Welcome, readers, as always.

If you are among our excellent regulars, you know that we’re fascinated by history (one of us has taught it for years). One subset of our interest is “what ifs”, two of our favorite scifi/fantasy authors being Harry Turtledove and S.M. Stirling, who have written numerous books exploring all sorts of alternative places and times.

In this posting, we’d like to try a “what if” ourselves: what would happen to Minas Tirith if the Rohirrim and Aragorn had failed to arrive?

Walls collapsing under a rain of boulders, soldiers fleeing from the defenses, the main gate broken in by a giant battering ram—

how was this the place of which its creator had written:

“A strong citadel it was indeed, and not to be taken by a host of enemies, if there were any within that could hold weapons…” (The Return of the King, Book Five, Chapter 1, “Minas Tirith”)

In an earlier posting, we talked about Sauron’s attack on Minas Tirith

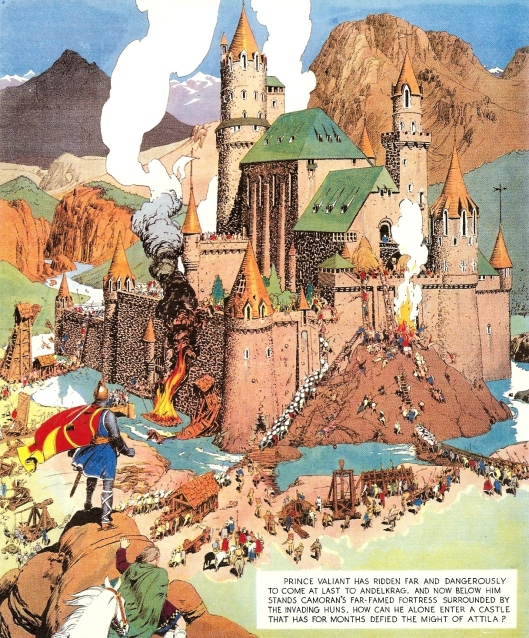

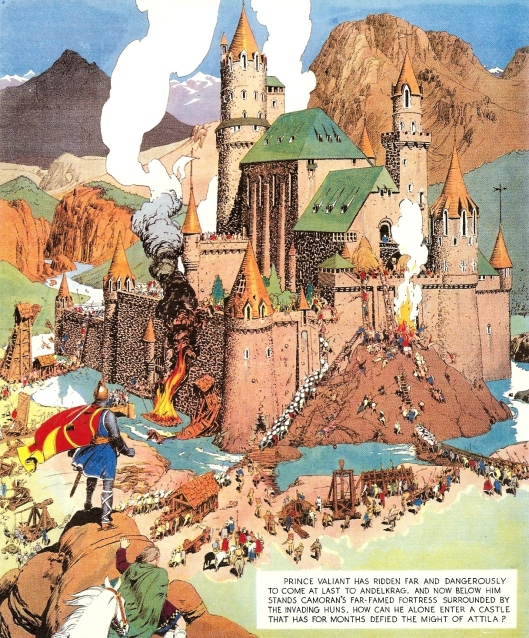

and even suggested that one inspiration might have been an episode of the comic strip Prince Valiant and the siege of Andelkrag by the Huns (published in May, 1939). (Footnote: there is a rumor that the writer/illustrator, Hal Foster, intended the Huns to equal the Nazis and therefore annoyed Hitler—a would-be Sauron to Saruman’s Mussolini, as we once also suggested?)

That castle is splendid, but not quite what one would have seen in the 5th century AD, when Attila led the Huns to invade central and western Europe. Andelkrag appears to be a very elaborate late-medieval castle, c.1400 or so, rather like the ones you might see in the Duc de Berry’s Tres Riches Heures (c.1412-16; 1440s; 1485-1489).

More likely, if Andelkrag had been a real fortress, it would have been a repurposed Roman army installation, like this at Caernarfon, called by the Romans, Segontium.

Such forts might then be converted into castles, as at Portchester

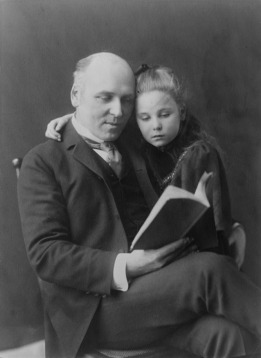

but that would hardly have provided the gallant medieval look which Foster gave his comic strip and which, in turn, came from the illustrations of people like Howard Pyle (1853-1911), in the previous generation (and which, we have previously argued, had a strong influence on what JRRT imagined his Middle-earth to look like).

We are told in one of the extra features in the extended film version of The Lord of the Rings that an inspiration for P. Jackson’s Minas Tirith

was the ancient island fort/religious site of Mont Saint Michel, on the western coast of France.

As you can see from the photo and the map, this isn’t just a fort, however, but a little fortified town, reminding us that Minas Tirith isn’t a castle, but a walled city, like the restored medieval town of Carcassonne, in southern France.

Like Mont St. Michel, Minas Tirith is built up a slope.

(This, by the way, is Tolkien’s first sketch.)

But, unlike Mont St. Michel and Carcassonne, it has not one wall, but many:

“For the fashion of Minas Tirith was such that it was built on seven levels, each delved into the hill, and about each was set a wall, and in each wall was a gate.”

Because the city was built on a series of levels, this would mean that each wall would overlook the next lower one, so that the defenders on the upper wall could rain down missiles on attackers below.

This is an ancient practice. The Bronze Age Greek city of Tiryns (yes, there is a bit of a similarity in the name, isn’t there?) is so constructed, for example, that its entryway forces attackers to move to the left, thereby potentially exposing an unshielded side, as well as undergoing a barrage of arrows and rocks from those on the wall above.

In the case of Minas Tirith, there is an added obstacle:

“But the gates were not set in a line: the Great Gate in the City Wall was at the east point of the circuit, but the next faced half south, and the third half north, and so to and fro upwards; so that the paved way that climbed towards the Citadel turned this way and then that across the face of the hill.”

Attackers, then, would not only be at the mercy of those above them, but would, should they break through one gate, be forced to zigzag back and forth as they fought their way upwards, taking more and more casualties as they advanced.

Added to this, at the lowest level, was the main wall:

“…of great height and marvellous thickness, built ere the power and craft of Numenor waned in exile; and its outward face was like to the Tower of Orthanc, hard and dark and smooth, unconquerable by steel or fire, unbreakable except by some convulsion that would rend the very earth on which it stood.” (The Return of the King, Book Five, Chapter 4, “The Siege of Gondor”)

Unlike so many fortresses—going back at least to Neolithic times—Minas Tirith had no moat. Not only does such a watery ditch slow down attackers by giving them one more puzzle to solve, but it also makes a standard siege practice, undermining, much more difficult. Basically, what undermining does is to hollow out an area underneath a wall and replace the original foundation with a flammable wooden one. Then the miners fill the hollow with burnables, torch them, and wait to see if the new wooden foundation collapses, bringing down the wall on top of it. You can see miners at work in this medieval manuscript illustration.

A wet moat would have forced the miners to dig much deeper, to avoid being flooded out.

For Minas Tirith, the nearest water source for a wet moat would have been the Anduin, some miles away, but dry moats were useful as well. This diorama of the final attack by the British at the siege of Badajoz in 1812 shows how effective such a thing might be. Although the besiegers have managed, through prolonged bombardment, to create a breach in the main wall, they have to struggle through the deep dry moat to reach it—and took large numbers of casualties in doing so.

Against all of these defenses, the head of the Nazgul, as Sauron’s general in the field, has the usual siege weapons: stone throwers, siege towers, even a massive battering ram. He also has a more subtle tool:

“But soon there were few left in Minas Tirith who had the heart to stand up and defy the hosts of Mordor. For yet another weapon, swifter than hunger, the Lord of the Dark Tower had: dread and despair.”

Even so, under the command of Gandalf, there was still resistance and we can imagine that that resistance would have persisted through all the circles, but the ultimate difficulty, which would have caused the fall of the city, had not the Rohirrim—and then Aragorn—come, was the lack of reserves.

Gondor was, at the time of the siege, in decline, as Pippin noticed when he and Gandalf arrived there:

“Yet it was in truth falling year by year into decay; and already it lacked half the men that could have dwelt at ease there.”

When reenforcements came from the south, they were “less than three thousands full told.”

When a city or castle is under siege, it needs not only a force to man its walls, but also a second force, to be sent quickly to any place where an enemy breakthrough is threatened. The force on the walls has two main jobs: 1. to keep the enemy at a distance with missile fire—or, failing that, to cut down the attacking force as it approaches the walls, trimming its numbers and thereby possibly demoralizing it; 2. to fend off the enemy if it actually manages to gain the walls. This illustration from the Prince Valiant Andelkrag siege provides a good image of this double job.

It might be possible, if the enemy made an assault upon a single point, to siphon off men from other parts of the defenses to act as a temporary second force, but, if the enemy attacks more than one place at the same time, this is not a safe thing to do. In the case of the assault on the first wall of Minas Tirith, the enemy commander seems to have had such numbers—and didn’t care in the least about his losses– that he could attack the entire wall:

“Ever since the middle night the great assault had gone on. The drums rolled. To the north and to the south company upon company of the enemy pressed to the walls. There came great beasts, like moving houses in the red and fitful light, the mumakil of the Harad dragging through the lanes amid the fires huge towers and engines. Yet their Captain cared not greatly what they did or how many might be slain: their purpose was only to test the strength of the defence and to keep the men of Gondor busy in many places.”

The weakest place in any strong wall is a gate and that knowledge has guided Sauron’s Captain:

“It was against the Gate that he would throw his heaviest weight. Very strong it might be, wrought of steel and iron, and guarded with towers and bastions of indomitable stone, yet it was the key, the weakest point in all that high and impenetrable wall.”

Thus, with everyone pinned in position by a general assault, and there being no other possible reserve, once the gate is down—but then a cock crows and there are horns and, well, you know what happens next.

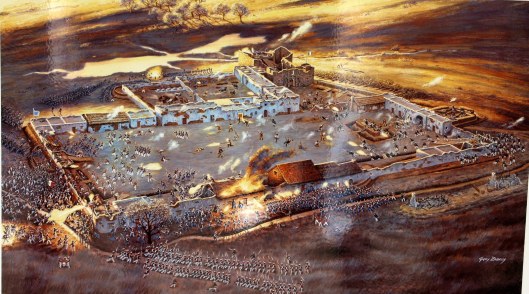

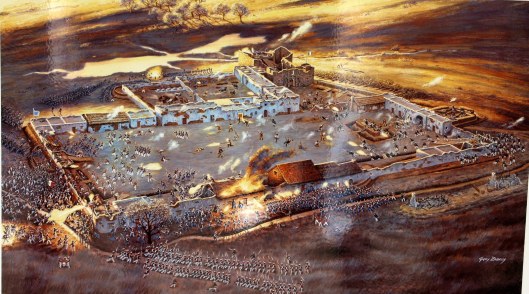

But, continuing our “what if”, we look to a different model, the Alamo, a ruined mission turned into a fortress in the so-called “Texas War for Independence” of 1835-36.

Within this mission, some 180plus defenders faced a Mexican army of several thousand, staving them off for a week-and-a-half before finally being overwhelmed by a series of nearly-simultaneous pre-dawn assaults from several directions at once.

The survivors drew back, still fighting, and made a series of last stands in the rooms of the surviving mission buildings, dying almost to a man because the Mexican general, Santa Anna, had declared that there would be no mercy for any survivors. (There were a handful of prisoners, however, perhaps including the famous American frontiersman, Davy Crockett, but under Santa Anna’s direction, they were then murdered.)

In our grim “what if”, the survivors of the outer wall, led in retreat by Gandalf, are gradually driven back, like the Alamo defenders, until they reach the Citadel—and then—but, can we go on? Are the Rohirrim and Aragorn simply delayed and then appear? Are there eagle-rescues, as in The Hobbit?

What do you think, dear readers?

And thanks, as ever, for reading!

MTCIDC

CD

PS

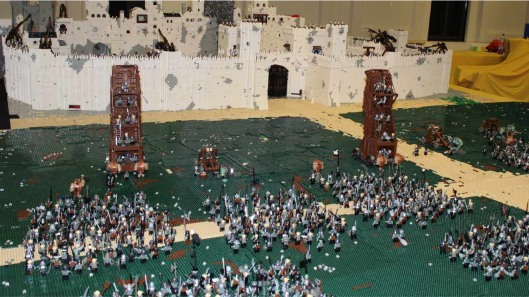

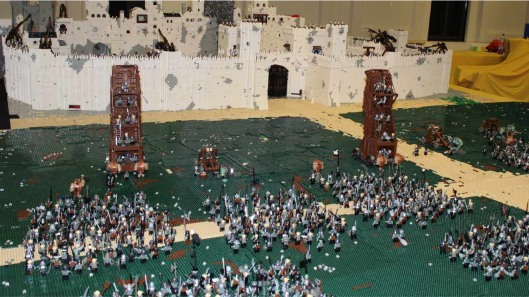

We saw this Lego attack on Minas Tirith and it was just too wonderful not to include!

PPS

As we were finishing this, we happened upon a really great website–

https://middleeartharchitectures.wordpress.com/ –wonderful visuals!