Tags

C.S. Lewis, Frozen, Game of Thrones, George R.R. Martin, Hadrian's Wall, Hans Christian Andersen, Kay, Middle-earth, Mile castle, Puddleglum, Queen Elsa, Rammas Echor, The Chronicles of Narnia, The Lion The Witch and the Wardrobe, The Lord of the Rings, The Night Watch, the Pevensies, The Snow Queen, The White Witch, Tolkien, Westeros, White Walkers, Winter is Coming

Dear Readers,

Welcome, as ever.

We were playing Sortes Tolkienses yesterday. That’s the game where we close our eyes, open The Lord of the Rings to any page, then put our finger on a line to see if we can write about it.

On page 1042 of our edition, our finger fell upon:

“…you may stay here till the Witch-king goes home. For in the summer his power wanes, but now his breath is deadly, and his cold arm is long.” (The Lord of the Rings, Appendix A)

The Witch-king? Oh, we thought—that Witch-king.

He has a very long history in Middle-earth, being “probably (like the Lieutenant of Barad-dur) of Numenorean descent” (from Hammond and Scull, The Lord of the Rings: A Reader’s Companion, 20, Note 5) and, in the quoted context rules Angmar

with a command to destroy the northern Numenorean kingdom of Arnor.

What caught our attention, however, was that idea of a “cold arm”. This might be metaphorical—except for that “in summer his power wanes”, suggesting that, if he can’t control the weather, he can at least use it to his advantage. And this set us thinking about stories in which winter was either controlled by someone or was, itself, the antagonist.

First, there is Hans Christian Andersen’s The Snow Queen (1845). Although this shares a title with a 2013 Disney film, there is really nothing else to link them. The Disney film has, of course, the Princess Elsa, whose enchanted hands can turn the world into winter (perhaps like the Witch-king?).

Andersen’s long fairy tale (in seven parts, or “stories”, historier, in Danish) is about the abduction of a boy and his rescue by his friend, a girl. The boy is being held by the Snow Queen, who lives in a far-off palace made of snow, the windows and doors of icy wind, lit by the Northern Lights.

What particularly caught our attention here was the manner by which the boy, Kay, was stolen. He hitched his sled to the back of a sleigh, only to find that it was driven by the Snow Queen, who takes him under her robe.

Liz Bobzin, “The Snow Queen and Kay”

This took us to the White Witch of The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe (1950), the first of C.S. Lewis’ Narnia books.

She picks up one of the Pevensie children, Edmund, in her sleigh and, while she doesn’t abduct him physically, she corrupts him by playing upon his greed and vanity.

This is an illustration of the Witch from the original 1950 book, and here are two later interpretations—the first is from the 1988 BBC production

the second from the 2005 film.

(We like both versions—we don’t mind the Steiff Aslan in the BBC production

and who could ever be a better Puddleglum than Tom Baker, the fourth incarnation of Dr. Who, in the BBC The Silver Chair, 1990?

We do worry a bit, however, about the changes made to the film versions of Prince Caspian, 2008, and The Voyage of the Dawn Treader, 2010. They’re not so drastic as those we’ve come to expect from P. Jackson’s writers, but, especially in Prince Caspian, there is a tendency to change things for what appear to be marketing reasons…)

As in what appears to be the case of the Witch-king, the White Witch can control the weather and has imprisoned all of Narnia

in snow and ice for a century—“always winter, never Christmas”.

The idea of a world of winter then brought us to George R.R. Martin’s A Game of Thrones, both the novels and the impressive (and addicting) television series. In the world of Thrones, the large island of Westeros—

and the whole world, for that matter, has once suffered a winter which lasted for a generation and the fear of its return always casts a shadow over the present. During that time, the creatures known as the White Walkers appeared from the north, with armies of animated dead, and were only driven back at great cost. To prevent their return, the surviving humans built an immense wall, 700 feet high, 300 miles long, which effectively blocks entry to the lower two thirds of Westeros.

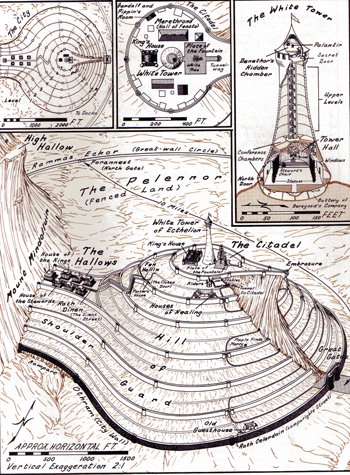

In an earlier posting, we discussed the Rammas Echor, the outer boundary wall which protects the Pelennor and Minas Tirith, and what we believe to be a major influence upon Tolkien’s idea, Hadrian’s Wall, which divides England from the lands to the north.

Unlike The Wall in Thrones, it is under a hundred miles long, was never more than 16 to 20 feet high, and was built of turf, timber, and stone, not solid ice. It was, however, a complex construction, with 17 forts behind it

and a smaller fort (now called a “mile castle”) at the end of each mile,

with small towers set in between the mile castles.

It was garrisoned with thousands of soldiers over its years of occupation (begun 122AD, finally abandoned in the 5th century).

In Thrones, this job has been taken on by The Night Watch, a rather haphazard collection of volunteers and conscripts.

And, south of them, the lands of the Stark family, Wardens of the North, whose motto—a warning of the dreaded future—forms the title of this posting.

Thanks, as always, for reading.

MTCIDC

CD