Tags

banner, Captain Souter, color, Dol Amroth, ensign, Eye of Sauron, First Afghan War, flag, George Washington, Revolutionary War, Rohirrim, saltire, standard, The Lord of the Rings, The Song of Solomon, Tolkien, Trooping of the Colour, White Hand of Saruman, white horse of Hannover, White Tree of Gondor, WWI, WWII

Welcome, dear readers, as ever.

Our title comes from the Hebrew Bible, in the book entitled The Song of Solomon, Chapter 6, verses 4 and 10, where the speaker’s beloved’s beauty is likened to an army with banners. Growing up, we always wondered about that word “terrible”. We didn’t see why someone’s good looks could be frightening, but we could certainly see how an army with its flags could be scary.

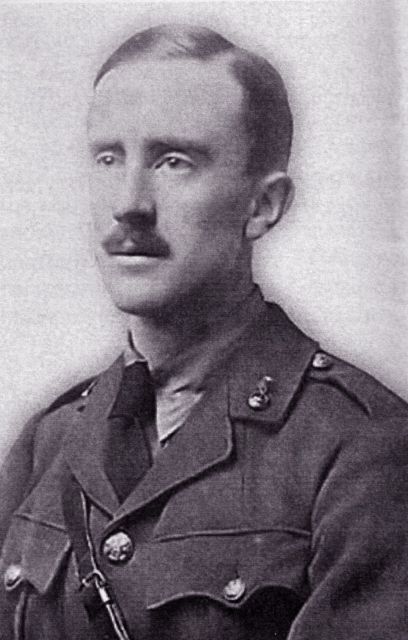

On the subject of banners, recently, we’ve been writing about 2nd Lieutenant JRR Tolkien.

In an earlier posting, in fact, we mentioned that that rank of 2nd Lieutenant was a replacement for the earlier rank of “ensign”. “Lieutenant” is just the English version of a French compound for “place-holder” (lieu + tenant), in this case meaning the person who will step into the captain’s shoes if necessary. Instead of a compound with its implication of replacement, “ensign” is actually a job description. An “ensign” is a flag (a “color”, if infantry, “standard”, if cavalry) and an “ensign” is also the person who carried it.

By 1916, when Tolkien became a 2nd Lieutenant, colors were no longer carried in battle, but only on parade, as this early-20th-century illustration demonstrates—

and is still the case for the famous “Trooping of the Colour” for the Queen of England’s birthday parade, where her splendid footguards march with one of their colo(u)rs.

This is clearly all about show, now, but, once upon a time, colors—and their ensigns—had an important role in warfare. Earlier colors were much bigger—in the 18th century, they were 6 feet by 6 feet square (1.82 metres by 1.82).

And here are some modern reenactors to help you to see just how big that really is.

The reasons for such a size (on a 9-foot pole, or “pike”—that’s 2.74m) are:

- units in earlier times (pre-late-19th-century, more or less) fought in long lines and, if you put the colors in the middle, everyone in a unit had a kind of fixed point to help them know where they—and their unit—were

- as well, earlier firearms, which used black powder, put out enormous clouds of (white) smoke—

If colors were big and tall, they could still be made out in the midst of those clouds.

They could also act as a rallying point. When lines came apart and the order was Charge! (Or when things were falling apart and the call was for Retreat!)

In time, colors came to be thought of as almost the physical representative of the spirit of a unit and being called upon to surrender them was looked upon as the worst disgrace. This portrait of George Washington would have been thought particularly nasty by his British and German enemies because all around him are their colors, captured in two battles, Trenton and Princeton. (His own headquarters flag—13 stars in a circle on a blue background—is in the upper right of the picture.)

To escape surrendering their colors, soldiers would strip them from the poles/pikes and hide them in their clothes or, in real desperation, burn them, as the French did in 1760 when forced to surrender to the British at Montreal, in Canada (then New France).

In earlier centuries, before gunpowder came to dominate battlefields, colors were already used as rallying points,

but also, in the days before uniforms, colors—big or little—indicated who was fighting. If you saw a figure bearing a flag with a white, angled cross (a “saltire” in heraldic terms) on a blue field (background), for example, you knew that the King of Scotland was on the battlefield.

Thus, although 2nd Lieutenant Tolkien would no longer carry one of his unit’s colors into battle, as previous ensigns had, he would have known the importance of their role—and especially of the role of what they carried, which is why, for example, we see that, when it comes to battle in Middie-earth, nearly everyone seems to have a distinctive flag:

- the Rohirrim have their running horse

(which we think JRRT may have borrowed either from the chalk cutting known as the “White Horse of Uffington”

or possibly from an emblem long-related to the British monarchy, the white horse of Hannover—as we can see on this 18th-century grenadier cap).

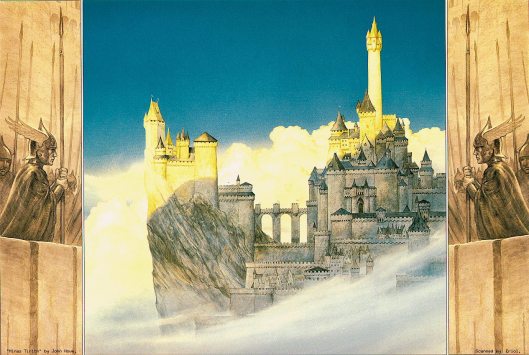

- Gondor has its tree and stars

- and, when Aragorn marches out of Minas Tirith,

it’s under his version of that banner–

which also boldly states his claim to be the rightful king—without actually coming out and saying it—compare the two banners–

- and the Prince of Dol Amroth has his flag, with “his token of the Ship and the Silver Swan” (The Return of the King, Book Five, Chapter 1, “Minas Tirith”).

As for their opponents, we see Saruman’s white hand on armor,

so we can presume, we think, that any banners carried would bear the same insignia and the same is true for Sauron’s orcs, which would have borne the lidless eye.

(We might also note that Southrons in the service of Mordor appear to carry red banners—as Gollum reports to Frodo and Sam in The Two Towers, Book Four, Chapter 3, “The Black Gate is Closed”.)

All of which made us wonder if Solomon would have been so eager to describe his beloved as he did if the army he saw looked like this?

As ever, thanks for reading and

MTCIDC

CD

ps

In an odd but fortunate use of a color, in 1842, during the First Afghan War, a Captain Souter was saved because he had hidden one of his regiment’s colors by wrapping it around his waist. As the last members of his unit fell around him, his Afghan opponents saw what they believed to be a fancy waistcoat/vest and took him prisoner, hoping for a rich ransom.

Her armor is full plate, which, in our world, is later medieval. As for the helmet, it somewhat resembles a visored sallet, but only vaguely.

Her armor is full plate, which, in our world, is later medieval. As for the helmet, it somewhat resembles a visored sallet, but only vaguely.