Tags

Arthur Rackham, Beowulf, C.S. Lewis, Chrysophylax, Custard the Dragon, Dragons, Dream Days, Esgaroth, Farmer Giles of Ham, Jabberwock, Jabberwock-slayer, Kenneth Grahame, Lewis Carroll, Lonely Mountain, Luttrell Psalter, map, Middle-earth, Narnia, Ogden Nash, Pauline Baynes, Rumer Godden, Smaug, St George, The Chronicles of Narnia, The Dragon of Og, The Hobbit, The Lion The Witch and the Wardrobe, The Lord of the Rings, The Reluctant Dragon, Through the Looking-Glass, Tolkien, Walt Disney

As always, readers, welcome.

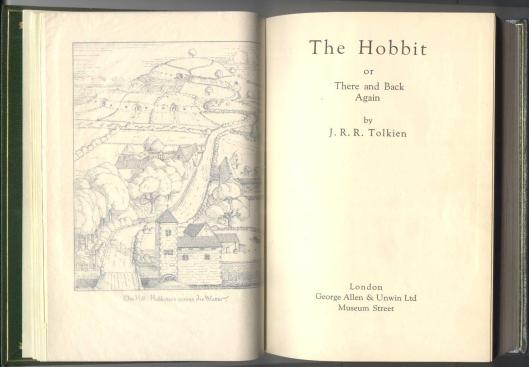

One of us is currently teaching a class where our present focus is upon The Hobbit.

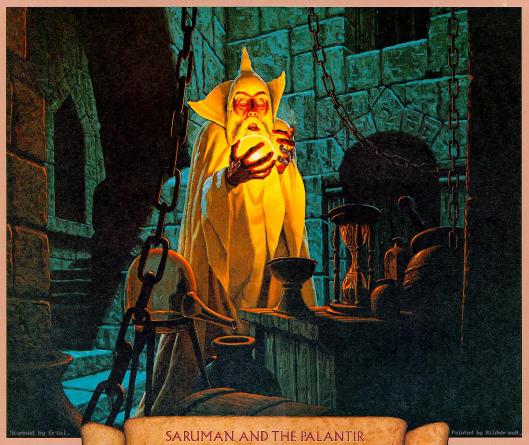

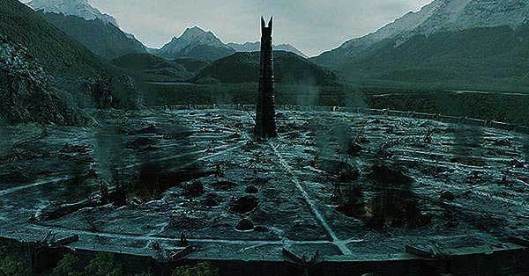

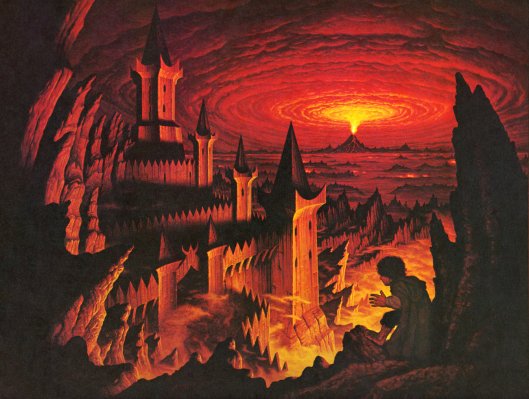

At the center of the book is the Lonely Mountain and at the center of that is Smaug.

This got us to thinking about other dragons in our experience, and some of those are not quite of the same breed as the hoard-sitter faced by Bilbo and the dwarves. That dragon is closely related to the Beowulf variety

which, unlike Smaug, has neither a name nor (it seems) human speech, but it certainly has the same suspicious streak: when an escaped slave steals a cup from its hoard, it’s almost immediately aware that it’s missing and suspects a human.

And they are both vengeful. As Smaug devastates Esgaroth, even if he dies for it,

so Beowulf’s dragon scorches the countryside in revenge for the theft.

But what about those other dragons?

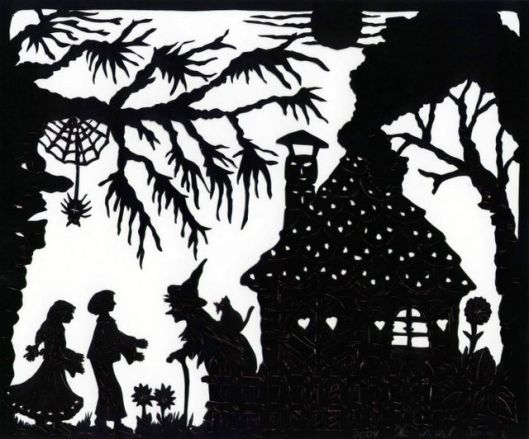

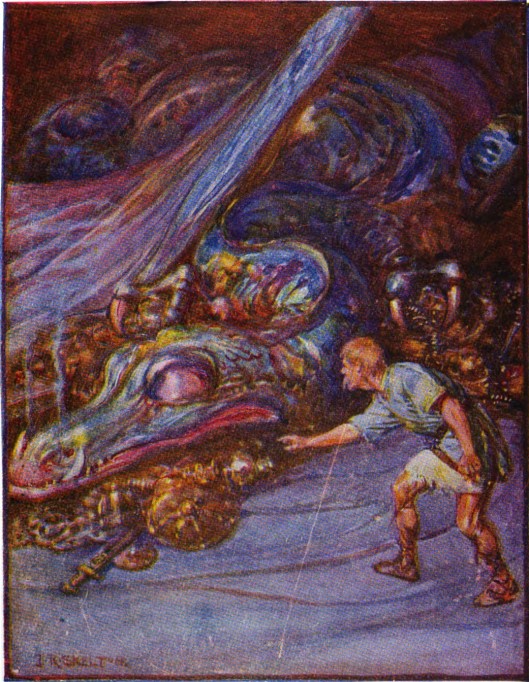

First, we thought of Kenneth Grahame’s Dream Days (1898),

a collection of short stories, the next-to-last of which is “The Reluctant Dragon”.

This is the story of a beast the very opposite of Smaug—no hoard, no suspicion, no flaming violence, and, in fact, a poetry lover. This story was then converted into a Disney cartoon of 1941.

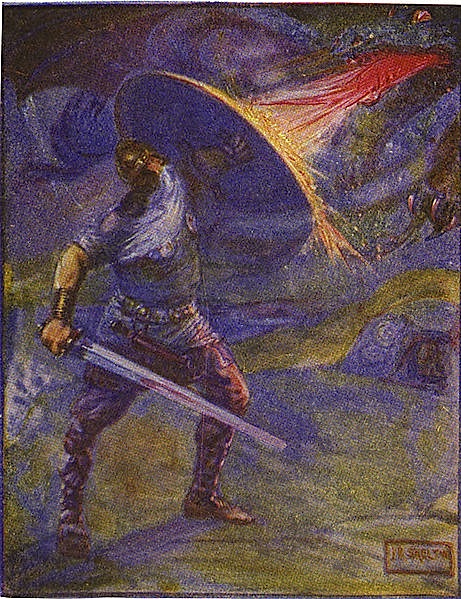

Needless to say, although the core of the plot is the same, what makes the Grahame distinctive is the language. All of the major characters: the dragon, the little boy who finds him, and St. George, who is brought in as a dragon-slayer, are thoughtful and articulate late Victorians who would rather discuss literature than do battle—a far cry not only from Beowulf’s encounter, but also from every other earlier depiction we could think of.

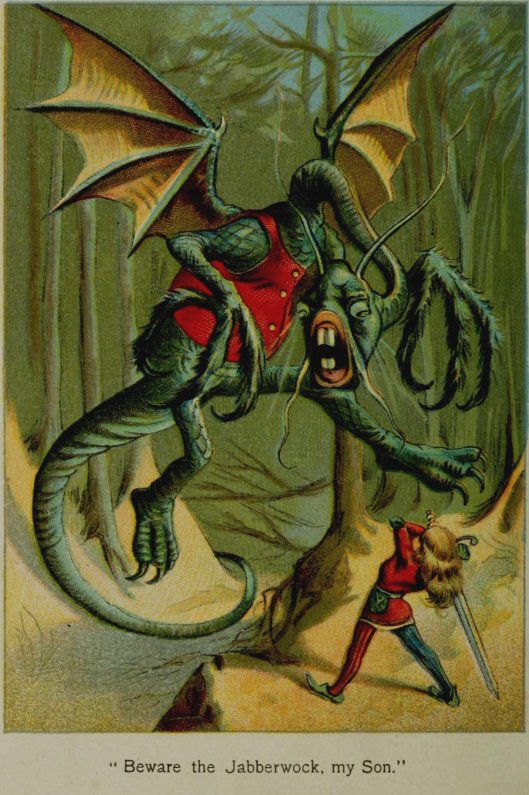

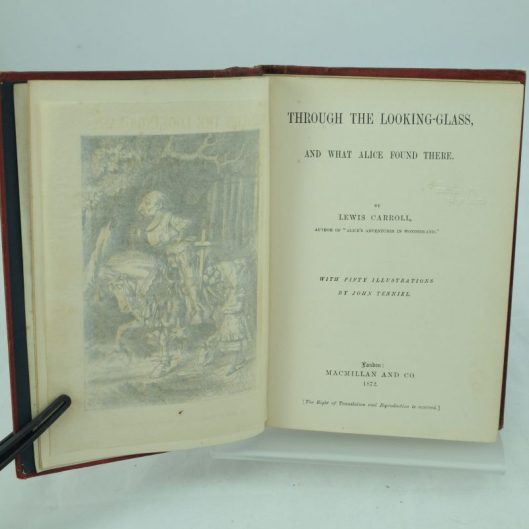

The sword in this last one looks like it actually belongs in the hands of the jabberwock-slayer

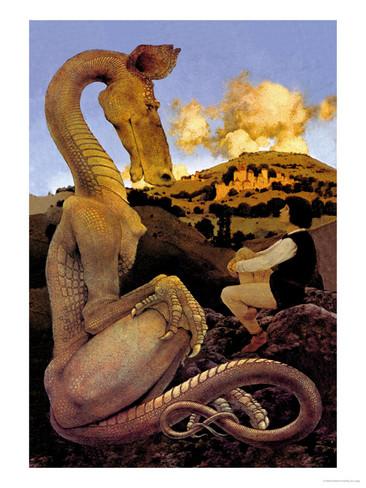

in Lewis Carroll’s Through the Looking-Glass (1872).

Here’s a LINK to Dream Days so that you can enjoy the story for yourselves.

Nearly sixty years later, the comic verse writer, Ogden Nash,

produced not a literary dragon, but a timid one in “Custard the Dragon” (1959).

This is a poem in 15 stanzas and is a story about Belinda and her pets, including a dragon, who is taunted by the other pets as being less than brave. To underline this, the last line in a number of stanzas is a variation upon the first version of the line, “But Custard cried for a nice safe cage”. (Here’s a LINK to the poem.)

The surprise is that, when a pirate climbs in through the window (this happens all the time here—possibly they escape from dreams?), Custard promptly eats him—and the cries of “Coward!” disappear immediately.

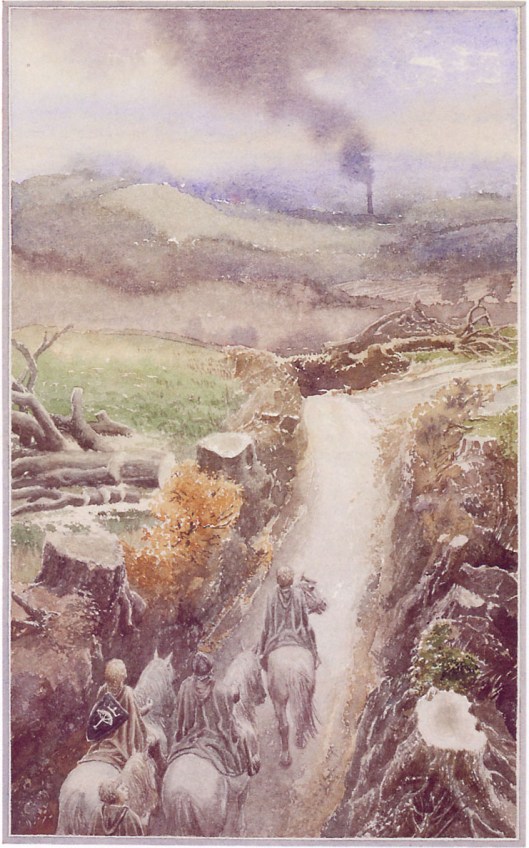

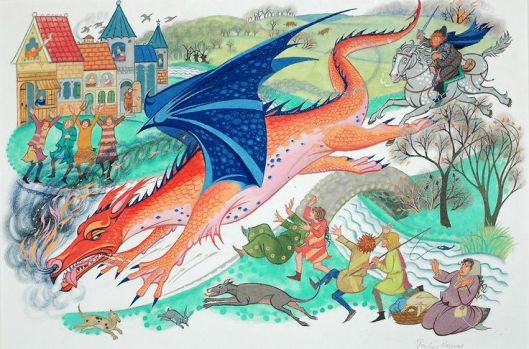

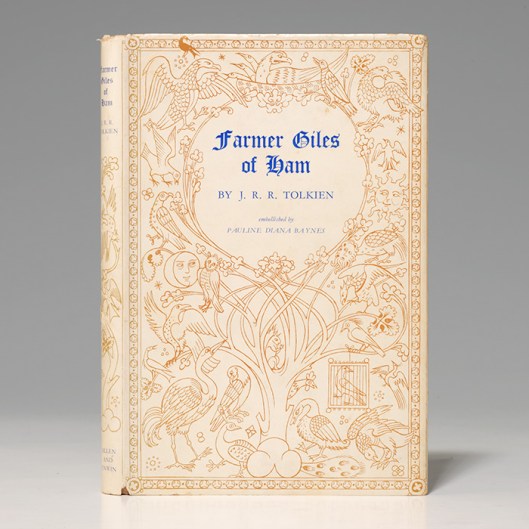

In contrast to the unnamed dragon in “The Reluctant Dragon” and in “Custard the Dragon”, our next dragon is a talker—like Smaug, but also like Smaug, potentially malevolent. This is Chrysophylax in JRRT’s 1937/1949 Farmer Giles of Ham. (JRRT is having a quiet joke here—“Chrysophylax” is Ancient Greek for “Goldguard”.)

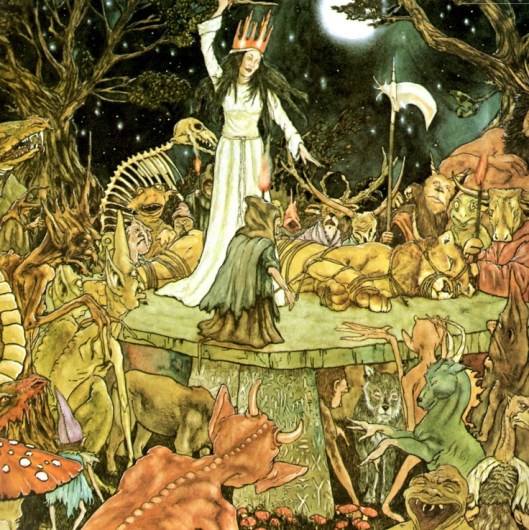

The artwork is by Pauline Baynes (1922-2008).

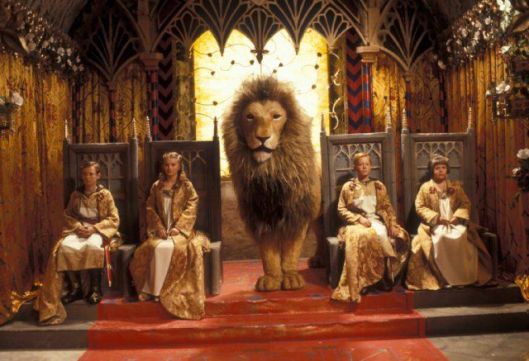

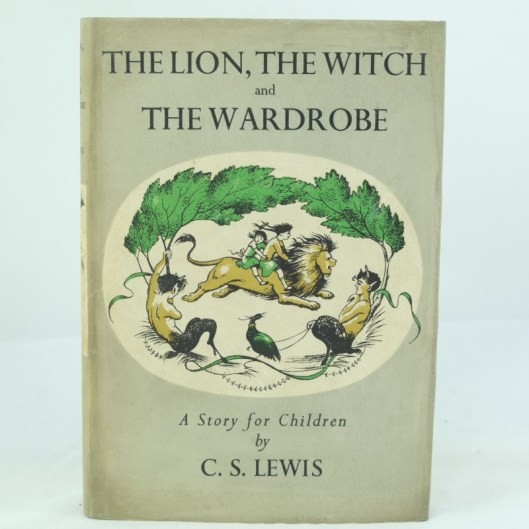

If, like us, you’ve loved the Narnia books, then you know her as their original illustrator.

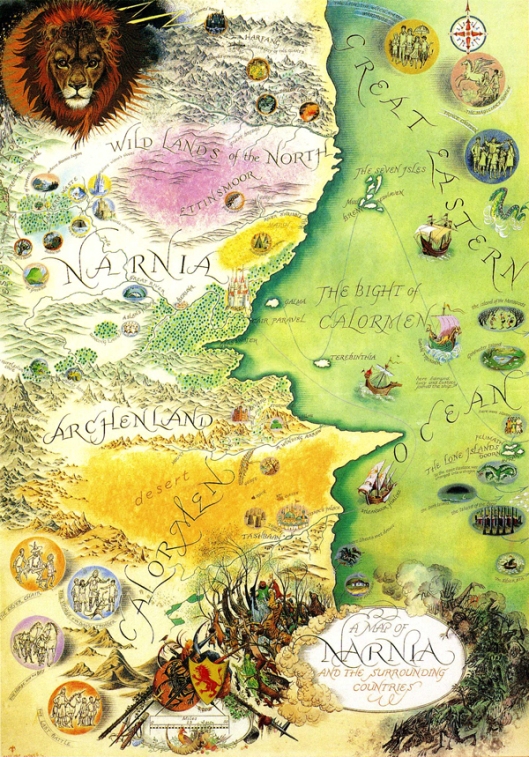

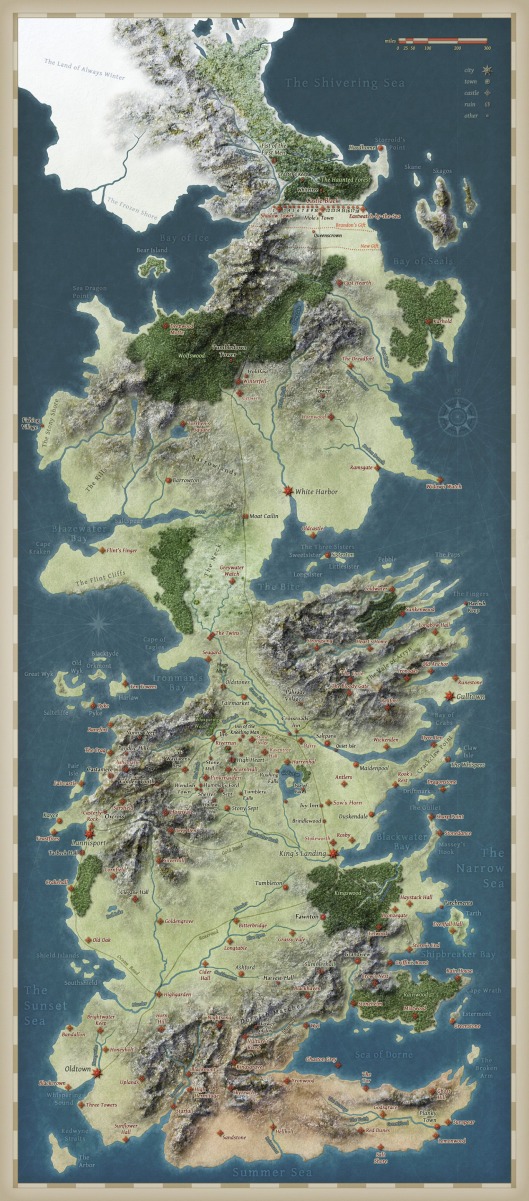

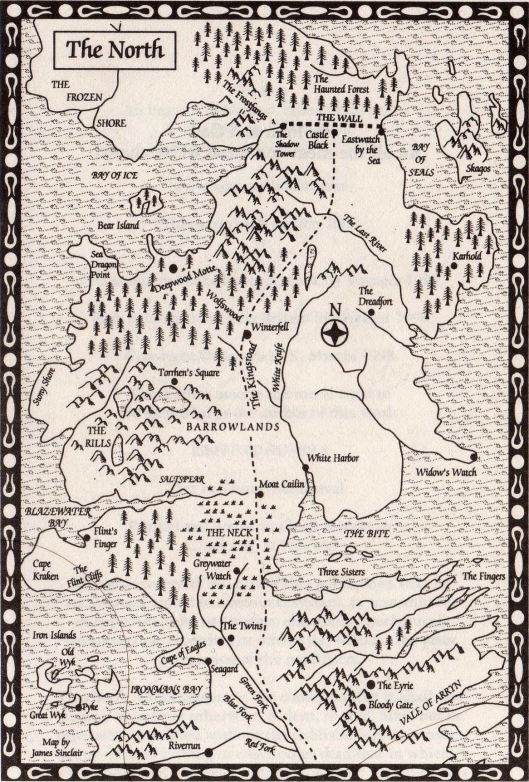

She was also the artist for an early Middle-earth map.

Her 2008 obituary in The Daily Telegraph tells of how they came to work together:

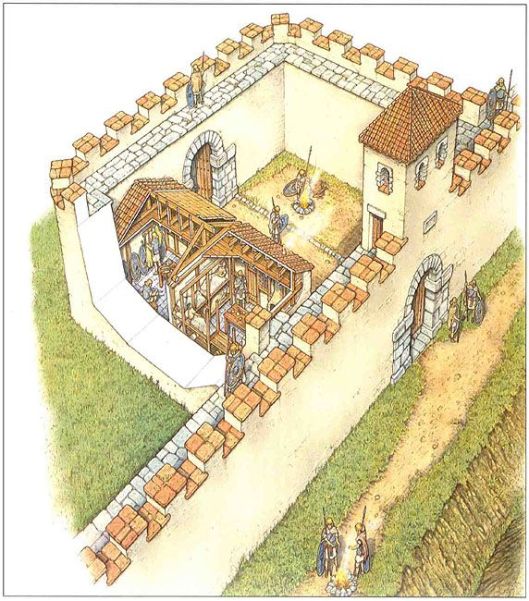

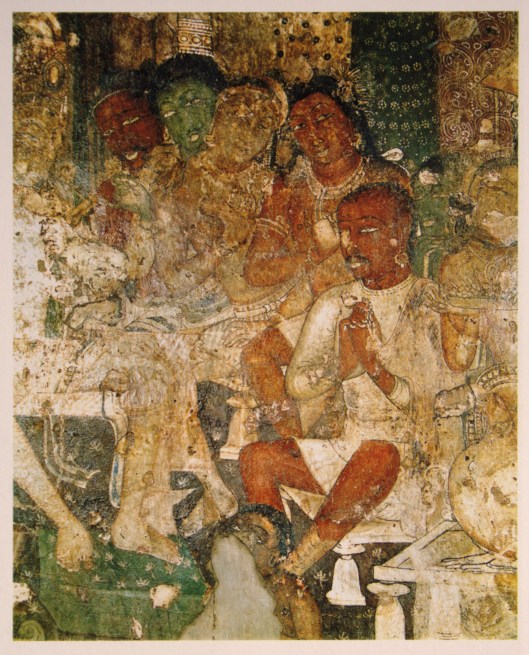

“In 1948 Tolkien was visiting his publishers, George Allen & Unwin, to discuss some disappointing artwork that they had commissioned for his novella Farmer Giles of Ham, when he spotted, lying on a desk, some witty reinterpretations of medieval marginalia from the Luttrell Psalter that greatly appealed to him. These, it turned out, had been sent to the publishers “on spec”by the then unknown Pauline Baynes.” (The Daily Telegraph, 8 August, 2008)

JRRT was then so impressed with her work that it appeared both in other later publications and his recommendation led to her being engaged by CS Lewis’ publisher for the Narnia books, as well. (And here’s a LINK to that obituary, which has more on Tolkien and Baynes, as well as Lewis.)

And the Baynes connection leads us to one further dragon, that in Rumer Godden’s (1902-1998) 1981 The Dragon of Og, for which Baynes provided the cover art.

It’s not our practice to discuss work we haven’t read, but we’ve just discovered this novel and have already put it on our spring reading list. The little we know about it comes from a blurb or two, but it looks promising: this is more of the reluctant dragon, but one who is in danger of being provoked by a new local lord until his wife steps in and cleverly changes the situation.

Before we close, however, we want to look back for a second at the Tolkien/Baynes connection and add two further things. First off, here’s the first page of JRRT’s graceful letter of thanks and praise to Baynes for her work in illustrating Farmer Giles.

Second, as the Telegraph obituary says, Tolkien was impressed with her versions of the marginalia from the Luttrell Psalter, which is high on our list of favorite medieval manuscripts.

In our next, we want to spend some time looking at that work, thinking about marginalia, and not only there, but also in the work of another favorite illustrator, Arthur Rackham (1867-1939).

Till then, thanks, as always, for reading.

MTCIDC

CD