Tags

An Unexpected Party, Bad End, Baggins, ceramics, clay bank, coal, coins, cork, crafts, cutlery, Dwarves, Esther Forbes, Gondorian money, Hobbits, Isengard, Johnny Tremain, lead, Lloyd Alexander, Longbottom Leaf, Mayor, Michel Delving, mines, Postal Service, pottery, realien, Renaissance, Robert II of Scotland, Saruman, Shirriffs, silica, Silver, Taran Wanderer, Thain, The Green Dragon, The Hobbit, The Lord of the Rings, The Shire, Tolkien

Welcome, dear readers, as always.

In our last post, we began a series responding to the question: what makes the Shire the Shire?

We began with the government, which turned out to be very rudimentary: a Thain (hereditary), a Mayor (elected), a postal service (not known how chosen), Shirriffs (a kind of border patrol—volunteer). Since the Thain and Mayor were principally honorary positions, there was perhaps no salary attached. As for the postal service (called “Messengers”) and the Shirriffs, we presume that there must have been some sort of payment, although we are not told so. Since, in our world, we pay for the police and the post office through taxes, we wondered how the same services in the Shire were paid. This led us to the question of the Shire economy in general.

In a letter of 25 September, 1954, JRRT wrote to Naomi Mitchison:

“I am more conscious of my sketchiness in the archaeology and realien [“physical facts/things of real life”] than in the economics: clothes, agricultural implements, metal-working, pottery, architecture and the like…I am not incapable of or unaware of economic thought; and I think as far as the ‘mortals’ go, Men, Hobbits, and Dwarfs, that the situations are so devised that economic likelihood is there and could be worked out…” (Letters, 196)

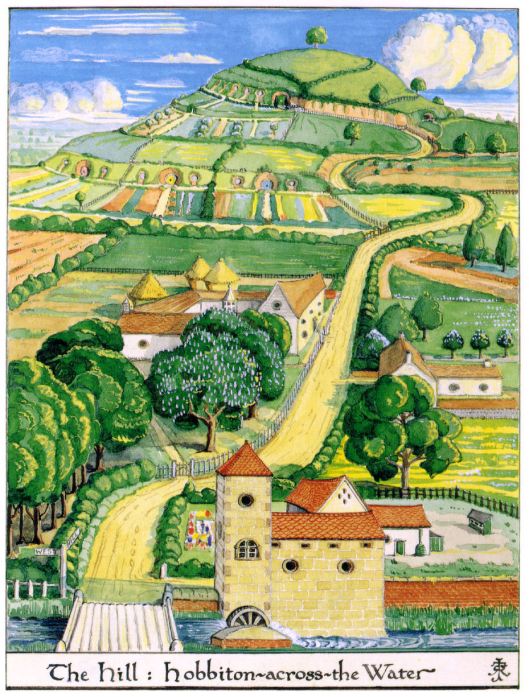

The Shire would appear to be an agriculturally-based economy:

“The Shire is placed in a water and mountain situation and a distance from the sea and a latitude that would give it a natural fertility, quite apart from the stated fact that it was a well-tended region when they [hobbits] took it over.” (Letters, 196)

He adds to this that, when the hobbits took control of the Shire, that included “a good deal of older arts and crafts”, suggesting that the solution to the problem of the production of “clothes, agricultural implements, metal-working, pottery”—all the Realien, as he calls them, is assumed. How and from whom such things were taken over is not explained and such production, in any community, is not a small matter: “things of real life” are many and complicated.

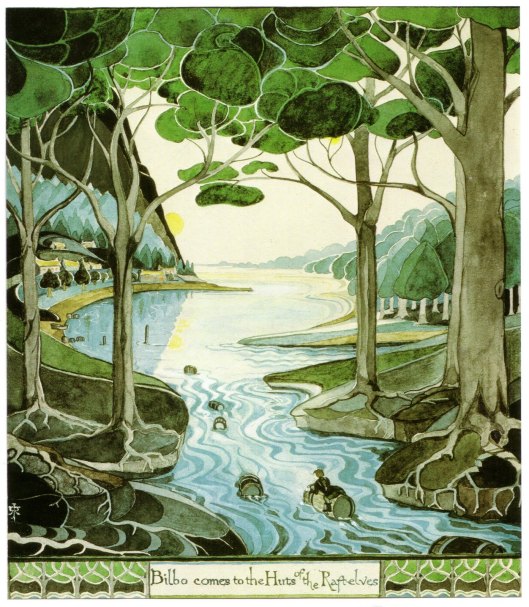

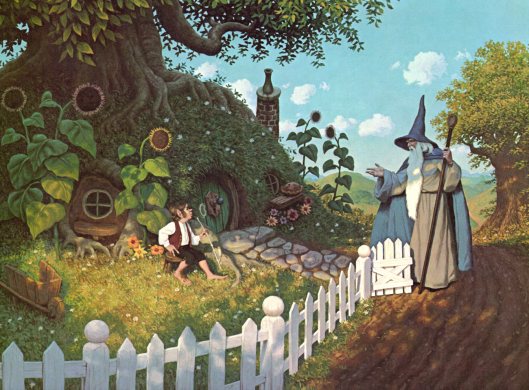

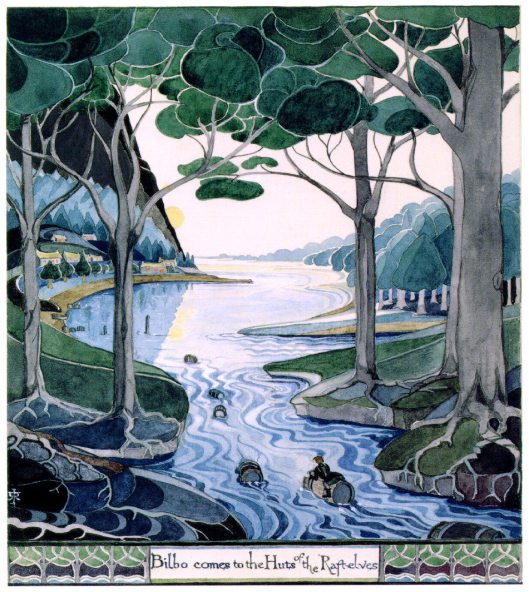

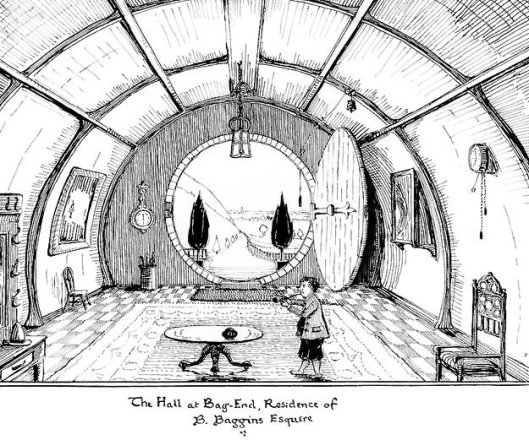

Consider, for example, just one moment at Bag End. The Baggins appear to have been well-to-do, even without the treasure Bilbo brought back from his trip. His house is extremely well-furnished and the Baggins certainly don’t want for provisions, as we know from descriptions both in The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings, as well as Realien, as the Dwarves’ clean-up song reminds us:

Chip the glasses and crack the plates!

Blunt the knives and bend the forks!

That’s what Bilbo Baggins hates—

Smash the bottles and burn the corks!

(The Hobbit, Chapter 1, “An Unexpected Party”)

If we take this line by line, we come up with the following: glasses, plates, knives, forks, bottles, corks.

Glasses and bottles (as well as the window panes at Bag End) require a glassblower and perhaps a glazier.

Plates require a potter.

Knives and forks were once made by cutlers (and forks are very advanced for a Middle-earth which is mostly medieval—although classical people used them in food preparation, it was only during the Renaissance that they began to appear as an eating utensil—western Medieval people ate with knives, spoons, and fingers).

(And next is a Renaissance fork, found in the foundations of the Rose Theatre)

Corks come from vintners and brewers (in our world, vintners only began using cork as a sealant in the 17th century, we have read).

Take those objects a step farther back and you find:

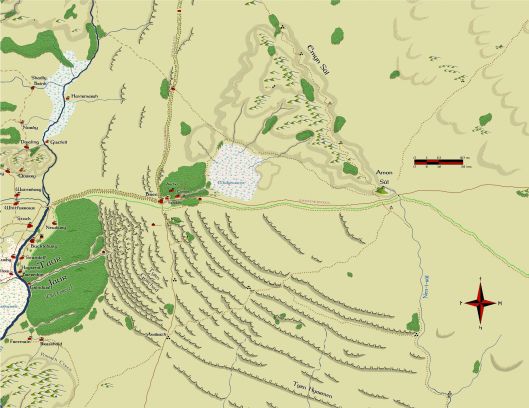

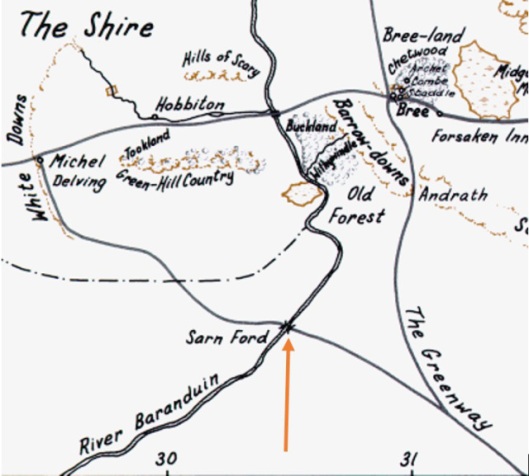

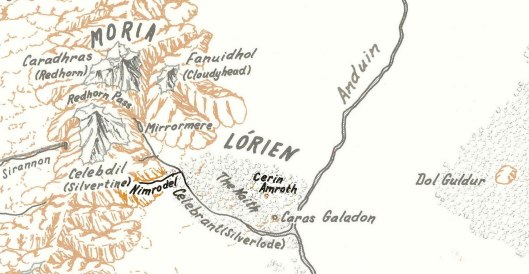

- glasswear, bottles, and window panes require silica and something to make it more stable, like lime (from limestone) or lead, which leads us to the question of where the ingredients come from. Silica is sand and can be found in many places—perhaps it might come from the west coast of Middle-earth? If all of the Shire is like the White Downs, where Michel Delving is located, it may be situated upon a vast deposit of chalk (more about Shire geography in our next posting). Lime would then have to be imported. As we have no record of mines in the Shire, the same would be true for lead.

- ceramics, like plates, are made of clay and all sorts of clay are used to make pottery, but all need to be dug out, usually from beds found near streams, rivers, or places like canyons or ravines. The Shire seems fairly well-watered, so we presume that the clay used to make Bilbo’s dishes was local.

- knives and forks would be made of iron, early steel, or silver (with silver, plus an alloy to make them stronger)—here, again, we would need mines, for the iron ore and silver

- cork in our world is actually tree bark from the cork trees which grow in hot, dry southwest Europe (Spain/Portugal) and northwest Africa

1, 2, 4 (and possibly 3) require raw materials of which no mention is made in the Shire and 1, 2, and 3 all need especially hot fires to make them, possibly using charcoal (made locally?) or coal (again, no mines discussed). And this is just, basically, four items.

So many import possibilities: what about export? We have solid evidence for one, which Merry and Pippin have discovered at Isengard:

“My dear Gimli, it is Longbottom Leaf! There were the Hornblower brandmarks on the barrels, as plain as plain. How it came here, I can’t imagine. For Saruman’s private use, I fancy. I never knew that it went so far abroad.” (The Two Towers, Book 3, Chapter 9, “Flotsam and Jetsam”)

It should always be remembered that these are works of fantasy, of course, and, unless there is some novelistic purpose which employs a potter as a character (in Taran Wanderer,

by Lloyd Alexander, book 4 of The Chronicles of Prydain, for example, the hero, Taran, spends a little time as an apprentice potter, among other trades) or the making of silverware (something one might read about in Esther Forbes’ Johnny Tremain,

where Johnny is an apprentice to a silversmith), it would seem completely unnecessary to spend narrative time discussing raw materials, imports, exports, or the manufacture of day-to-day items. We have taken the time, however, because, where, sometimes, we write about the parallels between Middle-earth and something here in our world, here the complexity of ordinary things in our world is completely forgotten in Middle-earth, or simply taken for granted, as JRRT implies in the letter cited above. If we are to examine Shire economics, however, we must, at least, consider them. As well, although we may keep saying, “No evidence for”, we think that, even if there is no potter or tin mine in the text, prompting readers to remember that, in the real world, there would have been one is a useful exercise and, for us, at least, makes the story that much more real.

But now we come to the subject of paying for Realien, or for anything else in the Shire, be it for the Shirriffs or for a pint at The Green Dragon.

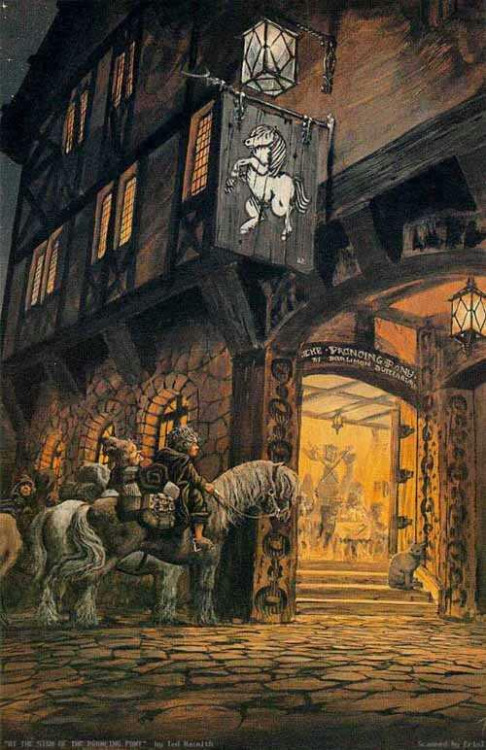

In a totally rural economy many things might be obtained through barter: in return, for payment, please take 10 chickens, or a sack of grain. (And perhaps we see something like this in “The Scouring of the Shire”, when Hob Hayward tells Merry that, “We grows a lot of food, but we don’t rightly know what becomes of it. It’s all these ‘gatherers’ and ‘sharers’, I reckon, going round counting and measuring and taking off to storage.”—this looks like taxes, “paid in kind”). Such might work for, say, trading a hen for a bowl, but would certainly not do for that pint—or for the bill at The Prancing Pony. Coins and their values are not mentioned in Tolkien, but their effect is felt, all the same: when Frodo buys a house in Crickhollow, we doubt he does it with cows!

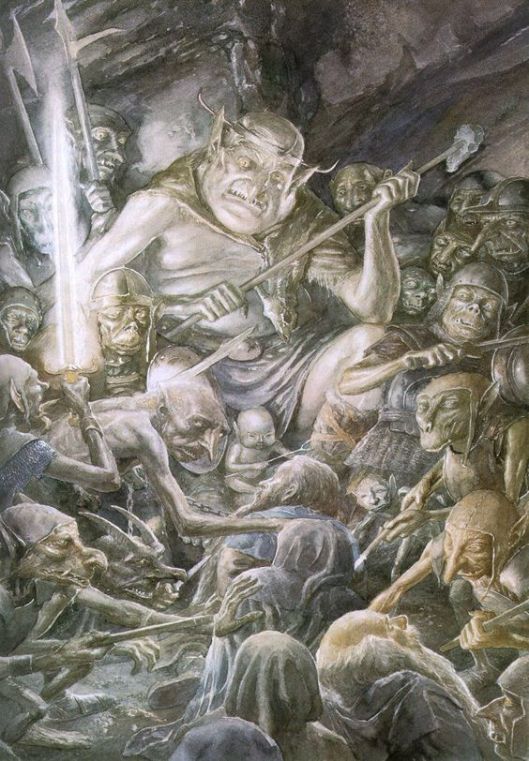

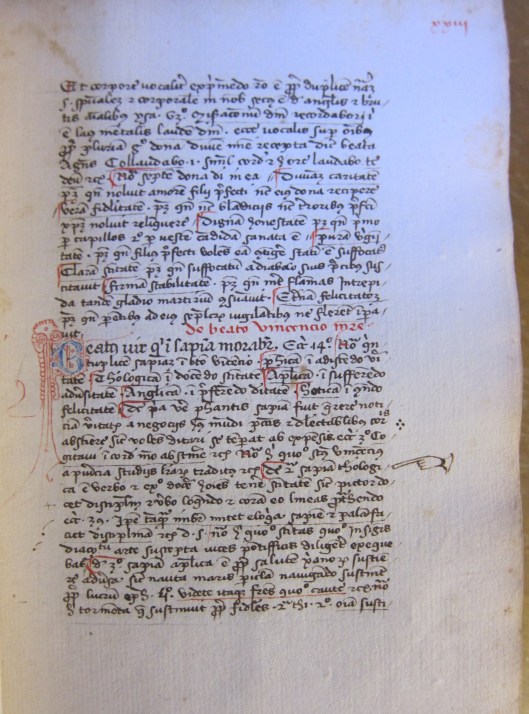

(We discussed Middle-earth money in an earlier posting and it seems to us that it would be fun to create, say, Gondorian money—here’s one possibility

It’s actually a coin of Robert II of Scotland—1316-1390—but, changing the crown, could you imagine this as something issued earlier in the Third Age, say?)

This has been perhaps a rather long-winded and prosy posting (perhaps not for nothing did Thomas Carlyle, in 1849, call economics “the dismal science”?), for which we ask our readers’ pardon, but, if it helps to flesh out our portrait of the Shire, it was worth it, we feel. Our next, we hope will be a bit lighter, being on the physical “look” of the Shire, from its geography to its geology to its architecture.

Thanks, as ever, for reading.

MTCIDC

CD

)

)