Tags

Alfred Noyes, Claude Duval, Dennis Moore, Dick Turpin, Dr Syn, gibbet, Highwaymen, Industry and Idleness, Lupine Express, Lupine flower, Monty Python, Robin Hood, Romney Marsh, Russell Thorndike, Smugglers, The Four Stages of Cruelty, Tyburn, William Hogarth, William Powell Frith

After our last posting, where we were in southeast England with 18th-century smugglers, we’ve found ourselves traveling inland, but still on the same theme: interesting evil-doers.

Dr. Syn, aka “The Scarecrow”

was a fictional character created in 1915 by Russell Thorndike,

but based upon actual smuggling gangs who worked along the coast of the area called Kent.

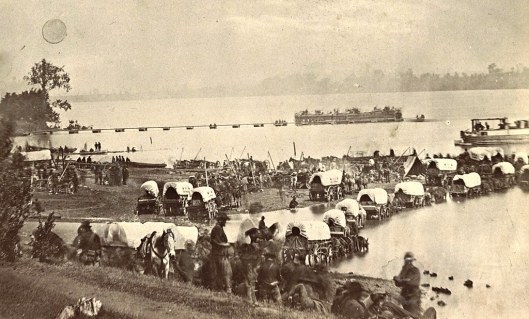

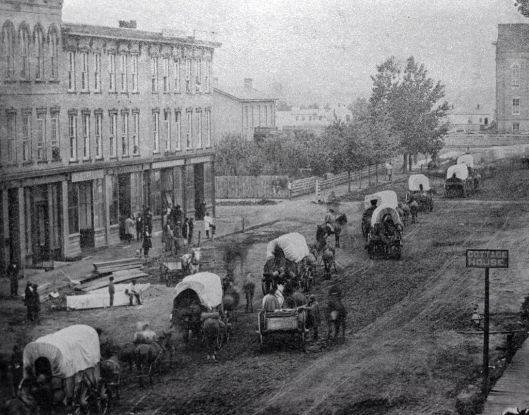

Such people robbed the government of revenue, removing goods which would have been taxed, sometimes heavily, at legitimate ports of entry. Our next 17th-18th-century evil-doers use the more personal approach, behaving in the tradition of Robin Hood,

the difference being that, rather robbing the rich and giving to the poor, highwaymen robbed from the rich—or almost anyone they caught on the public roads—and kept it. This could mean an individual on foot,

or on horseback,

or in a carriage,

or in a coach.

These men could become quite well-known in life, like Dick Turpin, who had biographies written about him.

Turpin, and a few others, like Claude Duval,

even entered contemporary folklore. This painting, by William Powell Frith (1819-1909), depicts a piece of what appears to be that very folklore. The story goes that, once, when he had stopped a coach, Duval offered to reduce the amount taken from the gentleman inside if his pretty wife would dance with him. She did so, and Duval did as he offered.

Such behavior, real or no, may have impressed ordinary people, but the law saw highwaymen as a menace and one to be dealt with severely. Any one caught was tried and quickly sentenced to be hanged. If taken in the London area, the execution was done at a standard execution place, Tyburn.

This engraving is by William Hogarth (1697-1764), a famous artist and caricaturist of the first half of the 18th-century. It’s from a series entitled, “Industry and Idleness” (1747) and you can see who is about to suffer from the sheet of paper held in the hand of the woman in the foreground. It reads: “The Last Dying Speech and Confession of the Idle [Apprentice]”.

People in other times, from Roman gladiatorial combat to Elizabethan bear-baiting, had very different ideas from most contemporary folk when it came to open violence as spectacle. Here, we see, as was common in England at this time, a huge crowd all gathered to witness the Idle Apprentice’s death. (Public executions were only abolished in Great Britain in 1868.)

One can see part of the entertainment in what that woman is holding. A common souvenir of the event was a printed broadsheet, with a title like “Trial, Last Words, and True Confession of…”, which purported to be the dying statement of the person about to be executed.

Often these began with a generic woodcut of a hanging and might also contain other illustrations, like the one below, from 1835.

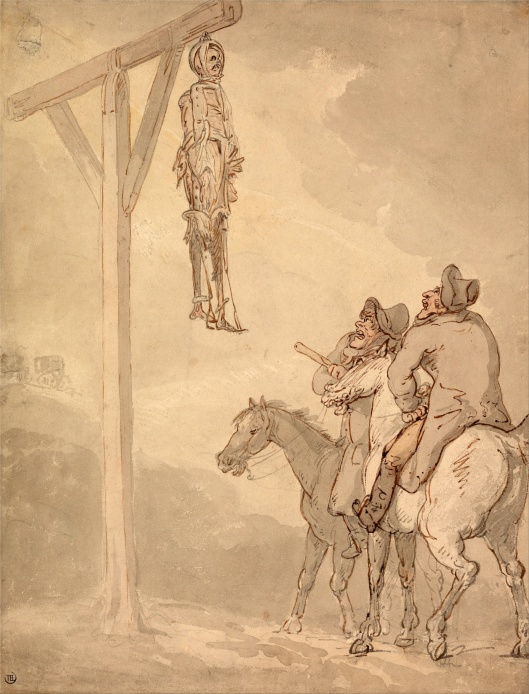

Once the execution was over, the punishment was not. The executed person’s corpse (we think that this was only males) might be displayed publicly in a kind of iron cage on a frame, called a gibbet, sometimes till the body had crumbled away.

Or, worse, it might be turned over to a medical school and used for instructional purposes.

(This is from another Hogarth series, “The Four Stages of Cruelty”, 1751. The skeleton in the background, on the right, is labeled, “MacLeane”, who was a highwayman hanged in 1750.)

We had first learned about highwaymen from a famous poem, “The Highwayman”, by Alfred Noyes (1880-1958).

Here’s a LINK so that you can read it for yourself.

But, because we can’t end on a grim note, there’s one more highwayman we want to mention. This is Monty Python’s John Cleese, playing the highwayman Dennis Moore. Moore doesn’t take money from his victims in the sketch. Instead, he robs the “Lupine Express”.

Lupines are an edible flower and, as you can see, at least the dwarf variety comes in multiple colo(u)rs.

We can’t show you the sketch, unfortunately, but we can give you the LINK to the audio recording, in which there is not only the robbery, but also a good deal of discussion about tree identification, with argument over a willow…

Considering penal laws in 18th-century England, where over 200 crimes were punishable by death, we don’t imagine that even a flower thief would have escaped the gallows, even if he did give the lupines to the deserving poor

Thanks, as ever, for reading—and, if attacked by highwaymen, try to be as well-armed as these people clearly were—

And thanks, as ever, for reading.

MTCIDC

CD

ps

And how about a highwayman music video featuring Dick Turpin, brought to you courtesy of Horrible Histories? Here’s the LINK.