Welcome, dear readers, as ever and Happy New Year (for those who follow the Gregorian Calendar).

Vlad the Impaler has turned up more than once in this blog.

He does so primarily because he is the wonderfully menacing villain of Bram Stoker’s 1897 novel, Dracula.

I’ve now taught this book several times and it always seems to catch student attention—not surprising, even considering the denser language of late Victorian fiction and the sometimes outdated social attitudes, since the basic story, that the equivalent of a combination of highly-intelligent predator

and virus

has plans to invade England and to use the first-class railway system

to spread his infection, is so well handled that it still seems disturbing even now, 123 years after its initial publication–and further proof of this is that it’s never been out of print in its history.

Each time I teach it, something different always pops out. This time, it was just how much of Dracula’s ultimate defeat is owed to the daily work of Victorian offices.

This might seem very odd, at first. Imagine the terrifying Terminator

or the saliva-dripping Alien

destroyed by a color copier.

And it requires more than such work to put an end to the vampire and his designs—stakes

and Bowie knives

a Gurkha kukri,

and even Winchester rifles,

but major weapons in the campaign are this

and this

and this.

The novel begins, in fact, with the first of these. The first protagonist we meet is Jonathan Harker, a clerk for an English attorney, on his way in a public coach, called a “diligence”,

to meet a client, a nobleman who lives deep in the mountains of Transylvania.

He keeps a journal—in shorthand, a page of which might look like this:

Shorthand has a very long history in the West. The earliest mention I can find is in Plutarch’s (c46-119AD) life of Cato the Younger ( 95-46BC) , where it is said that the only one of his Senate speeches survives because the Consul, Cicero (106-43BC),

had stationed shorthand writers in the Senate, who took down the speech as it was spoken (Plutarch, Life of Cato the Younger, Section 23, Paragraph 3—if you’d like to read this for yourself, here’s a LINK to the whole text—just scroll down to the appropriate section: https://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/Plutarch/Lives/Cato_Minor*.html )

There is, as is so often the case with ancient details, a good deal of discussion, both in the classical world and among later scholars, about how this shorthand came into being. One possibility was that it came through Cicero’s secretary (and slave), Tiro, and the practice, which included increasingly long lists of symbols, called “Tironian notes”, continued in one form or other up through the Renaissance.

The first modern system for English-speakers was created by John Byrom (1692-1763).

Instead of being based upon a huge collection of symbols, Byrom’s system was based upon capturing sounds—here’s a 1730s journal entry by him using his method.

His method became a common one after its posthumous publication in 1767 as The Universal English Short-Hand

with a rival in that of Samuel Taylor’s 1786 An Essay Intended to Establish a Standard for a Universal System of Stenography, or Short-hand Writing, which appears to have overtaken and replaced Byrom’s method.

And I imagine that this was the system which the young Charles Dickens (1812-1870)

taught himself so that he could get his first writing job—as a Parliamentary debate reporter.

In time, however, this method was replaced by that invented by Sir Isaac Pitman (1813-1897)

first published in 1837.

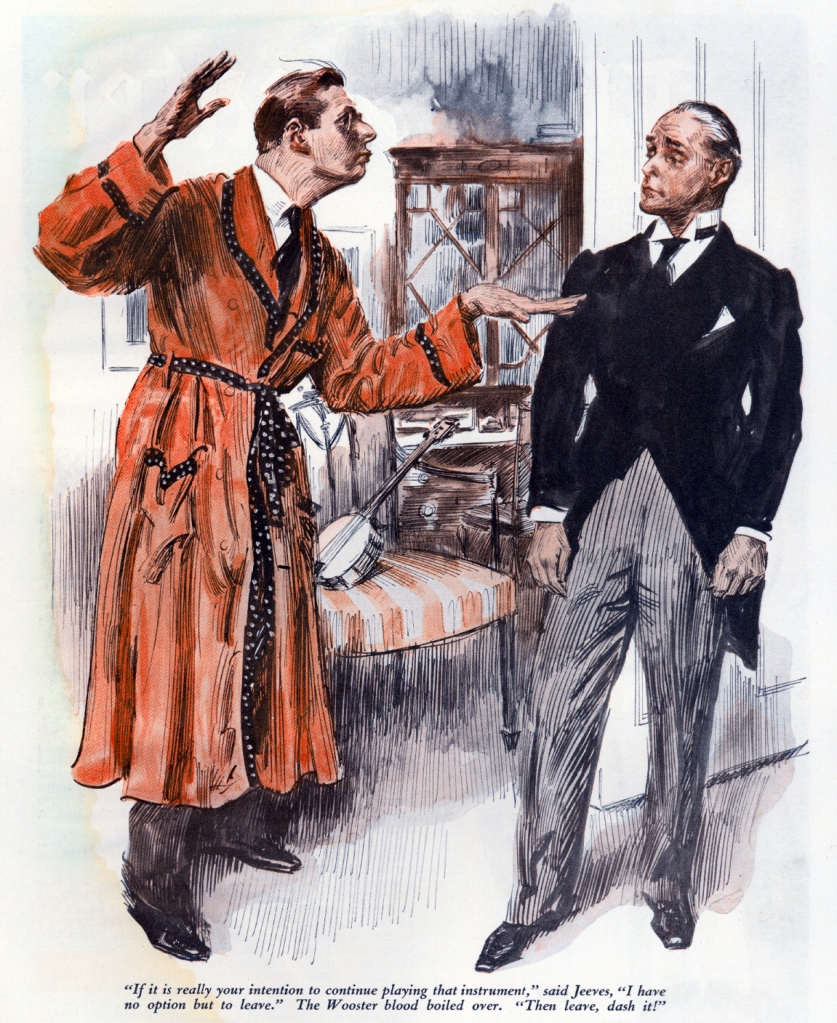

Not only does Jonathan keep a diary in shorthand, but his wife-to-be, Mina, tells us in a letter to her friend, Lucy Westenra, that she has been studying and practicing it as well, so that

“When we are married I shall be able to be useful to Jonathan, and if I can stenograph well enough I can take down what he wants to say in this way and write it out for him on the typewriter, at which also I am practising very hard.” (Dracula, Chapter V—if you want to follow along, here’s a LINK to the text I’m using—it’s the 1897 American edition, available at Gutenberg: https://www.gutenberg.org/files/345/345-h/345-h.htm )

We see here two of the elements I mentioned earlier, shorthand and the typewriter.

Unlike shorthand, typewriters were relatively new in 1897. Although there had been earlier tries at its invention, the first commercially practical machine was patented in 1868

and was first manufactured in 1873.

The third element appears a little later in time as well as in Chapter V, where we meet another major character, Dr Seward, who is the director of an asylum and keeps his diary on what he calls a “phonograph”.

This is what we now call a “Dictaphone” and was the offspring of two remarkable 19th-century inventors, Thomas Edison (1847-1931)

and Alexander Graham Bell (1847-1922)

Although Edison invented sound recording, it was Bell who created the first viable medium, the wax cylinder,

which Bell then employed in the 1880s for a business function: recording thoughts on such cyclinders—

which could then be listened to and transcribed by a secretary onto paper—with pen or typewriter.

So, knowing a little something about these office weapons, how are they used in the book?

As readers, our first knowledge of Dracula comes from Jonathan Harker’s journal, which, as we’ve seen, was written in shorthand. We also know that Mina, who will become Harker’s wife, practices shorthand herself, and can type. After Harker’s eventual escape from the Count’s castle, he hands his journal to Mina, and, eventually, she reads it—and does something more. When another character, and a very important one, Professor Van Helsing, seeking information, comes to visit Mina and her now-husband, she says to him:

“If you will let me, I shall give you a paper to read. It is long, but I have typewritten it out. It will tell you my trouble and Jonathan’s. It is the copy of his journal when abroad, and all that happened. I dare not say anything of it; you will read for yourself and judge.” (Dracula, Chapter 14)

Mina adds to this a copy of her own diary, kept at the time when she and her friend, Lucy, are at Whitby, on the northeastern English coast, and Lucy is first attacked by Dracula. In time, she will do something more: listen to, and transcribe the wax cyclinders of Dr Seward’s diary–

“He accordingly set the phonograph at a slow pace, and I began to typewrite from the beginning of the seventh cylinder. I used manifold, and so took three copies of the diary, just as I had done with all the rest.” (Dracula, Chapter XVII)

Seward had treated Lucy as she fell under Dracula’s influence and, when he was baffled by what was happening to her, called in his former teacher, Professor Van Helsing and, with Mina’s professional skill, what he had seen and experienced then became part of the on-going record of Dracula and his activities.

“Manifold” is what we would call “carbon paper”, a method which allows a typist to make multiple copies simultaneously and which is sometimes still used to make copies of receipts.

This will be especially useful when Dracula enters Dr Seward’s asylum, attacks Mina (again) and tries to destroy all records of himself:

“ ‘All the manuscript had been burned, and the blue flames were flickering amongst the white ashes; the cylinders of your phonograph too were thrown on the fire, and the wax had helped the flames.” Here I interrupted. “Thank God there is the other copy in the safe!’ “ (Dracula, Chapter XXI)

What Mina has done, then, is to provide, through her office skills, as complete a record as can be constructed of Dracula’s aims and actions, not only in England, but through Jonathan’s journal, at his lair, the castle in Transylvania.

(This is Bran castle, which some believe may have been a model for Stoker.)

With it, Van Helsing has learned so much that, as he plans further action against the vampire, he will say of her:

“ “Ah, that wonderful Madam Mina! She has man’s brain—a brain that a man should have were he much gifted—and a woman’s heart.’ “ (Dracula, Chapter XVIII)

Add to that a typist’s sure fingers.

Thanks, as ever, for reading,

Stay well,

And know that, as always there’s

MTCIDC

O