Welcome, dear readers, as always.

When I was little, I was always a bit disappointed by the end of the film of The Wizard of Oz.

First, Dorothy had so proved herself: a little girl with some picturesque friends

had defeated that really terrifying woman with her green face

and her flying monkeys,

not to mention those men with the green faces and the catchy tune,

but, instead of finding her own way home, there’s the Wizard, now revealed as a fake, with a balloon.

When that doesn’t work, it turns out that her sparkly footwear

could have taken her there at any time, if only she’d known—and the person who tells her this, Glinda, the Good Witch of the North, herself had known that fact all the time.

Of course, if Glinda had told Dorothy that detail when she removed the slippers from the feet of the recently-deceased Wicked Witch of the East,

it would have been a very short film, but, as the text of The Wonderful Wizard of Oz (1900),

makes clear, there would have been other consequences if Dorothy had immediately tapped those heels together:

“Your Silver Shoes will carry you over the desert,” replied Glinda. “If you had known their power you could have gone back to your Aunt Em the very first day you came to this country.”

“But then I should not have had my wonderful brains!” cried the Scarecrow, “I might have passed my whole life in the farmer’s cornfield.”

“And I should not have had my lovely heart,” said the Tin Woodman. “I might have stood and rusted in the forest till the end of the world.”

“And I should have lived a coward forever,” declared the Lion, “and no beast in all the forest would have had a good word to say to me.”

“This is all true,” said Dorothy, ” and I am glad I was of use to these good friends. But now that each of them has had what he most desired, and each is happy in having a kingdom to rule beside, I think I should like to go back to Kansas.” (The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, 257)

Reading the original as a grown-up, I realized that the script writers for the film, attempting to simplify things, had actually confused the reason why Dorothy initially wasn’t made aware, inadvertently leaving the audience with the idea that the Good Witch of the North wasn’t such a good witch, after all.

In the novel, when Dorothy’s house, whirled by the cyclone,

landed on what we would find out was the Wicked Witch of the East, the Good Witch of the North (later called “Locasta” by the author) had appeared,

but this was not Glinda, who was, in fact, the Good Witch of the South, and Glinda, with her news about the shoes, only turns up in the next-to-last chapter of the story.

If you’ve only seen the film or haven’t read the book, here’s a map of Oz to make this a little clearer.

It seems that it was known among the Munchkins (slaves of the Wicked Witch of the East until her unfortunate collision with falling real estate) that there was something magical about the shoes, but not exactly what that was and so, when the Good Witch of the North, aka Locasta, gave Dorothy the slippers, she did so without herself fully understanding their potential. (If you don’t have your own copy with the original Denslow illustrations, here’s one for you: https://archive.org/details/wond_wiz_oz )

Balloon or shoes, I was disappointed, but the image of the balloon floating off without Dorothy

finally landed when I first learned the term deus ex machina, literally “a god from out of a device”. This is now used to mean an ending which looks (at least faintly) contrived, but, originally, it was a theatrical term from Greco-Roman theatre.

Imagine that you’re in the audience at a performance of, for example, Euripides’ (c480-c408BC)

tragedy, Orestes. This is a crazy play (here’s a modern translation, in case you’d like to see for yourself: https://www.poetryintranslation.com/PITBR/Greek/Orestes.php ), which seems about to end with the title character, Orestes, along with his sister, Electra, and his BF, Pylades, trapped in a palace which they threaten to burn down—oh, and they have a hostage, Orestes’ cousin, Hermione, only daughter of Orestes’ uncle, Menelaus, and his aunt, Helen.

Then, when it looks like things are just impossible, the god Apollo

appears—literally—out of the air. He stops the action dead and snips all of the knots which the plot had twisted itself into.

Apollo appeared thanks to a device—in Greek, mekane (MAY-kahn-AY)–we use the Latin form, machina (MAH-keen-ah), which, if the audience closed its eyes a little, allowed a divinity to seem to float into view over the stage.

Thus, even an ancient Greek play can have, in Apollo, a deus ex machina, both in the ancient and modern senses, and perhaps, when I was little, the balloon and the slippers both seemed too much like such an artificial resolution to be satisfying.

Such a device, however, turns up all the time in fiction, mostly when writers are having trouble resolving plot problems, or finding closure. There are those who think, for example, that the death of Daenerys in the finale of A Game of Thrones was such.

(If you’d like to see someone’s view of recent film deus ex machinas, see: https://whatculture.com/film/10-movies-that-relied-on-deus-ex-machina )

For me, the combination of being airborne and deus ex machina brought up the possibility that we may be seeing the use of one in The Hobbit

and The Lord of the Rings,

in the form of the eagles.

These appear, after all, just as a deus ex machina would: when the dramatic situation seems especially unsolvable, but are they really such weaknesses in the narrative or the author’s art?

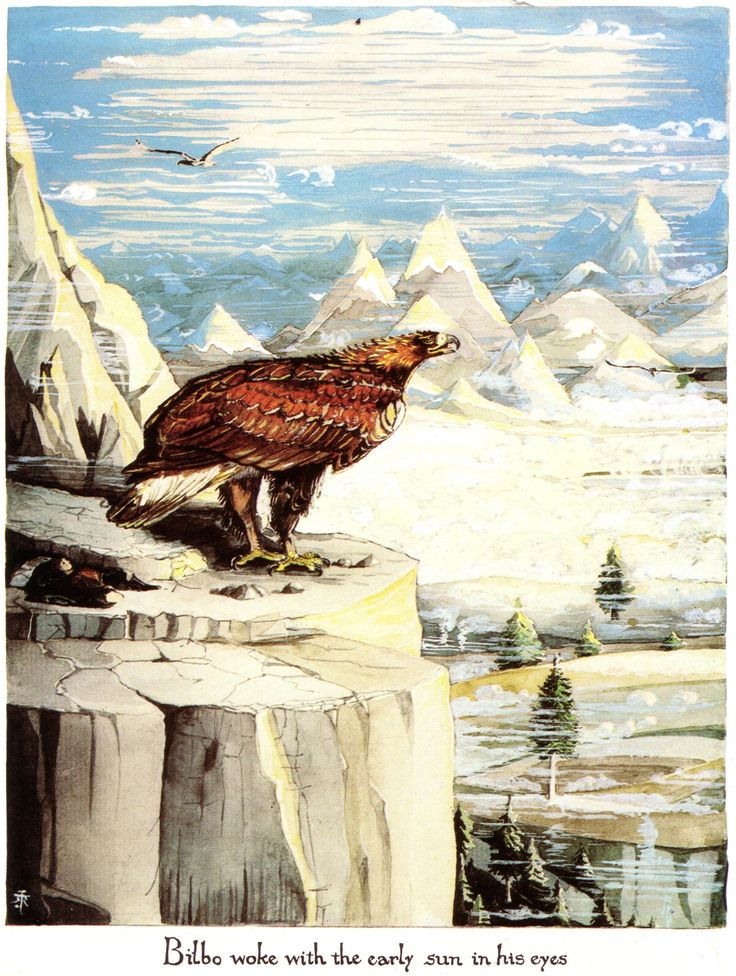

We first see them in Chapter 6 of The Hobbit, “Out of the Frying-Pan into the Fire”, where they rescue the treed dwarves, Bilbo, and Gandalf from the attack of the Wargs, the more-than-wolves.

The justification for this lies in these two paragraphs in that chapter:

“ ‘What is all this uproar in the forest tonight?’ said the Lord of the Eagles. He was sitting, black in the moonlight, on the top of a lonely pinnacle of rock at the eastern edge of the mountains. ‘I hear wolves’ voices! Are the goblins at mischief in the woods?’ …

Eagles are not kindly birds…They did not love goblins, or fear them. When they took any notice of them at all…they swooped on them and drove them shrieking back to their caves, and stopped whatever wickedness they were doing.” (The Hobbit, Chapter 6, “Out of the Frying-Pan into the Fire”)

The eagles’ intervention, then, is initially depicted as simply a reaction to a repeated annoyance, which seems fair enough, if we accept that the eagles find goblins annoying, but why rescue Gandalf and Co.? And here JRRT provides an explanation more grounded in the past:

“The wizard and the eagle-lord appeared to know one another slightly and even to be on friendly terms. As a matter of fact Gandalf, who had often been in the mountains, had once rendered service to the eagles and healed their lord from an arrow-wound.”

With this in mind, perhaps the eagles’ reappearance just in the nick of time in Chapter 17, “The Clouds Burst”, would seem equally justified, because of the earlier explanation of their hatred of goblins?

Certainly that seems more likely than the sudden eruption of Beorn into the battle. Even the author, having introduced him, seems to throw up his hands, saying only

“But even with the Eagles they were still outnumbered. In that last hour Beorn himself appeared—no one knew how and from where.” (The Hobbit, Chapter 18, “The Return Journey”)

But we’re interested in the eagles and their return in The Lord of the Rings, so I’ll leave this problem, saying like Tolkien, I also have no idea how Beorn appeared—although, as one who is so in touch with the natural world, perhaps Beorn had gotten word earlier from elements in that world about the death of Smaug and the gathering of the goblins?

Back in December, 2015, CD, the founders of doubtfulsea.com, had posted a piece about the rescue of Gandalf from Orthanc

(a Ted Nasmith image—and a really beautiful one!)

(“Plot or Blot?” 23 December, 2015), in which we expressed puzzlement about how the Jackson film had depicted the event. In the film, Gandalf seems to have a conversation with a moth

and then an eagle just appears, like an airborne Uber driver, which leaves about as much unanswered as JRRT’s lack of explanation for the appearance of Beorn at the battle. In fact, Gandalf has a very logical explanation. Earlier, he had met Radagast, a fellow wizard, and, upon hearing news from him of the reappearance of the Nazgul in Middle-earth, had requested:

“ Send out messages to all of the beasts and birds that are your friends. Tell them to bring news of anything that bears on this matter to Saruman and Gandalf. Let messages be sent to Orthanc…

And the Eagles of the Mountains went far and wide, and they saw many things: the gathering of wolves and the mustering of Orcs; and the Nine Riders going hither and thither in the lands; and they heard news of the escape of Gollum. And they sent a messenger to bring these tidings to me.

So it was that when summer waned, there came a night of moon, and Gwaihir the Windlord, swiftest of the Great Eagles, came unlooked-for to Orthanc; and he found me standing on the pinnacle. Then I spoke to him and he bore me away, before Saruman was aware. I was far from Isengard, ere the wolves and orcs issued from the gate to pursue me.” (The Fellowship of the Ring, Book Two, Chapter 2, “The Council of Elrond”)

Gandalf’s initial friendship with the lord of the eagles in The Hobbit had just sufficed, I think, as a justification for rescue, but this explanation, better grounded in the story, is a much stronger one, which also suggests JRRT’s growth as a story-teller.

It’s interesting, however, that the second appearance of the eagles, repeating, at the Morannon, their attack on the goblins in The Hobbit, is aborted as, just when they begin their swoop downwards, the hosts of Mordor waver, turn, and then suddenly everything collapses:

“…the earth rocked beneath their feet. Then rising swiftly up, far above the Towers of the Black Gate, high above the mountains, a vast soaring darkness sprang into the sky, flickering with fire. The earth groaned and quaked. The Towers of the Teeth swayed, tottered, and fell down; the mighty rampart crumbled, the Black Gate was hurled in ruin; and from far away, now dim, now growing, now mounting to the clouds, there came a drumming rumble, a roar, a long echoing roll of ruinous noise.”

(The Return of the King, Book Six, Chapter 4, “The Field of Cormallen”)

(Another Ted Nasmith—and all I can say is Wow!)

The arrival of the eagles, however, leads to their final use: a second rescue, that of Frodo and Sam, organized by Gandalf:

“And so it was that Gwaihir saw them with his keen far-seeing eyes, as down the wild wind he came, and daring the great peril of the skies he circled in the air: two small dark figures, forlorn, hand in hand upon a little hill, while the world shook under them, and gasped, and rivers of fire drew near. And even as he espied them and came swooping down, he saw them fall, worn out, or choked with fumes and heat, or stricken down by despair at last, hiding their eyes from death.

Side by side they lay; and down swept Gwaihir, and down came Landroval and Meneldor the swift; and in a dream, not knowing what fate had befallen them, the wanderers were lifted up and borne far away out of the darkness and the fire.” (The Return of the King, Book Six, Chapter 4, “The Field of Cormallen”)

A final deus ex machina? Gandalf—and we—know that the Ring has been destroyed, as it’s clear that Sauron and his kingdom have crumbled, which would only occur if the Ring was gone. He is also well aware of where that destruction had to happen. That location is a good distance away, at the foot of Orodruin.

Gandalf is only presuming, of course, that Frodo and Sam somehow have survived the destruction, but is willing to try to find them. Considering the distance, as well as the level of destruction which Mordor is undergoing, logically speaking, the eagles, who were already at the Morannon, seem like a logical choice for a rescue attempt. As well, since we have seen Gwaihir rescue Gandalf earlier from Orthanc (and a second time, from Gandalf’s description, when he returns to life after his duel with the Balrog), the possibility of a third rescue has been set up all the way back in Book Two. Thus, for me, this is as believable as that first rescue, and not something created simply to allow the author to escape from a dramatic situation he would be unable otherwise to resolve—not a deus ex machina, but aquilae e nubibus—eagles from the clouds.

Thanks, for reading, as ever.

Stay well,

Keep an eagle eye out for goblins,

And know that, as always, there’s

MTCIDC

O

PS

If you’d like to see the first surviving film of The Wizard of Oz, here it is, from 1910:

https://archive.org/details/The_Wonderful_Wizard_of_Oz/WonderfulWizardofOz1910.mpg

It’s silent and less than 15 minutes long, but how interesting to see what film makers at the very beginning of their craft will make of such a story.