Tags

Arawn, Arthur Rackham, Badb, Branwen, Celtic Association of North America, Christopher Williams, Dallben, Disney, Fflewddur Fflam, Gundestrup Cauldron, Hercules, King Arthur, Lady Charlotte Guest, Lloyd Alexander, Lord of Annwn, Mabinogi, Mabinogion, Macbeth, Moirai, Morrigan, Norns, Princess Eilonwy, Pwyll, Shakespeare, Taran Wanderer, The Black Cauldron, The Castle of Llyr, The Chronicles of Prydain, the Fates, The First Two Lives of Lukas-Kasha, The High King, The Iron Ring, The Marvelous Misadventures od Sebastian, The Wizard in the Tree, The Xanadu Adventure, Time Cat, Walking Dead, Westmark, World War Z, zombies

Welcome, dear readers, as always.

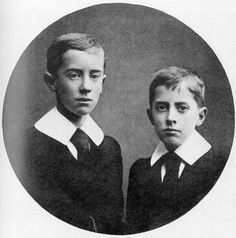

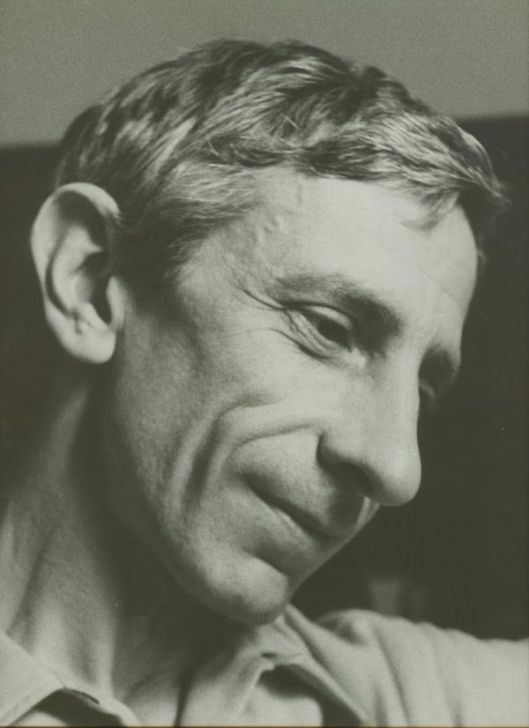

In our last posting, we said that we intended to talk about otherworlds and also about one of our favorite YA (“Young Adult”) authors. That author is Lloyd Alexander (1924-2007)

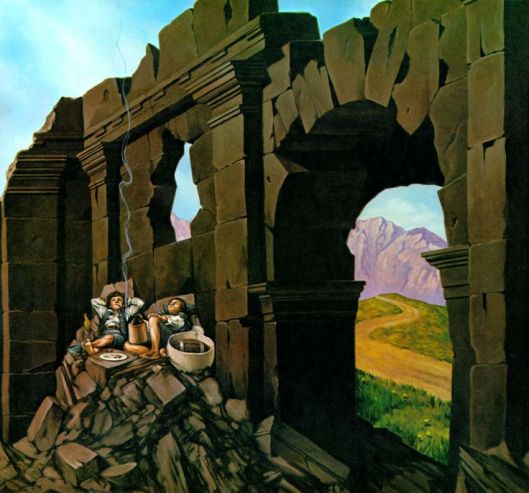

and we thought we’d open our exploration with one aspect of otherworlds: the dead, and with one aspect of them as seen in the second volume of Alexander’s pentalogy, The Chronicles of Prydain (1964-1968),

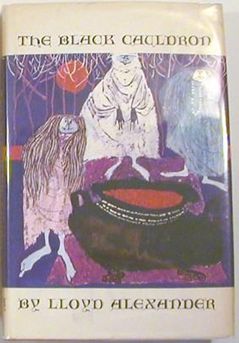

The Black Cauldron.

Alexander wrote more than forty books, mostly YA.

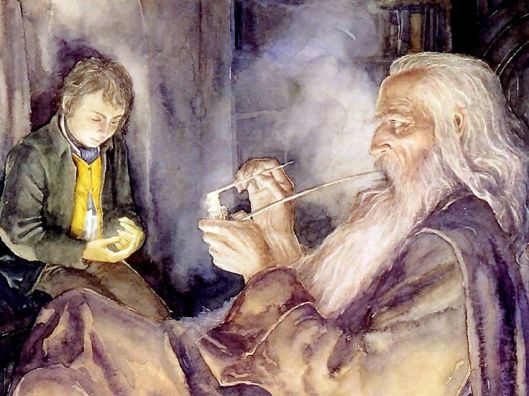

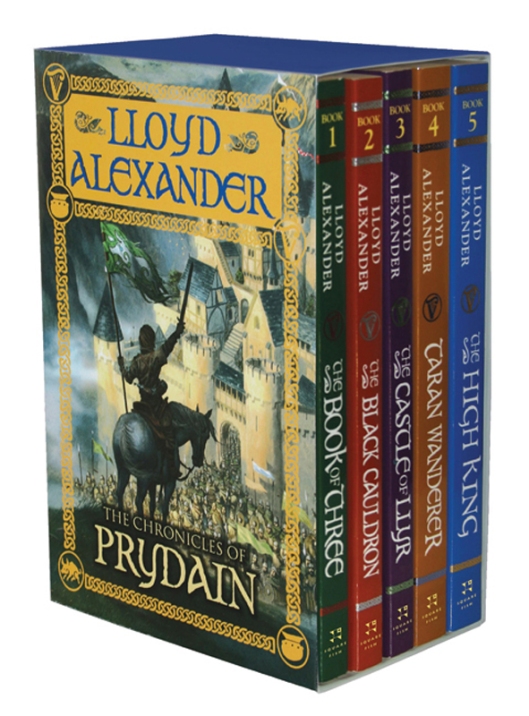

Some are series, like “Westmark” and “Vesper Holly”, and some are one-offs, like The Iron Ring, and we’ve enjoyed them all, but those we have returned to most often are the books which make up The Chronicles: The Book of Three, The Black Cauldron, The Castle of Llyr, Taran Wanderer, The High King. These are lighter books than their Tolkien cousins, but they are equally serious, with genuinely unhappy moments, and a feel which might, at times, seem like a combination of The Hobbit and “The Grey Havens”, which is why we return to them. The characters can be familiar, like Taran the Assistant Pig Keeper, who is a foundling, but much more, and Dallben the very quiet wizard, but also unusual, like the Princess Eilonwy, a chatterbox with a practical mind, or Gurgi, who is somewhere between human and something else, and who talks in a distinctly rhythmic way, or the would-be minstrel, Fflewddur Fflam, who has trouble with the truth—something which his harp points out on a regular basis.

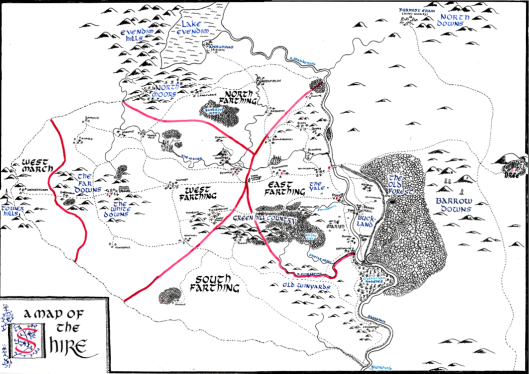

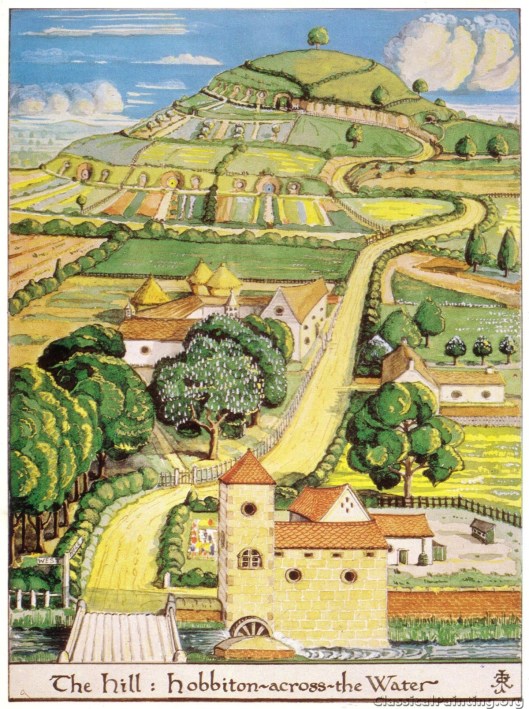

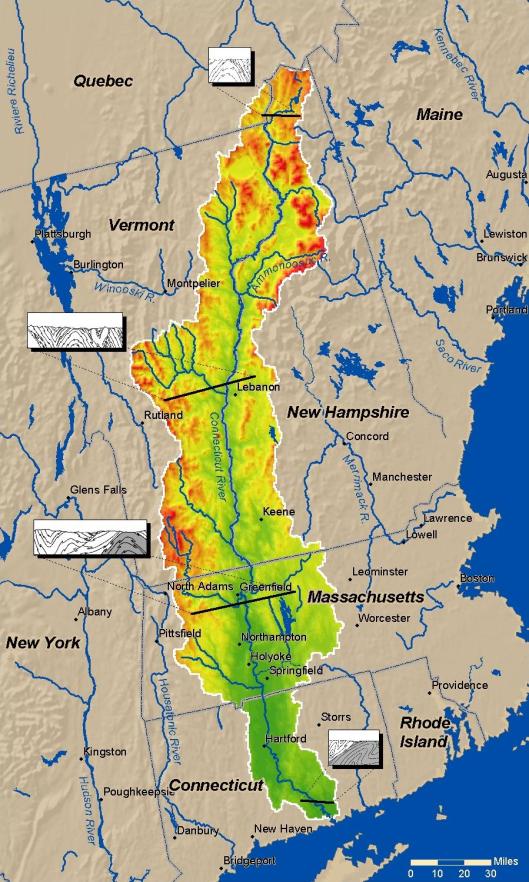

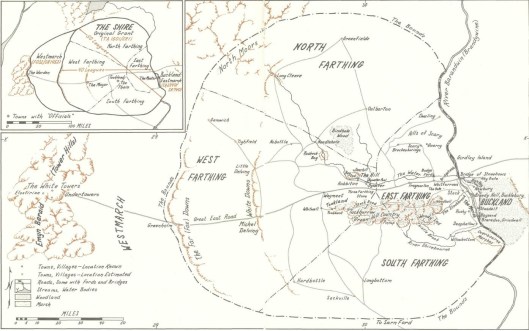

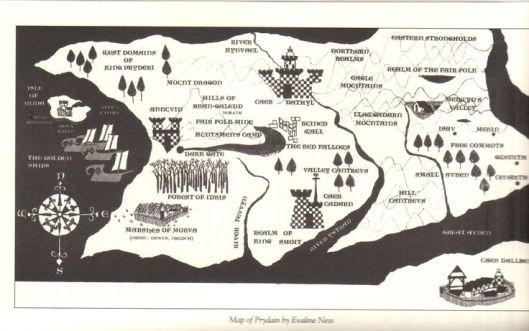

All of these characters and more have their home in “Prydain”,

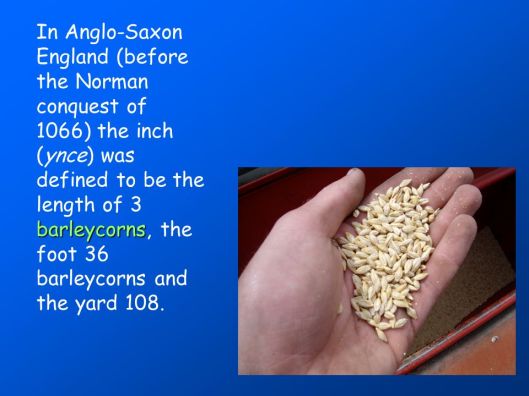

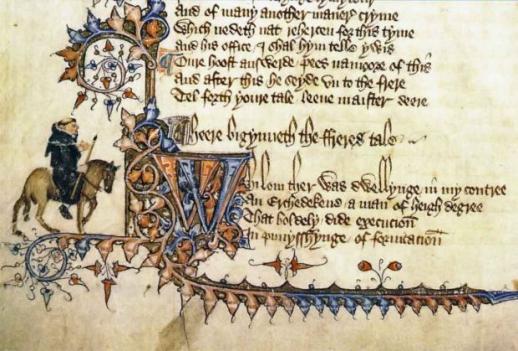

which is a kind of imaginary Wales, just as names and story elements in the pentalogy are derived from Welsh mythology and, in particular, from the medieval collection now called The Mabinogi (or Mabinogion—the title being the subject of much discussion). The first complete English translation was that of Lady Charlotte Guest (1838-1845) and it’s available at Sacred Texts. Here’s the link for the second edition of 1877).

In an interview with Scholastic, Alexander tells us that he spent a little time in Wales during World War II and fell in love with it and that the mythological part of the story came from a childhood love of King Arthur. (Here’s a link to the text of the interview—as well as one to the filmed interview, and, as a bonus, a separate film on Alexander.)

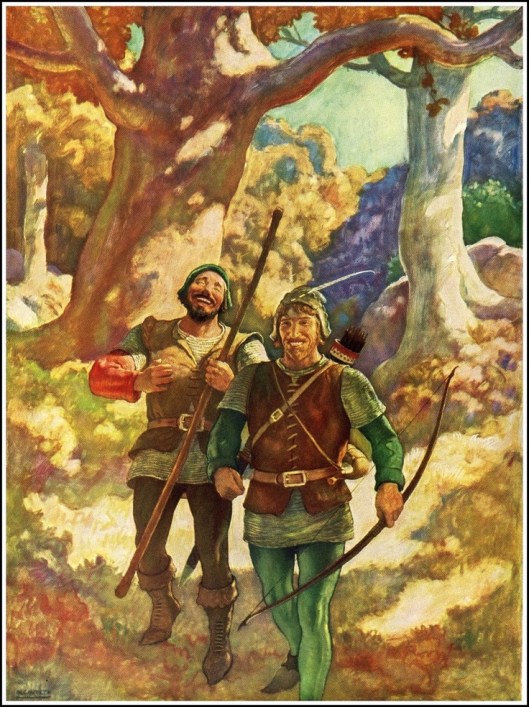

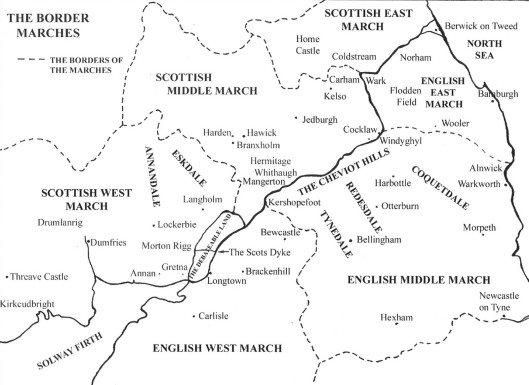

The general thread of the stories is derived, in part, from the story of Pwyll. (Yes—it looks unpronounceable, but it’s really not—go to this link from the Celtic Studies Association of North America to hear—for English speakers, that ll at the end would be the hardest—it’s said out of the corner of your mouth as a kind of musical hiss—if you know Sylvester the Pussycat from the old Warner Brothers cartoons,

you can get a rough idea of the sound when he says—as everybody in the 1930s and 1940s appears to have said nearly constantly, if you believe their movies– “Say!”)

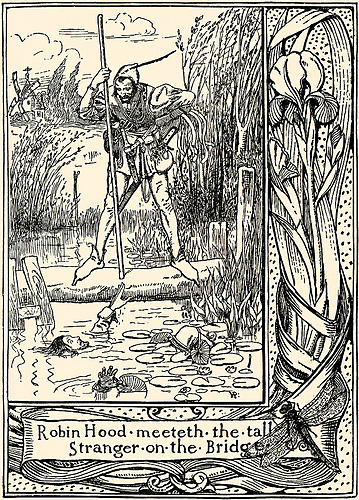

Pwyll is a prince who, when out hunting, has an encounter with Arawn (AH-ruhn, more or less), the Lord of Annwn (AH-nuhn), which is the name for the Otherworld. In the Alexander books, Arawn plans to conquer this world and Taran and his friends are brought into combat with his allies and Arawn himself again and again until Arawn’s final defeat.

One element in Arawn’s plans is a magical cauldron,

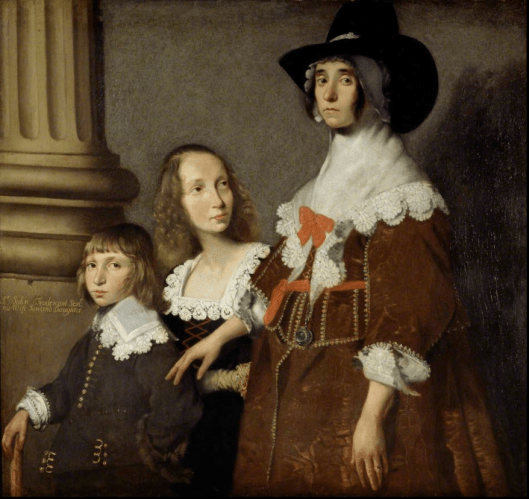

which can bring back the dead. This is an idea which Alexander borrowed from another of the Mabinogi stories, that of Branwen, here depicted in a 1915 painting by Christopher Williams.

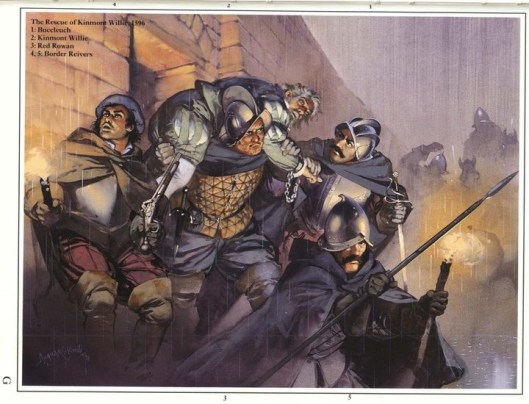

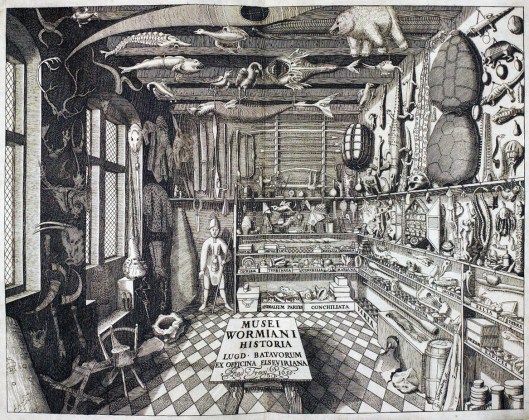

It has been suggested that the use of this cauldron can be seen upon the “Gundestrup Cauldron”, a silver vessel discovered in a peat bog at Gundestrup, Denmark, in 1891.

It’s a mysterious thing with lots of academic argument over who made it, where, and when, with dates between 200bc and 300ad, besides its purpose, but, among its many puzzling scenes is this:

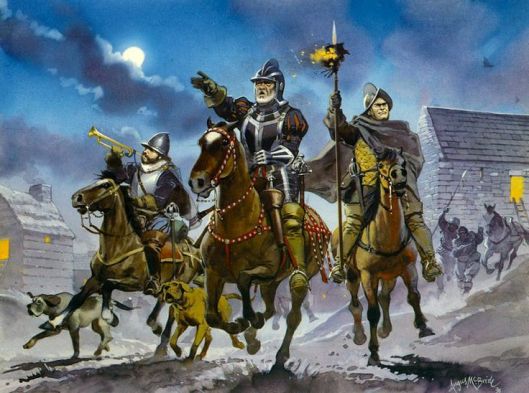

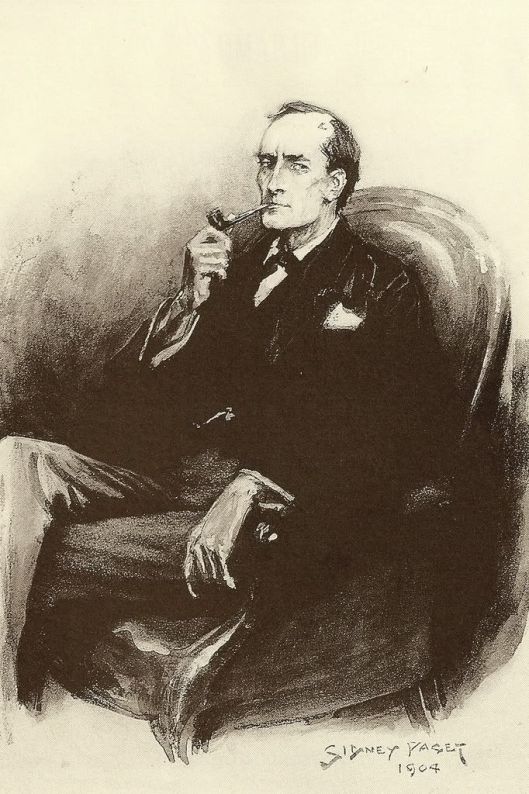

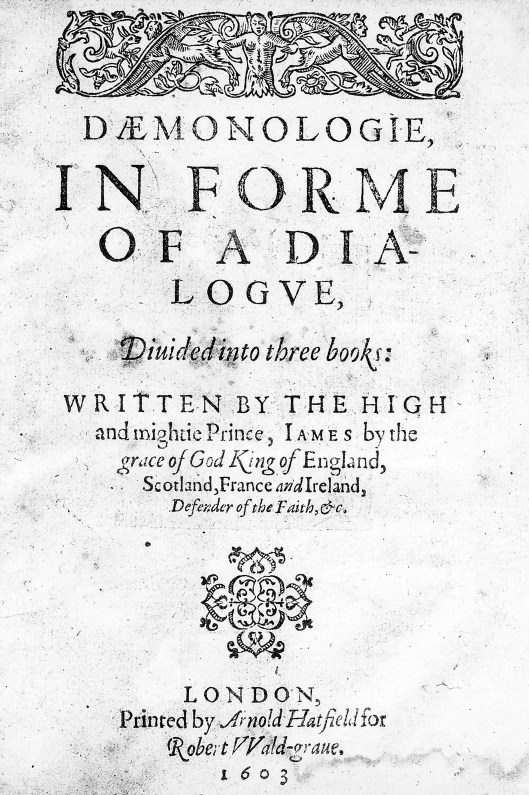

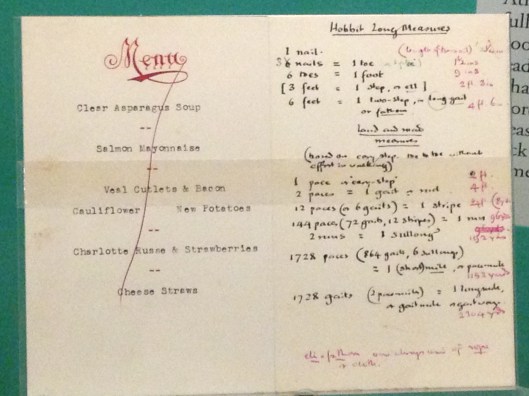

In The Black Cauldron, although Arawn had once controlled it, the vessel really belongs to three mysterious figures—Orddu, Orwen, Orgoch—who live in a hut in the Marshes of Morva. Three haglike figures around a cauldron suggest another such trio—the three weird sisters in Shakespeare’s Macbeth.

We believe, in fact, that these (in the play) are the three incarnations of the Irish goddess, the Badb (“Crow”). This image comes from a weird and interesting site called “Mygodpictures.com”.)

She was also known as the Morrigan (“Great Queen”), who was thought to appear on battlefields, before, during, and after conflict.

These hags also remind us of the three figures of fate from the Norse tradition, the Norns (seen here in an especially ghostly picture by Arthur Rackham)

and, beyond those, the Moirai, the three fates of Greco-Roman religion

as well as the Fates from Disney’s Hercules

to go from the serious to the nearly-silly.

In recent years, popular entertainment has used the re-animated, from World War Z

to The Walking Dead,

and can we ever escape zombies?

For us, however, perhaps the most powerful of images lies not in the gross graphics of decaying flesh, but that, in the story of Branwen, the dead can be brought back, but cannot speak. Why is this? It’s a haunting question: is it that death—or rebirth—is so terrible that they are blocked from talking about it? Is it that no one is alive who cannot communicate, in some form or other? What do you think about the mute dead, dear readers?

Thank you, as always, for reading and definitely

MTCIDC

CD