Tags

Al Capone, Christopher Tolkien, dictators, Edward VIII, Galadriel, gang, George V, George VI, King Edward VII, Monarchy, oligarchy, Queen Elizabeth II, Queen Victoria, Rivendell, Saruman, Sharkey, Shire government, The Lord of the Rings, Thranduil, Tolkien

Welcome, as ever, dear readers.

In a letter to his son, Christopher, of 29 November, 1943, Tolkien wrote:

“Give me a king whose chief interest in life is stamps, railways, or race-horses; and who has the power to sack his Vizier (or whatever you care to call him) if he does not like the cut of his trousers. And so on down the line. But, of course, the fatal weakness of all that—after all only the fatal weakness of all good natural things in a bad corrupt unnatural world—is that it works and has worked only when all the world is messing along in the same good old inefficient human way.” (Letters, 64)

Monarchs, of course, are all that he had known, when it came to heads of state. Born during the last years of Queen Victoria (ruled 1837-1901),

he lived under King Edward VII (reigned 1901-1910),

George V (ruled 1910-1936),

Edward VIII (ruled 1936—abdicated in favor of his younger brother),

George VI (ruled 1936-1952),

and died in 1973 during the reign of Elizabeth II (1952—the present).

It’s not that he was very enthusiastic about monarchies—in the same letter he says “My political opinions lean more and more to Anarchy (philosophically understood, meaning abolition of control not whiskered men with bombs)…”

but even there he couldn’t escape the structure he was a subject of, adding “or to ‘unconstitutional’ Monarchy.”

This made us consider how this conditioning might be reflected in Middle-earth—after all, the title of the third volume of The Lord of the Rings is The Return of the King. What were the governments of Middle-earth at, roughly, the time of the War of the Ring? How many were monarchies and what other forms might there be?

Recently, we had looked at the governing structure of the Shire,

about which, as JRRT has told us:

“The Shire at this time had hardly any ‘government’. (The Lord of the Rings, Prologue, 3. “Of the Ordering of the Shire”)

This depends, of course, upon what is meant by “government”. There is an elected Mayor, the “only real official in the Shire”, and whose job appears, at first, to be only ceremonial, until we are informed that “the offices of Postmaster and First Shirriff were attached to the mayoralty.” At the same time, there was an hereditary position of leader, the Thain, controlled by the Took family, and, the more Tolkien explains, the more it appears that what really governs the Shire is an oligarchy—that is, a small group of families who, together, quietly run things. (There may also be tension just below the surface about which families this oligarchy includes. When Saruman (aka “Sharkey”) takes over the Shire, he favors not the Tooks, but the Bagginses, suggesting that he is aware of this tension and may be exploiting it.)

As we move across Middle-earth with the Fellowship,

the next settlement we come to is Bree. The government of this is completely unclear. All that we’re told is that:

“The Big Folk and the Little Folk (as they called one another) were on friendly terms, minding their own affairs in their own ways, but both rightly regarding themselves as necessary parts of the Bree-folk…The Bree-folk, Big and Little, did not themselves travel much, and the affairs of the four villages were their chief concern.” (The Fellowship of the Ring, Book One, Chapter 9, “At the Sign of the Prancing Pony”)

Their only defense appears to have been “a deep dike [ditch] with a thick hedge on the inner side”, but who maintains it is not mentioned, although there is a gate guard—the evil Bill Ferny, when the hobbits first approach the gate. Unlike the Shirriffs of the Shire, however, we have no idea what structure might lie behind this position.

As we travel farther eastward, we come to Rivendell.

Here, Elrond is clearly in charge, but seems to have no distinct title—unlike Thranduil, who is called “the King of the Elves of Northern Mirkwood” (The Fellowship of the Ring, Book Two, Chapter 2, “The Council of Elrond”). The same lack of title seems to be true of Galadriel.

Although Gimli calls her “Queen Galadriel” (The Two Towers, Book Three, Chapter 8, “The Road to Isengard”), and she, along with Celeborn, rules Lorien, she does not bear that title—in fact she may be a little anxious about it, as seen when Frodo offers her the ring:

“You will give me the Ring freely? In place of the Dark Lord you will set up a Queen.” (The Fellowship of the Ring, Book Two, Chapter 7, “The Mirror of Galadriel”)

Along with Frodo’s frightening vision of her, this seems more like a warning than a statement.

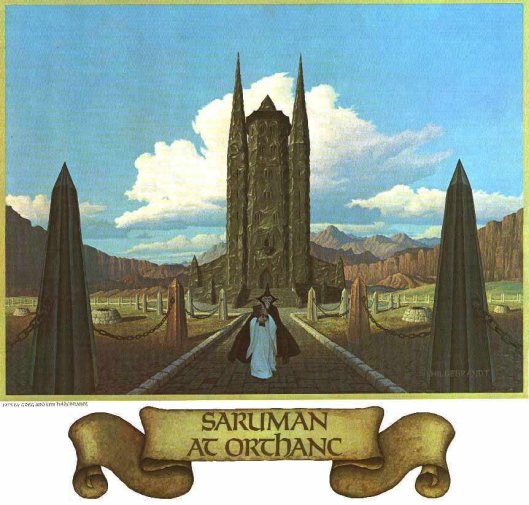

We’ve seen that monarchy seems to be linked with inheritance: the thainship in the Shire is passed down through the Tooks. Even Elrond and Galadriel appear to hold their positions through seniority. In our next government, it is self-assumed, as Saruman, once referred to by Gandalf as “the chief of my order” (The Fellowship of the Ring, Book One, Chapter 2, “The Shadow of the Past”), begins to have grander plans.

In contrast to other monarchs in The Lord of the Rings, Saruman, we would suggest, is not so much a medieval king, as others in Middle-earth are, but an avatar for modern (1930s-1940s) dictators,

with, as Treebeard says, “a mind of metal and wheels” (The Two Towers, Book Three, Chapter 4, “Treebeard”). In fact, Saruman is a relative newcomer to the business, “setting up on his own with his filthy white badges”, as Grishnakh describes him (The Two Towers, Book Three, Chapter 3, “The Uruk-hai”), in contrast with Sauron, who, although intermittent in his attempts at control, has been involved in the process in Middle-earth for many centuries.

In his role of metal and wheels dictator, Saruman turns Isengard into a factory/fortress, manufacturing everything from orcs to swords within its precinct. His orc captain, Ugluk, calls him “Saruman the Wise, the White Hand”, but we see him later in his real form, as he works to destroy the Shire, as “Sharkey”—a name he says “All my people used to call me that in Isengard, I believe. A sign of affection, possibly.” (The Return of the King, Book Six, Chapter 8, “The Scouring of the Shire”) This is hardly “His Majesty”. Rather, it’s more like the kind of nickname a gang-leader in the US in the 1920s-30s might have had, like “Scarface” Al Capone.

“Sharkey” may be derived, as JRRT suggests, from “Orkish…sharku, ‘old man’,” but it also suggests a fishy predator—a very appropriate image for a would-be dictator.

In our next, we’ll answer Grishnakh’s question: “Is Saruman the master or the Great Eye?” as we continue our exploration of government in Middle-earth.

Thanks, as always, for reading.

MTCIDC

CD