Tags

bokor, Bran, Circe, Cleromancy, Dol Guldur, Dracula, King Saul, Necromancer, necromancy, Odyssey, Oneiromancy, Robert Southey, Rockapella, Romania, Samuel, Sauron, Teiresias, The Hobbit, The Lord of the Rings, The Walking Dead, Tolkien, Zombie, Zombie Jamboree

“It was a Zombie Jamboree,

Took place in the New York Cemetery.

It was a Zombie Jamboree,

Took place in the New York Cemetery.

Zombies from all parts of the island

Some of them were great calypsonians.

Since the season was carnival,

They got together in bacchanal

HUH! And they were singing:

Back to back, belly to belly

Well I don’t give a damn

‘Cause I’m stone dead already!

Back to back, belly to belly

It’s a Zombie Jamboree.” (Conrad Eugene Mauge, Jr., c.1953)

What in the world are we doing, dear readers? Are we about to launch into a posting about The Walking Dead?

Well, no. Unless we mean the “walking-again dead”, which we do. And how did we get here?

It all began with our last two postings, on see-ers—that is, seers–and so many different ways of telling the future, like oneiromancy (dream interpretation) and cleromancy (using numbers), but, among them, we think the most sinister is necromancy—and this brought it to mind:

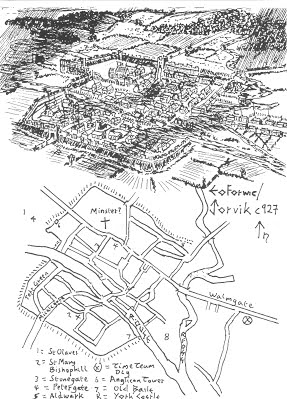

“Some here will remember that many years ago I myself dared to pass the doors of the Necromancer in Dol Guldur, and secretly explored his ways and found thus our fears were true: he was none other than Sauron, our Enemy of old, at length taking shape and power again.” (The Fellowship of the Ring, Book Two, Chapter 2, “The Council of Elrond”)

This is Gandalf recounting his adventure in Isengard. What he’s relating here happened somewhat before the action in The Hobbit, followed by the White Council’s attack on Dol Guldur (“The Hill of Dark Sorcery”), in the southern part of Mirkwood.

That was parallel in time to the travels of Bilbo and the dwarves towards the Lonely Mountain.

Here’s how John Howe thought Dol Guldur might have looked.

And here’s how it appears in The Hobbit films

although why it’s a ruin is unclear—Gandalf has said above that Sauron is “taking shape and power again”, and so we would imagine that, just as he’s reconstituting himself, there’s been a rebuilding campaign at his headquarters in the forest. So, rather like Howe, we see the place as more imposing, perhaps like Bran castle, in Romania, which is advertised as “Dracula’s castle” in tourist literature.

Just as cleromancy means “telling the future by lots” (that is, by casting lots—think of throwing dice–giving you a supposed “random” result) and oneiromancy means “telling the future by dreams”, so a necromancer uses the dead to find things out, suggesting something really horrible about someone with that title.

The process of questioning the dead goes back a long way in western literature. In the Odyssey, Circe,

who once turned part of Odysseus’ crew into pigs, tells him that, before he can go home, he must sail south, to the Otherworld, to consult Teiresias, who is a seer (see our last two postings for more on people like this)

for current information about his home on Ithaca and for coaching about his future behavior. To deal with the dead, Circe tells Odysseus in detail how to make a kind of drink offering of animal blood in a pit.

Then, because all of the dead will be drawn to the blood (we’re back to Dracula here, aren’t we?), he is to draw his sword and stand over the pit, only allowing those he would question to sip the blood.

But why would a sword threaten ghosts? one might ask. We think that the answer is that it’s iron and iron, in folklore, is a protection against evil magic. Odysseus has used his sword earlier to threaten Circe, who is a very powerful sorceress. See this LINK for more.

Odysseus is successful in his quest, but King Saul, in First Samuel, in the Hebrew Bible, who has already banished necromancers and magicians from his kingdom, is not. Saul is anxious about a battle to come and, when he is not answered via prayers and cleromancy about its outcome, he consults a kind of witch, who may (scholars argue over this) produce the spirit of the prophet Samuel.

When Samuel appears, his response to Saul is not what Saul had hoped for. Instead, Samuel scolds Saul and gives him a fortune-telling he’d rather not hear, that he will lose the battle, his army, and his life the next day, all of which comes true.

Saul had hoped that he could make Samuel do his bidding, which was less than successful, but what if one might make the dead one’s slaves? This is where our opening comes in. The tradition of zombies is complex, including the word itself. At the moment, the earliest reference to the word in English is found in 1819, in volume 3 of the poet, Robert Southey’s (1774-1843),

History of Brazil, Part the Third, page 24:

They were under the government of an elective Chief, who was chosen for his justice as well as his valour, and held the office for life : all men of experience and good repute had access to him as counsellors : he was obeyed with perfect loyalty; and it is said that no conspiracies or struggles for power had ever been known among them. Perhaps a feeling of religion contributed to this obedience ; for Zombi, the title whereby he was called, is the name for the Deity, in the Angolan tongue.”

The subsequent history of zombies is complex, but a recurrent theme is that they are the dead, brought back to serve the living, usually by an evil magician, called a bokor. Among the possible tasks for such a slave is telling the future, thus making a bokor a necromancer, like Sauron.

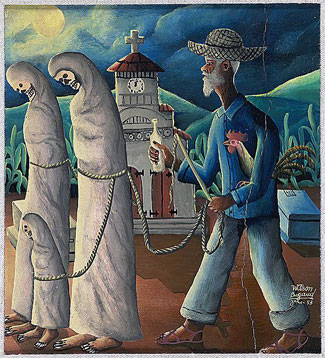

We’ve done an extensive image search under “zombie” and the weirdest things turn up, none of which we would put into a posting, so this is the best we can do.

If, however, this is the best a bokor can manage, we can’t imagine what news of the future one of these zombies might possibly give Sauron—and it’s no wonder that he loses the Ring.

But thanks for reading!

And

MTCIDC

CD

ps

If you’d like to see “Zombie Jamboree” performed, here’s a LINK to our favorite version, by Rockapella.