“But the Ring was lost. It fell into the Great River, Anduin, and vanished. For Isildur was marching north along the east banks of the River, and near the Gladden Fields he was waylaid by the Orcs of the Mountains, and almost all his folk were slain.” (The Fellowship of the Ring, Book One, Chapter 2, “The Shadow of the Past”)

(Here’s a map to help you to orient yourself.)

Welcome, as ever, dear readers. Gandalf is about to tell Frodo—and us–about what, in the orthography of the Pooh books, might be written as What Happened Next (although that “next” is relative, there being over 2400 years between the Ring’s loss and Deagol’s finding it, about which Gandalf is going to speak). As interesting and important as his explanation is, however, in this post we are going to stop right here, at that word “waylaid”, meaning “ambushed”.

In Unfinished Tales, edited by Christopher Tolkien, there is much more detail about this event, beginning with:

“To their right the Forest loomed above them at the top of steep slopes running down to their path, below which the descent into the valley-bottom was gentler.”

Suddenly as the sun plunged into cloud they heard the hideous cries of Orcs, and saw them issuing from the Forest and moving down the slopes, yelling their war-cries.” (Unfinished Tales, 284 in the Ballentine paperback edition)

Even though it’s clear from Gandalf’s narrative that this part of the story of the Ring was not common knowledge (“And there in the dark pools amid the Gladden Fields…the Ring passed out of knowledge and legend, and even so much of its history is known now to only a few…” he says to Frodo), this ambush was a major moment in the history of Middle-earth. Thinking about it and where Isildur and his men were waylaid—a body of water to one side, steep, wooded ground to the other—immediately reminded us of two important ambushes from the distant past of our Middle-earth.

Hannibal, the great Carthaginian general, in order to force Rome to break off its second war with his country, had invaded Italy, crossing the Alps with his army—and one surviving elephant—in 218BC.

Having defeated one Roman army at the Trebbia in the same year, Hannibal was the target of new Roman efforts the next (217BC). Unfortunately for the Romans, Hannibal was a more skillful general than his opponent, Gaius Flaminius, and lured the Romans into a terrible trap.

Hannibal very ostentatiously pitched his camp at the far end of the northern shore of Lake Trasimene, but concealed his troops in the wooded hills above the road. The Romans, believing that they had a good chance of pinning the usually wily Carthaginian general, marched along the lake road, making for the camp. When it was clear that the Romans had so far advanced that their rear guard was under the shadow of the hills, Hannibal gave the signal, the trap was closed at both ends, and the battle began with the unsuspecting Romans slammed into from three directions at once.

As the fourth direction was the lake, many Romans were driven into it and were drowned,

their general, Flaminius was killed, and only about a third of his army managed to escape, mainly by pushing through the troops in front of Hannibal’s camp.

Although there was no river or lake in our second ancient ambush, there was a huge bog—in northwestern Germany, in 9AD.

Since the days of Julius Caesar in the last century BC, the Romans had pushed to extend their control eastward from their possessions in Gaul. Celtic Gaul, with its towns and its centuries of contact with Greek traders and trade goods, was relatively easy to conquer (reading Caesar’s account of his campaigns in Gaul, “relatively” is definitely a relative word, however). Germania, heavily wooded, with no large settlements, only farms here and there in clearings, and bands of tribal warriors

was much less promising, but the Romans had made progress since Augustus had become emperor (30BC)—or thought that they had.

In their earlier struggles, they had defeated the leader, Segimer, (Segimerus, in Latin) of a powerful western tribe, the Cherusci, and, according to Roman practice, had forced him to turn over several of his children as hostages. One of these, whom we know as Arminius (we don’t know what his family called him, just what the Romans did), given high status and military training, seemed to be a promising addition to the Romanification of German lands. Seemed, however, is the correct verb as, once he returned to his homeland as a Roman officer, he used his family’s connections to create a league of tribes for the purpose of driving his adopted people from his native country.

His plan fell into place when he tricked the local Roman commander, P. Quinctilius Varus, into believing that there was a local uprising and that he should march to suppress it as soon as possible. Varus took the major part of the Roman garrison—at least 20,000 men—on local paths (no paved Roman roads in this part of the world) deep into the forests

where thousands of warriors were waiting, many on a wooded hillside to the south of the narrow Roman march route.

In open country, when Romans were attacked, their training allowed them to snap into defensive formations which, if necessary, could protect them from any direction.

With their soldiers strung out for miles along a forest path, a hillside to one side, a swamp to the other, their training was of little help, however,

and the majority of the Romans—nearly all 20,000, it is thought—were killed or taken prisoner, to be sold as slaves or perhaps sacrificed as thank-offerings.

After this disaster, the Romans never seriously attempted to march deeper into Germanic lands, but contented themselves with constructing a long defensive line to their south, the so-called Limes Germanicus (“German Frontier”—literally, “German threshold”).

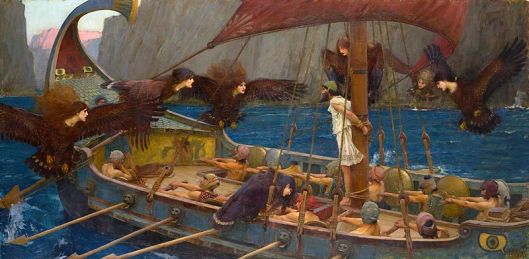

We’ve mentioned Isildur’s fatal ambush, from long before The Lord of the Rings, but there is another ambush within the text itself: the attack by Faramir’s men upon a unit of Southrons, in the chapter entitled “Of Herbs and Stewed Rabbit”. It’s where Sam gets to see his “oliphaunt”, of course,

but, for us, the more moving moment is something else which Sam sees:

“Then suddenly straight over the rim of their sheltering bank, a man fell, crashing through the slender trees, nearly on top of them. He came to rest in the fern a few feet away, face downward, green arrow-feathers sticking from his neck below a golden collar…It was Sam’s first view of a battle of Men against Men, and he did not like it much. He was glad that he could not see the dead face. He wondered what the man’s name was and where he came from; and if he was really evil of heart, or what lies or threats had led him on the long march from his home; and if he would not really rather have stayed there in peace…” (The Two Towers, Book Four, Chapter 4, “Of Herbs and Stewed Rabbit”)

As we linked the ambush at the Gladden Fields to those at Lake Trasimene and the Teutoburg Forest, so we link this, presumed to be a sad response to what happened in Germany in 9AD, to Sam’s reaction.

It’s what’s called a cenotaph, Greek for “empty tomb”. In the Greco-Roman world, everyone who was not buried properly would suffer in the afterlife, and so, even if it were only a token, like Antigone scattering dust over her dead brother in Sophocles’ play, the dead had to be given some kind of burial. The inscription says that Publius Caelius erected this stone to his brother, Marcus Caelius, a senior officer in the 18th Legion, from Bologna in northern Italy, who, at 53-and-a-half, died in the “Varian War”, meaning what was hardly a war, but more like a massacre, in the Teutoburg Forest.

Sam’s Southron was just an anonymous soldier in an anonymous unit. Marcus Caelius was a career military man, high up in a well-known unit. Still, we wonder, like Sam, what led him from his home and whether he would like to have stayed there in peace.

As always, thanks for reading.

Stay well

And

MTCIDC

CD