Tags

Abd el-Ouahed ben Messaoud ben Mohammed Anoun, Algiers, Anduin, Barbary Coast, buccaneer, corsair barbary, Corsairs, draught, dromon, dromunds, galley, Harad, Haradrim, Harlond, Helm's Deep, Legatus Regis Barbariae, Pelennor, Pirates, Ramas Echor, Southrons, The Lord of the Rings, Tolkien, Turkish galley, Umbar, US Navy WW2 fighter

Welcome, dear readers, as always.

In a previous posting, we mentioned the Corsairs of Umbar.

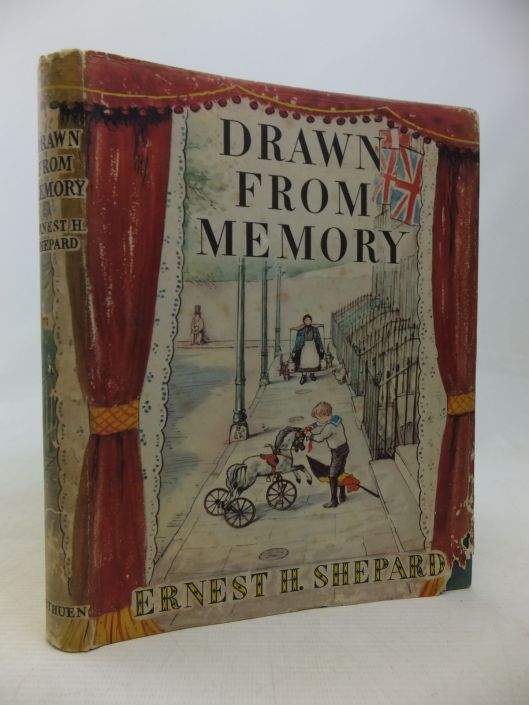

If you google “corsair” in images, the first thing which appears is this:

It’s a US Navy WW2 fighter—but hardly what was sweeping to attack the south coast of Gondor in Sauron’s massive campaign.

Change that to “corsair pirate” and you see things like

which is definitely a bit better, but he looks so 18th-century. As we have discussed in many of our postings, Middle-earth is Middle Ages (more or less), even if it mixes High Medieval (things like the plate armor of the Prince of Dol Amroth) with Anglo-Saxon (the Rohirrim). So “corsair pirate” is too late in time. Another word (with a much-discussed origin) for “pirate” is “buccaneer”, so, how about “corsair buccaneer”?

Ooops! Okay—clearly that doesn’t work!

So what will—and what are we really looking for? Well, what do these corsairs look like according to JRRT?

They have black sails:

For Anduin, from the bend at the Harlond, so flowed that[,]from the City[,] men could look down it lengthwise for some leagues, and the far-sighted could see any ships that approached. And looking thither they cried in dismay; for black against the glittering stream they beheld a fleet borne up on the wind: dromunds, and ships of great draught with many oars, and with black sails bellying in the breeze.

‘The Corsairs of Umbar!’ men shouted. (The Return of the King, Book Five, Chapter 6, “The Battle of the Pelennor Fields”)

Anything more?

In The Lord of the Rings, unfortunately not.

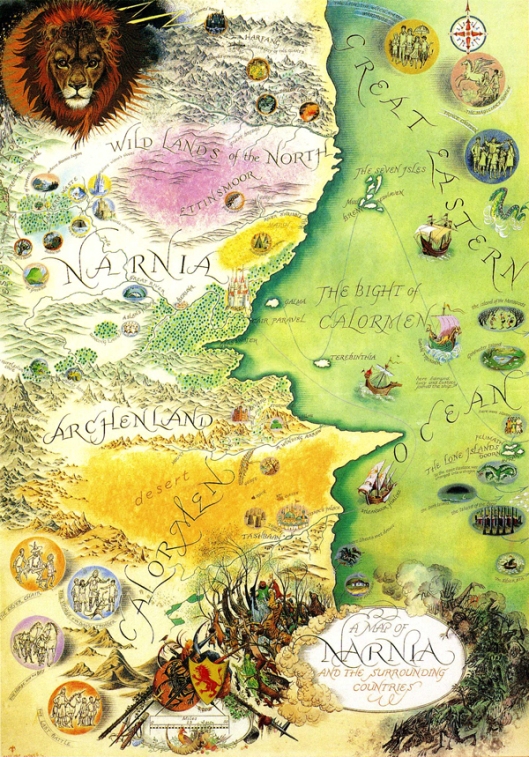

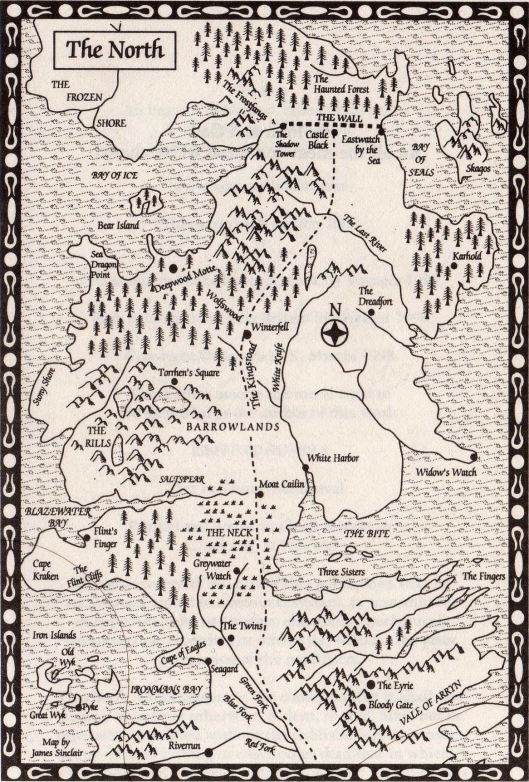

Umbar is in Harad,

however, and there is a little about the Haradrim. Our first view of them is Sam’s:

Then suddenly straight over the rim of their sheltering bank, a man fell, crashing through the slender trees, nearly on top of them. He came to rest in the fern a few feet away, face downward, green arrow-feathers sticking from his neck below a golden collar. His scarlet robes were tattered, his corselet of overlapping brazen plates was rent and hewn, his black plaits of hair braided with gold were drenched with blood. His brown hand still clutched the hilt of a broken sword. (The Two Towers, Book Four, Chapter 4, “Of Herbs and Stewed Rabbit”)

Other details?

Just before Sam speaks, Gollum has reported seeing:

‘Dark faces. We have not seen Men like these before, no, Smeagol has not. They are fierce. They have black eyes, and long black hair, and gold rings in their ears; yes, lots of beautiful gold. And some have red paint on their cheeks, and red cloaks; and their flags are red, and the tips of their spears; and they have found shields, yellow and black with big spikes. Not nice; very cruel wicked Men they look. Almost as bad as Orcs, and much bigger.’ (The Two Towers, Book Four, Chapter 3, “The Black Gate is Closed.”)

“cruel and tall” (The Return of the King, Book Five, Chapter 4, “The Siege of Gondor”)

They have cavalry and they are armed with scimitars. (The Return of the King, Book Five, Chapter 6, “The Battle of the Pelennor Fields”)

These would seem to be people from Near Harad (that is, near to Gondor). The men to the south of them differ:

“…Southrons [men from Near Harad] in scarlet and out of Far Harad black men like half-trolls with white eyes and red tongues.” (The Return of the King, Book Five, Chapter 6, “The Battle of the Pelennor Fields”)

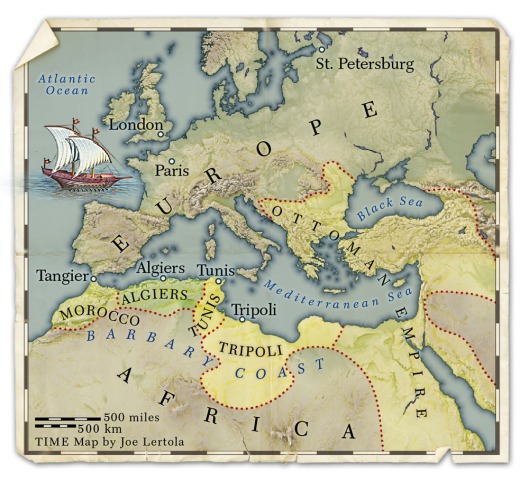

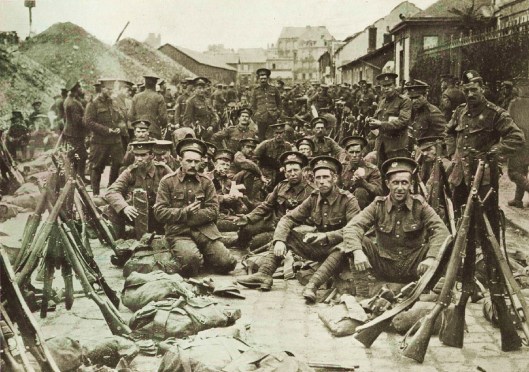

But all of this to us suggested a model from our own world (as always): the Barbary Pirates. So how about the search terms “corsair barbary”?

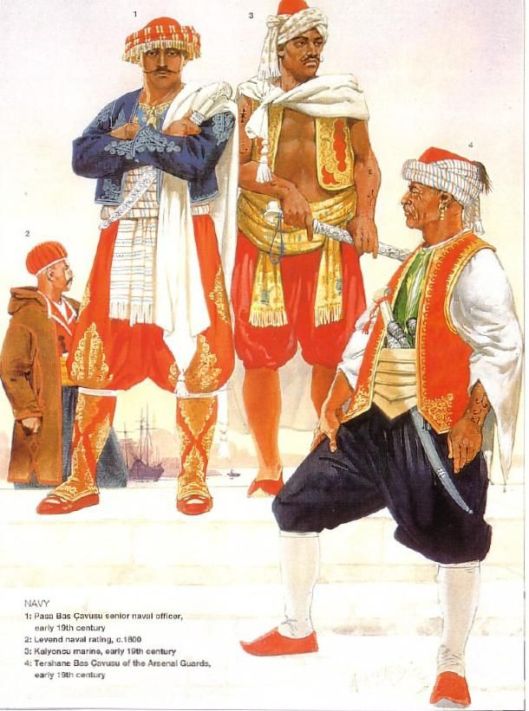

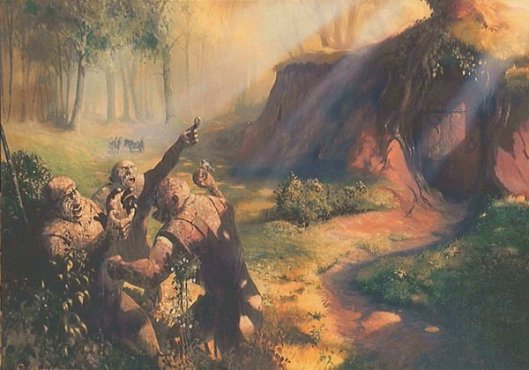

Ah. That’s a bit more like it, we think. He has to lose his gunpowder weapons, though—the only gunpowder in Middle-earth appears to be something in the hands of Saruman and Sauron’s orcs, as we see at Helm’s Deep

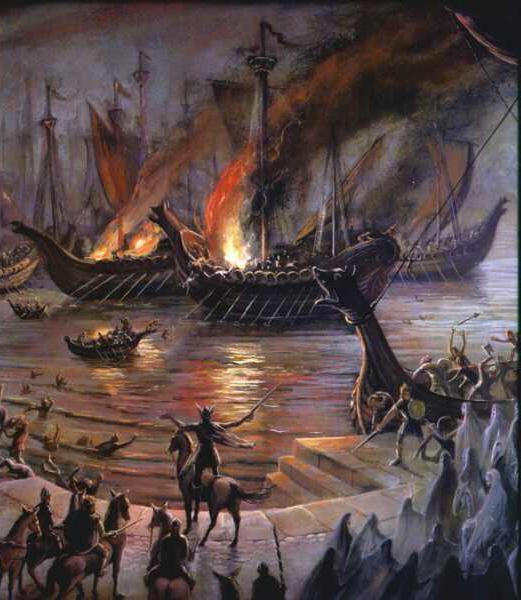

and the wall of the Pelennor, the Ramas Echor.

We would imagine those corsairs, then, as looking like the infamous “Barbary Pirates”.

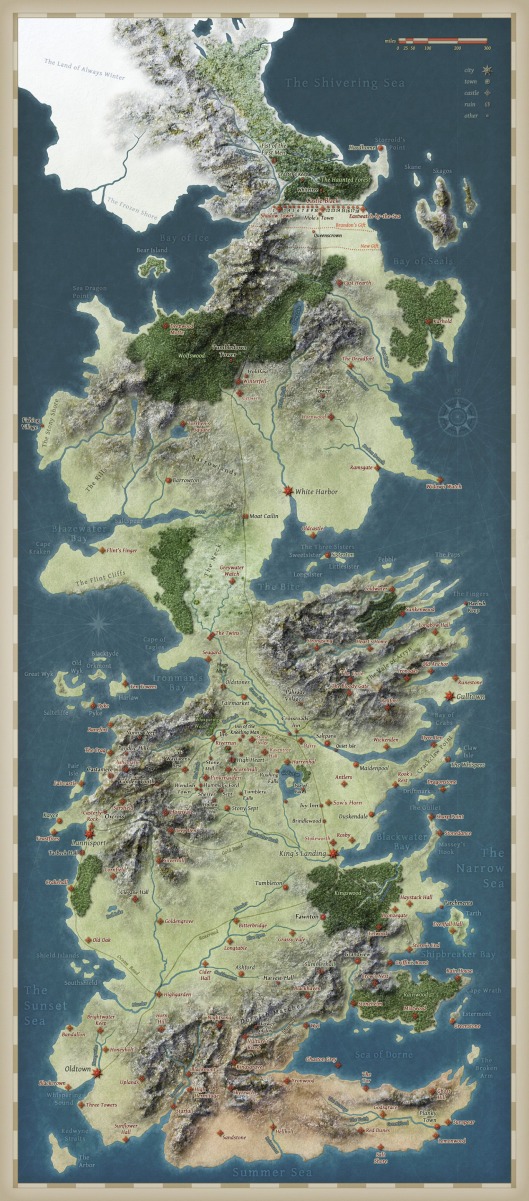

They certainly fill the bill geographically—they’re southern (at least in relation to JRRT’s England)–their hangouts being on the coast of North Africa

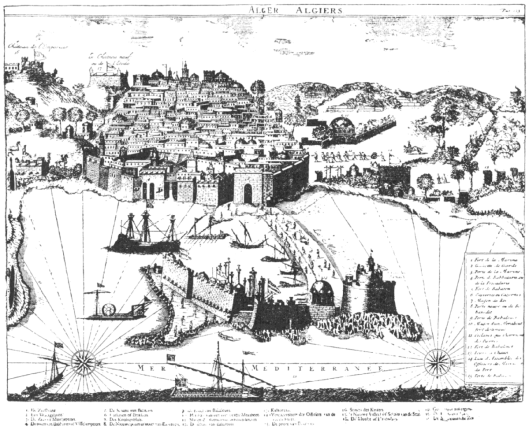

and, if you wanted a big port city, as Umbar was supposed to be, here’s Algiers.

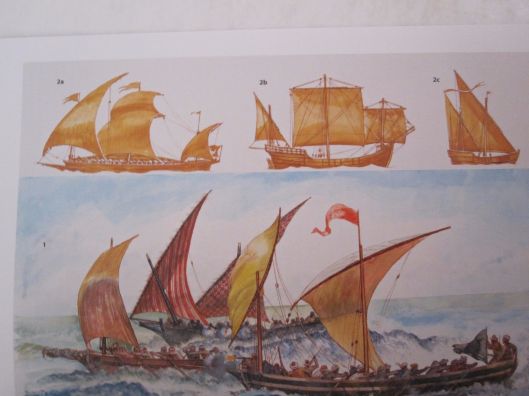

What about ships—that is, “dromunds and ships of great draught with many oars”?

“Dromund” is a medieval form of the Byzantine Greek dromon, literally a “runner”—a word you’d recognize from the English word “hippodrome”—the “place where horses run”. This was the common larger Byzantine warship.

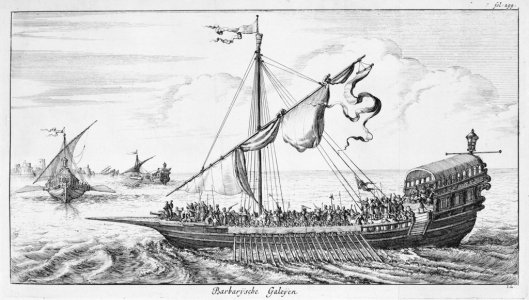

Here’s a Renaissance-era engraving of a Turkish galley.

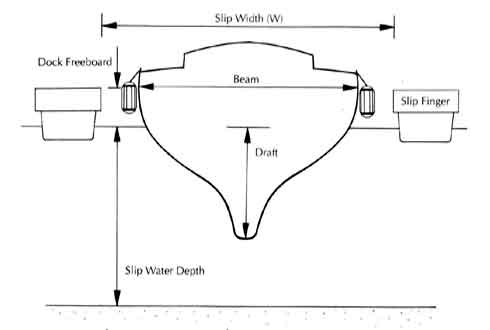

There’s a difficulty with “ships of great draft with many oars”, however. Draught (also spelled “draft”) is the distance between the waterline and the bottom of the keel, as in this diagram.

Ships with many oars are, commonly, galleys,

and galleys commonly have a shallow draft—both to allow for maneuver in shallow waters and to allow for the oars to do their job most efficiently. So, we presume that all of the Corsairs’ vessels were actually galleys of various sizes.

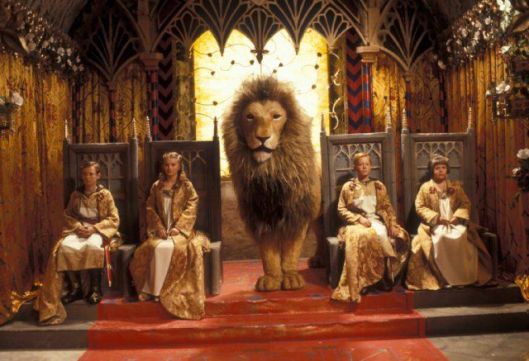

Jackson’s Corsair ships have something of the look of JRRT’s description, but his

depiction of the Corsairs, unlike that of Rohan and the Rohirrim, is not even close to the little we have learned so far from the text.

The Barbary Pirates, to us, not only match point of origin and vessels, but are much more exotic and colorful, whereas those in the film look to us more like dingy Vikings.

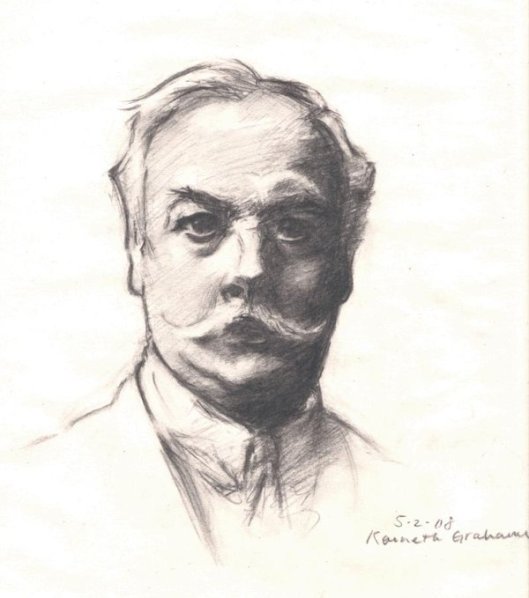

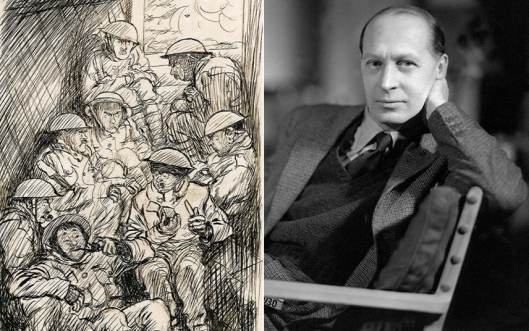

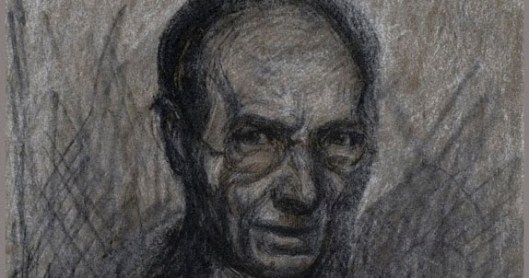

And here’s a portrait

of the Moroccan ambassador to the court of Queen Elizabeth I (notice that, in the caption he’s called Legatus Regis Barbariae, “deputy of the King of Barbary”—a splendid figure with a splendid name: Abd el-Ouahed ben Messaoud ben Mohammed Anoun—imagine him facing Aragorn from the deck of a galley—we think that the Oath-breakers would have had little fear for him, even as they overwhelmed him and his crew.

So, as always, we ask you, readers, what do you think?

And thanks, as always, for reading.

MTCIDC

CD

PS

Just a thought, but, if Sauron, as one of the Maiar, was virtually immortal and had the kind of power which is displayed in the forging of the Ring, why did he need vast fortresses and armies and fleets? Something to think about in a future posting!

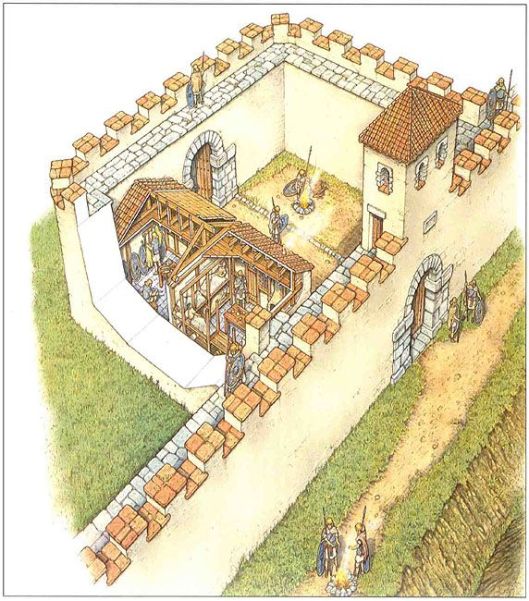

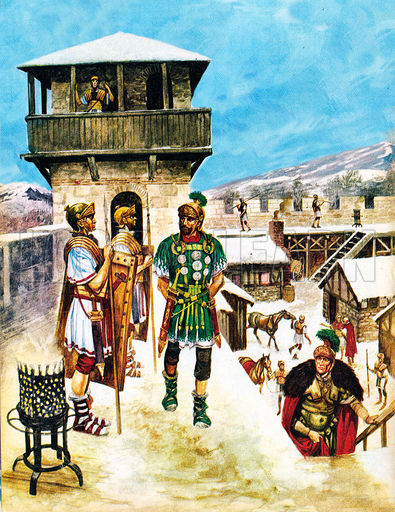

Originally, this had been the site of a Gondorian strongpoint, but, as Gondor waned, it fell into disuse until taken over by Saruman with the permission of the Steward of Gondor, Beren. When

Originally, this had been the site of a Gondorian strongpoint, but, as Gondor waned, it fell into disuse until taken over by Saruman with the permission of the Steward of Gondor, Beren. When

Like Saruman, Macbeth is overcome, gives in, murders Duncan, seizes power, but, also like Saruman, can not retain it and, interestingly, an element in his defeat closely resembles an element in Saruman’s defeat: trees.

Like Saruman, Macbeth is overcome, gives in, murders Duncan, seizes power, but, also like Saruman, can not retain it and, interestingly, an element in his defeat closely resembles an element in Saruman’s defeat: trees.

)

)