Welcome, dear readers, as always, but, although the title of this posting might suggest taking cover during this time of worldwide illness, we persist in staying calm and remaining aboveground and writing more about subjects we—and, we hope you—find interesting.

We are about to teach The Hobbit again—although this time, not being sitting in a classroom with about 20 students, talking about what we’ve been reading, but somehow on-line, which is not very happy-making, as we really enjoy the always-intriguing reactions and questions which come from in-class discussion.

One observation from last term’s Hobbit reading has stuck with us: just how much of the dramatic action takes place underground—and there are also a number of like scenes, also very dramatic scenes, in The Lord of the Rings, as well.

We started adding them up and found, in The Hobbit:

- the world of the goblins under the Misty Mountains, where Gandalf kills the goblin king

and Bilbo finds the Ring and meets Gollum.

- in Mirkwood, the caves where the dwarves are kept prisoner by Thranduil, the king of the Forest Elves

until Bilbo frees them with his barrel-riding.

- the tunnels under the Lonely Mountain

where Bilbo and the dwarves must deal with Smaug.

In The Lord of the Rings, we find:

- Moria, with its mysterious western door,

the chamber of Mazarbul,

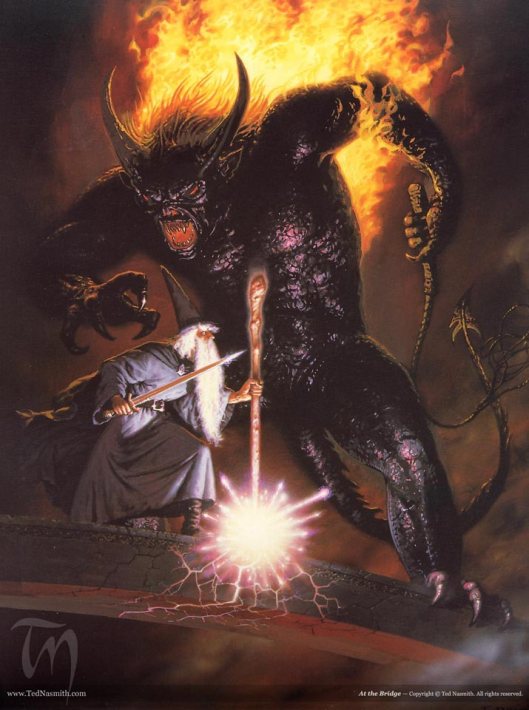

and the Balrog.

- the Pathways of the Dead

- and the area around Cirith Ungol, where Shelob has her lair.

Darkness, often narrow or treacherous places, full of fear–it might be supposed that Tolkien was a claustrophobe–

until you read this letter from 1940, in which he tells us of having made several visits—one in 1916—to some very famous caves (in this letter, he’s replying to someone who has asked about the caverns at Helm’s Deep):

“It may interest you to know that the passage was based upon the caves in Cheddar Gorge and was written just after I had revisited these in 1940 but was still coloured by my memory of them much early before they became so commercialized. I had been there during my honeymoon nearly 30 years before.” (Letters, 407)

Cheddar Gorge is in Somerset, in southwest England and is famous for its caves–

as well as its cheese.

We can deduce, then, that, in fact, JRRT was interested in caves and enjoyed them.

Scary caves go back farther in his life, however. We would suggest from childhood, when he read, one, and possibly two, stories by the once-popular Victorian children’s author, George MacDonald (1824-1905).

These books, The Princess and the Goblin (1872)

and The Princess and Curdy (1883),

as the titles suggest, have to do with the adventures of a princess, her friend, Curdy, and the swarms of goblins who live in a warren of caves below the palace. JRRT himself confessed, in a 1938 letter published in The Observer, to MacDonald’s influence:

“As for the rest of the tale it is…derived from (previously digested) epic, mythology, and fairy-story—not, however, Victorian in authorship, as a rule to which George Macdonald [sic] is the chief exception.”

(Letters, 31)

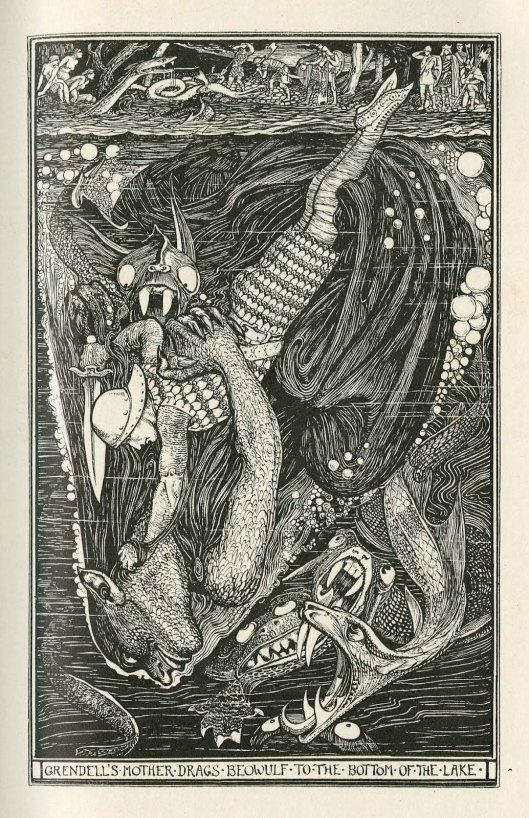

For later dark underground influences, we might add two spots in Beowulf: the lair of Grendel, which is not only underground, but underwater,

and the tumulus in which the (unnamed) dragon lives, the slaying of which causes the death of Beowulf.

Perhaps the most traumatic influence might be what was a traumatic experience for many more than JRRT.

In the summer of 1916, Second Lieutenant JRR Tolkien

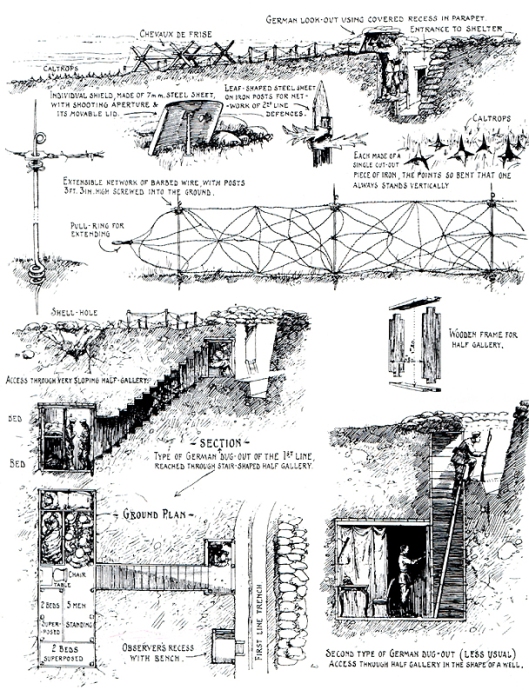

arrived at the Western Front, a subterranean land of trenches which cut up the world into endless crisscrosses of deep, often elaborate ditches with thickets of barbed wire in front of them,

protecting soldiers on both sides from the effects of heavy artillery

and machine guns,

in a crooked line which stretched for nearly 500 miles from Switzerland to the North Sea.

When he arrived, he was just in time to take part in a massive attack on a portion of the German lines in an assault which is now called the Battle of the Somme. This was a tremendous effort which cost the British on the first day alone a total of over 57,000 casualties.

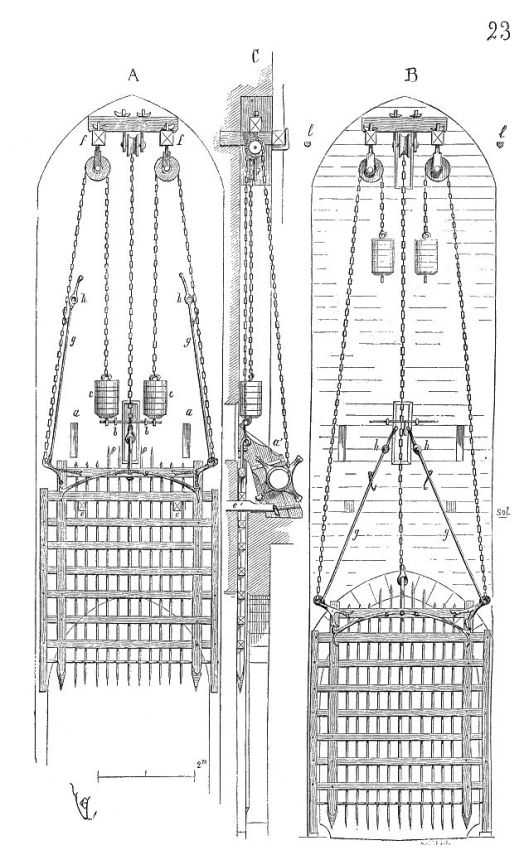

To soften up the enemy lines, the British had dug tunnels below them at various points,

filled them with explosives, called “mines”, and set them off just before the attacks.

Tolkien, as a signals officer—someone who dealt with communications after the first wave of attackers—

wouldn’t have been involved in mines or the initial assault, but would have followed behind, climbing into the enemy’s trenches to set up communication facilities after the attack had moved forward. He would certainly have seen these underground burrows, some of them extremely elaborate,

and perhaps childhood reading, the Cheddar gorge, and the experience of the Great War were all in his head when he began his first novel by placing his hero in a hole in the ground, then putting him back underground again and again?

Thanks, as ever, for reading. Stay well, dear readers, with

MTCIDC

CD

and finally two complete pictures by Ted Nasmith.

and finally two complete pictures by Ted Nasmith.

It interests us to see what will be the focus of the illustration. In JRRT’s complete description of the scene, we see the two figures juxtaposed when Gandalf challenges him:

It interests us to see what will be the focus of the illustration. In JRRT’s complete description of the scene, we see the two figures juxtaposed when Gandalf challenges him: