Des. The poore Soule sat singing, by a Sicamour tree.

Sing all a greene Willough:

Her hand on her bosome her head on her knee,

Sing Willough, Willough, Wtllough.

(Shakespeare, Othello, Act 4, Scene 3, from the First Folio, 1623—here’s a LINK to the Folio: https://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/doc/Oth_F1/complete/index.html You can also see, from that last line, that printers weren’t always so accurate as they might be! )

As always, dear readers, welcome.

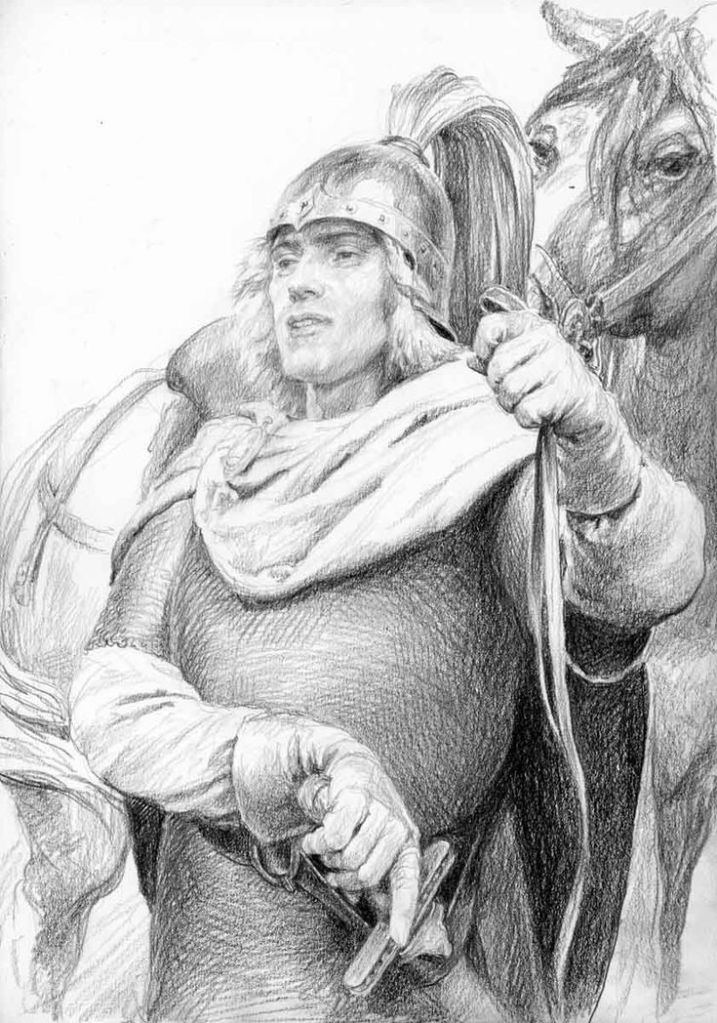

Old Man Willow,

for all that he obeys Tom Bombadil

(a lovely piece by Roger Garland)

to free Merry and Pippin:

“You let them out again, Old Man Willow!…What be you a-thinking of? You should not be waking. Eat earth! Dig deep! Drink water! Go to sleep! Bombadil is talking!” (The Fellowship of the Ring, Book One, Chapter 6, “The Old Forest”)

seems, like the Watcher in the Water, in the pool to the east of the Mines of Moria,

to remain a kind of brooding menace. As the author describes him:

“But none were more dangerous than the Great Willow: his heart was rotten, but his strength was green; and he was cunning, and a master of winds, and his song and thought ran through the woods on both sides of the river. His grey thirsty spirit drew power out of the earth and spread in fine root-threads in the ground, and invisible twig-fingers in the air, till it had under its dominion nearly all of the trees of the Forest from the Hedge to the Downs.” (The Fellowship of the Ring, Book One, Chapter 7, “In the House of Tom Bombadil”)

(JRRT’s drawing, which seems remarkably peaceful for such a threatening creature. Perhaps he is striving to suggest that the surface was that of a willow, but within was that rotten heart? Or did his love of trees prevent him from depicting the real OMW?)

As well, like Tom and like Treebeard and the Ents (and Entwives), he is, for me, one of the ancient mysteries of Middle-earth. What is he really? Where does he come from? Why is he there?

Two earlier postings (“Never a Willow”, 8/7/19 and “Never That Willow”, 8/14/19) had much to say about Old Man Willow in particular and about willows in general, including their use, for centuries, as a symbol of mourning—

(An especially beautifully-carved example)

Old Man Willow’s behavior, however, suggests that, rather than being a symbol for mourning, he can become a source of mourning and, as such, he falls into a category of deadly plants like the once ill-famed upas tree.

This is a widespread variety of tree, Antiaris toxicaria, which can be found from Africa all the way across to the western Pacific.

(This illustration is from a highly-informative and surprisingly jolly website, considering its subject matter, entitled “Nature’s Poisons”: https://naturespoisons.com/ )

Travelers’ tales reported that the plant gave off a kind of noxious fume which poisoned the landscape for 10 miles around, leaving the vicinity empty save for the bones of unwary animals and people. Although this was proven to be more than an exaggeration in the early 19th century, a deadly poison can be extracted from the tree and was used by various indigenous peoples to tip their darts and arrows.

(For more on this, see the article at “Nature’s Poisons”: https://naturespoisons.com/2019/07/17/antiarin-upas-tree-antiaris-toxicaria/ )

An even more spectacular tree—if possible—was the so-called “Man-eating tree of Madagascar”.

This was actually a hoax, first perpetrated, it seems, in an article by someone called Edmund Spencer for The New York World, first published on April 26th, 1874. As was the custom in the 18th and 19th centuries, the story was reprinted in other newspapers, including this description, which I have from The South Australian Register from later the same year. Here, the (now known to be imaginary) Mkodo tribe made the sacrifice of a woman to the tree–

“The slender delicate palpi, with the fury of starved serpents, quivered a moment over her head, then as if instinct with demoniac intelligence fastened upon her in sudden coils round and round her neck and arms; then while her awful screams and yet more awful laughter rose wildly to be instantly strangled down again into a gurgling moan, the tendrils one after another, like great green serpents, with brutal energy and infernal rapidity, rose, retracted themselves, and wrapped her about in fold after fold, ever tightening with cruel swiftness and savage tenacity of anacondas fastening upon their prey.”

(quotation from The South Australian Register as found on the Nova Online Adventure website in part 2 of an article on “A Forest Full of Frights”: https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/madagascar/surviving/frights2.html Warning: if things which threaten your eyes disturb you, DO NOT READ THE SECTION ENTITLED “EYE SORE”!)

This sounds rather like an acrobatic variety of Venus flytrap, a predator plant I was surprised to learn was not a jungle plant, but grows in subtropical areas of the US, in North and South Carolina.

An insect victim walks across its sensitive pad centers and it instantly closes around it, then beginning the digestive process.

This makes me wonder what would have happened to Merry and Pippin, had there been no Tom Bombadil…

As ever, thanks for reading.

Stay well,

Never drowse near a carnivorous willow,

And remember that, as always, there’s

MTCIDC

O

PS

For an especially disturbing short story about such things, read Algernon Blackwood’s “The Willows” (from his 1907collection, The Listener and Other Stories here: http://algernonblackwood.org/Z-files/Willows.pdf )

PPS

And a friend reminds me that there’s another very destructive, if not carnivorous, willow I should mention.

PPPS

For more on poisonous plants, see: https://www.learnaboutnature.com/plants/carnivorous/