Tags

Arthur Rackham, Baron Friedrich de la Motte Fouque, Brothers Grimm, Charles Dickens, Charles Perrault, Charles S Evans, Cinderella, Disney, Dornroeschen, Edgar Taylor, ETA Hoffman, French Revolution, George Cruikshank, German Popular Stories, Hans Christian Andersen, Histoires ou Contes du Temps Passe, Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm, James Robinson Planche, Kinder und Hausmaerchen, La Belle au Bois Dormant, Little Briar-Rose, Louis XIV, Louis XVIII, Mariinski Theatre, Napoleon, Robert Samber, Sleeping Beauty, St Petersburg, Tchaikovsky, The Little Mermaid, Undine

Welcome, as ever, dear readers.

In our last, we began talking about the fairy tales of Charles Perrault (1628-1703), originally published under the rather vague title, Histoires ou Contes du Temps Passe, (“Stories or Tales of the Past”) in 1697.

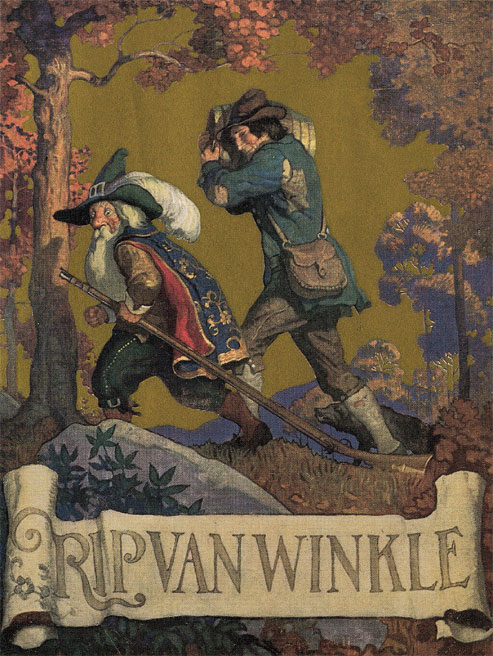

Among his stories was one entitled “La Belle au Bois Dormant”—literally “The Beautiful Girl in the Sleeping Woods”, which we English-speakers call “Sleeping Beauty”. We had said that we thought it would be interesting to look at various treatments of that story over time and, so far, we’ve discussed James Robinson Planche’s (plawn-SHAY) two works, an 1840 “extravaganza” (a kind of very early musical comedy) and his 1868 story-in-verse version (here’s the first edition).

Planche could read the French original, but those whose knowledge of French was confined to menus could find English translations dating all the way back to the first, that of Robert Samber, in 1729.

(This image, by the way, explains not only why English-speakers call this story “Sleeping Beauty”, but also why we call the stories as a group “Mother Goose Tales/Stories”. Please see our previous posting for where Mother Goose came from in Perrault.)

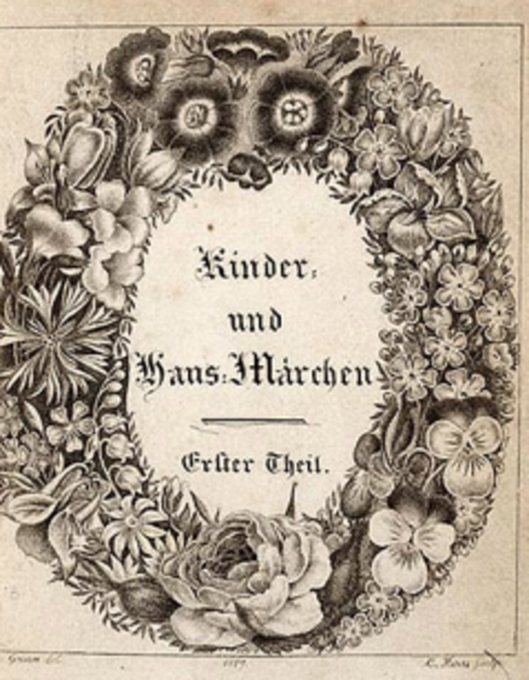

In the early 19th-century, a competitor to Perrault appeared. In 1812, two German scholars, Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm (1785-1863, 1786-1859,)

began publication of a work which they would enlarge numerous times through the first half of the 19th century, Kinder und Hausmaerchen (something like “Children’s and Domestic Wondertales”), the first volume of which first appeared in 1812.

“Sleeping Beauty” appears as #50, under the title Dornroeschen, “Little Briar-Rose”. This is like the Perrault story, but not the same, providing an alternate version of the tale. For those without German, an English translation was published in 1823.

Although their names aren’t on the title page, this is a collaboration between Edgar Taylor (1793-1839), translator,

and George Cruikshank (1792-1878), illustrator.

Of the two, Cruikshank is the better-known. Originally, he was famous as what we now call an “editorial cartoonist”, creating images critical of politicians and political events of his time. Here is his 1823 caricature of Louis XVIII of France (reigned 1814-1824 with a little gap in 1815 when Napoleon came back briefly from exile on Elba).

His public relations people wanted Louis to look like this:

to remind them that he was the direct descendant of Louis XIV, the famous “Sun King”, a grand and heroic figure in recent French history.

In reality, Louis was old and fat and looked more like this—

It wasn’t about Louis per se, weak and temporary monarch though he was, so much as the long-standing English/French rivalry/hostility, which went back for centuries and which had intensified during the Revolutionary and Napoleonic wars, stretching almost without a break from 1792 to 1815. Napoleon, as representative of what the English of the time saw as revolution-which-led-to-chaos-and-worse, was a regular target from the later 1790s on and Cruikshank certainly aimed his pen and brush at him—as in this mocking depiction of the fate of Bonaparte after his first abdication in April, 1814.

Political commentary aside, Cruikshank, as we see in his illustrations for the Brothers Grimm (and isn’t it odd that we never say, in English “the Grimm Brothers”—which sounds either like a menacing secret society or perhaps an old, established firm of teakwood importers), was involved in all sorts of illustrating, including a second volume of the Grimms, in 1826. This is the 1868 reprint which the editor says duplicates in one volume the text and illustrations of the original two. (We include a LINK so that you can download your own copy.)

As well, he illustrated the original serialized version of Charles Dickens’ (1812-1870) Oliver Twist (1837-1839). This is a famous scene near the end of the novel, where the main villain, Fagin, is in the condemned cell, awaiting dawn and his execution. Dickens was famous for his performance of this.

On a more cheerful note, here’s Cruikshank’s sketch of Dickens himself from 1836.

The Grimms’ version of the “Sleeping Beauty” story is combined with that of Perrault in our next example. It’s the 1920 The Sleeping Beauty,

text by Charles S. Evans (1883-1944), of whom we have found no picture, and Arthur Rackham (1867-1939) of whom this may be our favorite picture.

The year before, Evans and Rackham had collaborated on a version of Perrault’s “Cinderella”—and we’ll talk about that in our next. The Sleeping Beauty is anything but sleepy—its illustrations practically dance off the page. (Here’s a LINK for your own copy.)

And dance itself is the basis of our last example.

In 1888, Pyotr/Peter Tchaikovsky (1840-1893)

was offered a commission for a ballet. Originally, the subject was to be a famous early German Romantic novella, Undine (un-DEE-neh), written by the Baron Friedrich de la Motte Fouque (foo-KAY) (1777-1843),

and published in 1811. It’s the story of a knight and a water spirit and shares the basic plot of HC Andersen’s later “The Little Mermaid”. Here’s an illustration from Rackham’s 1909 version.

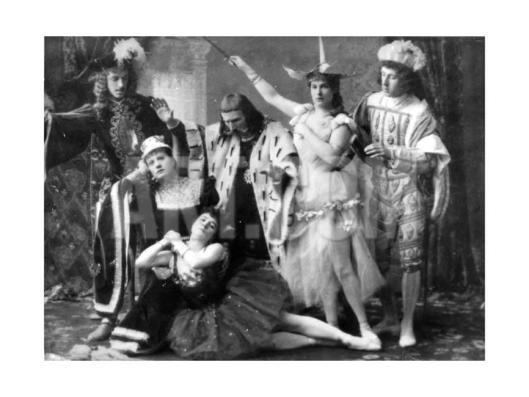

As things developed, however, this story was replaced by the Perrault/Grimms’ “The Sleeping Beauty”, which first appeared at the Mariinski Theatre

in St Petersburg in January, 1890. We are lucky to have a number of photos of the original production and cast.

And here’s a LINK to a suite (selection) of music from the ballet—but the full ballet is available on YouTube and we hope that you like this suite so much that you’ll try the whole thing.

In our next, we’ll move on to a second Perrault story, “Cinderella”.

Thanks, as always, for reading.

MTCIDC

CD

ps

If you’re a regular reader, you’ll know that we can rarely resist adding something more. In fact, in this ps, we add two somethings more.

First, before Undine was proposed for a ballet, it was the subject of an opera by the strange and wonderful German Romantic author and composer ETA Hoffmann (1776-1822).

Here’s a LINK to the overture. In a future post, we’ll have more to say about Hoffmann…

Second, as people who grew up on Disney, we can’t close without mentioning Disney’s 1959 Sleeping Beauty, with its attempt at a new style of visual presentation—as well as its use of Tchaikovsky’s music as the basis of its score. If you haven’t seen it, we certainly recommend it, especially for its combination of elements of the older look of such films as Cinderella (1950) with a newer, simplified one.