Tags

Bilbo, Denethor, Fantasy, Grima, lotr, Palantir, psychology, Sam Gamgee, Saruman, Sauron, Smaug, Tolkien

Welcome, dear readers, as always.

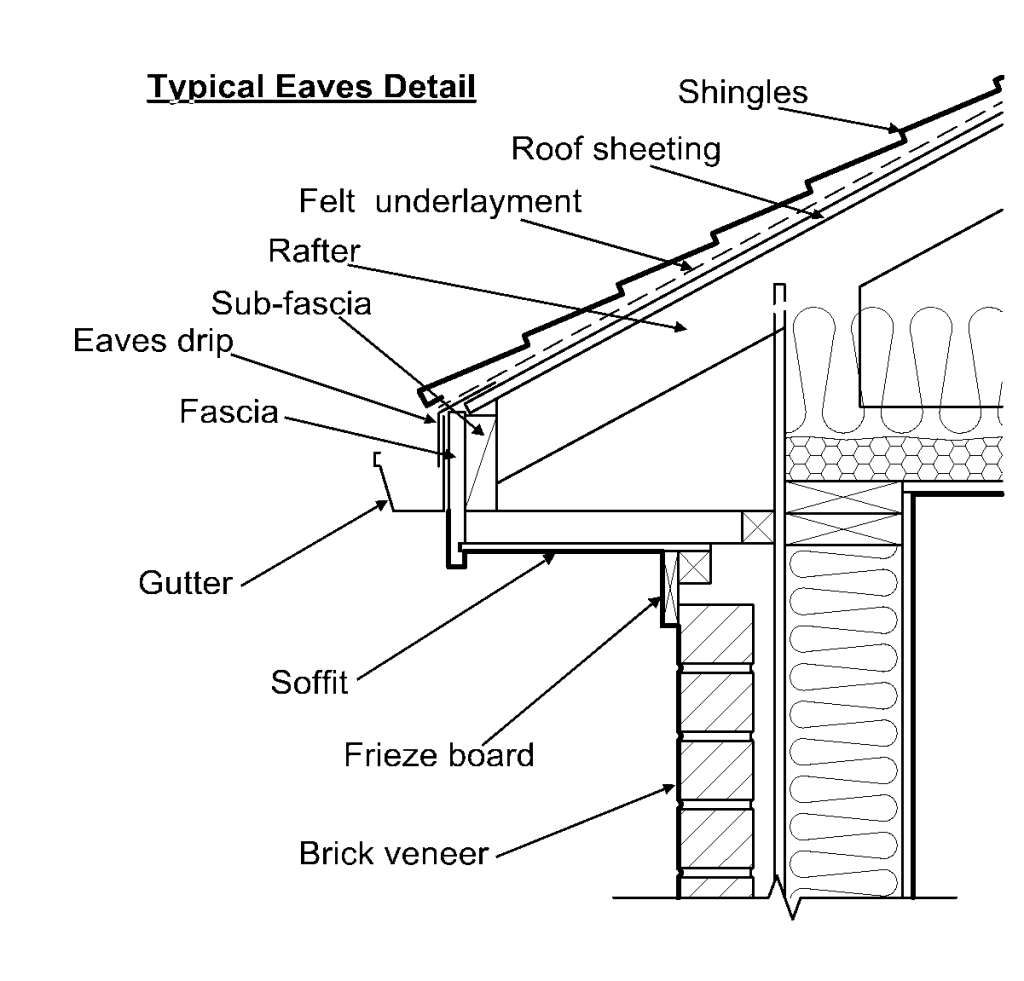

Where are “eaves” anyway, and why would you drop from them?

On a modern roof, they look like this—

If you lived in the mid-15th century, when the expression “eavesdropper” first appears, it might look like this—that’s the overhang of the thatched roof–

As Etymonline will be happy to tell you,“eaves” is from Old English “efes”, the “overhang of a roof”, plus “dropa”, “a drop (as of rain)”, so “that area of the roof from which the rain drips”. (For more, see: https://www.etymonline.com/word/eavesdrop )

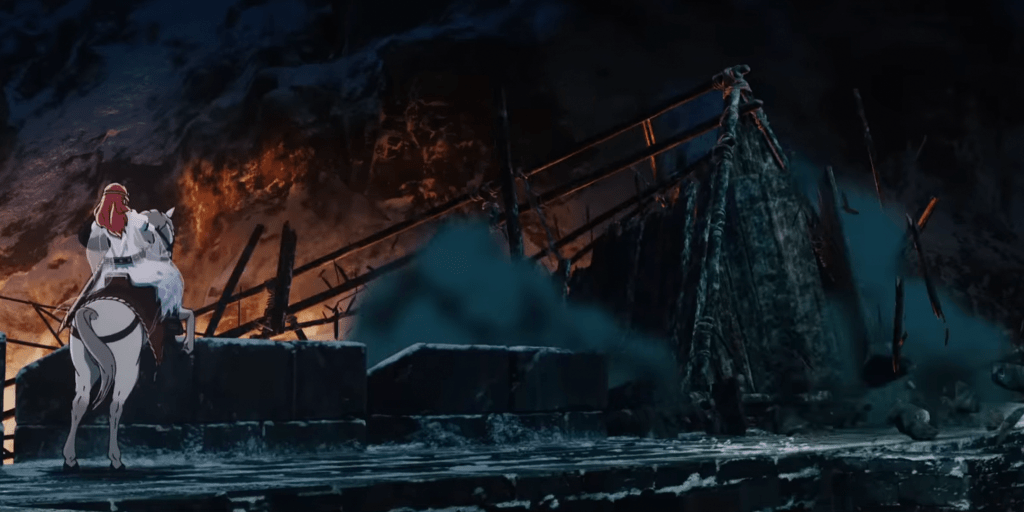

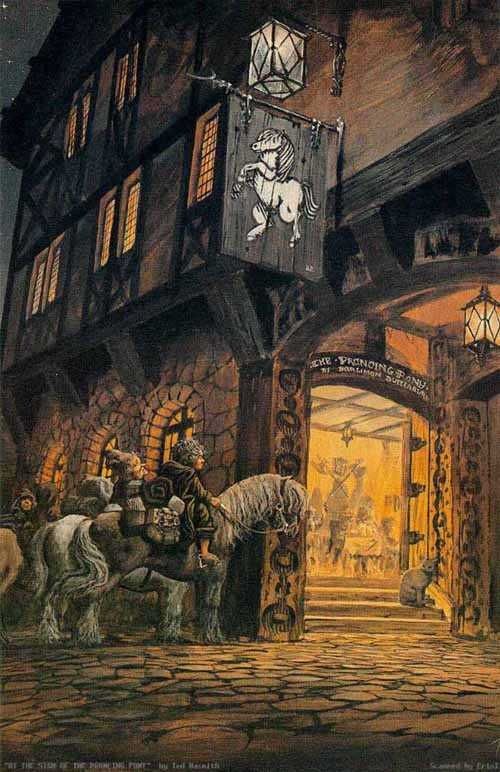

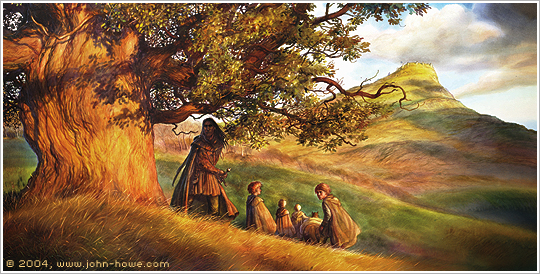

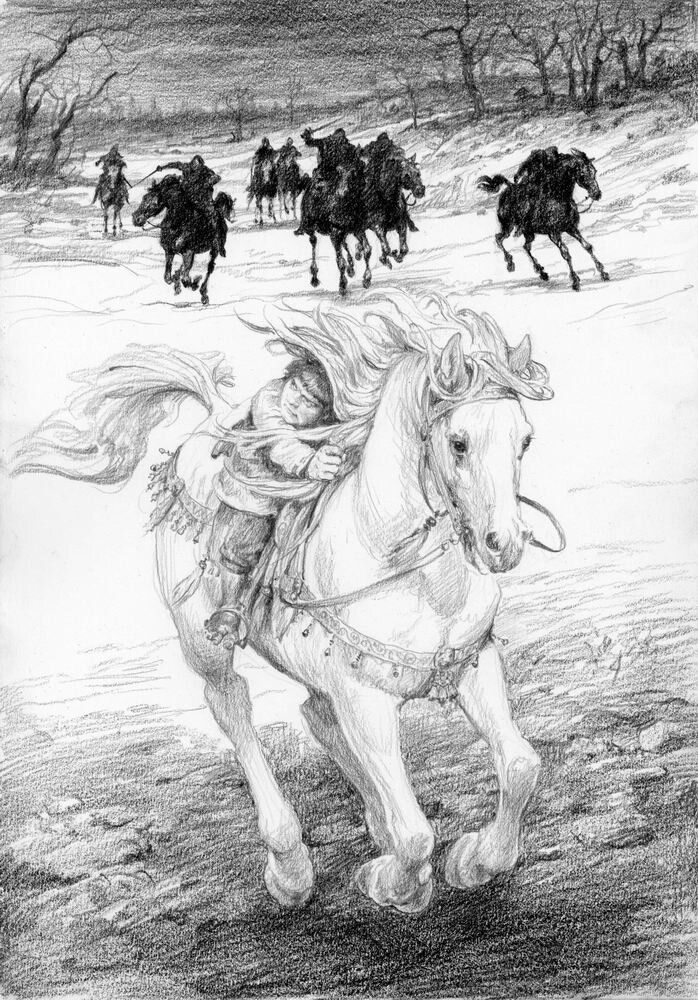

The idea, then, is that, if you wanted to listen in on an indoor conversation, you might climb on a roof, hang your head over the side, and follow someone speaking below, say at an open window—rather as Sam Gamgee does, although he does so less precariously—

(Robert Chronister)

In our modern world, more than once, I’ve found myself doing this—and probably you have, too–although inadvertently, as someone nearby has been bellowing into his/her cellphone while sitting or standing near you.

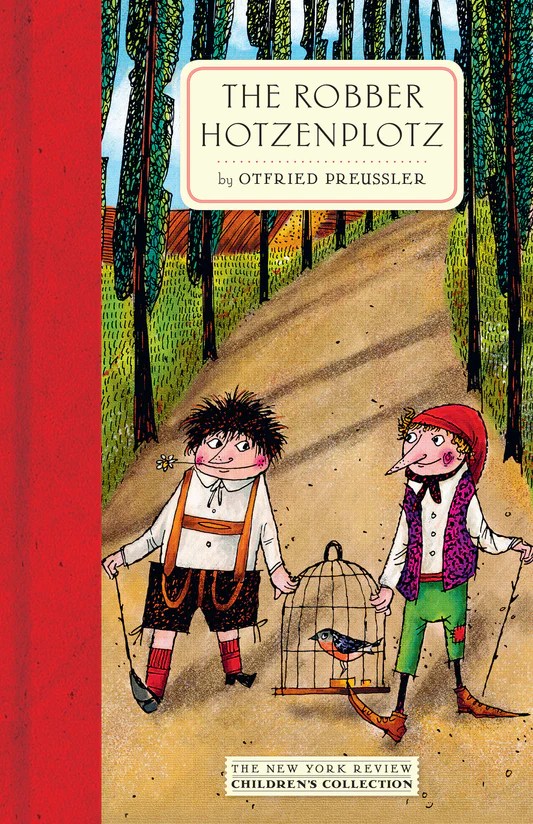

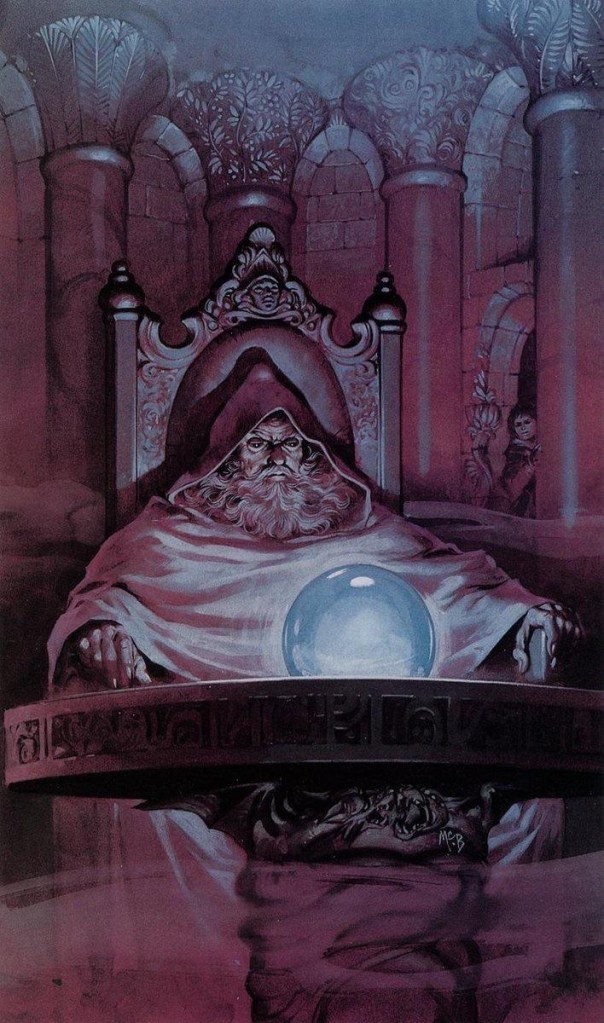

Unless the person at the other end is bellowing, too, you don’t hear that end of the conversation, only the local speaker, but it might be an interesting experiment, perhaps, to see what you could reconstruct from this end and, in this posting, I want to try to do that–not with a cellphone, but with a rather older device, a palantir,

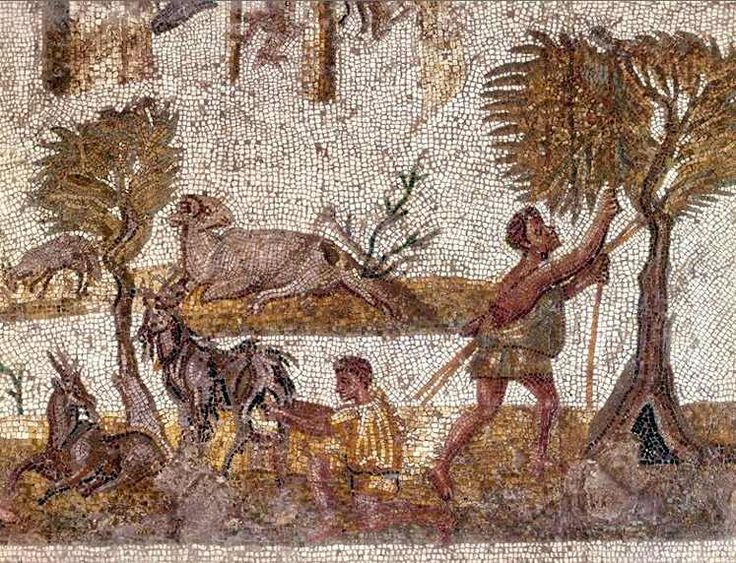

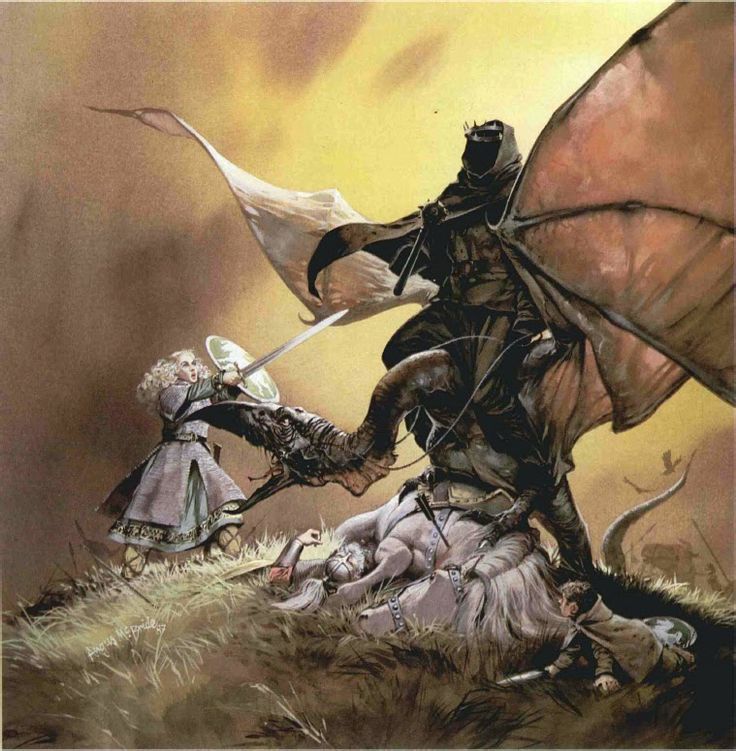

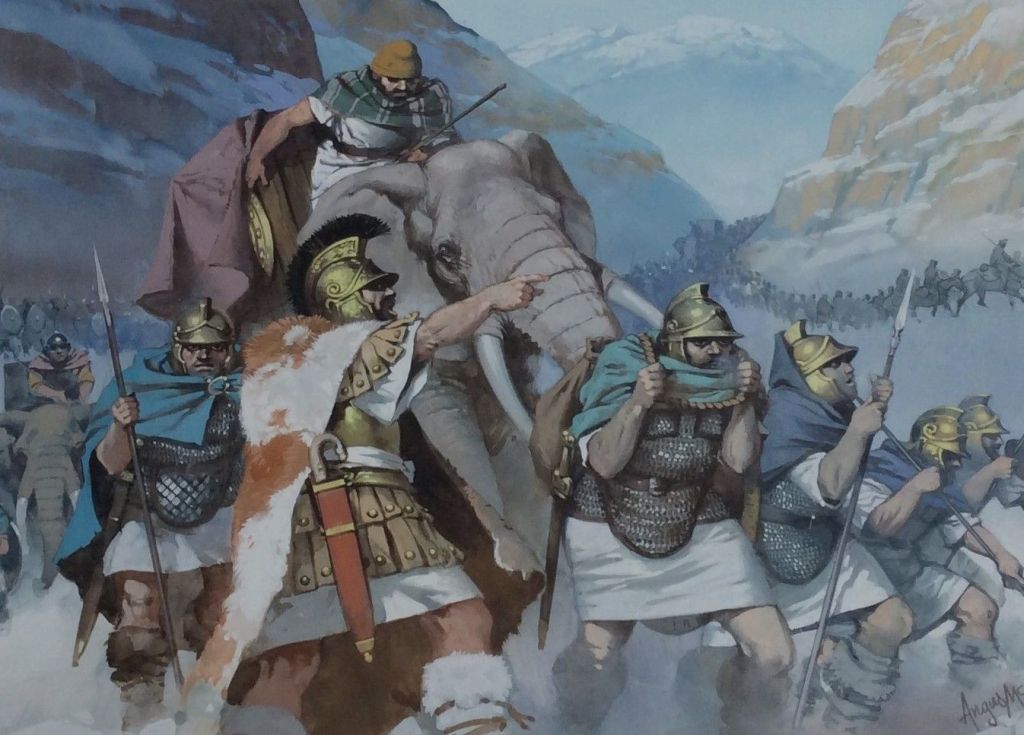

(Angus McBride)

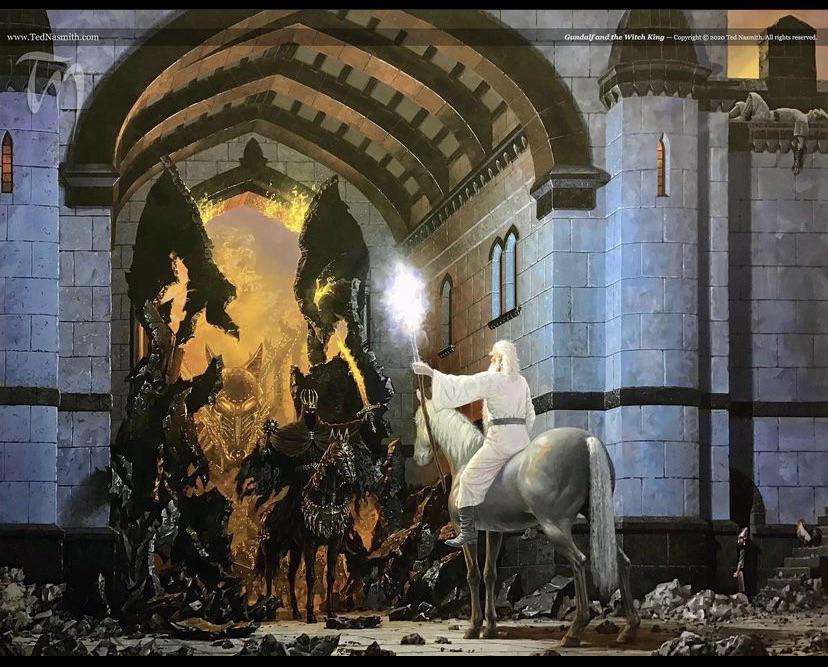

and the person we’ll be eavesdropping on isn’t that loud person on the bus, but the Steward of Gondor, Denethor.

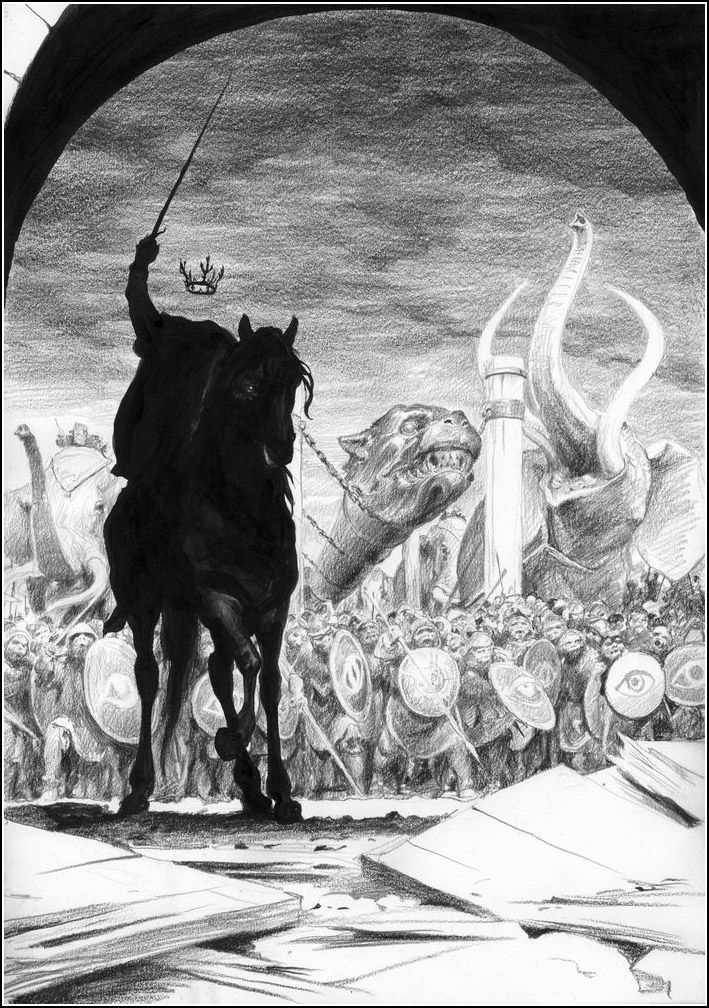

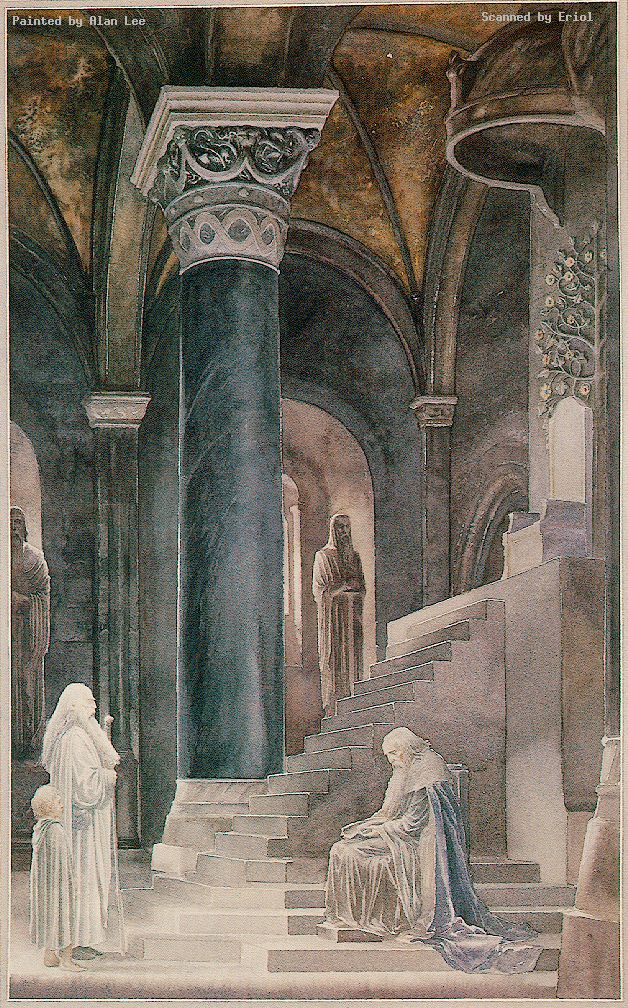

(Alan Lee)

Initially, we don’t know that Denethor has one, of course, although we receive hints in the text—

“ ‘Yea,’ he [Denethor] said; ‘for though the Stones be lost, they say, still the lords of Gondor have keener sight than lesser men…’ “

“ ‘And the Lord Denethor is unlike other men: he sees far. Some say that as he sits alone in his high chamber in the Tower at night, and bends his thought this way and that, he can read somewhat of the future, and that he will at times search even the mind of the Enemy, wrestling with him.’ “ (The Return of the King, Book Five, Chapter 1, “Minas Tirith”)

“But he [Denethor] himself went up alone into the secret room under the summit of the Tower; and many who looked up thither at that time saw a pale light that gleamed and flickered from the narrow windows for a while, and then flashed and went out.” (The Return of the King, Book Five, Chapter 4, “The Siege of Gondor”)

It’s only at Denethor’s end that we see what gleamed and flickered and with what, as Beregond says, he “wrestles” with the Enemy—

(Robert Chronister)

“Then suddenly Denethor laughed. He stood up tall and proud again, and stepping swifly back to the table he lifted from it the pillow on which his head had lain. Then coming to the doorway he drew aside the covering, and lo! he had between his hands a palantir. As he held it up, it seemed to those that looked on that the globe began to glow with an inner flame, so that the lean face of the Lord was lit as with a red fire.” (The Return of the King, Book Five, Chapter 7, “The Pyre of Denethor”)

We don’t, unfortunately, have record of either end of the conversations which Denethor has had, but we know one thing: these were not happy chats—Beregond says, continuing the description above—“And so it is that he is old, worn before his time.”

And it’s not hard to guess another: at the far end of the connection is Sauron, as Gandalf explains to Pippin:

“ ‘Who knows where the lost Stones of Arnor and Gondor now lie buried, or drowned deep? But one at least Sauron must have obtained and mastered to his purposes. I guess that it was the Ithil-stone, for he took Minas Ithil long ago and turned it into an evil place: Minas Morgul, it has become.’ “

We can also guess what has happened to Denethor—exactly what happened to Saruman:

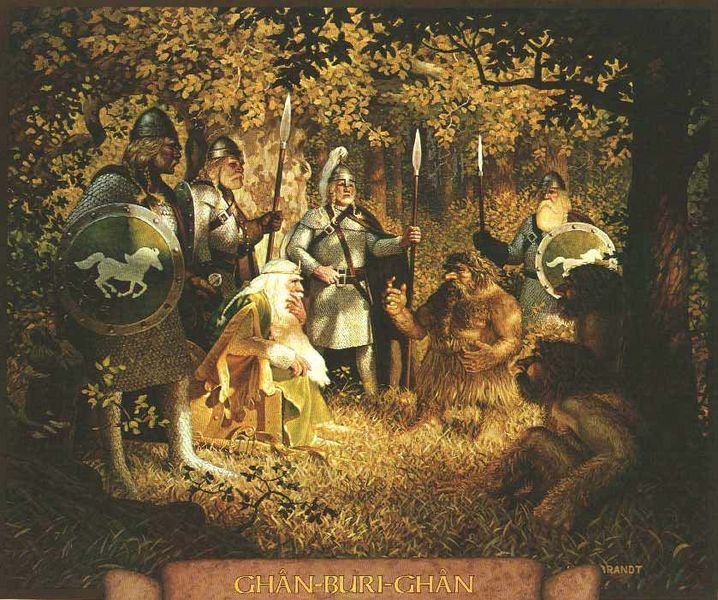

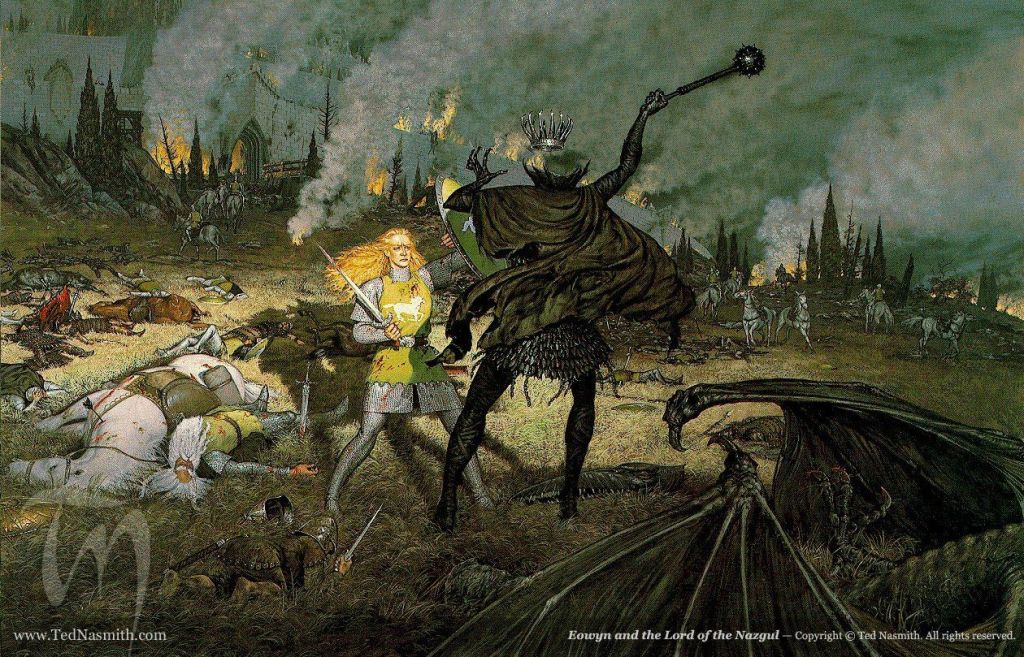

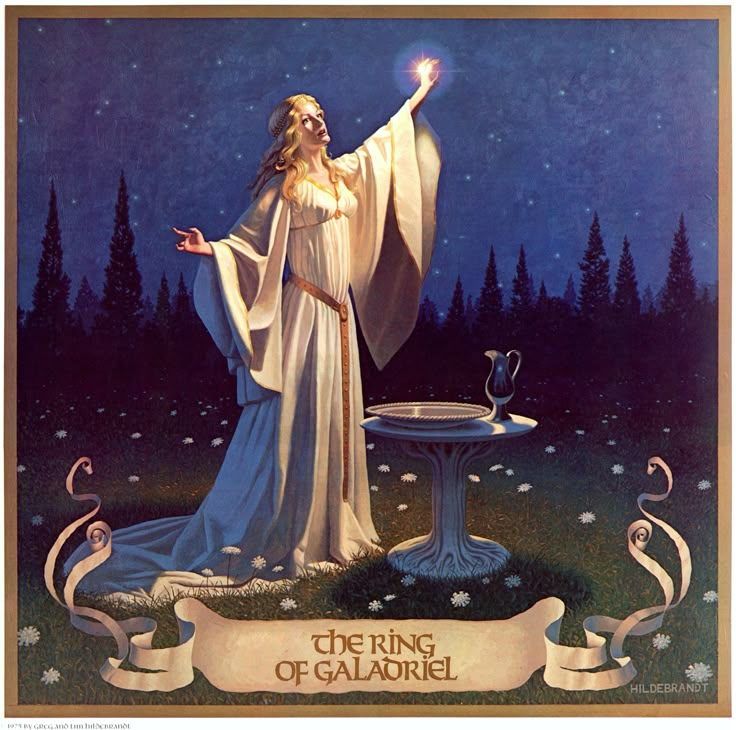

(the Hildebrandts)

“ ‘…yet it seems that he was not content. Further and further abroad he gazed, until he cast his gaze upon Barad-dur. Then he was caught!…Easy it is now to guess how quickly the roving eye of Saruman was trapped and held; and how ever since he has been persuaded from afar, and daunted when persuasion would not serve…How long, I wonder, has he been constrained to come often to his glass for inspection and instruction, and the Orthanc-stone so bent towards Barad-dur that, if any save a will of adamant now looks into it, it will bear his mind and sight swiftly thither?’ “ (The Two Towers, Book Three, Chapter 11, “The Palantir”)

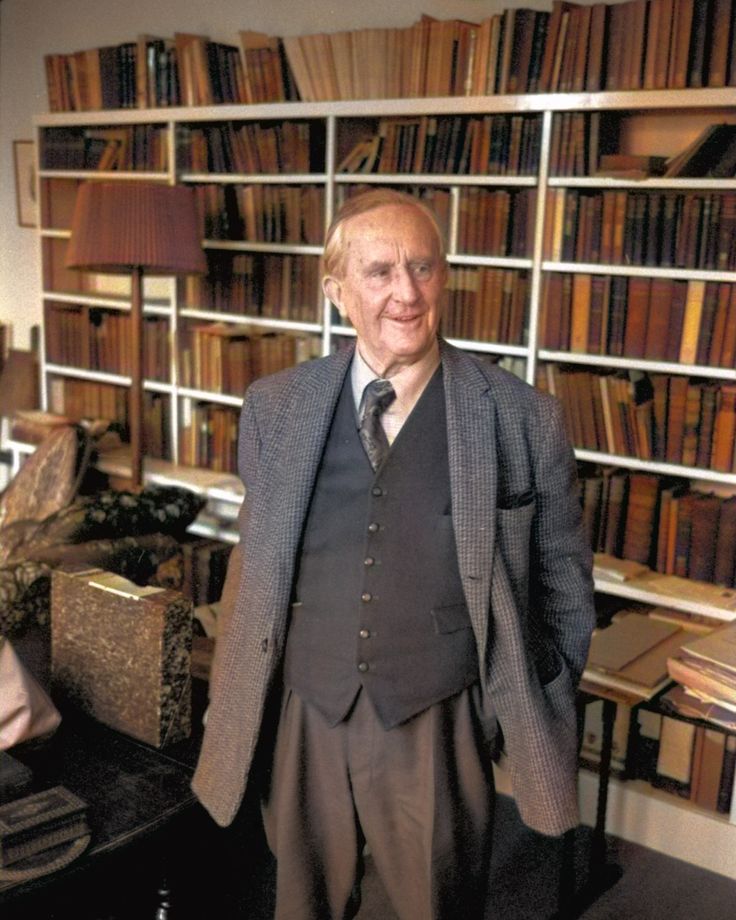

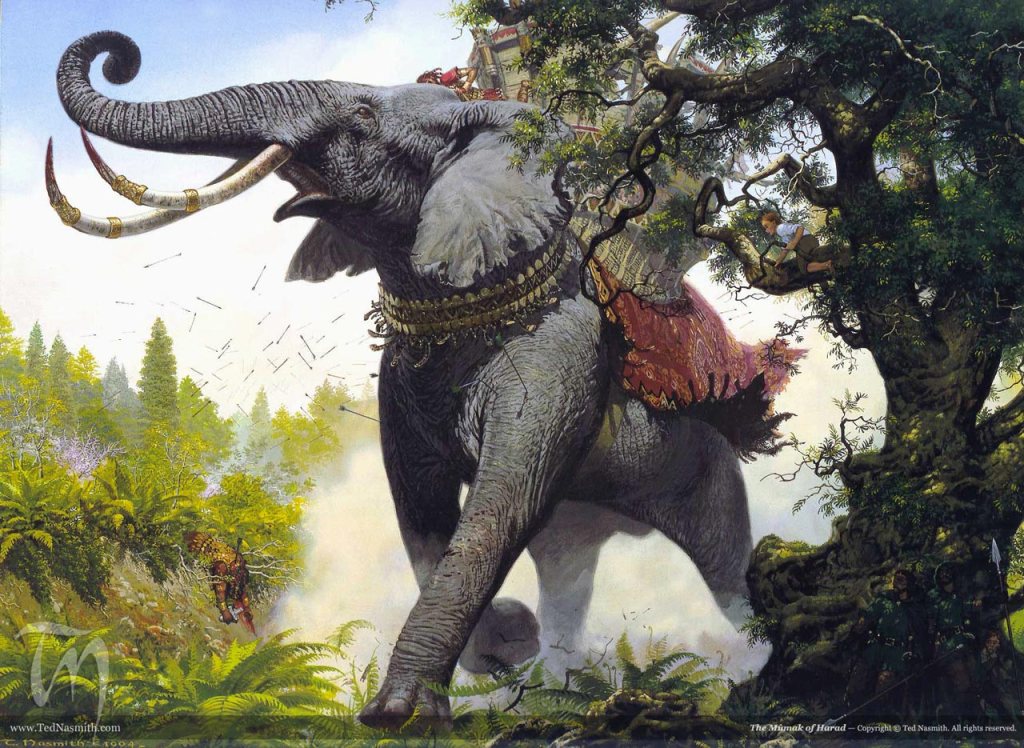

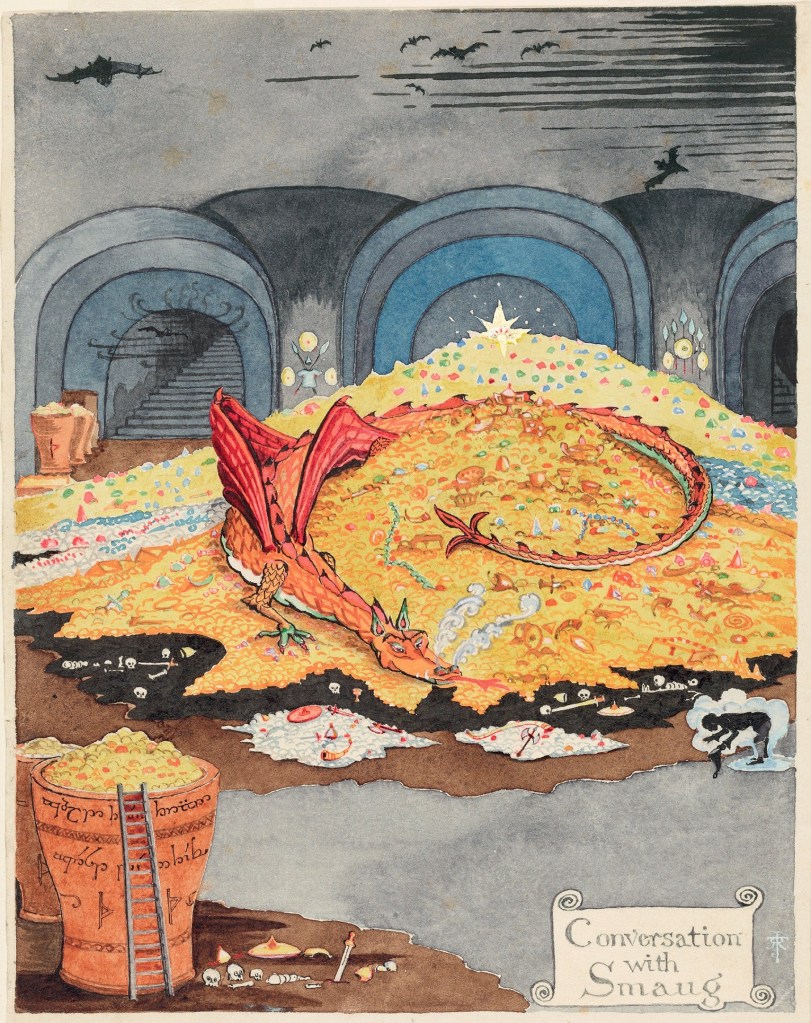

The power of the voice is a strong theme, both in The Hobbit, where we see that Smaug

(JRRT)

can begin to damage Bilbo’s trust in the dwarves with a few words, and in The Lord of the Rings, Saruman’s spy, Grima,

(Alan Lee)

can actually prematurely age Theoden with his talk, sowing, as well, distrust of allies.

Perhaps the most powerful voice is that of Saruman himself, as Gandalf warns Pippin:

“ ‘But there is no knowing what he can do, or may choose to try. A wild beast cornered is not safe to approach. And Saruman has powers you do not guess. Beware of his voice!’ “

(Carl Lundgren)

One example will underline Gandalf’s warning:

“ ‘But my lord of Rohan, am I to be called a murderer, because valiant men have fallen in battle? If you go to war, needlessly, for I did not desire it, then men will be slain…I say, Theoden King: shall we have peace and friendship, you and I? It is ours to command.’ ”

Saruman’s words are simply lies: he began the war when his Orcs marched against Rohan and attacked Helm’s Deep, but his power is as dangerous as Gandalf has warned:

“For many the sound of the voice alone was enough to hold them enthralled; but for those whom it conquered the spell endured when they were away, and ever they heard that soft voice whispering and urging them. But none were unmoved; none rejected its pleas and its commands without an effort of mind and will, so long as its master had control of it.” (The Two Towers, Book Three, Chapter 10, “The Voice of Saruman”)

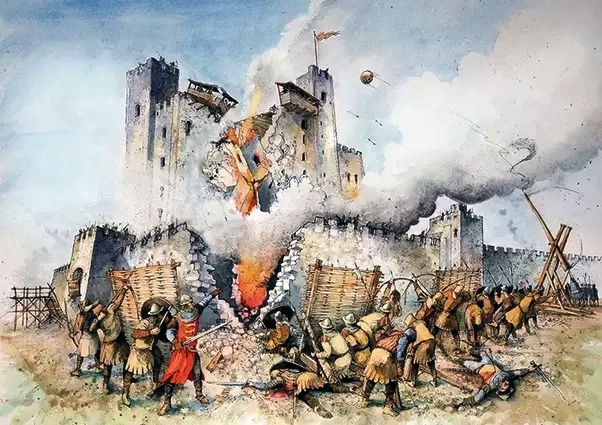

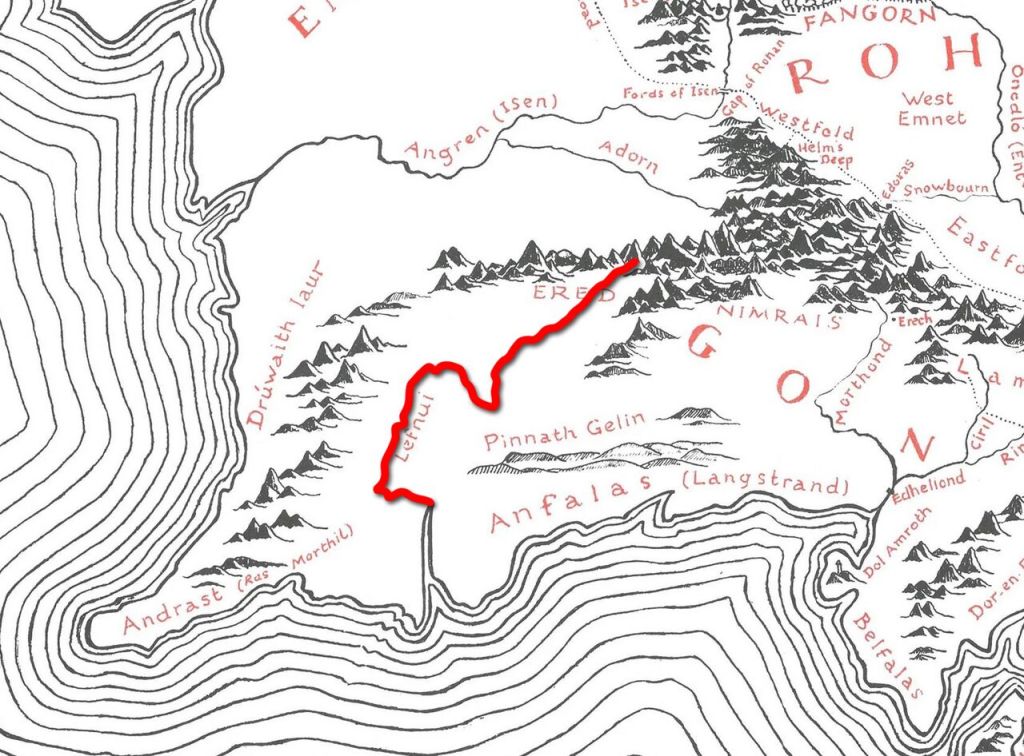

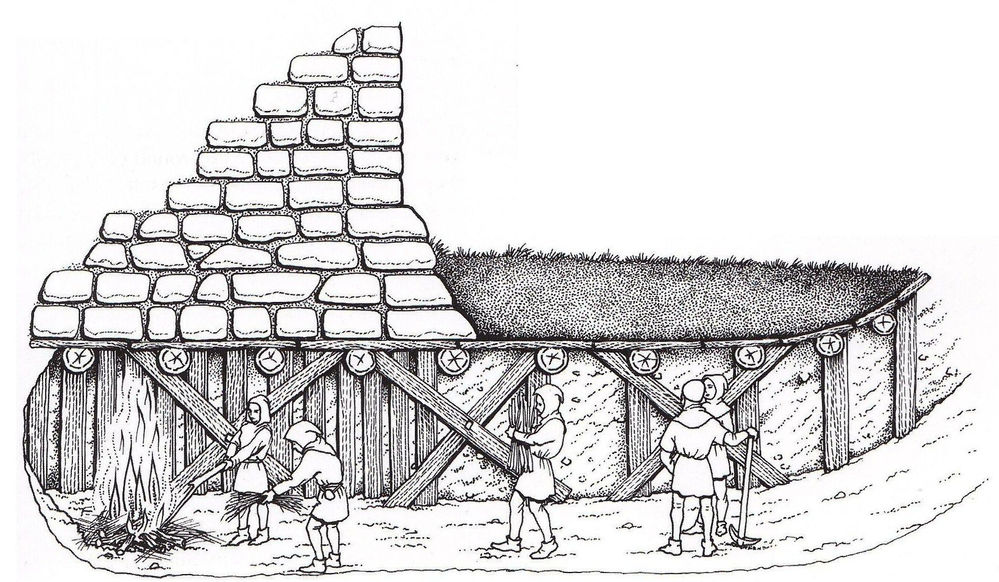

The few words we actually hear from Sauron are brief questions and commands, but, at least initially, these wouldn’t have come to control as powerful a personality as Denethor, so I’m imagining something more like Saruman, but, judging from Denethor’s reactions to others, this included the kind of undermining which Smaug and Grima practice.

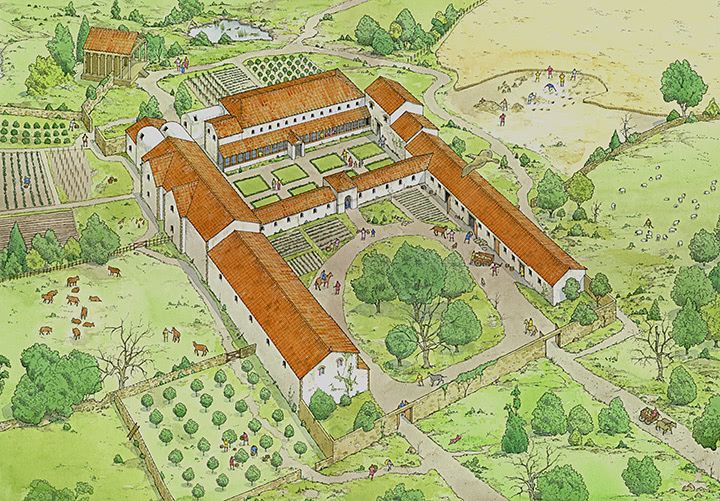

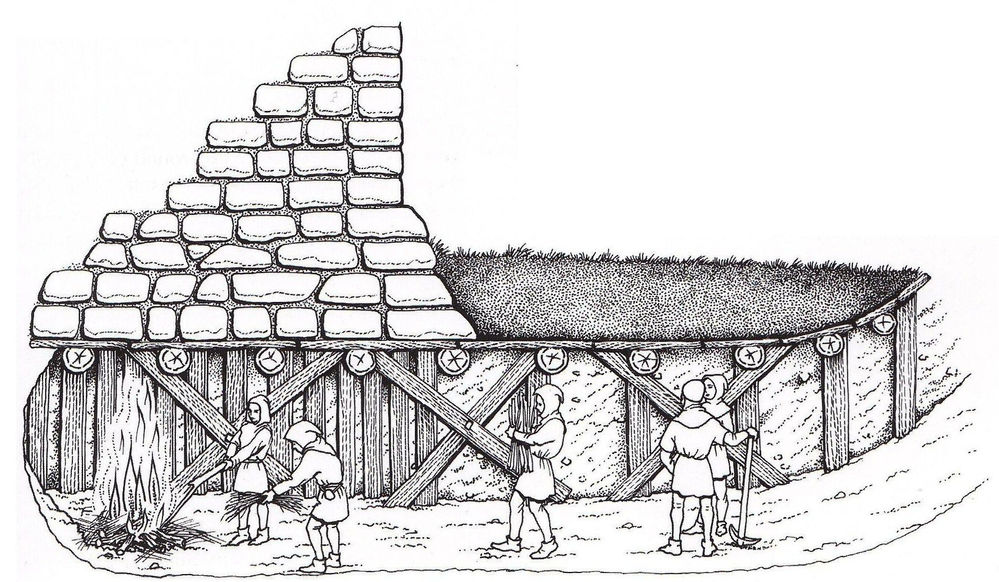

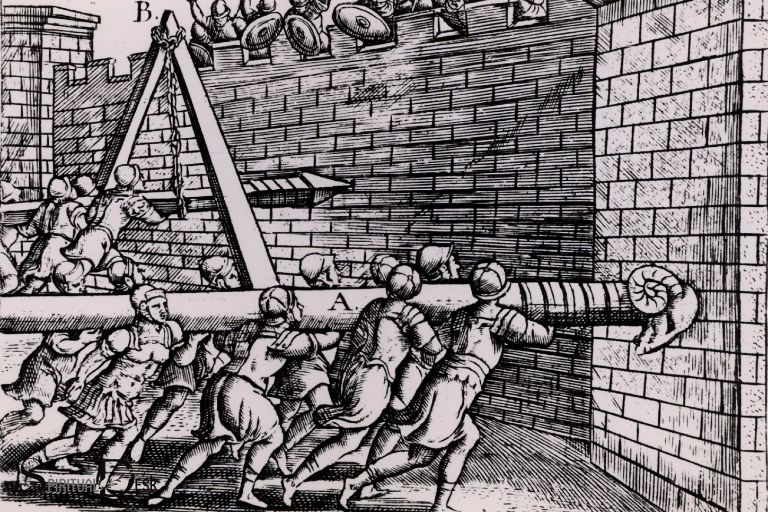

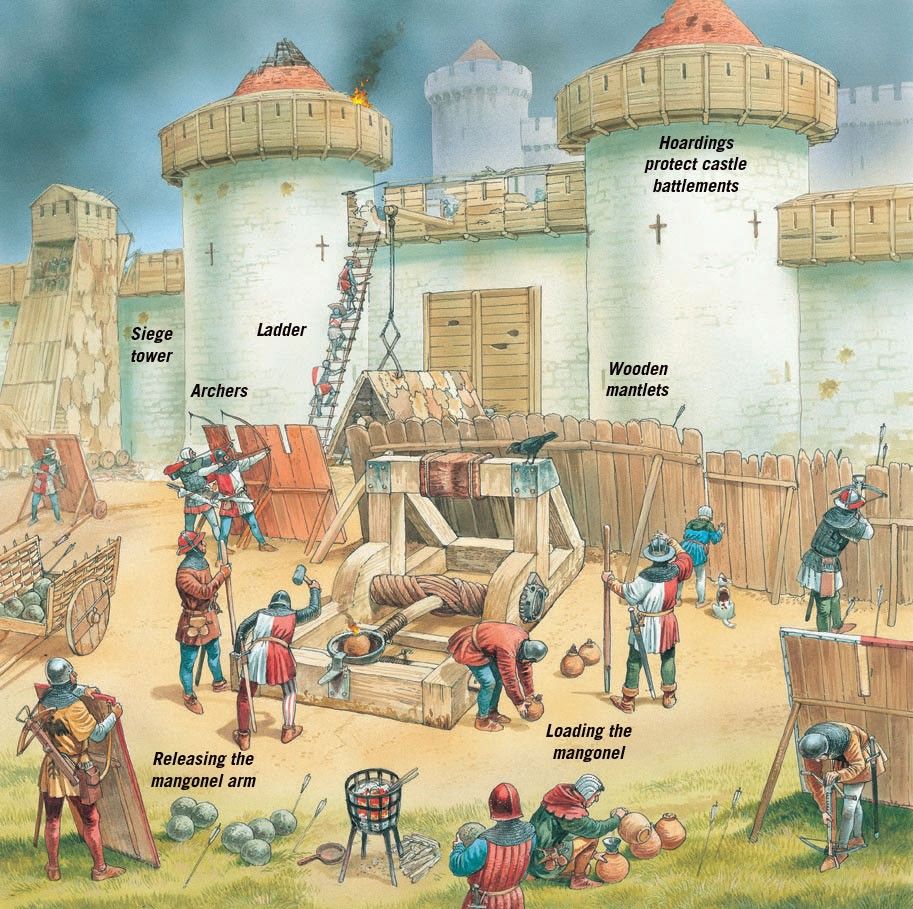

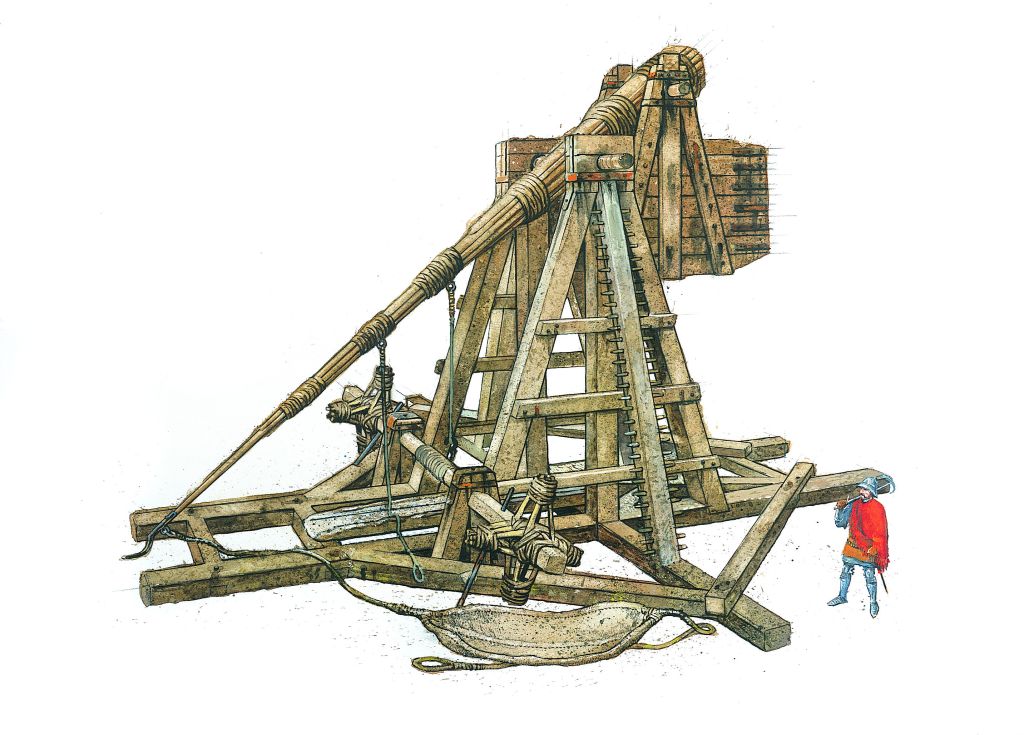

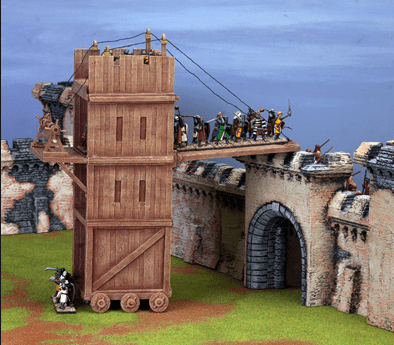

(This is medieval undermining, and shows one of two possibilities. The first is to dig all the way under a castle wall and burst out suddenly behind the defenders. The second, shown here, is to dig under the way, replace the foundations with wooden props, then set fire to the props in hopes that, without them, the wall will crumble. The illustration is from the site “Classroom Adventures” and I recommend the essay which is attached to the illustration as a very useful way of getting up to speed on how medieval sieges—like that of Minas Tirith—were conducted: https://www.classroomadventures.co.uk/post/under-siege-a-history-of-siege-weaponshttps://www.classroomadventures.co.uk/post/under-siege-a-history-of-siege-weapons )

This posting had a different title, when I began it: “Sauron Psychologist” and, in Denethor’s reactions, it would appear that Denethor has been attacked on two main fronts: jealousy and insecurity, suggesting that, in his conversations with the Steward, Sauron has learned just where Denethor’s psychological vulnerabilities lie.

Although Denethor favors Boromir, he seems more than a little anxious at Faramir’s attraction to Gandalf, as Denethor says bitterly:

“ ‘See, you have spoken skillfully, as ever; but I, have I not seen your eyes fixed on Mithrandir, seeking whether you said well or too much? He has long had your heart in his keeping…For Boromir was loyal to me and no wizard’s pupil.” (The Return of the King, Book Five, Chapter 4, “The Siege of Gondor”)

Sauron also appears to have worked to undermine Denethor’s understanding of his role in Gondor. He is, after all, not the King, but the King’s lieutenant. His family has ruled in place of the King for so long, however, that Denethor seems—I think that we can assume with Sauron’s encouragement– to have made the assumption that he is the King:

“ ‘I will not step down to be the dotard chamberlain of an upstart. Even were his claim proved to me, still he comes but of the line of Isildur. I will not bow to such a one, last of a ragged house long bereft of lordship and dignity.’ “

And I would suggest that, just as Gandalf, long before, has said that the beginning of Saruman’s attempt to persuade him in Orthanc had seemed “as if he were making a speech long rehearsed”, so Denethor’s reply to Gandalf’s question “What then would you have…if your will could have its way?” has that same ring, and is just as false:

“ ‘I would have things as they were in all the days of my life…and in the days of my longfathers before: to be the Lord of this City in peace, and leave my chair to a son after me, who would be his own master and no wizard’s pupil. But if doom denies this to me, then I will have naught: neither life diminished, nor love halved, nor honour abated.’ “(The Return of the King, Book Five, Chapter 7, “The Pyre of Denethor”)

Without Sauron’s actual words, this can only be a guess, but I wonder if, behind all of this is Sauron’s “whispering and urging”, saying things like: “You once had two sons, but your favorite died on a mission which failed, and the other is no longer yours, is he? A wizard’s pupil now, and you fear, but know, this. And will the pupil ever become master, or will his master become master of all? Without the interference of wizards, we could have had peace, you and I—it was in our power—two wise rulers sharing Middle-earth—I the East, you the West, for no King would ever return—should ever return—to take your place, in Gondor. But now”—and here I switch from my text to JRRT’s–‘For a little space you may triumph on the field, for a day. But against the Power that now arises there is no victory. To this City only the first finger of its hand has yet been stretched. All the East is moving. And even now the wind of thy hope cheats thee and wafts up the Anduin a fleet with black sails. The West has failed. It is time for all to depart who would not be slaves.’ “

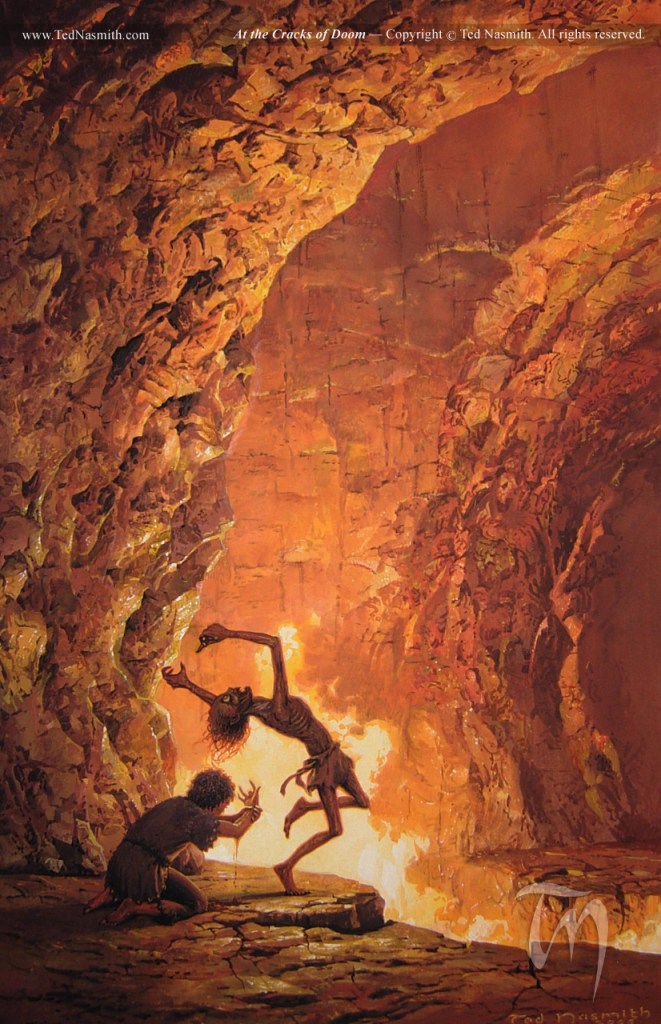

Smaug ultimately didn’t convince Bilbo. Gandalf freed Theoden from Grima’s attempt at senescence. Theoden’s mockery of Saruman broke the spell of Saruman’s voice. But there was no rescue for Denethor:

“Then Denethor leaped upon the table; and standing there wreathed in fire and smoke he took up the staff of his stewardship and broke it on his knee. Casting the pieces into the blaze he bowed and laid himself on the table, clasping the palantir with both hands upon his breast. And it was said that ever after, if any man looked in that Stone, unless he had a great strength of will to turn it to other purpose, he saw only two aged hands withering in flame.” (The Return of the King, Book Five, Chapter 7, “The Pyre of Denethor”)

Thanks, as always, for reading.

Stay well,

Noise-canceling earphones definitely have their merits,

But avoid crystal balls at all costs,

Though remembering that, as always, there’s

MTCIDC

O