Tags

Chronology, crannogs, Durin's Day, John Bauer, Laketown, Loch Tay, Lonely Mountain, Mirkwood, passing time, Scotland, Smaug, Ted Nasmith, The Hobbit, The Lord of the Rings, Thorin, Thror's Map, Tolkien

As always, dear readers, welcome.

Some years ago, we visited the Strong National Museum of Play, in Rochester, New York. (Highly recommended!)

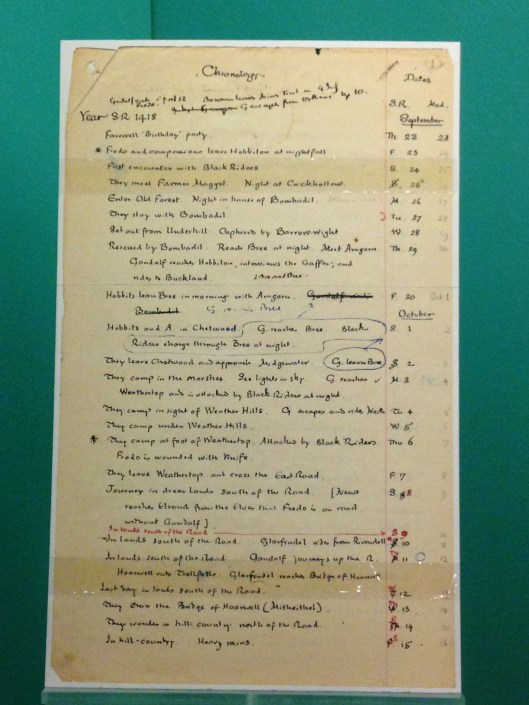

There, we had found this in one of the display cases–

It’s a reproduction of the first page of a chronology of The Lord of the Rings by JRRT, covering the end of September and the beginning of October of SR1418, from the Marquette University collection. Looking closely we could see just how detailed it was and, recently, we looked at the page again and it made us wonder just how visible such detailing was in the actual work: do we really see each day portrayed? Are there moments when days—or more—go by unmarked? If so, when? And why?

To answer our questions, we turned first to The Hobbit, as a kind of test case, and, in our last posting, had, by the end, reached the western edge of Mirkwood.

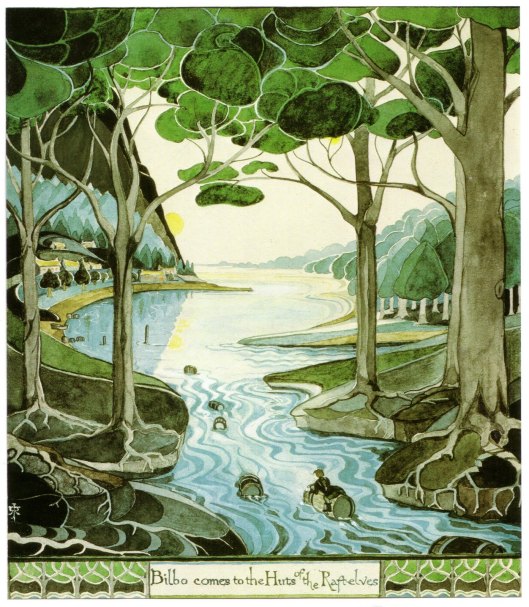

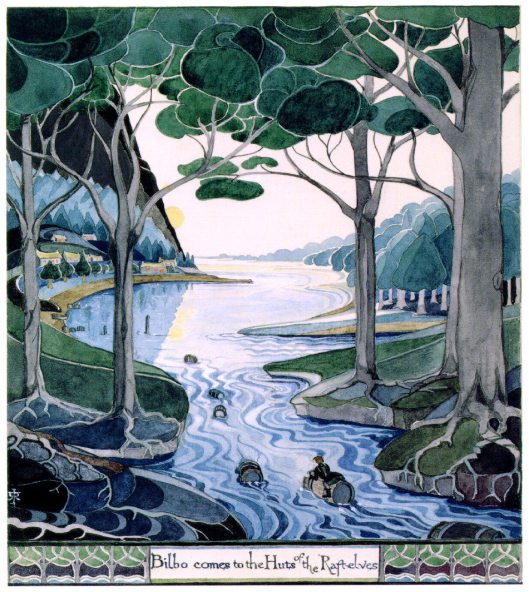

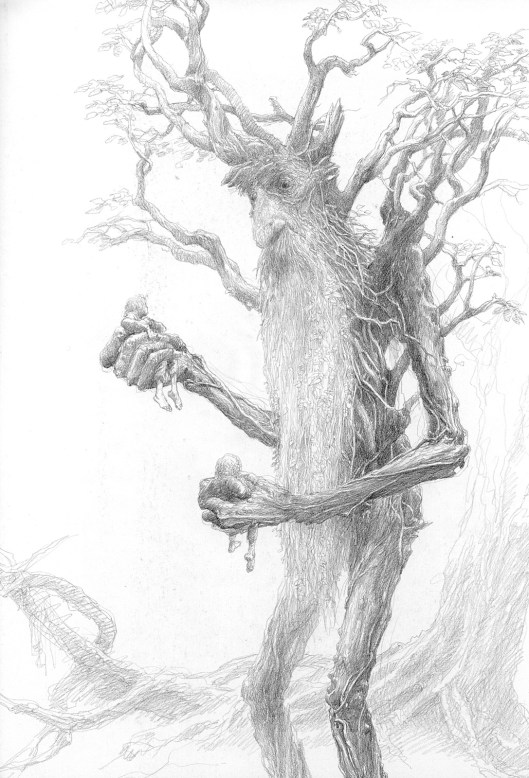

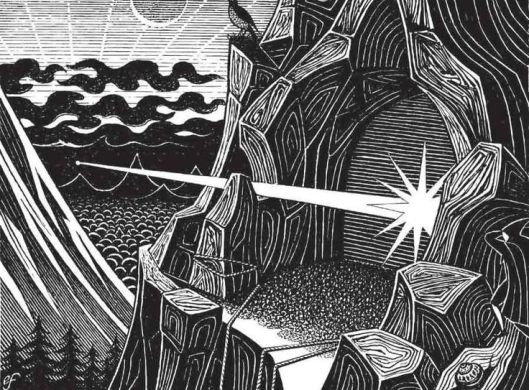

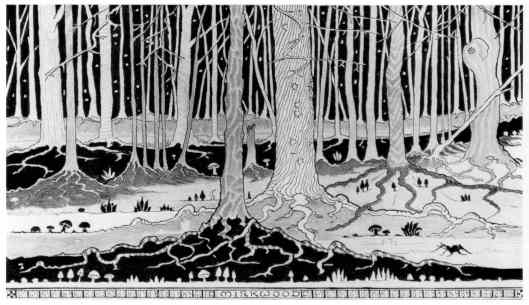

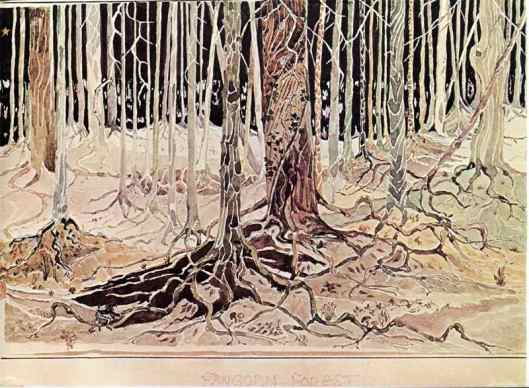

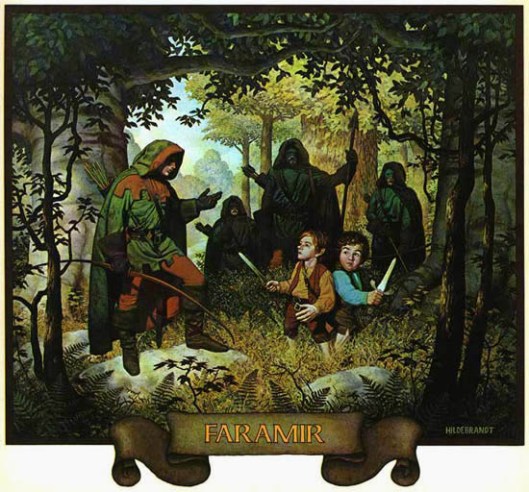

This, as the caption says, is a work by Ted Nasmith, one of our favorite Tolkien illustrators, but here’s JRRT’s version.

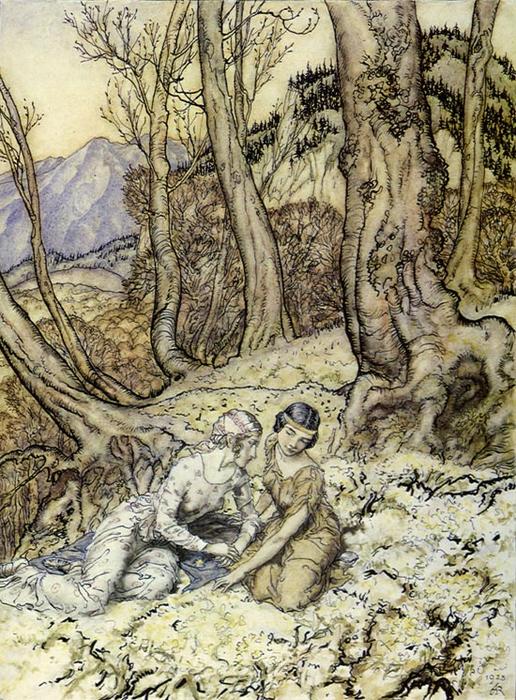

(As we’ve pointed out some time ago, Tolkien’s version would appear to owe something to the work of the early-20th-century Swedish illustrator, John Bauer (1882-1918).)

As Gandalf waves a good-bye and shouts a final warning, the company plunges in—and immediately time seems to blur:

“All this went on for what seemed to the hobbit ages upon ages…days followed days, and still the forest seemed just the same…” (The Hobbit, Chapter 8, “Flies and Spiders”)

They reach a dangerous stream, one of their company falls in—and immediately drops into a deep sleep, forcing them to carry him as they move away from the stream and, although their journeying continues to seem endless:

“About four days from the enchanted stream they came to a part where most of the trees were beeches…A few leaves came rustling down to remind them that outside autumn was coming on…Two days later they found their path going downwards.”

Soon after that, Bilbo is sent up a tree to see where they are—and, it appears the next day they are tormented by visions of feasting elves. The next morning? the scattered dwarves and Bilbo are attacked by outsized spiders.

As we said, this is all rather blurry—not many time words are used and, like the forest itself, the passage of time appears almost featureless. In the confusion around the elvish torment and the spiders, however, Thorin has disappeared, only to be made captive by those very elves and taken to the palace of their king.

And then time moves forward—a little: “The day after the battle with the spiders Bilbo and the dwarves made one last despairing effort to find a way out before they died of hunger and thirst…Such day as there ever was in the forest was fading once more into the blackness of night, when suddenly out sprang the light of many torches all round them…” (The Hobbit, Chapter 9, “Barrels Out of Bond”)

The other dwarves are captured by the elves, but Bilbo, using his ring, escapes–and then manages to slip into the elves’ underground world—and into what appears to be another nearly-timeless place:

“Poor Mr. Baggins—it was a weary long time that he lived in that place all alone…Eventually, after a week or two of this sneaking sort of life, by watching and following the guards and taking what chances he could, he managed to find out where each dwarf was kept.

He found all their twelve cells in different parts of the palace, and after a time he got to know his way about very well.”

The chance discovery of the use of an underground stream as a method of shipping goods—and wine in particular—provides Bilbo with the final means to escape the elves, but how long does all of this, from the capture of the dwarves to that escape, take?

“For some time Bilbo sat and thought about this water-gate, and wondered if it could be used for the escape of his friends, and at last he had the desperate beginnings of a plan.”

If you are familiar with the story, you know that the plan entails escaping in barrels,

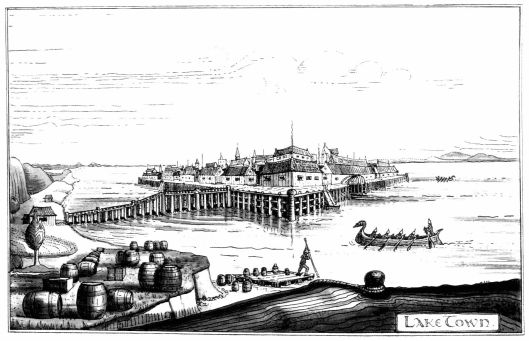

bobbing and rolling all night down the river till they were snagged and collected and, the next morning, moved on towards Lake-town, which they reached in the evening (“The sun had set when turning with another sweep towards the East the forest-river rushed into the Long Lake.”).

(This reminds us to mention crannogs—lake houses—of which there is a very convincing reconstruction on Loch Tay, in Scotland. Here’s a LINK if you’d like to know more.)

The dwarves and Bilbo had stayed in Lake-town two weeks when: “At the end of a fortnight Thorin began to think of departure.” (The Hobbit, Chapter 10, “A Warm Welcome”) When they actually departed, however, is unclear: “So one day, although autumn was now getting far on, and winds were cold, and leaves were falling fast, three large boats left Lake-town, laden with rowers, dwarves, Mr. Baggins, and many provisions.”

They land “On the Doorstep” (the title of Chapter 11) of the Lonely Mountain. It has taken them three days to get there by boat. (“In two days going they rowed right up the Long Lake and passed out into the River Running…At the end of the third day, some miles up the river, they drew in to the left or western bank and disembarked.” The Hobbit, Chapter 11, “On the Doorstep”)

But how long do they spend on that doorstep?

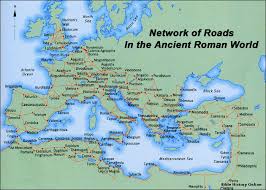

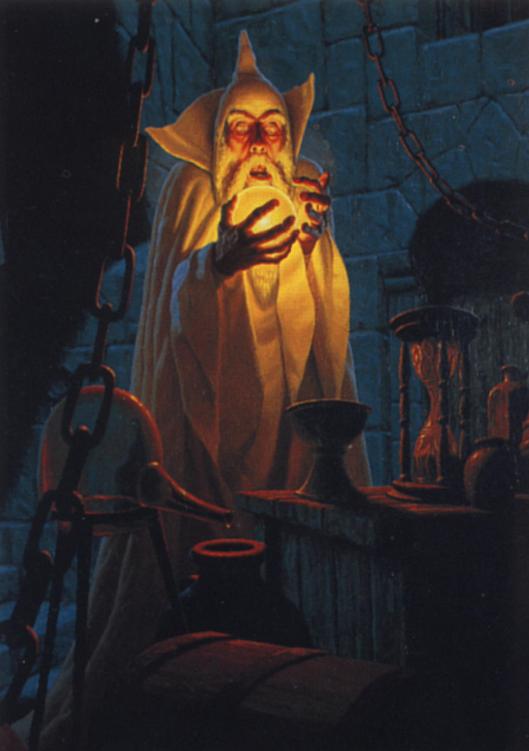

We know, from Elrond’s reading of the moon runes on Thror’s map, that there is a kind of deadline:

“Stand by the grey stone when the thrush knocks…and the setting sun with the last light of Durin’s Day will shine upon the key-hole.” (The Hobbit, Chapter 3, “A Short Rest”)

Thorin himself is hard-pressed to say exactly what day this is, but the dwarves and hobbit continue their journey to find the hidden back door.

After camping where their supplies have been left, they begin their actual explorations the next day. (“They spent a cold and lonely night…The next day they set out again.”) Bilbo and several of the dwarves make a brief expedition to the front door and back, seemingly within a day.

We now enter into another blurry period, for, as the dwarves and Bilbo search for the hidden door, all we read is “day by day they came back to their camp without success” until: “ ‘Tomorrow begins the last week of autumn,’ said Thorin one day.” And the next day—which is, in fact, the Durin’s Day of the map—they find and open the door.

Thorin sends Bilbo down into the dark, which, we presume takes some time because we are told that “It was midnight and clouds had covered the stars” when Balin carried him out. (The Hobbit, Chapter 12, “Inside Information”) He has taken a cup from Smaug’s hoard, however, and this rouses the dragon, forcing the dwarves to take shelter in the tunnel within the hidden door where they remain as Bilbo returns a second time—the next day—to visit Smaug again. (“The sun was shining as he started…”) That same day, they take shelter within the tunnel and Smaug seals them in.

How long they are sealed in isn’t initially clear: “They could not count the passing of time…At last after days and days of waiting” Chapter 13 begins, but, with the addition of “as it seemed”, suggesting that not much time—perhaps even only hours—had actually passed. (The Hobbit, Chapter 13, “Not at Home”). This is made clearer, however, when we are told: “As a matter of fact two nights and the day between had gone by…since the dragon smashed the magic door…”). After Bilbo makes another foray—followed by the others—down into Smaug’s lair, they find it empty, press beyond it, and, eventually, the same day, move their camp to an old watchpost on the southwest corner of the mountain.

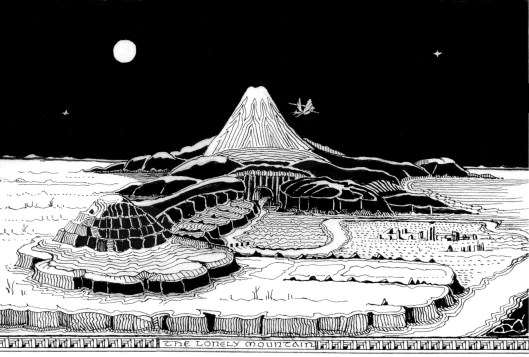

(We presume that the post is at the left-hand edge of this JRRT illustration.)

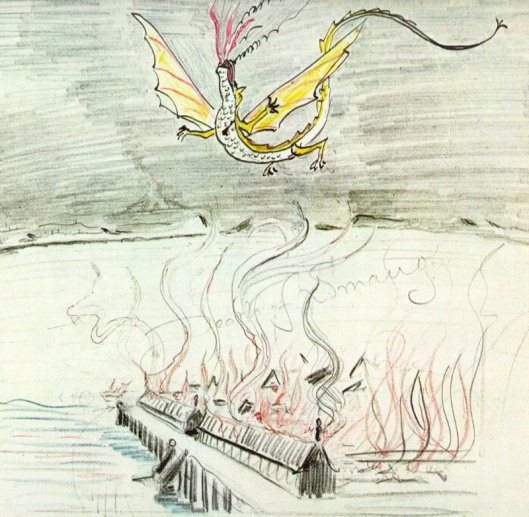

Smaug, of course, has gone off to destroy Lake-town and is killed there

and soon a combined force of forest elves and men from the ruined Lake-town set off for the Lonely Mountain (“It was thus that in eleven days from the ruin of the town the head of their host passed the rock-gates at the end of the lake and came into the desolate lands.” The Hobbit, Chapter 14, “Fire and Water”)

The narrative then moves back once more to the dwarves, who, by means of an ancient raven, have heard what is approaching and begin to fortify the main door of the Mountain when: “There came a night when suddenly there were many lights as of fires and torches away south in Dale before them.” (The Hobbit, Chapter 15, “The Gathering of the Clouds”) Presumably, this is some days after the invaders have reached the desolate lands, though how many is not said, but, “The next morning early a company of spearmen was seen crossing the river…”

Thus begins the last big event in The Hobbit: the siege of the Mountain by elves and men and the following Battle of the Five Armies. With the arrival of the besiegers and the stalemate caused by Thorin’s stubbornness, time is blurred once more: “Now the days passed slowly and wearily.” (The Hobbit, Chapter 16, “A Thief in the Night”) It is suddenly marked, however, by news:

“Things had gone on like this for some time, when the ravens brought news that Dain and more than five hundred dwarves…were now about two days’ march of Dale…”

This sparks Bilbo into attempting to use the Arkenstone as a bargaining chip and “Next day trumpets rang early in the camp” (The Hobbit, Chapter 17, “The Clouds Burst”) as the allies try to deal with Thorin and here we see time, from being blurred, begins to be more clearly stated: after the “for some time”, we see “the next morning” and then, with the parley discouraged by dwarvish arrows, “That day passed and then the night” and, that following day, everything falls apart: Goblins and Wild Wolves appear and the allies, Dain and his Iron Mountain dwarves, and Thorin & Co, are all involved in a massive struggle which only ends when the Eagles arrive—and Beorn–, Bilbo is knocked unconscious, and Thorin is mortally wounded.

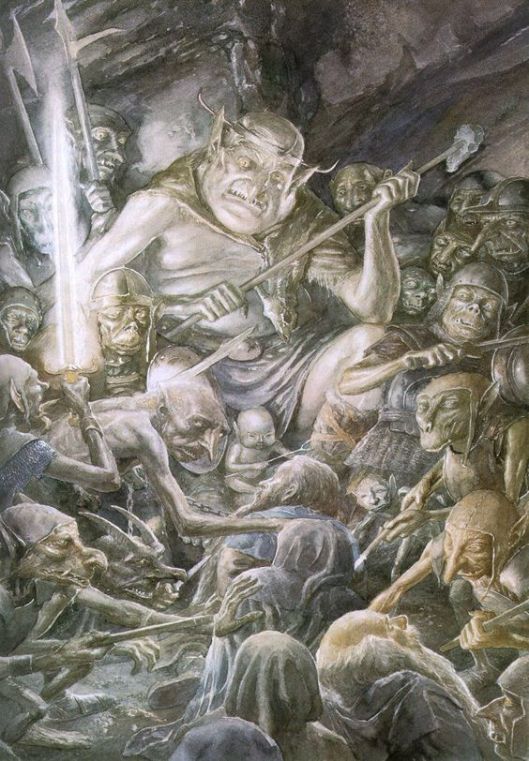

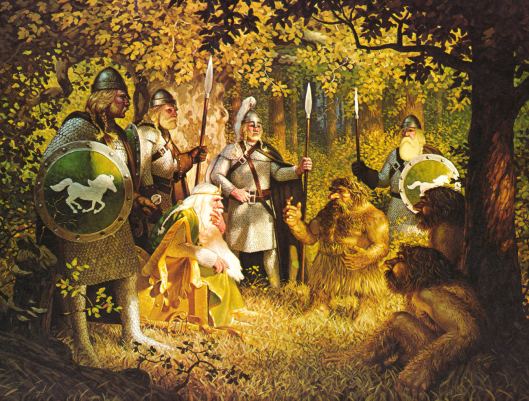

(This is by Justin Gerard—here’s a LINK to a really interesting website dedicated to fantasy illustration where we found it.)

The story hasn’t ended, however, though time goes back into its biggest blur yet. The dragon dead, the Mountain recovered by the dwarves, Bilbo “started on his long road home” . Long it is, as “by mid-winter Gandalf and Bilbo had come all the way back…to the doors of Beorn’s house: and there for a while they both stayed…It was spring, and a fair one with mild weathers and a bright sun, before Bilbo and Gandalf took their leave at last of Beorn…” (The Hobbit, Chapter 18, “The Return Journey”) We see them reach Elrond’s Last Homely House “on May the First”, though “after a week…[Bilbo and Gandalf] said farewell to Elrond” (The Hobbit, Chapter 19, “The Last Stage”). It is June, however, while the two are still on their journey (“for now June brought summer”) and, in fact, we are told that it is precisely the 22nd of June that they arrive at Bag End, as, on that day, “Messrs Grubb, Grubb, and Burrowes” are about to auction off “the effects of the late Bilbo Baggins, Esquire”.

The book goes on a little further, into Bilbo’s future, but this seems like a good place for us to end this posting. What have we discovered with our investigation? We guess we would say that, in The Hobbit, time comes in two forms:

- there is passing time—those blurs when people are traveling or waiting—this can be simply marked as time passing, or it may be described in weeks

- there is slowed time—this is around important events in the narrative and is always specific to days

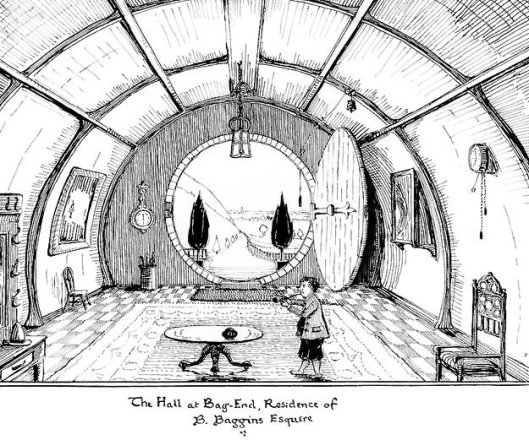

And, unless one keeps a very detailed journal

perhaps this can be seen as a kind of imitation of everyone’s life: long stretches of just “doing things” broken up by short patches of intense, memorable activity. What do you think, readers?

And, while you’re thinking, thanks for reading.

MTCIDC

CD

)

)