St. George and his dragon-slaying.

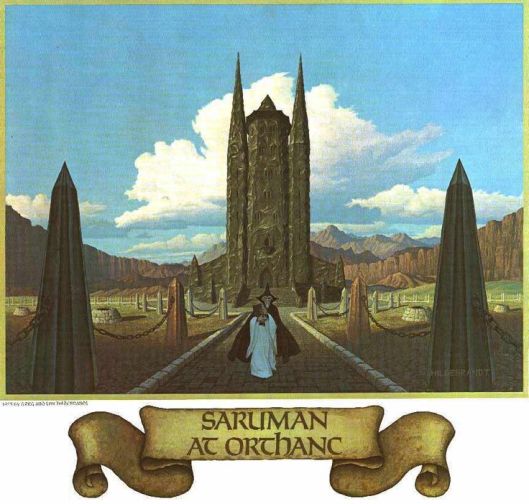

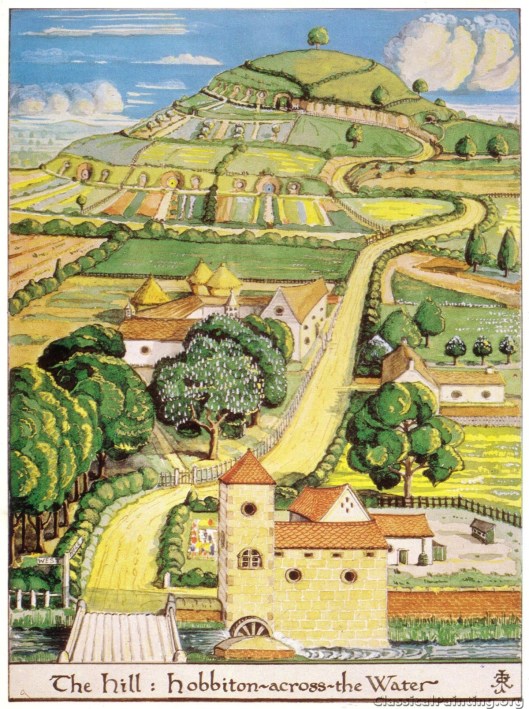

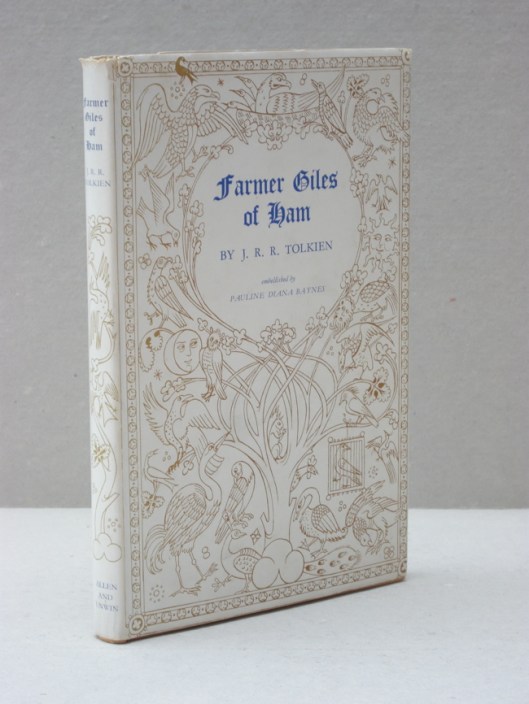

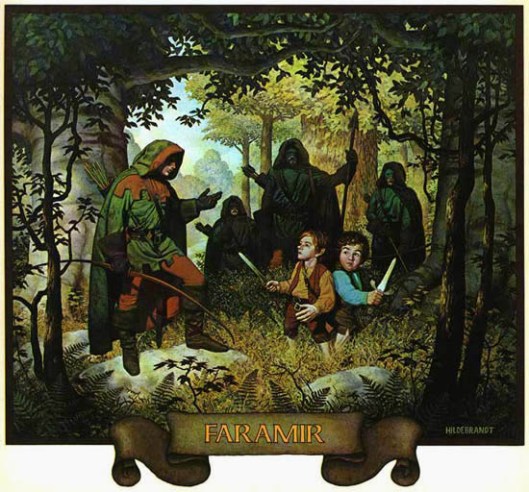

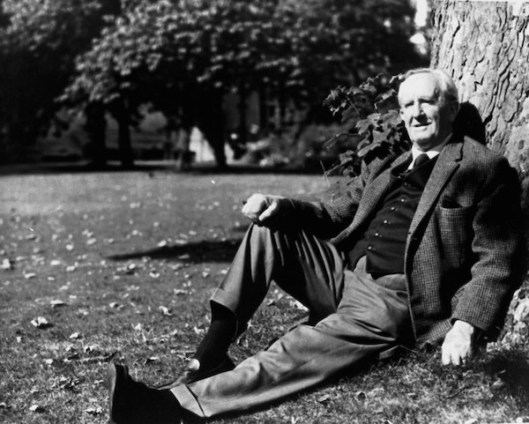

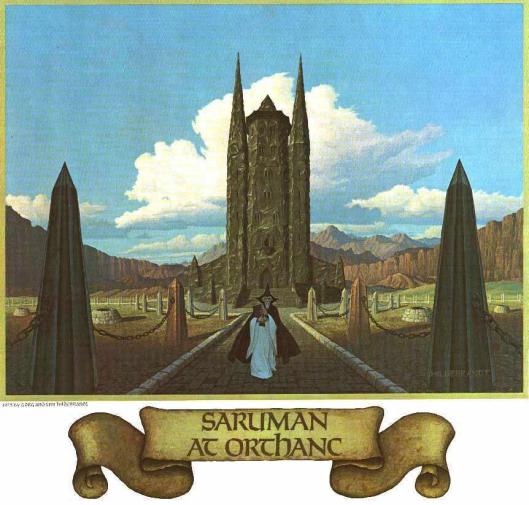

We’ve mentioned JRRT and Smaug, but that it only his first dragon story. There is another, Farmer Giles of Ham, written in 1937 and published in 1949.

If you haven’t read it, we recommend it as a look at JRRT at play, more Hobbit than Lord of the Rings. The story is about a very practical, but hardly adventurous farmer, Giles, who, after chasing off a giant from his village, is given the job of dealing with an invading dragon, Chrysophylax (maybe something like “Watchman of the Gold”).

Although the dragon is tricksy, Giles eventually overcomes him with a combination of shrewdness and a famous sword, Caudimordax (“Tailbiter”). In the process, he becomes not only wealthy, but also founds his own kingdom-within-a-kingdom. As well, though JRRT, more than once in his letters, lets us know that he is not an enthusiast for democracy, he provides a very critical view of monarchy and its pretensions. (This may also explain why, although those in the Shire may refer to “the king” and “the rules”, which presumably came with that monarch, their own local form of government is more familial than bureaucratic.)

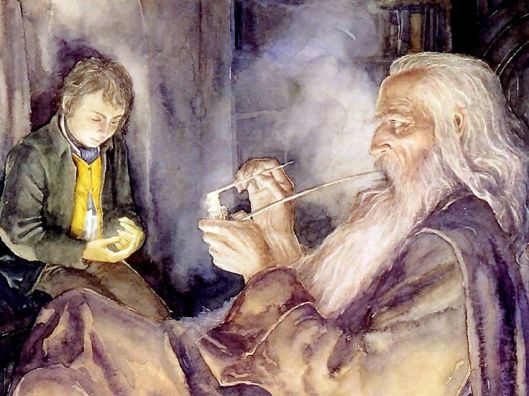

Chrysophylax is chatty, rather like Smaug, but there is a much lighter touch here, and Chrysophylax reminds us of our favorite dragon after Tolkien’s, the unnamed dragon in Kenneth Grahame’s

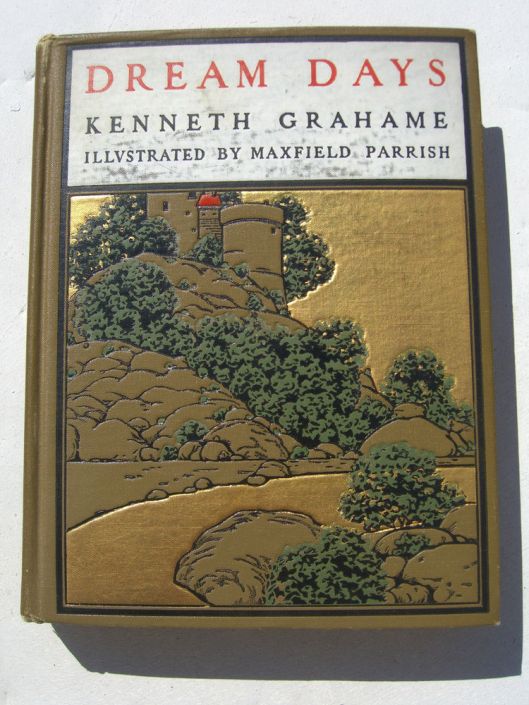

short story, “The Reluctant Dragon”, from his 1898 collection, Dream Days.

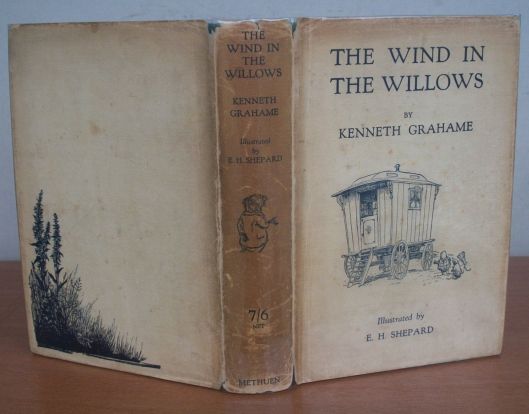

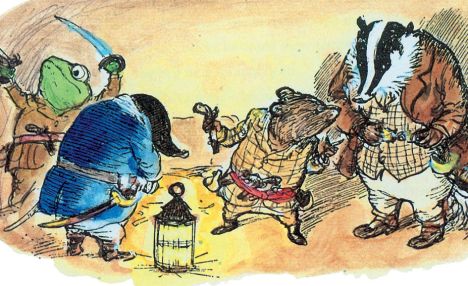

If you recognize Grahame’s name, you probably know it from his 1908 novel, The Wind in the Willows, with its well-known characters, Toad, Rat, Mole, and Badger—not to mention the wicked weasels!–

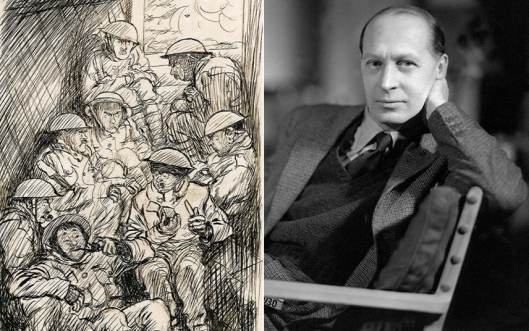

first illustrated by E.H. Shepard

whom you may also know as the illustrator of A.A. Milne’s Winnie the Pooh, The House at Pooh Corners, When We Were Very Young, and Now We are Six.

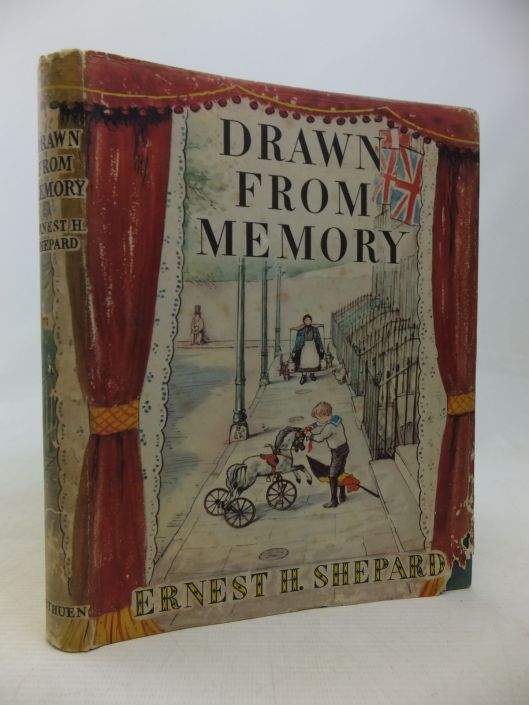

[Shepard also wrote two volumes of autobiography—which he illustrated, of course—Drawn from Memory (1957) and Drawn from Life (1961)

and, for a picture of a growing up in the later Victorian world, beautifully written and illustrated, we very much recommend both.]

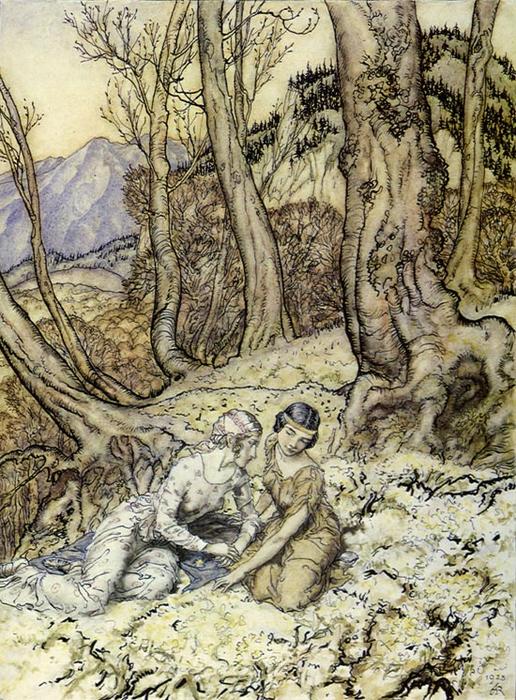

[And a second footnote here: Arthur Rackham—one of our favorite late-19th-early-20th-century illustrators– also illustrated The Wind in the Willows,

his last project before his death in 1939. It was published a year later, in 1940.]

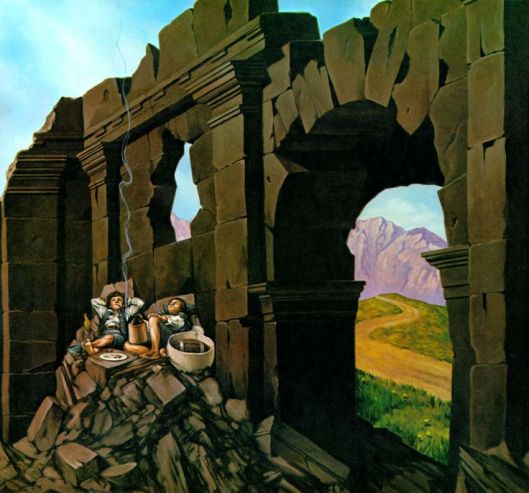

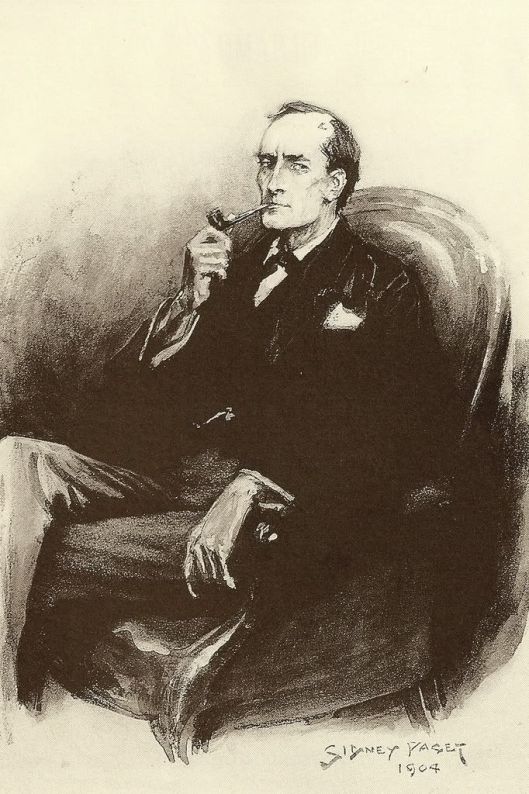

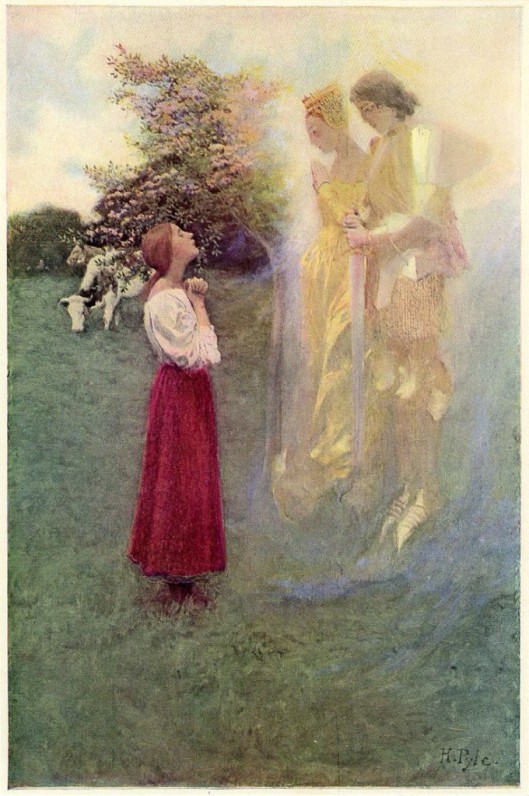

The title gives away a great deal of the plot of Grahame’s “The Reluctant Dragon”. Instead of being a murderous hoarder, like Beowulf’s dragon, or Smaug, this is dragon-as-pacifist, (as depicted by his original illustrator, Maxfield Parrish):

not in the least interested in plundering and burning, but rather in viewing sunsets and living a peaceful existence—until St. George appears. As to what happens next, we’re not going to issue a spoiler alert here, but rather provide links to three works by Grahame: two collections of stories and essays, The Golden Age (1895), Dream Days (1898), and The Wind in the Willows (1908), inviting you to read for yourself and to enjoy Grahame’s elegant Edwardian prose and gentle approach.

With thanks, dear readers, for…reading.

MTCIDC

CD

PS

Walt Disney studios made cartoons of “The Reluctant Dragon” (1941) and “The Wind in the Willows” (1949), which are currently available in Disney collections. They both stray rather far from the original stories, but are fun in themselves (and Eric Blore’s voice is perfect for “the handsome and popular Toad”).

PPS

One of us has written what we might immodestly call a very good short story based upon Arthur Rackham’s last days and his determination to finish his illustrations to The Wind in the Willows before his death and we plan to publish it here next week as a kind of “Summer Holidays Extra”. We hope you’ll enjoy it.

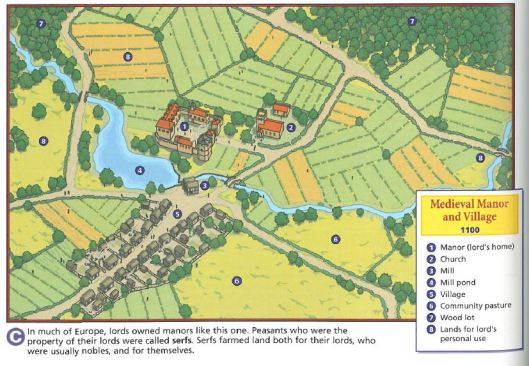

In our medieval world, such bells had a number of functions. Not only did they ring the hours of the medieval Christian day, but they could also sound a warning, called the “tocsin”, and signal that the day was over and that fires should be covered for the night, the “curfew”—rather like the “sun-down” bells in Minas Tirith. Joan of Arc (c.1412-1431) said that she could sometimes hear the sound of angelic voices, inspiring her to drive the English out of France, in her village bell.

In our medieval world, such bells had a number of functions. Not only did they ring the hours of the medieval Christian day, but they could also sound a warning, called the “tocsin”, and signal that the day was over and that fires should be covered for the night, the “curfew”—rather like the “sun-down” bells in Minas Tirith. Joan of Arc (c.1412-1431) said that she could sometimes hear the sound of angelic voices, inspiring her to drive the English out of France, in her village bell.

(As usual with so many old and established things, there is argument over where the word “penny” comes from. Personally, we’ve always imagined that it’s an English diminutive of a Brythonic word—as it exists today in Welsh—“pen” = “head”, the idea being that coins had portrait heads on them. Certainly some pre-Roman British coins had them

(As usual with so many old and established things, there is argument over where the word “penny” comes from. Personally, we’ve always imagined that it’s an English diminutive of a Brythonic word—as it exists today in Welsh—“pen” = “head”, the idea being that coins had portrait heads on them. Certainly some pre-Roman British coins had them