Tags

Calendar, consuls, decimalized time, French Revolution, Gregorian Calendar, Julian Calendar, Julius Caesar, leap year, Napoleon, New Republican Calendar, Numa Pompilius, Pontifex Maximus, Pope Gregory XIII, Remus, Revolutionary calendar, Romans, Rome, Romulus, Sir Percy Blackeney, Tarquinius Superbus

As ever, dear readers, welcome.

Our last posting, which involved, among other things, the French Revolution, made us think of calendars.

The traditional Western calendar has been with us a long time, beginning with the Romans.

They believed that the calendar had originally been devised by the founder of Rome, Romulus.

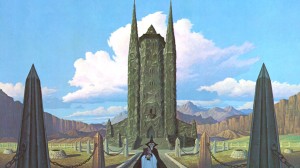

(Romulus is the one on the right. If you don’t know Roman mythology, this is part of the legend of Romulus and his twin, Remus, who were, at one time, raised by a she wolf. Romulus eventually clashed with Remus and killed him.)

Romulus produced a yearly calendar divided into 10 months and it was his successor, Numa Pompilius, who revised it by adding two months. Romulus and the rulers who followed him were traditionally believed to be seven in number (like the seven hills Rome was built on—or maybe just because 7 has been thought of as a magic number—to read more—maybe too much!—on this, see this LINK).

(If you’d like to improve your knowledge of early Rome—at least as the Romans believed it–here’s a neat way to remember these mythological kings in order.)

When the last of these kings, Tarquinius Superbus (“Tarquinius the Arrogant”) was overthrown in 509BC (as always, according to Roman tradition), he was replaced by two consuls, who were elected annually.

Because of the annual nature of their election, the consuls in time became the marker for each year—the year being designated in documents by their names. In Latin, this was written as, for example, “L. Sulpicio et M. Canonico consulibus”—“Lucius Sulpicius and Marcus Canonicus being the consuls”—that is, “in the year during which LS and MC were the consuls”.

In time, two events complicated this time-keeping to the point where it was a mess.

First, this calendar was based upon the lunar year of 355 days. Set against the 365 ¼ days of the solar year, there was always a gap and so the months and the seasons could begin to separate. To close this gap, an intercalary month of 27 or 28 days was sometimes inserted, but, seemingly, without the strict regularity the marking of time really needed. Second, the chief priest of Rome, the Pontifex Maximus, with his assistants, the College of Pontiffs, had the legal (and religious) right to change the calendar and, if you think about this in political terms (and the Romans did), you can see what a less-than-neutral Pontifex could do: add days to the term of consuls he favored and subtract days from those he didn’t, potentially making the synchronization of lunar, solar, and consular years fall apart completely.

When Julius Caesar (100-44BC)

came to power, he ordered the reformation of the calendar, but retained the old lunar calendar of 355 days, dividing the year into 8 months of 29 days and 4 of 31, plus adding an intercalary month of 27 or 28 days every two years. This meant that, every 4 years, the total number of days, divided by 4, would come to 366 ¼–which meant more regularity, but trouble to come, in time (literally), especially because the College of Pontiffs was still in charge of maintaining things, which it doesn’t seem to have done with the necessary diligence.

In fact, the story is more complicated yet than this, but this at least gives us the so-called “Julian Calendar”, which was in use in the West from Caesar’s time until the Renaissance. In 1582, by the direction of Pope Gregory XIII,

to correct the seasonal drift which had gradually occurred over the centuries, the Julian calendar was reformatted, adding a full day to the month of February (February 29th) every fourth year. The first year with such an addition to February was the next year, 1583, but, to help the calendar and actual year rejoin, Gregory ordered the addition of 11 days to October of 1582, so that October 4th became October 15th. We hope that all of this is clear?

For people who grew up with all of this adding here, changing there, it’s left us with a sort-of rhyme to remember what months now have how many days:

“Thirty days hath September,

April, June, and November.

All the rest have thirty-one—”

And then the thing breaks down into something like “Except February, which has twenty-eight, except every fourth year, when it has twenty-nine.”

So, why did the French Revolution remind us of calendars?

One of the main bases of the French Revolution, the thinkers of the Revolution would say, was the idea of REASON. In fact, for a short time, some revolutionaries attempted to replace Christianity with the worship of a goddess by that name.

Reason brought about the initial attempt to convert France by law to the metric system in 1795. Even before that, however, there had been a program to decimalize everything possible, including the currency and the time of day—here’s a watch from 1795 with both kinds of time marked on it.

Of course, the calendar would be a target and, between 1793 and 1805, France would mark its years by it in 12 months of 30 days each, each month divided into 3 decades. To keep the balance between months and seasons, five or six extra days were added to the end of the year. To remove any trace of the old royal (and religious) past, the new months were renamed—here’s the calendar. As you can see, the renaming was meant to reflect seasonal weather.

The committee (one major feature of the Revolution was that seemingly everything was created by a committee) even came up with the names for every day, the names being something ordinary to which the day was devoted.

If you look at the column marked “Nivose”, you can see that the first four days are “neige/glace/miel/cire”—“snow/ice/honey/wax” (although those first two make perfect sense in a month called “Snowy”, we’re a little unclear about “honey” and “wax”).

Napoleon participated in a coup which ended revolutionary government in 1799 (18 Brumaire, Year VIII-9 November, 1799).

He tolerated the revolutionary calendar for the next 5 years, but, after he made himself emperor, 11 Frimaire, Year XIII–2 December, 1804,

a decree was issued that, beginning 1 January, 1806, the old Gregorian calendar would be reinstated.

During the days of the Terror

and the Scarlet Pimpernel, however,

when Sir Percy Blakeney put down a rescue date on his calendar in Paris, he would have written January 1, 1794 as “day 2 of the second decade of Snowy, year II, “ a day devoted to “Argile”—“Clay”.

Thanks, as always, for reading.

MTCIDC

CD