Welcome, dear readers, as ever.

For me, one of the many pleasures of The Lord of the Rings is its landscape—not just that map which caused Tolkien so many hours of worry, but all of the places on it with all of their names, each clearly made with care and attention to linguistic detail, beginning with the creation of the Shire and all it contains, but moving beyond it to encompass the whole of Middle-earth. As he explained in a letter to Rayner Unwin:

“Yet actually in an imaginary country and period, as this one, coherently made, the nomenclature is a more important element than in an ‘historical’ novel.” (Letter to Rayner Unwin, 3 July, 1956, Letters, 250)

And yet, for all of that care, Tolkien the story-teller never draws attention to that naming. As in any country, especially a very old one, as the Shire and, in turn, Middle-earth, are meant to be, the names are just that and, like the land itself, they have become worn-down natural features. As JRRT himself writes in that same letter to Rayner Unwin:

“Actually the Shire Map plays a very small part in the narrative, and most of its purpose is a descriptive build-up.”

It’s always been a disappointment, then, to me that the main ancient telling of the story of Jason and the Golden Fleece

fell into the hands of a man who, unlike JRRT, was not the poet to tell such a romantic story, but was, instead, Apollonius of Rhodes (first half 3rd Century BC),

whose narrative, The Argonautica,

(This is a very early printed version, from 1521.)

is laid out in 4 books: two to get Jason to his goal, Colchis,

one for a romance with Medea, the daughter of the nasty local king,

(shown here in a later murderous moment)

and one for grabbing the Fleece (and Medea)

and heading for home on a trip which includes, besides touring the Danube valley, carrying their ship, the Argo, across a desert.

This is a story with a typical folktale beginning: Pelias, half-brother of Aeson, has overthrown Aeson and taken over the throne of Iolcus. Now, Aeson’s son, Jason, is coming back to Iolcus, and uncle Pelias has been warned by an oracle to beware of a man wearing one sandal. Jason, in fact, has just lost one of his, when he carried an old lady across a stream.

(Because there is an old folktale under this, that’s not really an old lady, it’s the goddess, Hera, in disguise, to test Jason—he obviously passes and she will help him throughout the rest of the story.)

Pelias, to get rid of Jason, gives him a quest: bring back the Golden Fleece from the far side of the world. (Without going into more detail, suffice it to say that the Fleece was on a flying escape ram piloted by Phrixus, along with his sister, Helle, who are—what else? escaping the plots of an evil stepmother.) This is meant to be an impossible task and Pelias has every expectation that Jason will not return, with or without the Fleece.

(This is the elaborate back of a 2nd century AD Roman mirror.)

What has always frustrated me about this telling is that, potentially, it’s packed with interesting adventures—harpies,

mobile cliffs,

Amazons,

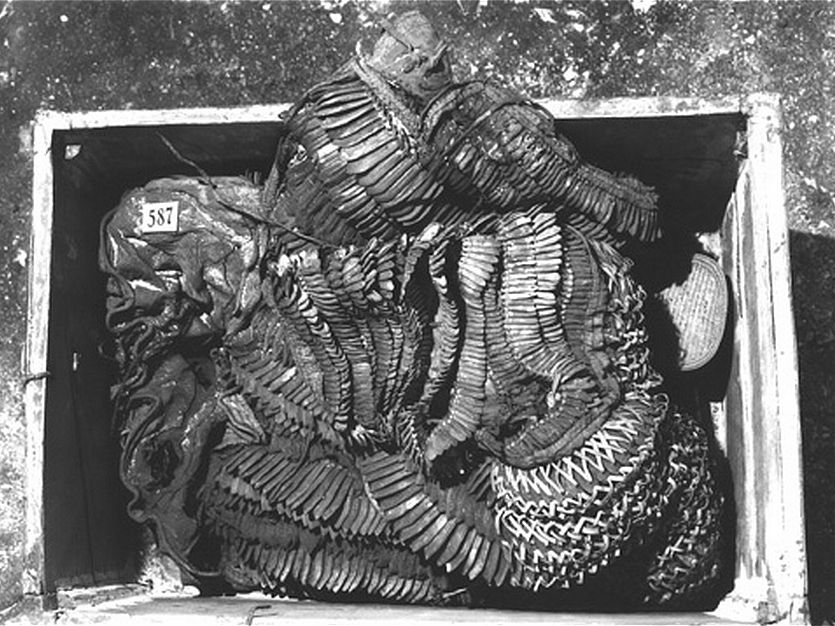

not to mention the fact that the Fleece itself is guarded by a sleepless dragon.

But, although he writes about these things, what really seems to interest Apollonius aren’t such epic challenges, but the origins of place names along Jason’s route. This toponymy—the study of which comes, appropriately, from two Greek words, topos, “place” and onoma, “name”—then turns the narrative at times into a kind of geographic/mythological check list and so we spend what sometimes feels like half the trip forced to listen not to another Homer, but to a rather pedantic tour guide.

There are those scholars who have, in recent years, argued that Apollonius never intends to be another Homer and, coming from a later age of Greek literature (the so-called Hellenistic Era), he has different goals and, while this could certainly be true, for me, an epic story like this should be epic, not microscopic.

Tolkien, in contrast, although he spent so much time creating those place names and attaching them to geographical features, still sees them as simply part of the “build-up”, that is, the physical context in which his characters move.

I want to emphasize, however, that, although Apollonius may overfocus on toponymy and sometimes weigh his story down with it, this isn’t to argue that toponymy in itself is a dull subject: on the contrary, it’s a very interesting subject and Tolkien was certainly one of those interested, once writing to his son, Christopher, that “I like history, and am moved by it, but its finest moments for me are those in which it throws light on words and names!” (letter to Christopher Tolkien, 21 February, 1958, Letters, 264)

This isn’t surprising as JRRT, with his keen ear and eye for language, lived in an England whose very history could be traced in broad terms in the strata of its toponymy. Traces of its Celtic settlers barely survive, but some place and river names, like the Avon, reflect the language of the pre-Roman inhabitants (afon meaning “river”). Roman occupation in all its might appears in every place with “chester/cester/caster” as an ending, from Latin castra, “military camp”. The Anglo-Saxons are everywhere with endings like -ton (old tun, “enclosure”) and -hurst (hurst, “clearing”). Though there are many fewer Norman names, we can still see traces of their take-over in a compound like Ashby-de-la-Zouch, which I mentioned in my last as the scene of the great tournament in Scott’s Ivanhoe. This name even adds a Viking element, by, “settlement”, to an Anglo-Saxon ash, “ash tree” together with the family name of the later Norman owners, the La Zouche family, who owned a nearby castle in the 13th century. Putting all of these elements together gives us hundreds of years of medieval history, while also making a bold political statement: “the settlement among the ash trees” it begins—and then, as if in large letters on a billboard on the way into the village—”NOW OWNED BY THE LA ZOUCHE FAMILY”.

(Just in case you don’t have an ash tree in your mental topography)

How little we would know about that place if it had simply been called “Ash” and I wonder what the Argonautica might have been like if, like Tolkien, Apollonius could have loved his toponymic trees, but let them stand as only a part of his narrative forest?

Thanks, as always, for reading,

Stay well,

Wherever you are, look at a place name and wonder,

And, as ever, know that there’s

MTCIDC

O

PS

With this, essay #363, doubtfulsea.com is now beginning its 7th year. Years ago, a fortune teller (yes—a real one, a member of the really interesting Romani culture ), told me that my lucky number was 7, so I’m looking forward to another year full of essays about everything from epic to adventure to the occasional film review (I have the Jackson film of Mortal Engines first on my list) to whatever catches my interest and, if you’re a regular reader, you know that this means almost anything.