Tags

Balin, Barrows, Bree, Bridge of Khazad-Dum, Chamber of Mazarbul, Crickhollow, doors, Dwarves, Elven-way, Farmer Maggot, Gandalf, Greenway, Hobbit door, Hollin, Lothlorien, Moria, Nazgul, picaresque, Rivendell, Robert Burns, Tam O'Shanter, The Fellowship of the Ring, The Ford of Bruinen, The Hobbit, The Legend of Sleepy Hollow, The Lord of the Rings, The Prancing Pony, Tolkien, Washington Irving, Watcher in the Water, Weathertop, West-door, West-gate

Welcome, dear reader, as always. It’s a rather gloomy late autumn day here as we write this, fitting, perhaps, for the gloomier The Lord of the Rings after the cheerier (well, sometimes) The Hobbit, as we continue our look at the functions of doors and their equivalents in JRRT.

If you’ve read our previous posting, you’ll know that, in it, we examined doors and gates in The Hobbit, dividing them into two basic categories: doors which might lead to safety and doors which led to danger, all based upon Bilbo’s remark about how dangerous it can be, just stepping outside your door.

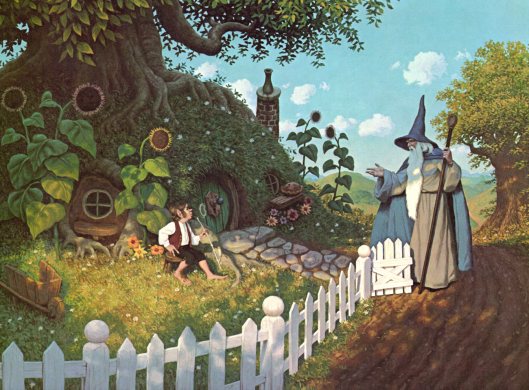

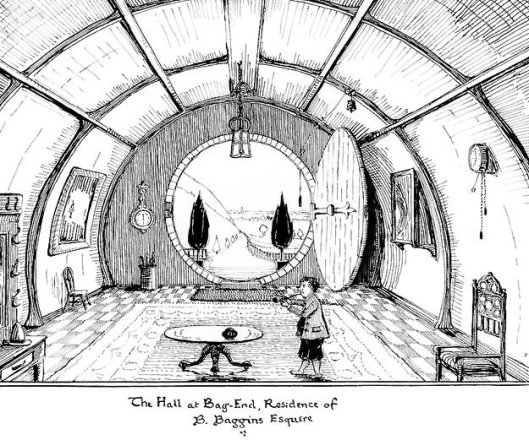

Bilbo’s door adventures had begun with his own.

When comparing the two books, we get a strong sense of the episodic nature of The Hobbit: we can almost break it down into movement between doors, from the arrival of the dwarves to the knock of Gandalf and Balin, giving it more the feel of a picaresque novel: that is, a novel with an goal, but with much of its focus upon the adventures along the way, adventures which don’t always necessarily lead to that goal. This gives it a lighter tone, as well—after all, it was meant as a children’s book in a time (1937) when such books were understood in general never to be too solemn. The Lord of the Rings, in contrast, develops an almost grimly-focused forward motion, which impels it even when the Fellowship breaks into two after the death of Boromir, and much of the action spreads from Frodo and Sam on the way to Mordor to the separate adventures of Merry and Pippin in Rohan and Gondor.

So what might we see as the first door—in either sense—in The Lord of the Rings? we asked ourselves. And we supposed that we might see minor doors of safety at Farmer Maggot’s and Frodo’s new home in Crickhollow, in both cases brief refuges from the Nazgul, but, as we said in our last posting, doors commonly have some sort of challenge to them—and challenger—and the first one of those appears briefly at the hedge in Bree:

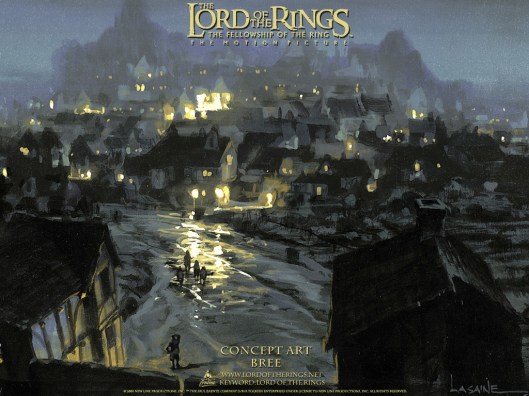

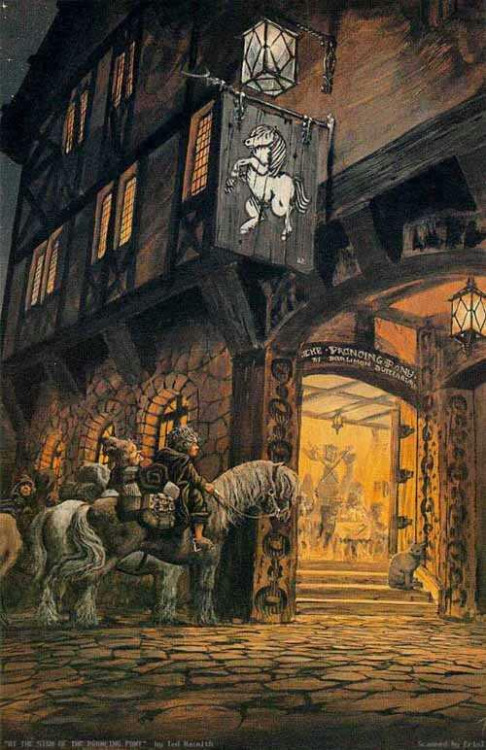

“They came to the West-gate and found it shut; but at the door of the lodge beyond it, there was a man sitting. He jumped up and fetched a lantern and looked over the gate at them in surprise.” (The Fellowship of the Ring, Book 1, Chapter 9, “At the Sign of the Prancing Pony”)

The watchman, when his challenges (and maybe a little too-inquisitive challenges) are turned aside, lets them in and they reach The Prancing Pony, only to escape murder in their beds and the loss of their ponies.

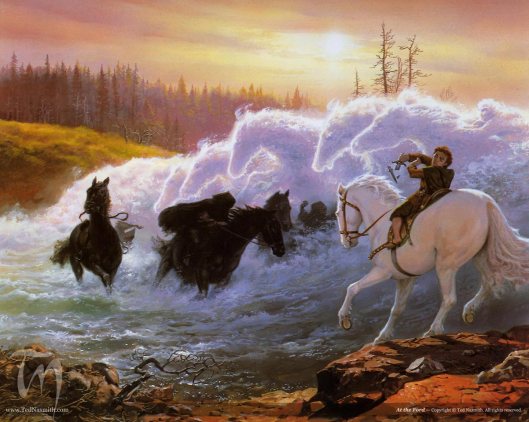

The first gateway which leads to real safety, however, isn’t a door or gate at all, but a natural barrier (with some magical help): the Ford of Bruinen. Here, the role of traveler and challenger is reversed, as the challenged are the Wraiths and the challenger is Frodo, but it is the power of the Elves which closes the door.

(It is interesting here that Tolkien has chosen not to take advantage of the folk belief—if you know “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow” by Washington Irving, or its inspiration, the poet Robert Burn’s “Tam O’Shanter”, this will be readily familiar to you—that evil spirits are unable to cross running water, even at a bridge.

To reach the Shire, the Wraiths have had to cross several bodies of water and now their hesitation to traverse another appears to be derived from their confidence that they can now control Frodo—either by the influence of the Ring, or perhaps from his wound—and call him back across the stream to them.)

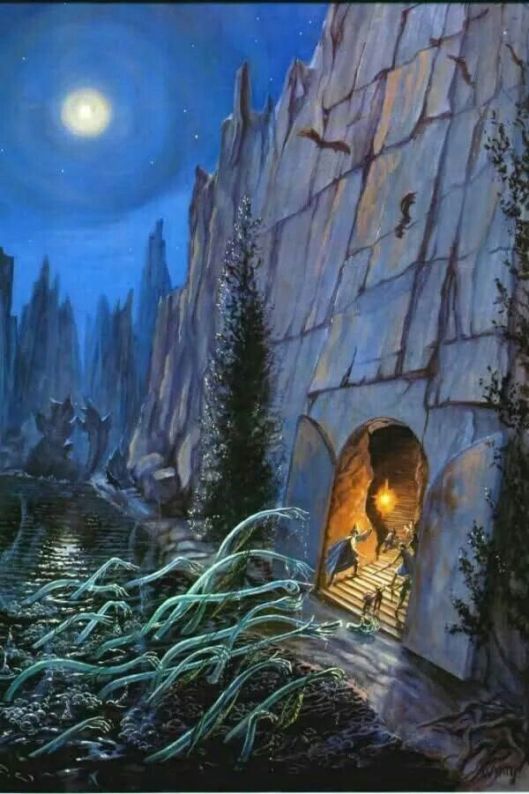

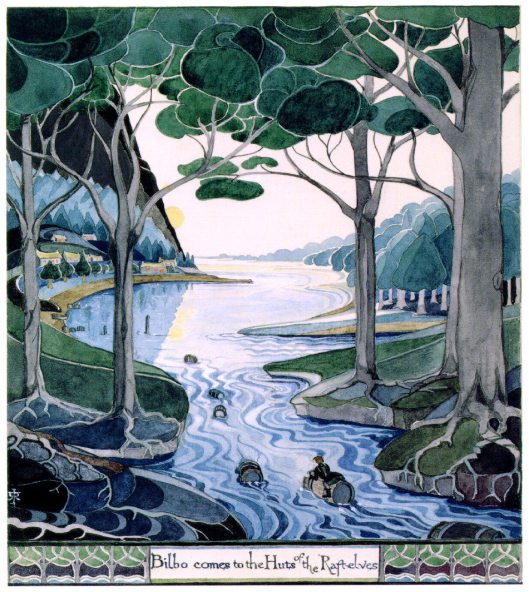

From Rivendell, the next such door is that at the western side of Moria.

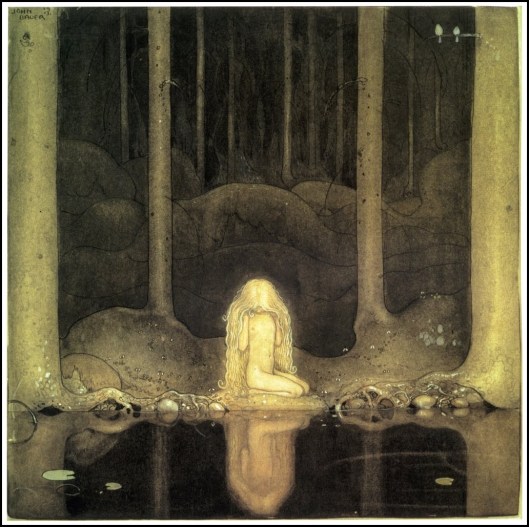

Here, there is no living challenger. Rather, it is a kind of riddle—or, at least, it is initially understood as such—which bars the way. Its answer is simple, which led us to wonder, what is the purpose of this door scene in the story? As the creature in the pool

barricades the door behind them, it adds to the tension: the Fellowship has been watched and, from the hostile mountains to the wolves to the tentacle thing, it has been forced into darker and narrower ways, those ways seemingly chosen by the malevolent force observing their journey. As well, it suggests the gradual decay of what was once a vibrant, active culture, as Gandalf explains:

“Here the Elven-way from Hollin ended. Holly was the token of the people of that land, and they planted it here to mark the end of their domain; for the West-door was made chiefly for their use in their traffic with the Lords of Moria. Those were happier days, when there was still close friendship at times between folk of different race, even between Dwarves and Elves.” (The Fellowship of the Ring, Book 2, Chapter 4, “A Journey in the Dark”)

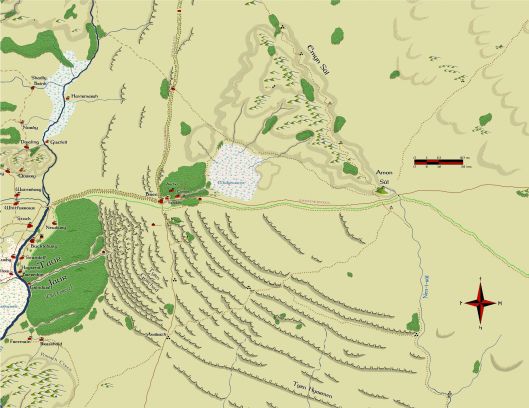

This is a theme throughout The Lord of the Rings and one which, we believe, adds to its power: the events of the close of the Third Age are set against a background of other times and other events and the landscape still bears traces of those times, from the Barrows to the Greenway and Weathertop and far beyond. As well, so many of those traces suggest that violence and the dark spirit of Sauron, sometimes through his agents, sometimes in person, have had much to do with their end.

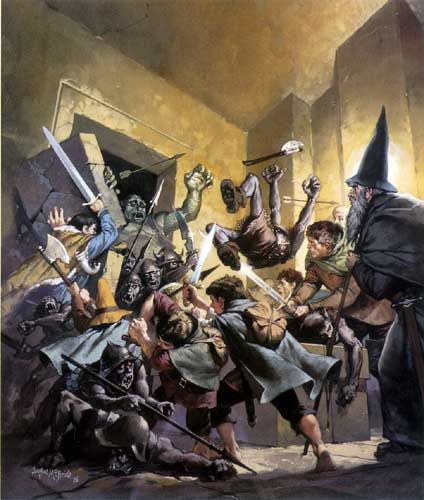

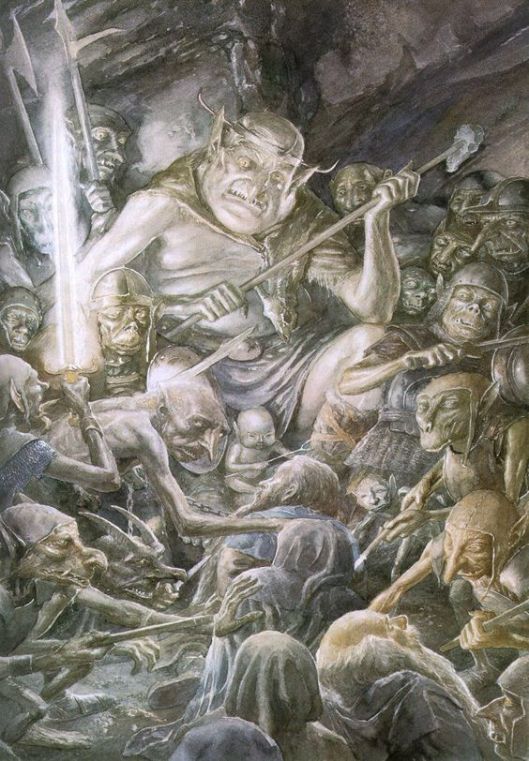

Now that the Fellowship is within Moria, it encounters its next door: that of the Chamber of Mazarbul.

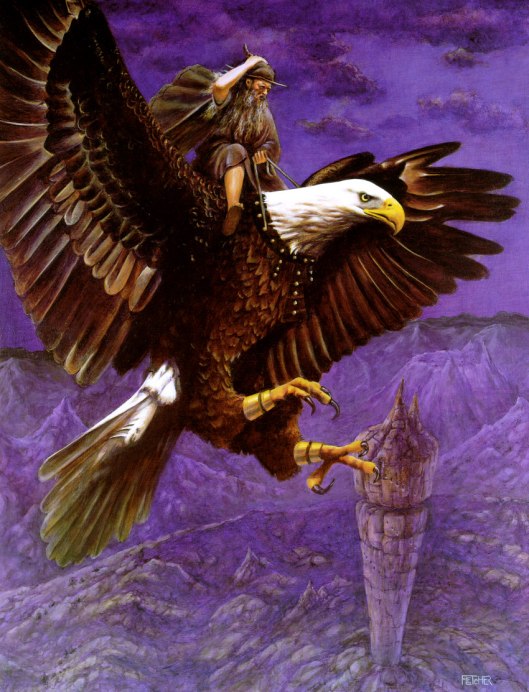

Here, they are the challengers, when forced to defend themselves from a horde of “Orcs, very many of them…And some are large and evil: black Uruks of Mordor.” (The Fellowship of the Ring, Book 2, Chapter 5, “The Bridge of Khazad-Dum”). There is a second door, however, and, when they have beaten back their attackers, they escape by it—but only so that Gandalf may be the challenger at a crossing—as Frodo was at the ford—at the Bridge of Khazad-Dum, although here magic apparently cannot save him, as it had Frodo.

With Gandalf gone, we see the repetition of a scene from The Hobbit—the escape through a crowd to the outside world:

“…and suddenly before them the Great Gates opened, an arch of blazing light.

There was a guard of orcs crouching in the shadows behind the great door-posts towering on either side, but the gates were shattered and cast down. Aragorn smote to the ground the captain that stood in his path, and the rest fled in terror at his wrath.” (The Fellowship of the Ring, Book 2, Chapter 5, “The Bridge of Khazad-Dum”)

At this moment in The Hobbit, Bilbo had used his newly-discovered ring to escape (albeit with the loss of a few buttons), but Aragorn’s sword clearly does just as well.

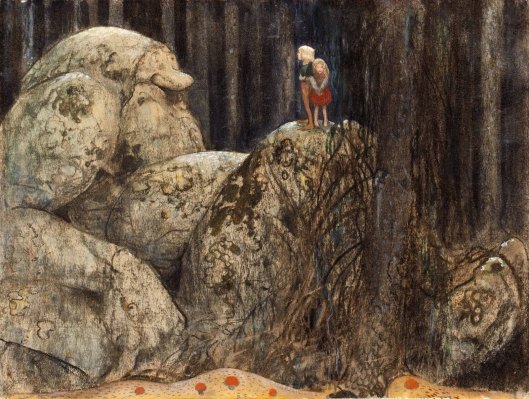

It is easy to see just how prevalent the pattern is: even after that harrowing moment of being chased through the mines and losing Gandalf, where there is a door, there is someone at it to make a challenge, and this holds true even without an actual door, as the remaining members of the Fellowship seek to enter Lothlorien and are stopped by Elven sentries in a tree. (The Fellowship of the Ring, Book 2, Chapter 6, “Lothlorien”)

And the pattern continues, even as the Fellowship breaks up, but let’s take a moment to see what we’ve found so far. On the side of doors to safety, we have: Bree (although it’s not so safe as it looks), the Ford of Bruinen, the main door of Moria, and the entrance to Lorien. As for doors to danger, there are: the western doors of Moria and the door to the Chamber of Mazarbul.

In the third installment, we shall see just how many more doors/gates/entryways we find which continue to fit the pattern—and there are a fair number of them.

Thanks, as ever, for reading.

MTCIDC

CD

Originally, this had been the site of a Gondorian strongpoint, but, as Gondor waned, it fell into disuse until taken over by Saruman with the permission of the Steward of Gondor, Beren. When

Originally, this had been the site of a Gondorian strongpoint, but, as Gondor waned, it fell into disuse until taken over by Saruman with the permission of the Steward of Gondor, Beren. When

Like Saruman, Macbeth is overcome, gives in, murders Duncan, seizes power, but, also like Saruman, can not retain it and, interestingly, an element in his defeat closely resembles an element in Saruman’s defeat: trees.

Like Saruman, Macbeth is overcome, gives in, murders Duncan, seizes power, but, also like Saruman, can not retain it and, interestingly, an element in his defeat closely resembles an element in Saruman’s defeat: trees.