Welcome, dear readers, as always!

In this posting, we want to think out loud about something which has puzzled us for some time. Regular readers must know by this time that, along with literature of various times and places, we’re also very much interested in world history, from its human beginnings all the way up to the present. As those of you who have read past postings know, we have sometimes tried to apply our interest (and, we hope our knowledge) to the works of one of our favorite fantasy authors, JRR Tolkien. In our last posting, for example, we have spent a little time considering the 20th-century world of dictators and how they might have influenced JRRT’s depiction of Sauron and his plans.

In this posting, we want to look at something we’ve touched upon some time in the past, the economic/social structure of Middle Earth (or Middle-earth as it sometimes seems to appear). After all, kingdoms don’t just magically appear and survive: or, in Middle Earth, do they? For fun, we wondered what we might find in The Lord of the Rings which would remind us of our own Middle Ages.

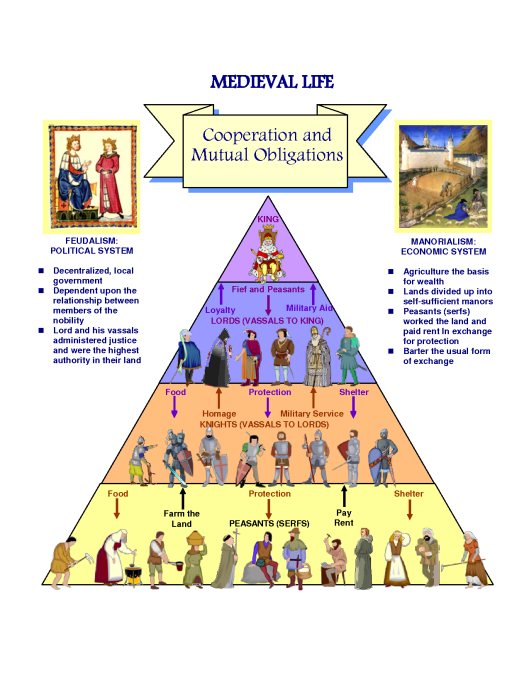

In our world, particularly in western Europe , this is the period which appears physically similar to the end of the Third Age (minus Elves, etc), and, in this period, we find a social/economic structure called feudalism. There has been a great deal of scholarly discussion as to where the base word, feud comes from, but the structure is pretty basic and goes like this (with apologies to all actual medievalists for the gross simplification):

At base, it’s all about two things: land and soldiers.

At the top—the very top—is God, who owns everything. He chooses a king (this comes down to us under the heading of “the divine right of kings” and is similar to “the mandate of heaven” in Chinese history). The king then claims that, because of his position as the Chosen One, he owns all of the land in the country. This land, however, he divides, keeping some for himself, but giving large portions to his chief nobles (the Church also owns a large chunk, but, as religion is rather subterranean in Middle Earth, we’ll leave it at that). They, in turn, divide it among lesser nobles (family members and/or those loyal to them), who, in turn, divide it among the lowest level of nobility (often knights). The simplest parcel is a manor and a knight may hold just one or more than one and this is true all the way up the chain.

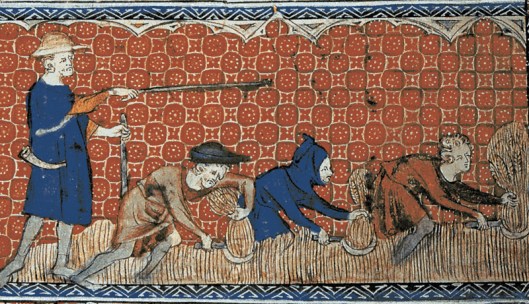

Each manor, in turn, has various grades of inhabitants, from freeholders, who own land but pay taxes on it, to peasants who are free, but are landless and have to work for others, and serfs, who are nothing more than slaves and considered part of the property. Even freemen might still owe an obligation in the form of labor to the lord of the manor.

In return for a manor or for many manors, the nobles at every level owed the king military service.

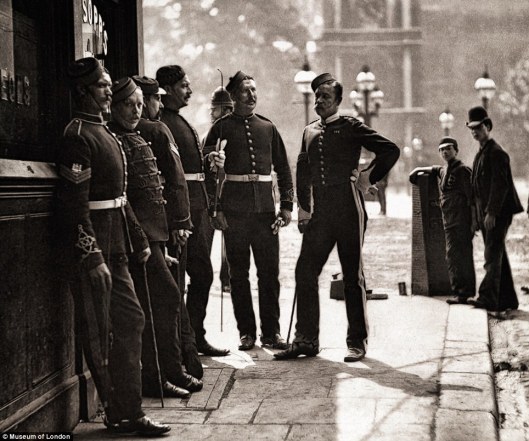

This was necessary, since, with the exception of a certain number of household troops or bodyguards, kings couldn’t afford to keep standing armies on their own.

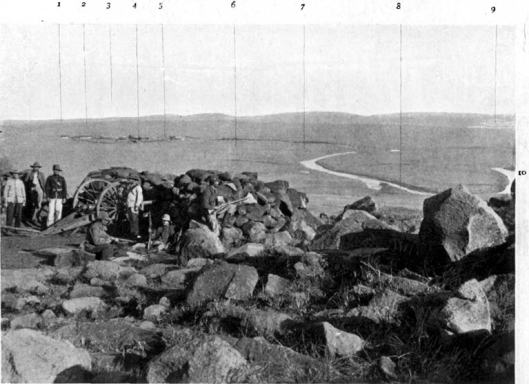

When we began wondering if we could find traces of feudalism in Middle Earth, we thought first about titles. As we said, there are kings, so could we add to them “sirs”, “knights”, “lords”, and such? The densest patch of those would seem to be in The Return of the King, Chapter 1, “Minas Tirith”. Almost at the end of the chapter, Pippin and Beregond’s son, Bergil, watch reinforcements march into the city. Here we can list leaders, almost every one seeming to be a major landowner, judging by the number of his military followers, and all but one called “lord” : Forlong, Dervorin (“son of their lord”), Golasgil, and last and most feudal-like, Imrahil, Prince of Dol Amroth, who comes with “a company of knights in full harness”.

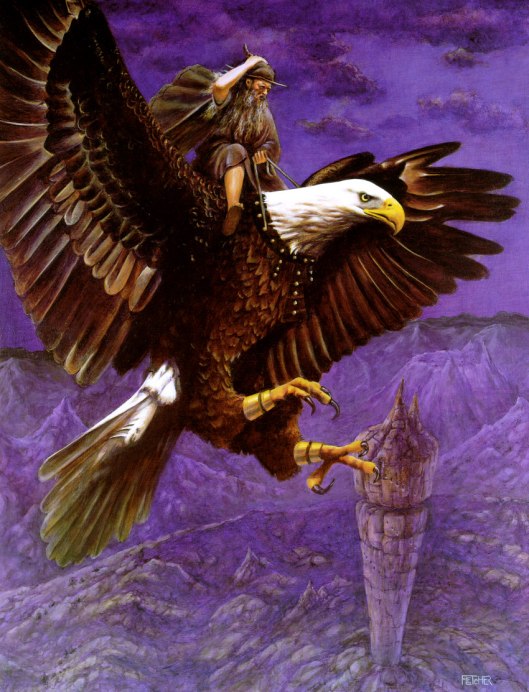

This last reminded us of an earlier posting, when we wondered whether JRRT had ever seen the Prince Valiant comic strip, which occasionally had scenes like this:

Our other thought was this sounded rather like a combination of men entering the Alamo and a gathering of the clans.

To gain a portion of land, all levels of nobles swore oaths of loyalty (called fealty, from Latin fidelitas, through Old French, the legal language of England after the Norman conquest) to those who gave them that land and that oath was commonly done publically and was legally binding.

There were different ways of confirming the earnestness of the person swearing. An altar or saint’s reliquary might be used, as seems to be the case from this scene on the “Bayeaux Tapestry”, in which Harold swears a sacramentum (a “sacred oath”, so Norman propaganda would afterwards claim) to be the vassal (sworn man) of Duke William of Normandy.

Oaths might take the form of the receiver placing his hands between those of the giver and swearing.

An extremely useful site (www.dragonbear.com) provides a number of examples of the oath, which, while varying greatly through time and place, can be encapsulated in this version, from “The Laws of Alfred, Guthrum, and Edward the Elder”:

“Thus shall a man swear fealty oaths.

By the Lord, before whom this relic is holy, I will be to ____ faithful and true, and love all that he loves, and shun all that he shuns, according to God’s law, and according to the world’s principles, and never, by will nor by force, by word nor by work, do ought of what is loathful to him; on condition that he keep me as I am willing to deserve, and all that fulfil that our agreement was, when I to him submitted and chose his will.”

Compare this with Pippin’s oath to Denethor, after Pippin offers his sword to him:

“Here do I swear fealty and service to Gondor, and to the Lord and Steward of the realm, to speak and to be silent, to do and to let be, to come and to go, in need or plenty, in peace or war, in living or dying, from this hour henceforth, until my lord release me, or death take me, or the world end. So say I, Peregrin son of Paladin of the Shire of the Halflings.” (The Return of the King, Chapter 1, “Minas Tirith”)

There is no transfer of land involved here, but certainly there is military service.

JRRT, for all of the amazing detail which he put into Middle Earth, was content, it would seem, to leave it at that: there are kings to whom oaths are sworn, and that idea comes from feudal oaths. There are knights and lords—who else would be in charge of this quasi-medieval world (except, of course, among the non-men—elves, dwarves, and hobbits)? At the same time, this is a huge and wonderfully entertaining adventure, not a disguised treatise on the economic and social substructure of a mirror of the western Middle Ages, as interesting as, if anyone, Tolkien, could have made even that. It is fun, however, to spend a moment imagining what, given another ten years and several more drafts, Middle Earth might have looked like… As always, we ask: what do you think?

Thanks, as always, for reading.

MTCIDC

CD

of which there are seemingly many surviving in several media. Older yet are the Greek masks, the images of which survive in many fewer images, mostly on pots.

of which there are seemingly many surviving in several media. Older yet are the Greek masks, the images of which survive in many fewer images, mostly on pots.

Why are they so scary? Well, for one thing, the clothing is bright and festive, but the face is dead-white and corpse-like, therefore giving a mixed signal of merriment and death at the same time. Perhaps these contradictions should have made the stepmother less trusting (it certainly made

Why are they so scary? Well, for one thing, the clothing is bright and festive, but the face is dead-white and corpse-like, therefore giving a mixed signal of merriment and death at the same time. Perhaps these contradictions should have made the stepmother less trusting (it certainly made

S

S