Tags

19th Century, A Midsummer Night's Dream, Anglo-Saxon, Arthur Rackham, Beren and Luthien, dance, Dicky Doyle, Elbereth Gilthoniel, elf ring, Elves, Fairy, fairy ring, Fairy Tale, Folklore, In Fairyland, Kenneth Grahame, Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens, Song, The Hobbit, The Lord of the Rings, Tolkien, Victorian, William Shakespeare

Dear readers,

Welcome, as always.

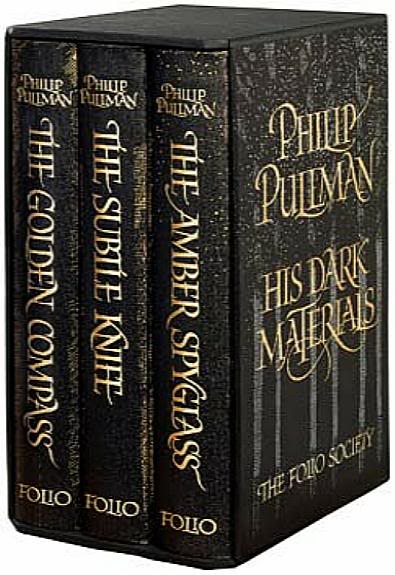

In The Lord of the Rings, Elves are powerful, human-like figures– immortal, skilled, and revered as counselors. In Tolkien’s work, however, they have not always been this way– early drafts suggest a sort of Victorian confusion, as if Tolkien’s elves have ancestral ties to both the tall, beautiful elves of the Anglo-Saxons, and to the jovial, delicate elves and fay of the mid- to late- 19th century.

In the beginning of June this year, Christopher Tolkien published an edited version of his father JRRT’s story, “Beren and Luthien”, which was originally published as a part of The Silmarillion, a history of the Elves.

Within this book are previously unpublished earlier drafts and versions of the story, and in the introduction to them, Christopher Tolkien comments upon them: Beren was originally a gnome (which he was quick to explain meant an immortal figure– not what we would find in gardens),

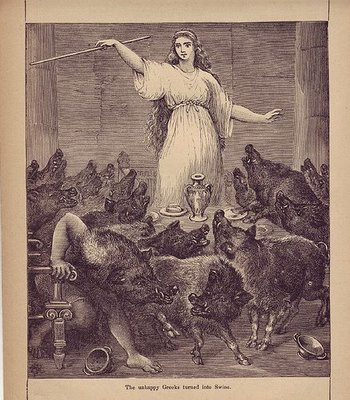

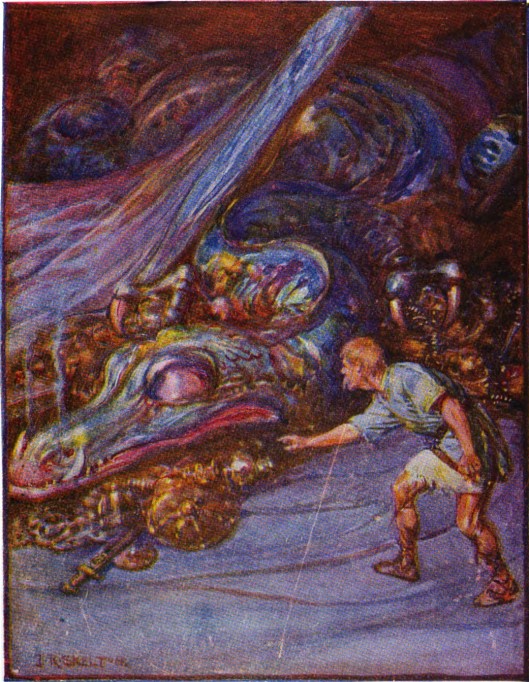

and then an elf, before his final incarnation as a mortal man. Luthien, the immortal Elven princess, is referred to by Tevildo, Prince of Cats, as “Princess of Fairies”. After being ordered to dance before him by the dark lord Melkor, Luthien began

“Such a dance as neither she nor any other sprite or fay or elf danced every before or has done since… magically beautiful as only Tinuviel ever was… and Ainu Melko for all his power and majesty succumbed to the magic of that Elf-maid, and indeed even the eyelids of Lorien had grown heavy had he been there to see” (76).

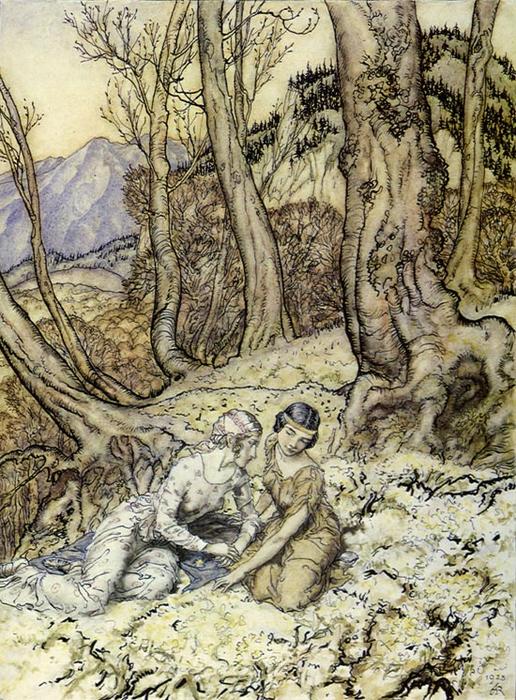

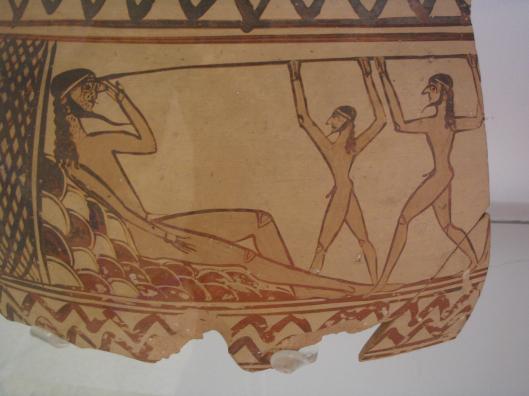

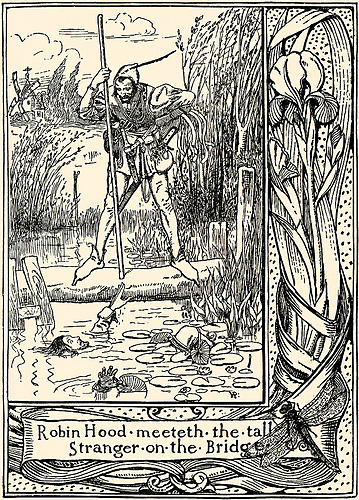

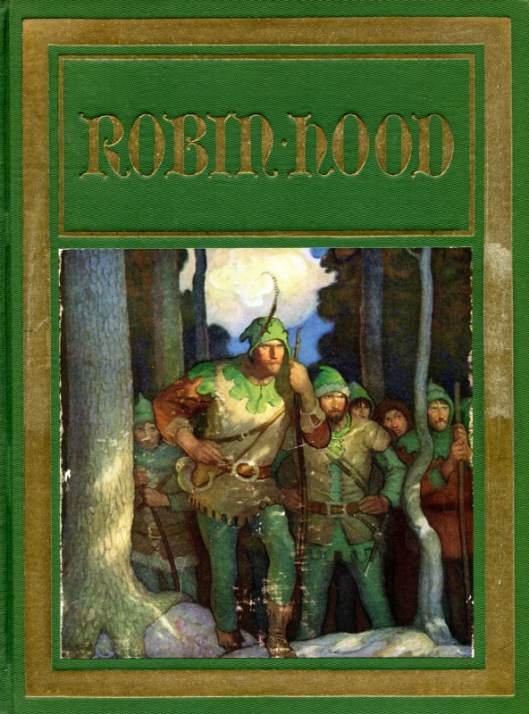

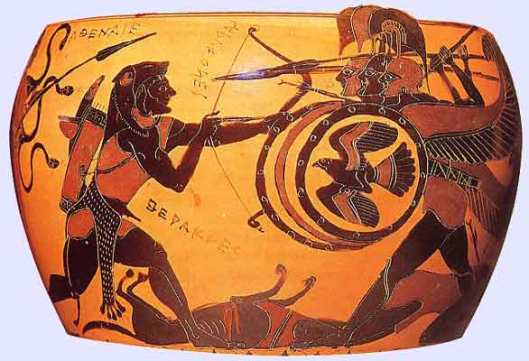

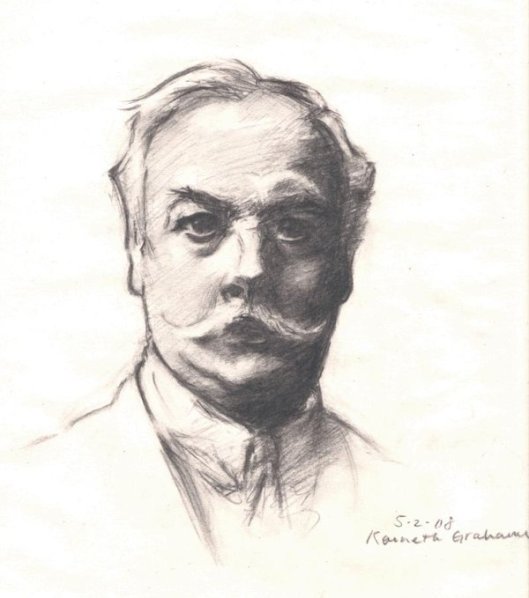

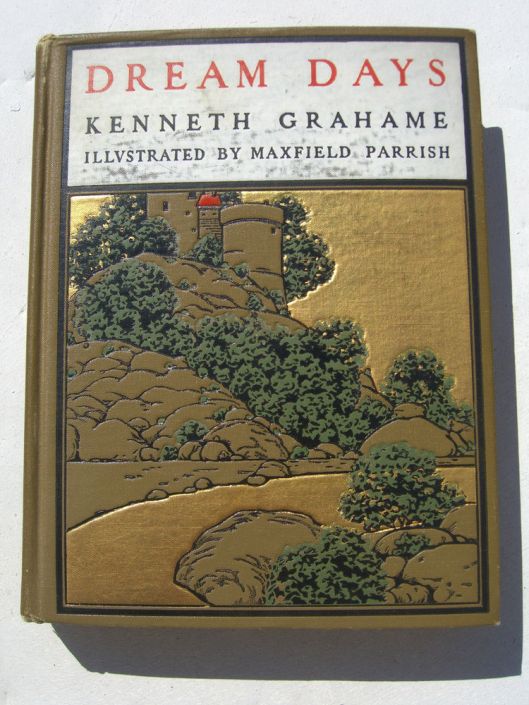

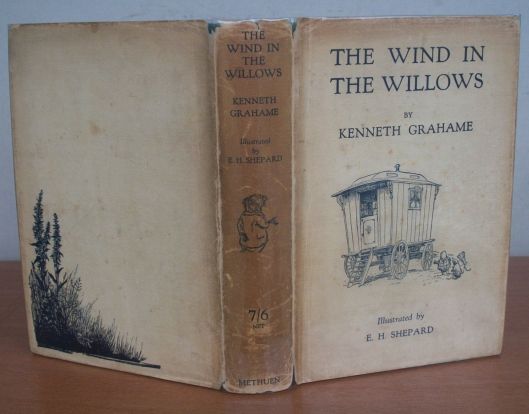

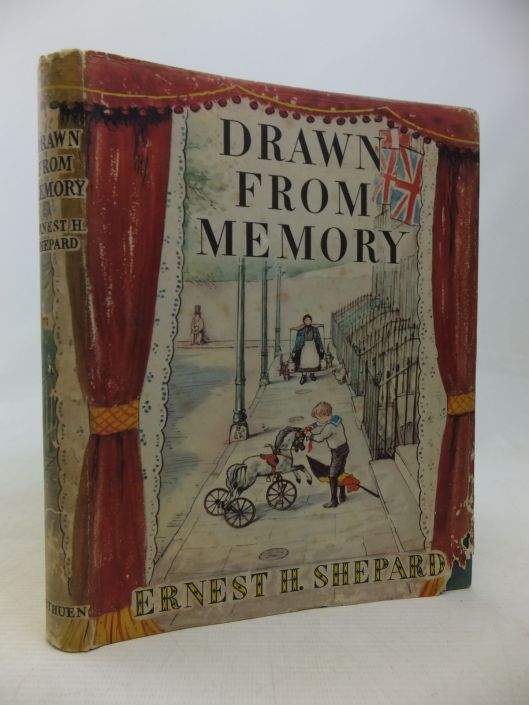

What we found curious here was JRRT’s uses of “Elf” and “Fairy” as seemingly synonymous with each other, when, depending on to which story an Elf or Fairy belongs, they may be quite different. Being people who spend a good deal of time in the Victorian world, when we think of dancing fairies, what is more likely to come to mind are the tiny winged figures who appear in Kenneth Grahame’s Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens (1906), with illustrations by Arthur Rackham.

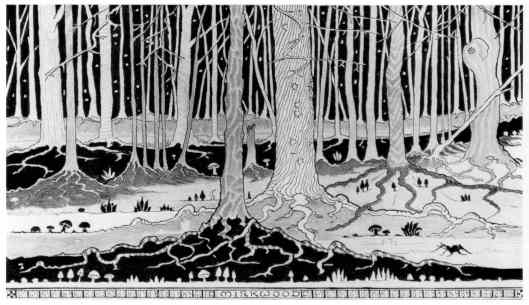

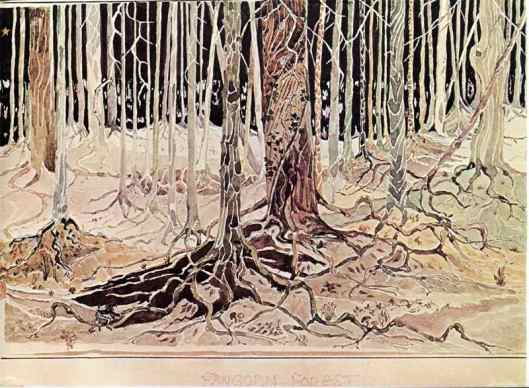

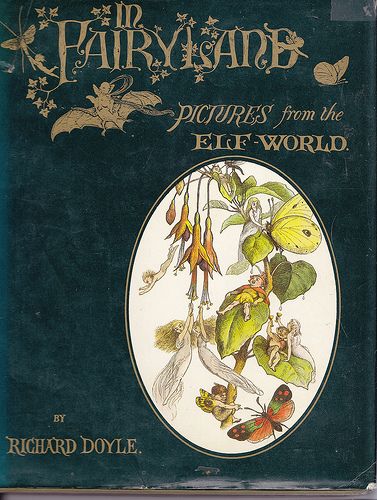

We might also be reminded of the little people who inhabit Dicky Doyle’s In Fairyland (1869)

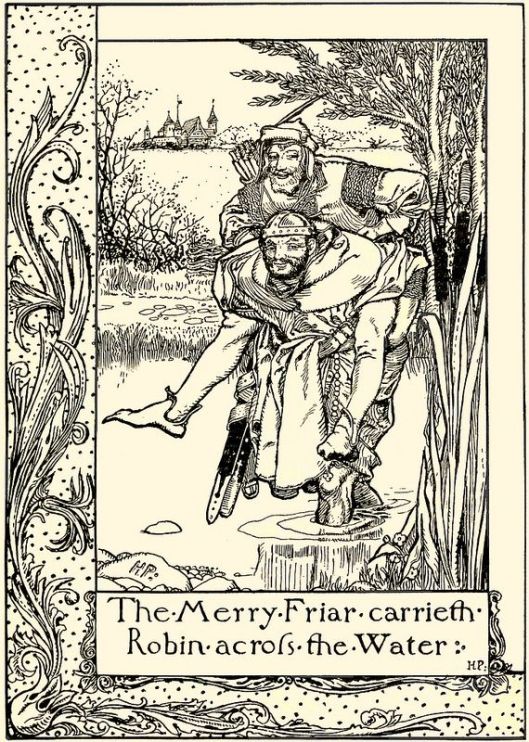

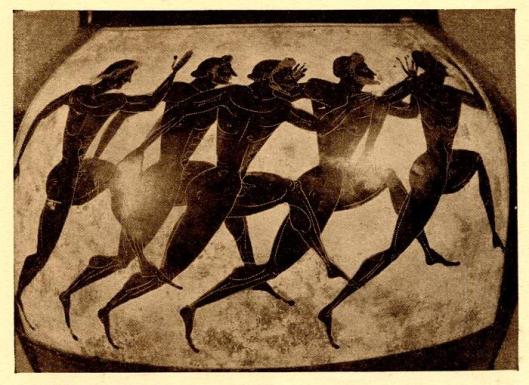

What we see in the Victorian sense of fairies and elves in images and stories is a revival of Elizabethan fairy-stories, which focus on little people: much like the fairies of William Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream, for example, the fairies in Kensington are light-footed, winged beings who wear flowing garments, and they fancy calling themselves “dancey” rather than “happy”.

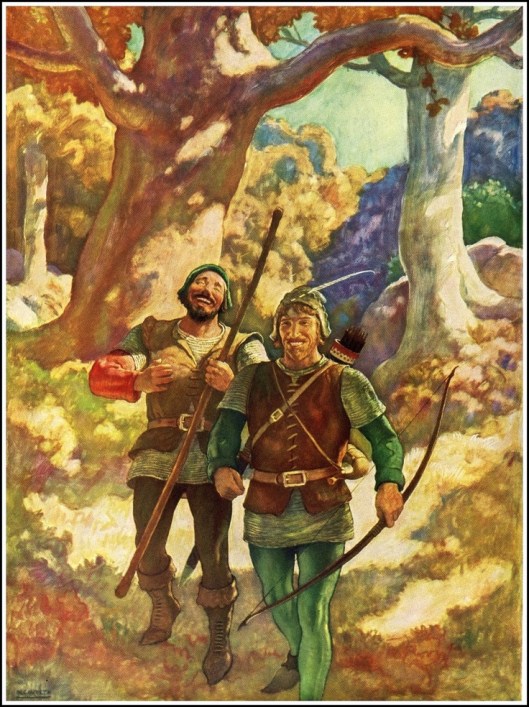

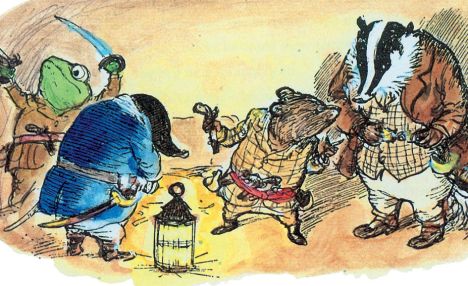

Dicky Doyle’s In Fairyland finds Elves in the “Elf World” to be the same sort of creatures. The picture below gives us an idea of the jovial nature of Victorian Elves, and is captioned, “The little Elves would cross over the border, and come into the King’s fields and gardens.”:

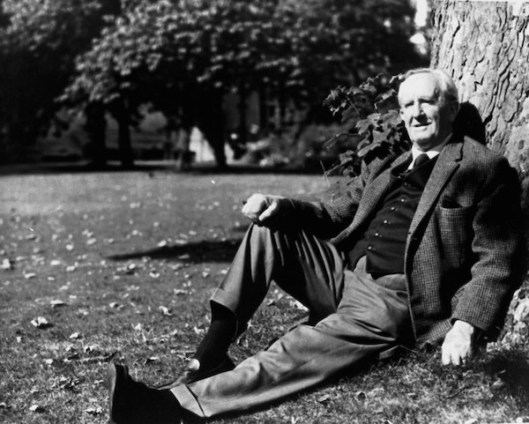

J.R.R. Tolkien was born in 1896, at the end of the Victorian period. It would be understood if the Victorian sense was residual in his work– after all, he was a child when Arthur Rackham’s illustrations met the height of their popularity, at the beginning of the 20th century, and he mentions in his letters having seen them.

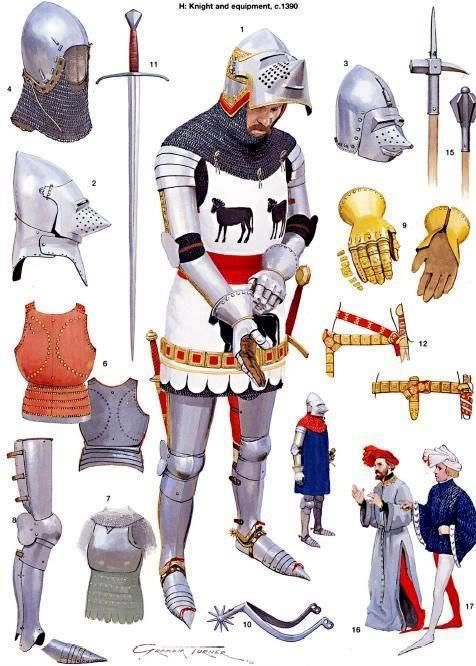

In his Middle-earth, however, we see a very different kind of Elf. Tolkien describes how he imagined them in a letter to Naomi Richardson on 25 April 1954:

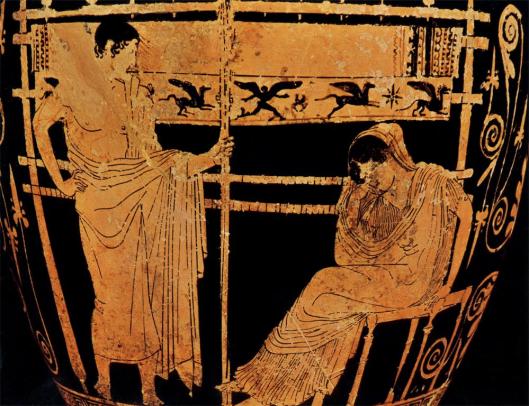

” ‘Elves’ is a translation, not perhaps now very suitable, but originally good enough, of Quendi. They are represented as a race similar in appearance (and more so further back) to Men, and in former days of the same stature… [they] are in fact in these histories very little akin to the Elves and Fairies of Europe; and if I were pressed to rationalize, I should say that they represent really Men with greatly enhanced aethetic and creative features, greater beauty and longer life, and nobility…” (Letters, 176).

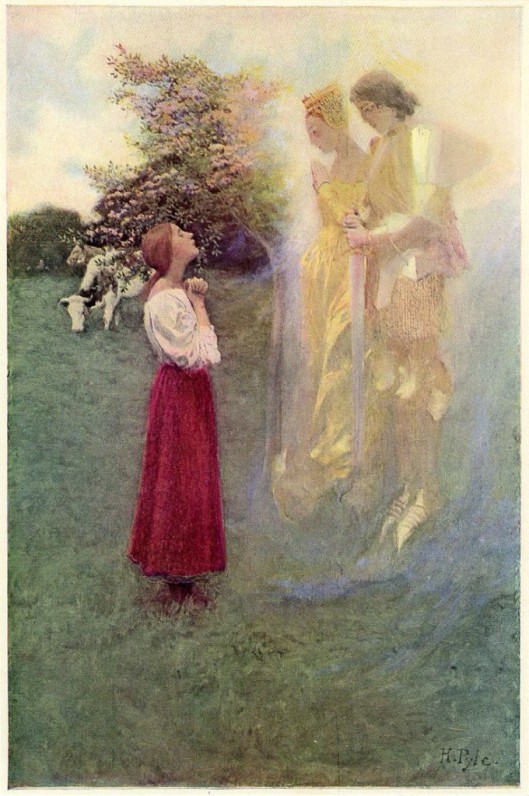

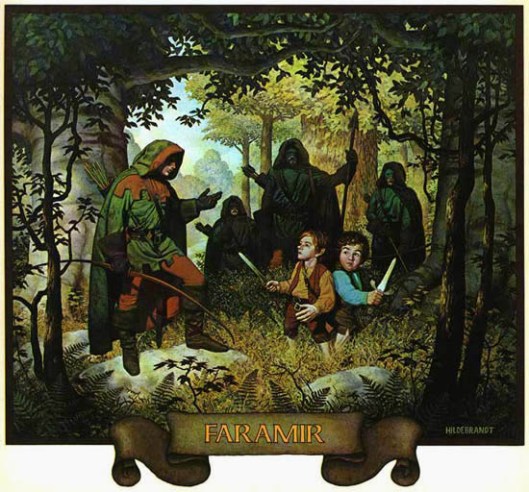

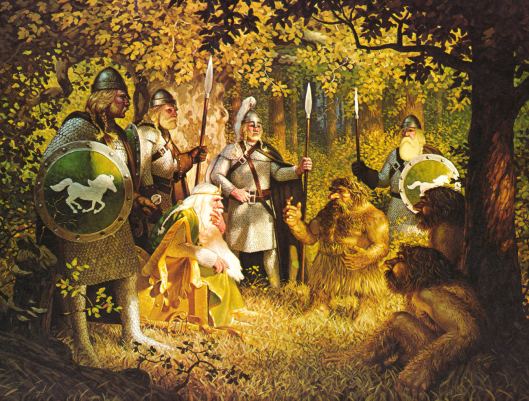

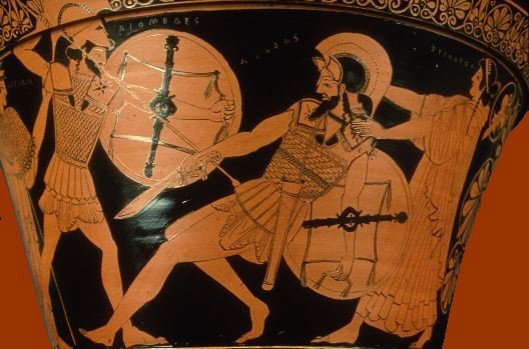

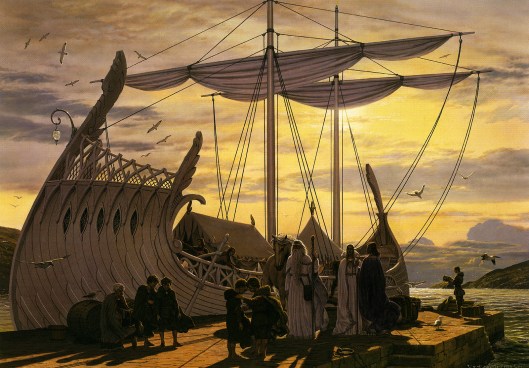

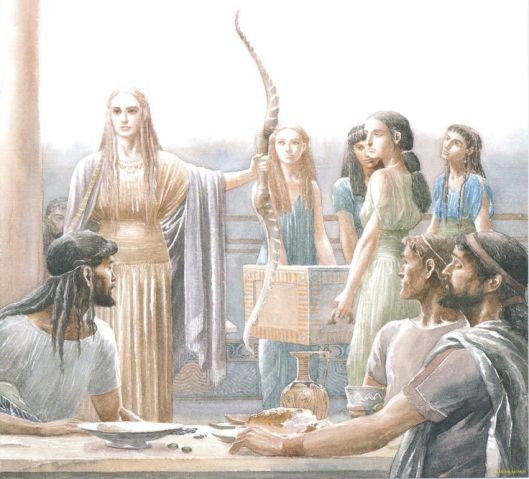

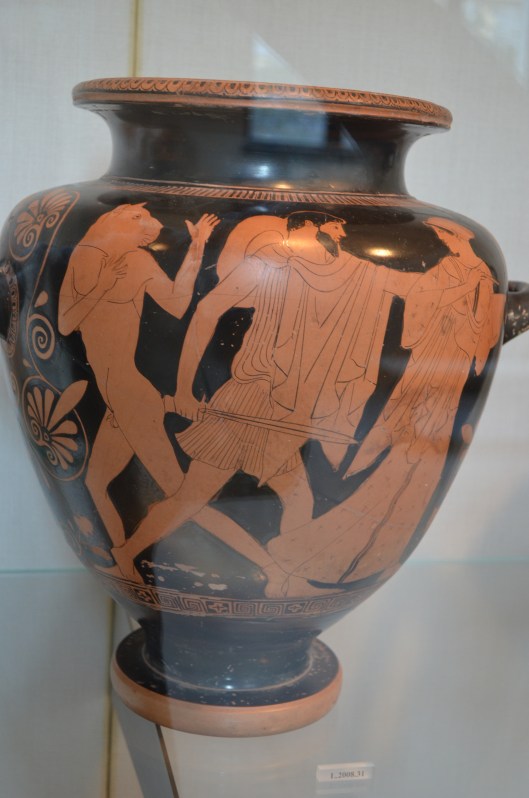

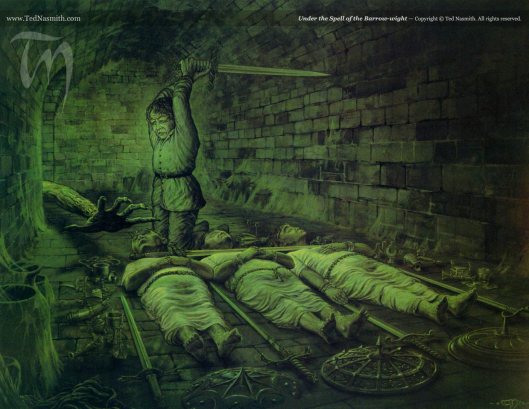

Below are a few artists’ renditions of what these Elves might look like, and they’re very different from the imaginations of Arthur Rackham and Dicky Doyle.

And some images from Peter Jackson’s films, as well:

When JRRT refers to “the former days”, we can assume that he means two things:

- The former days of Middle-earth, such as in The Silmarillion

- The former days of our world–specifically, Anglo-Saxon Elves, which resemble the Elves of Middle-earth in their stature and beauty. Thus, the “former days” refer to a former rendition of Elves– one which, belonging to the Anglo-Saxons, would be familiar to JRRT.

(Attached here is a very useful book on this subject by Alaric Hall, which provides an in-depth look at pre-Elizabethan and pre-Victorian Elves.)

These Elves are almost the polar opposite of the Elfin and Fay creatures of the Victorians, and we found it curious that they would have anything in common. As demonstrated by Rackham’s “dancey” fairies and Luthien in Beren and Luthien, however, we found one thing: a love for song and dance.

While looking through Jack Zipes’ collected anthology of Victorian Fairy Tales, The Revolt of Fairies and Elves, we came across an example of this in “Charlie Among the Elves”, in which the protagonist, a young boy who finds himself, by some sort of magic or dream, in the world of fairies and elves. The elves invite him in and greet him with a song:

“…they struck up a melody which Charlie thought was the very sweetest music which he had ever heard in the whole course of his life, and thus ran the song of the Elves:

In the waning summer light

Which the hearts of mortals love

’Tis the hour for elfin sprite

Through the flow’ry mead to rove.

Mortal eyes the spot may scan,

Yet our forms they ne’er descry;

Though so near the haunts of man,

Merrily our trade we ply.”

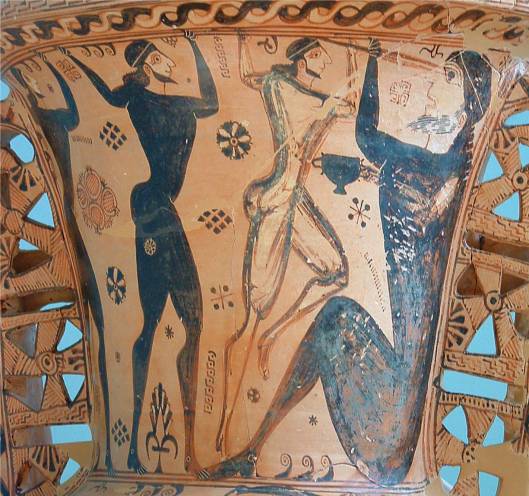

In some folklore, there is also the danger of dance. Fairy rings, also called elf rings, are supernatural places created by the dancing of either fairies, elves, or witches. They have been considered hazardous by much of Western folklore to those outside of the fairy world; in these stories, mortals who have stepped inside have been cursed, trapped, or simply disappear.

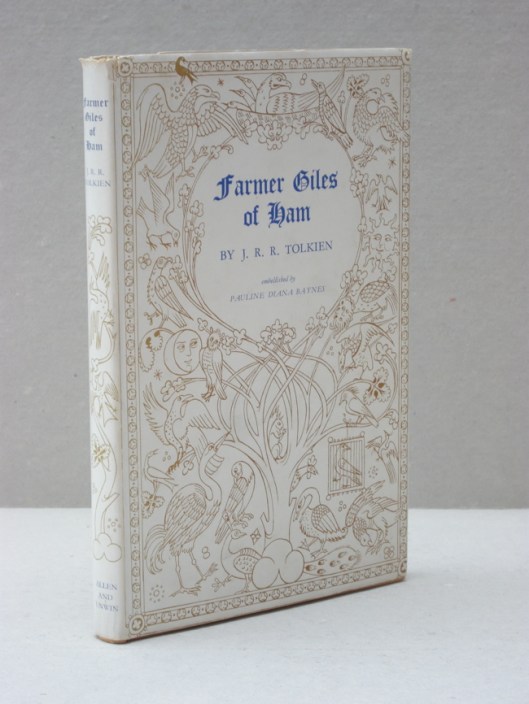

Charlie was lucky that he had come across benevolent creatures, and this reminded us of another instance when an adventurer was greeted by Elves through song: in The Hobbit, which is where Tolkien first introduced Elves, before he later understood them. Before The Lord of the Rings and The Silmarillion, Bilbo, Thorin, and Company are greeted by Elf-song in Rivendell:

” ‘Hmmm! it smells like elves!’ thought Bilbo, and he looked up at the stars. They were burning bright and blue. Just then there came a burst of song like laughter in the trees:

‘O! What are you doing,

And where are you going?

Your ponies need shoeing!

The river is flowing!

O! tra-la-la-lally,

here down in the valley!’ ”

As the Elves in both “Charlie Among the Elves” and The Hobbit are jovial and playful in their music, we might think that Tolkien had not completely abandoned the Victorian Elfin world, after all; of course, in The Lord of the Rings and in The Silmarillion, the Elves, just as much as the stories, take a more serious turn. Playful tunes are replaced with much more serious poetry, and in their native tongue, such as the Hymn to Elbereth Gilthoniel:

“A Elbereth Gilthoniel

Silivren penna miriel

A menel aglar elennath

Na chaered palandiriel.

O Galadhremmin ennorath

Fanuilos, le linnathon

Nef aer, si nef aeron!

A Elbereth Gilthoniel!

We still remember,

We who dwell

In the lands beneath the trees

Thy starlight on the western seas.”

When trying to reconcile these sorts of Elves and Fairies, rather than assessing them through their physical and behavioral qualities, we may look at them through something just as important in understanding them: music. The Silmarillion explains that the Elves, as well as the world and everything in it, including good and evil, originated from song.

But just as Elven music changes from The Hobbit to The Lord of the Rings, so the Elves have changed– they are human-sized, but also perhaps more serious and melancholy, as a parallel to the world Tolkien had created, which was much more complex than he originally realized.

The songs in The Lord of the Rings, and the later versions of Luthien, which present her as an Elf princess– a beautiful being which Beren falls in love with as soon as he sees her dance– express that melancholy. As the tale of Beren and Luthien reflects the way Tolkien wishes us to see Elven folklore– romantic, adventurous, and, ultimately, sorrowful– perhaps we can conclude that JRRT’s Elves are really fairies grown up.

And what do you think, dear readers?

MTCIDC,

CD

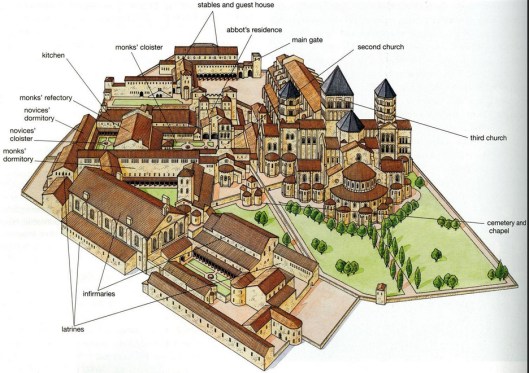

In our medieval world, such bells had a number of functions. Not only did they ring the hours of the medieval Christian day, but they could also sound a warning, called the “tocsin”, and signal that the day was over and that fires should be covered for the night, the “curfew”—rather like the “sun-down” bells in Minas Tirith. Joan of Arc (c.1412-1431) said that she could sometimes hear the sound of angelic voices, inspiring her to drive the English out of France, in her village bell.

In our medieval world, such bells had a number of functions. Not only did they ring the hours of the medieval Christian day, but they could also sound a warning, called the “tocsin”, and signal that the day was over and that fires should be covered for the night, the “curfew”—rather like the “sun-down” bells in Minas Tirith. Joan of Arc (c.1412-1431) said that she could sometimes hear the sound of angelic voices, inspiring her to drive the English out of France, in her village bell.