Welcome, as ever, dear readers.

We begin this posting with the Persians

and a post office.

This might seem a very odd pairing, but the inscription over the front of the 8th Avenue post office building in New York City (opened 1914) offers a connection.

This is only a part of the inscription, which reads, in full:

“Neither snow nor rain nor heat nor gloom of night stays these couriers from the swift completion of their appointed rounds.”

Persian? This doesn’t look like Persian. Now this looks like Persian—

This is one of a pair of inscriptions, called the “Ganjnameh Inscriptions”, “Ganjnameh” in Farsi meaning “Treasure Book”, the locals believing that, if you could read what was written on this pair,

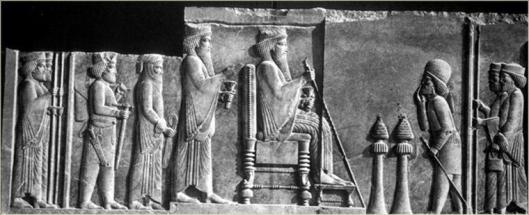

you would be given the instructions to find ancient buried treasure. Instead, they are about two Persian kings, Darius I (550-486BC—he’s the one sitting down) and his son, Xerxes I (c.518-465BC)

and, as good Zoroastrians, their patron god, Ahura Mazda.

Darius, often called “Darius the Great”, was an early and very ambitious Persian monarch, who extended his empire beyond its previous boundaries

and is known in Western history for being the king whose expeditionary force was defeated by the Athenians and their allies, the Plataeans, at the battle of Marathon, in 490BC.

The story of this monarch and that of his son, Xerxes, who led a second expedition against Greece 10 years later, are told in the Greek Heroodotus’ (c.484-c.425) Histories, a 9-book account of Greek relations with Asia Minor and particularly with Persia, seeking to explain, in part, why the two were at odds through several centuries.

As empire-builders, the Persians were easy rulers. They never had the troops to occupy their huge territories, once they had conquered them, but, instead, appointed a governor (satrap) and demanded two major items: troops, when required,

and taxes (always required).

To keep control of such a huge stretch of land, Darius and his successors maintained a direct route of communication from the western edge of Asia Minor to one of their capitals, at Susa. This route was called the “Royal Road” and stretched for nearly 1700 miles.

If it took months to walk the distance one way, but, with a long series of stations, each with fresh horses, a relay of messengers might travel the same distance in a week—and this is where that inscription on the post office comes in. Herodotus describes this road and its government service here:

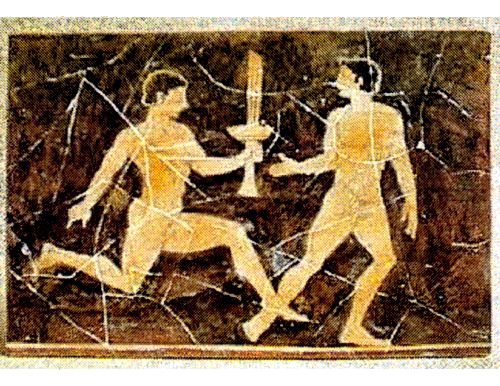

“Now there is nothing mortal that accomplishes a course more swiftly than do these messengers, by the Persians’ skillful contrivance. It is said that as many days as there are in the whole journey, so many are the men and horses that stand along the road, each horse and man at the interval of a day’s journey. These are stopped neither by snow nor rain nor heat nor darkness from accomplishing their appointed course with all speed. [2] The first rider delivers his charge to the second, the second to the third, and thence it passes on from hand to hand, even as in the Greek torch-bearers’ race in honor of Hephaestus. This riding-post is called in Persia, angareion.” (Herodotus, Histories, Book VIII, 98, from the 1920 Godley translation)

And here’s an illustration of what Herodotus suggests is a Greek parallel—

(If the message was by word of mouth, there could be a real danger of miscommunication—follow this LINK to such a danger by the wonderful Horrible Histories folk: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QKqkq4hGpgo )

You can see, then, that the builders of that New York post office, borrowing from (and adapting) Herodotus, wanted to suggest that the US Postal Service was as imposing (and as unbeatable?) as the Persian Imperial Post.

Long before the US Postal Service, however, the idea of something as speedy for government use as this was not lost upon the Romans.

The emperor Augustus, about the year 20BC, founded a Roman version of this service, called the cursus publicus, using the increasingly-elaborate Roman road network (ultimately 50,000 miles—80,000km–of paved roads).

We have a good description of this official service from a much later source, the Historia Arcana (“Secret History”) of Procopius (c.500-after c.565AD), a Byzantine court official at the time of the emperor Justinian (482-565AD):

“For the Roman Emperors of earlier times, by way of making provision that everything should be reported to them speedily and be subject to no delay, — such as the damage inflicted by the enemy upon each several country, whatever befell the cities in the course of civil conflict or of some unforeseen calamity, the acts of the magistrates and of all others in every part of the Roman Empire — and also, to the end that those who conveyed the annual taxes might reach the capital safely and without either delay or risk, had created a swift public post extending everywhere, in the following manner. 3 Within the distance included in each day’s journey for an unencumbered traveller2 they established stations, sometimes eight, sometimes less, but as a general thing not less than five. 4 And horses to the number of forty stood ready at each station. And grooms in proportion to the number of horses were detailed to all stations. 5 And always travelling with frequent changes of the horses, which were of the most approved breeds, those to whom this duty was assigned covered, on occasion, a ten-days’ journey in a single day…” (Procopius, Historia Arcana, xxx—translator, HB Dewing, 1935)

Remarkably, we can even trace the routes taken by couriers by using an extremely interesting piece of geographical charting, the so-called Tabula Peutingeriana, the”Peutinger Map”.

Named for Konrad Peutinger (1465-1547),

a scholar in whose hands it lay in the 16th century, it is 13th century copy of a map which may date all the way back to the time of Augustus himself. (If you’d like to read more about the map and theories of origin, here’s a LINK: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tabula_Peutingeriana )

The original was a 22-foot long scroll which, leaving out Britannia and Hispania, charts the thousands of miles of Roman roads. (See the LINK above for a roll-out of the whole map.)

The use of such a speedy service was not lost upon someone else, in a much later time. In the 3rd section of the “Prologue” to The Lord of the Rings, we see:

“The only real official in the Shire at this date was the Mayor of Michel Delving (or of the Shire)…the offices of Postmaster and First Shirriff were attached to the mayoralty, so that he managed both the Messenger Service and the Watch. These were the only Shire-services, and the Messengers were the most [sic] numerous, and much the busier of the two. By no means all Hobbits were lettered, but those who were wrote constantly to all their friends (and a selection of their relations) who lived further off than an afternoon’s walk.” (The Lord of the Rings, Prologue, Section 3—the word “sic” is inserted in brackets above because there’s a grammatical error in the text here. JRRT names only two groups, the Messenger Service and the Watch, which means that one should use the comparative form of “much/many”, which is “more”, here, instead of the superlative “most”, which would be used for more than two groups.)

This establishes a postal service in the Shire—but what about the speedy part? We turn to the next-to-the-last chapter of The Return of the King, “The Scouring of the Shire”, and listen to Robin Smallburrow speaking with Sam:

“We aren’t allowed to send by it now, but they use the old Quick Post service, and keep special runners at different points.” (The Return of the King, Book Six, Chapter 8, “The Scouring of the Shire”)

And, as this posting was entitled “A Quick Post”, we’ll end here, saying, as always, thanks for reading and MTCIDC,

CD

ps

That post office motto turns up in a comic form (with missing letters), more or less, in Terry Pratchett’s Going Postal (2004),

where, on the central post office in Ankh-Morpork, may be read the inscription: “Neither rain nor snow nor glo m of ni t can stay these mes sengers abo t their duty”.

We recommend not only this (one of our favorite Pratchett novels), but also recommend the film adaptation, which really captures much of the feel of the book.