Welcome, dear readers, as ever.

We had what we thought was a very interesting idea for this posting—about the effect of a Morgul-knife and that of something from western European—perhaps specificially Germanic?—folk tradition, an “elf shot”.

“Elf shot” was once thought to be a condition in humans and animals, caused by an arrow fired by someone from the Otherworld. There was a long tradition of methods of healing, which could be a difficult problem because the entry wound might be nearly—if not completely—invisible and it took special skills to find it and to remove the arrowhead, while, in the meantime, the victim slowly withered away.

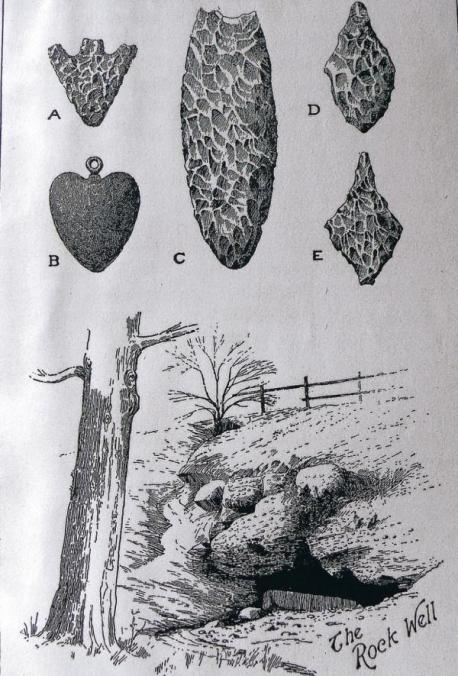

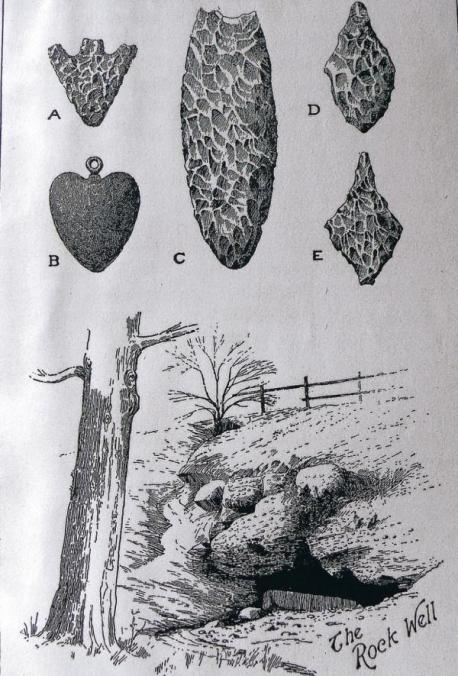

When it was supposedly removed, by someone who was believed to have competence in such matters, the arrowhead was probably actually a Neolithic point, like one of these—

picked up from somewhere and whatever had actually caused the withering was a disease brought on in the natural order of things, but all of the stories we’ve read about the belief and cures appear to end with the point removed—and the sufferer in recovery.

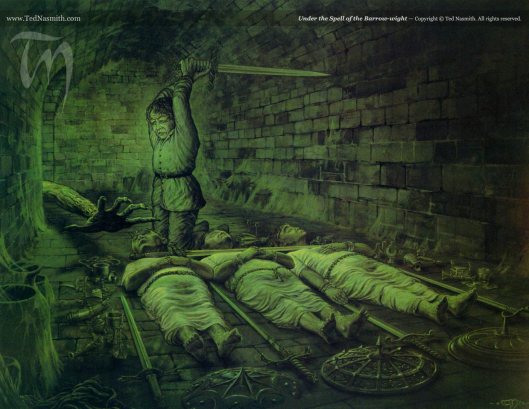

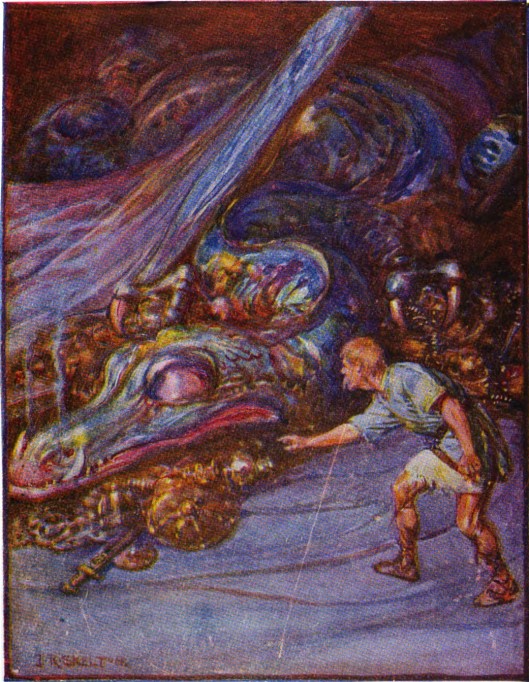

Hmm—we thought. Something familiar about this. On Weathertop, Frodo is attacked by Nazgul.

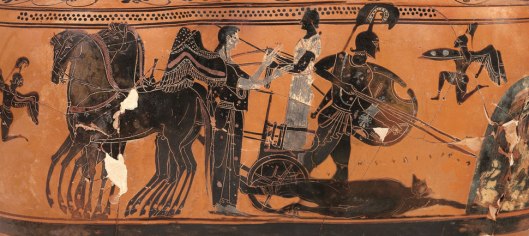

“The third was taller than the others: his hair was long and gleaming and on his helm was a crown. In one hand he held a long sword, and in the other a knife; both the knife and the hand that held it glowed with a pale light. He sprang forward and bore down on Frodo.” (The Fellowship of the Ring, Book One, Chapter 11, “ A Knife in the Dark”)

The figure stabs Frodo, but the weapon which did it was no ordinary one, as Strider indicates, lifting

“…up a long thin knife. There was a cold gleam in it. As Strider raised it they saw that near the end its edge was notched and the point was broken off. But even as he held it up in the growing light, they gazed in astonishment, for the blade seemed to melt, and vanished like a smoke in the air, leaving only the hilt in Strider’s hand.” (The Fellowship of the Ring, Book One, Chapter 12, “Flight to the Ford”)

In the film, this is represented by something which looks like a medieval fighting dagger.

It seems that its purpose was not to act as a secondary weapon in combat, however, but to inflict a fatal stabbing wound. As Gandalf says,

“They tried to pierce your heart with a Morgul-knife which remains in the wound.” (The Fellowship of the Ring, Book Two, Chapter 1, “Many Meetings”)

Thus, we could imagine it looking like a Renaissance poignard, like this one—

Whatever its look, its point is embedded in Frodo’s shoulder and, like someone elf-shot, Frodo is fading and, also like the victim of elf-shot, the wound has changed.

“ ‘What is the matter with my master?’ asked Sam in a low voice, looking appealingly at Strider. ‘His wound was small, and it is already closed. There’s nothing to be seen but a cold white mark on his shoulder.; “ (The Fellowship of the Ring, Book One, Chapter 12, “The Flight to the Ford”)

Neither Strider nor, in turn, Glorfindel, can heal Frodo and even Gandalf was daunted:

“Elrond is a master of healing, but the weapons of our Enemy are deadly. To tell you the truth, I had very little hope; for I suspected that there was some fragment of the blade still in the closed wound. But it could not be found until last night. Then Elrond removed a splinter. It was deeply buried, and it was working inwards.” (The Fellowship of the Ring, Book Two, Chapter 1, “Many meetings”)

We thought, then, that we could write a very interesting post about the parallels between that knife and elf-shot—and then we found that it had already been done: see “Elf-shot” in Drout, Michael, ed., J.R.R. Tolkien Encyclopedia, London: RKP, 2006.

We are not given to despair, however, and something Gandalf said interested us: “Then Elrond removed the splinter.”

As our regular readers know, we take particular pleasure in linking things of Middle-earth with those of the medieval world in which JRRT spent his scholarly life. In this case, we were reminded of the removal of part of another weapon—the head of an arrow (just like elf-shot) from the head of a real person: Prince Henry of England—the future Henry V (1386-1422) of Shakespeare’s wonderful play. (We grew up on the 1944 Laurence Olivier version, which is full of color and action—the reconstruction of the Globe Theatre at the opening alone is worth watching—although, as we’ve gotten older, we’ve come to prefer both Kenneth Branagh’s 1989 filming and the 1979 David Gwillim version which we mentioned in our last posting.)

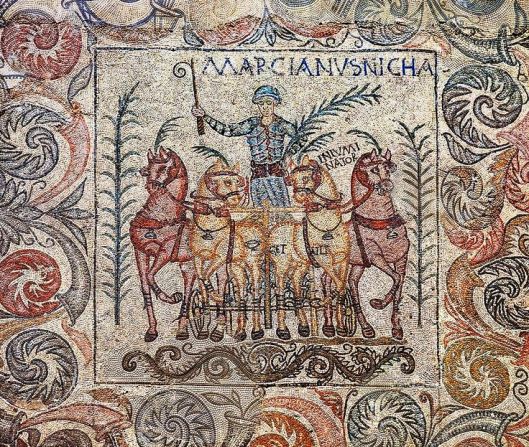

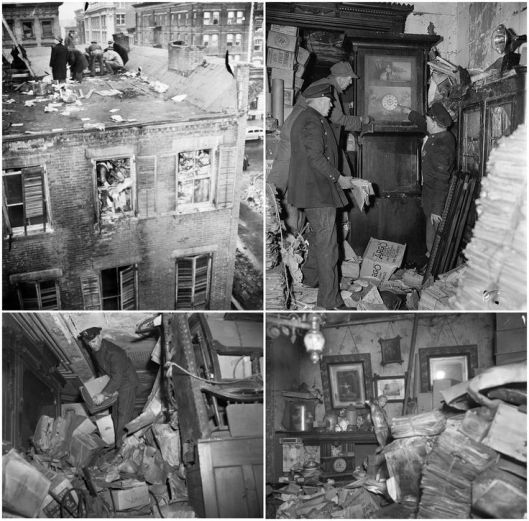

When he was fifteen, Prince Hal commanded the left wing of his father’s army at the battle of Shrewsbury, on 21 July, 1403.

(Note: this is an old map, based upon the tradition that the church of St. Mary Magdalen was built on the site of the battle.

In 2006, the Anglo-Scots archaeologists, Tony Pollard and Neil Oliver, led a team to probe the churchyard, where it had long been held that there was a burial pit for some of the dead of the battle. After geophysical exploration and the digging of several test trenches, no trace of such a pit was found, leaving the tradition to remain, at least for the moment, just that. If you are interested to learn more, their visit to the site is from their 2-year series, Two Men in a Trench. Here’s a LINK—you can watch the whole show—and we recommend the entire series for a combination of light-hearted looniness and serious archaeology.)

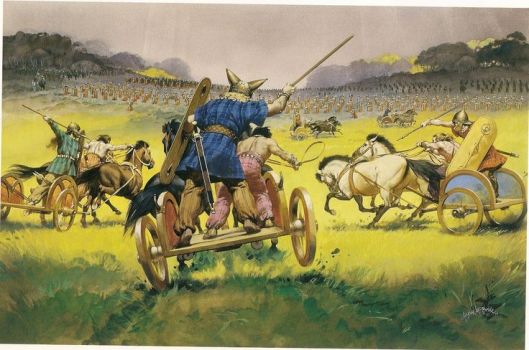

The battle began with a barrage of arrows from the longbowmen on each side.

The arrows had what were called bodkin points—

which were specifically designed to penetrate plate armor of the very sort which the prince was wearing.

A practiced longbowman could fire ten arrows a minute and his original battlefield issue would have been two 24-arrow linen bundles. We don’t know how many archers both sides had, but even if each had no more than a thousand, at the end of in a single minute, that would have meant 20,000 arrows in the air.

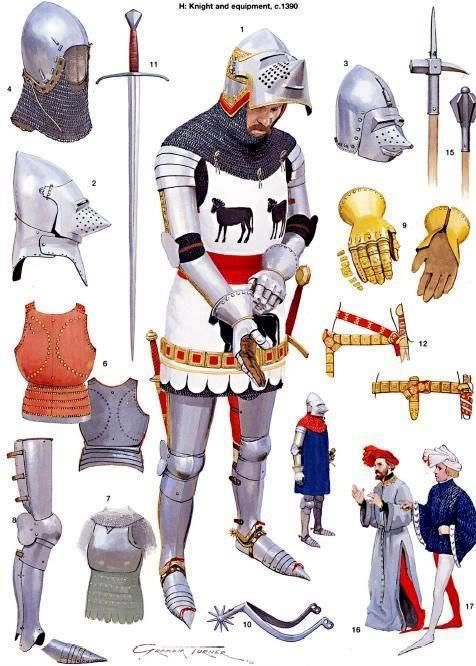

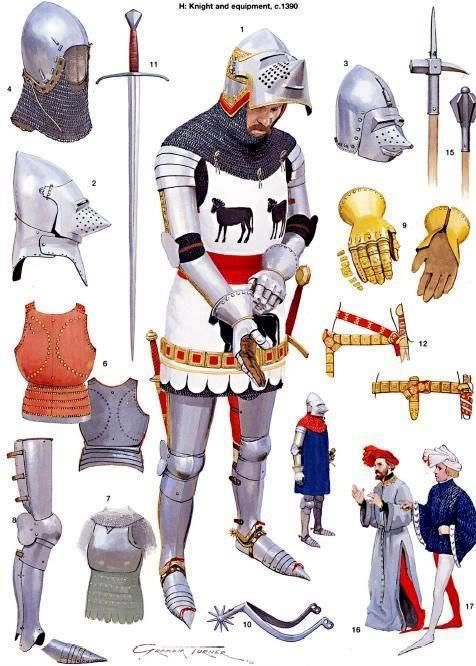

If Hal was wearing a bascinet—as you see on the knight above–because of the shape of the helmet, many of the arrows might have glanced off. Perhaps Hal was wearing an open-face bascinet

or had raised his visor, to give a command, say, but, instead of bouncing off, an arrow hit him in the face, below his eye (there is argument as to which eye) and penetrated his head. Had it gone all the way through, it might have been possible to saw off the arrow head and remove both arrow and shaft, but the arrow head had sunk into the bone at the back of the skull, instead. (Remarkably, it is reported that Hal continued to direct his troops, even in this condition. Tough people, those medievals!) And the first attempt at extraction had broken off the shaft, leaving the arrowhead still embedded. And this, of course, is what made us think of Elrond and the Morgul-knife splinter.

We aren’t told how Elrond found or removed it. A medieval tool for removing arrowheads had been invented by the brilliant Arab physician with the splendid name of Abu al-Qasim Khalaf ibn al-Abbas al-Zahrawi, reduced by westerners to “Albucasis” (936-1013). (Here’s a LINK—this is a man of science well worth knowing much more about!)

This might have worked, had the arrow been in a less delicate place, as well as not barbed, but Hal’s wound was just below his brain stem and next to all sorts of delicate blood vessels and the arrowhead was a bodkin point.

At this point, John Bradmore appeared. Interestingly, he had been a goldsmith, as well as a practicing surgeon, and the two seem to have come together as he tackled the problem. First, while he considered the possibilities, he kept the wound open and cleaned. Then he invented this—

It’s a simple but cunning design: the two outer parts are gradually introduced into the wound and spread it gently open. In the middle is a screw mechanism which could insert itself into the socket of the arrowhead. When it is firmly in place, the outer parts are closed as far as possible and then the whole, with, Bradmore hoped, the arrowhead, could be extracted from the wound. And it was. And then Bradmore washed out the wound with wine and kept it clean during the healing process. A completely remarkable piece of work, from the use of antisepsis to the invention and manufacture of the necessary tool.

Hal not only survived the operation (he had reportedly been dosed with henbane, which would have stupefied him but, given the wrong dose, would have killed him within a couple of days), but lived another 19 years to beat the French at Agincourt, marry the daughter of the king of France, and, for a brief time, imagine seeing his son succeed him on the now-joint thrones.

As for Bradmore, he wrote a medical treatise, Philomena, the title being a learned joke– St. Philomena was an early Christian martyr, part of whose martyrdom included surviving arrow attacks—before dying, a very well-off man, in 1412.

(If you’d like to see a very well-done visual segment on Bradmore and Prince Hal, here’s a LINK for a NOVA program of some years ago.)

In both cases, the patient survived, although it would appear that Prince Hal had a better recovery than Frodo. Then again, Hal, for all that his wound was life-threatening, hadn’t been hit by an elf-shot, but only by a mortal arrow, while the hobbit was almost doomed to the Nazgul world by a Morgul-knife.

Thanks, as ever, for reading.

MTCIDC

CD

PS

One of our favorite Danish composers, Niels W. Gade (1817-1890), has left us a very beautiful dramatic cantata, Elverskud—“Elfshot” (1854). Based upon a Danish ballad, it’s the story of Sir Oluf, who prefers the Elf king’s daughter to his own human bride and the consequences of that preference. If you’d like to hear it—we recommend it and much other music by Gade, as well—here’s a LINK.

PPS

This posting is our 151st! Five more will make exactly three years of weekly postings. Thank you for reading, and we hope to keep you interested for another 150 postings at least.