Tags

24Hr Trench, Andrew Robertshaw, architecture, Birmingham, Brandywine, crop rotation, Diamond Jubilee, dugouts, Dunedain, feudal system, German lawn chairs, Hornblotton, Inns, Laura Ingalls Wilder, Lavenham, manor, Marish, Medieval, Queen Elizabeth II, Queen Victoria, Sarehole, Sarehole's mill, Somerset, Suffolk, The Hobbit, The Lord of the Rings, The Shire, Tolkien, village, Western Front, WWI Trenches

Welcome, dear readers, as always.

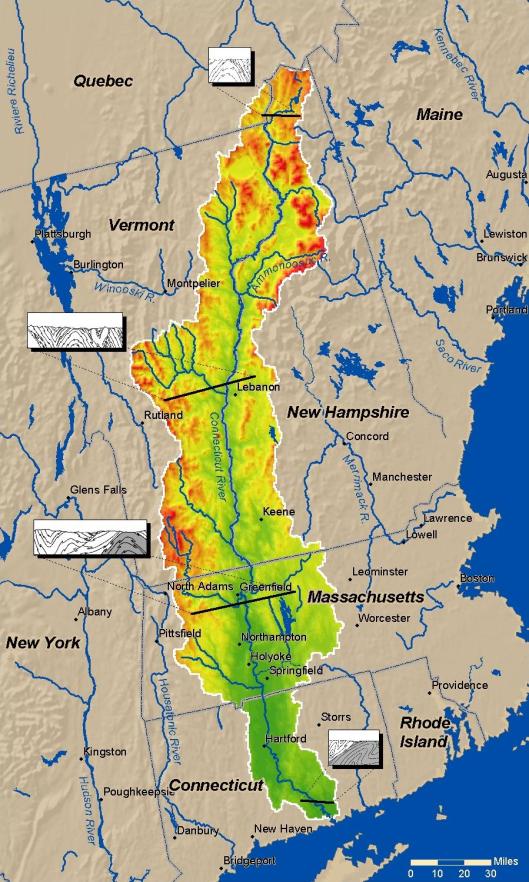

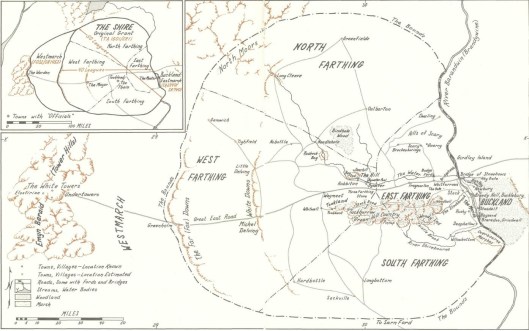

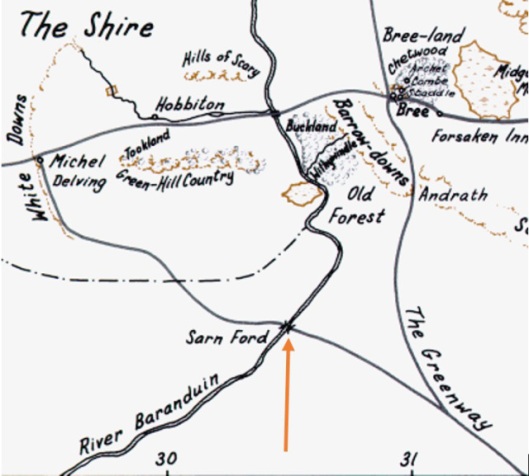

In this post, we’re continuing our series on the Shire. So far, we’ve looked at its government and organization (1), its economy (2), and its geography (3a). Now we want to look at Shire architecture.

Our initial inspiration for this was from a line in a letter from JRRT to Allen & Unwin, 12/12/55. Speaking of the Shire, he says: “It is in fact more or less a Warwickshire village about the period of the Diamond Jubilee… (Letters, 230)

The “Diamond Jubilee” was the 60th anniversary of the reign of Queen Victoria (she came to the throne in 1837–Queen Elizabeth II celebrated her Diamond Jubilee just five years ago).

The Jubilee was a huge celebration, bringing in people from all over Britain’s empire, who converged on London in the summer of 1897.

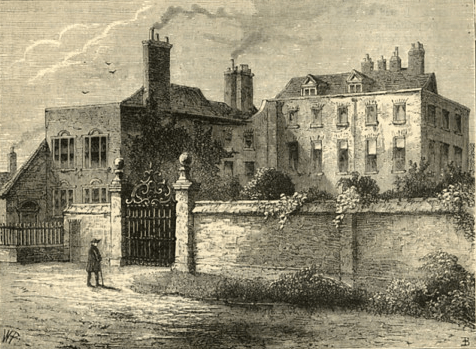

JRRT was born in 1892 and had been brought to England in 1895, for a visit which became permanent when his father died back in South Africa. He and his brother

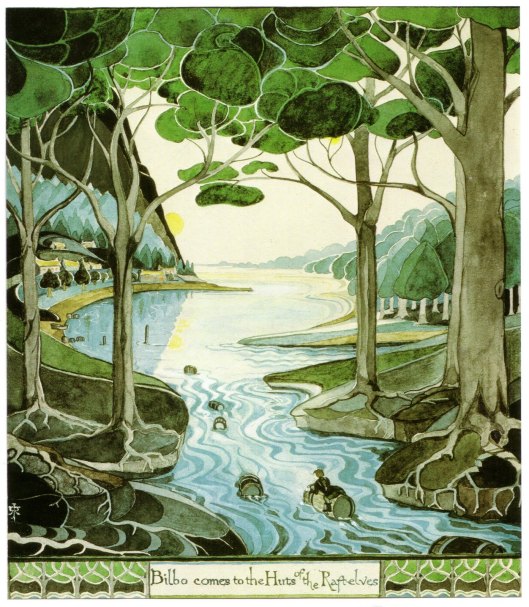

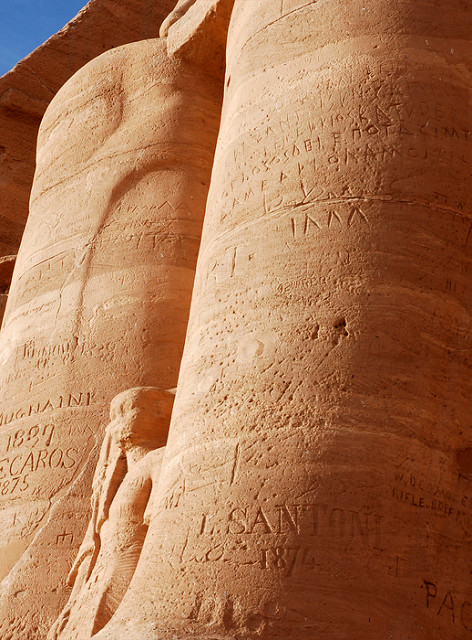

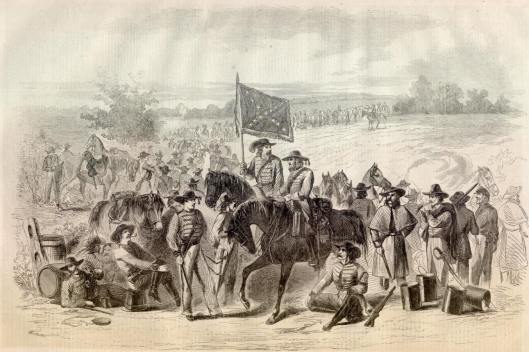

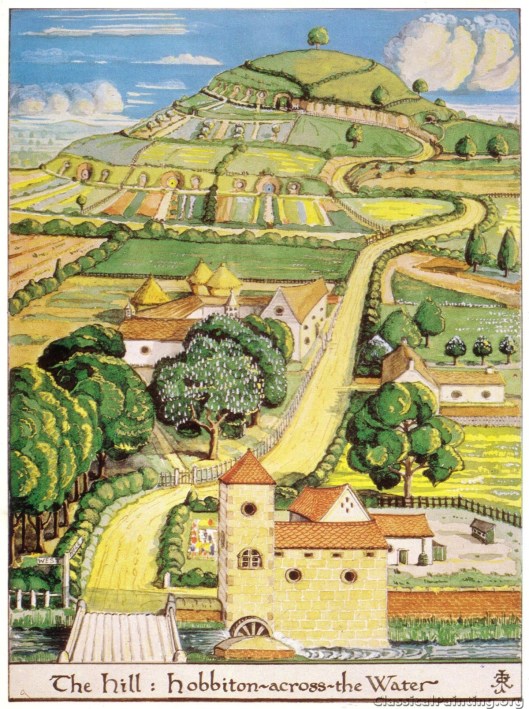

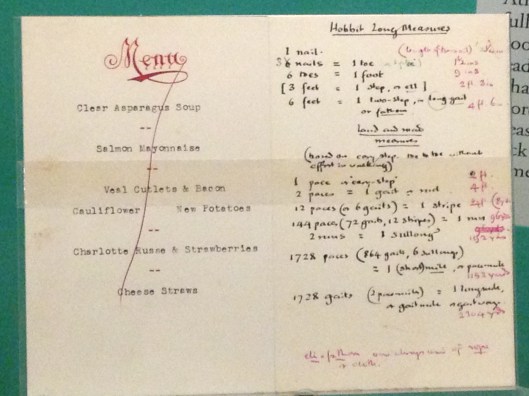

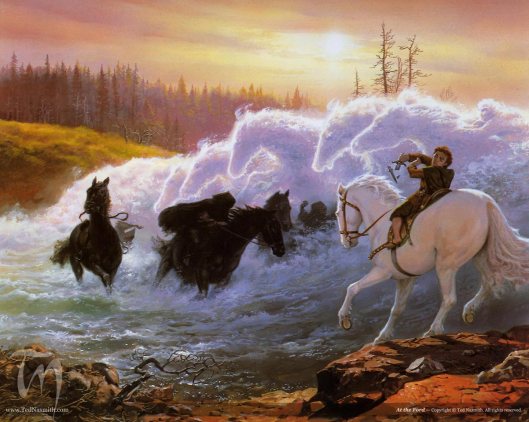

lived with their mother for a time in the village of Sarehole, just south of the huge industrial city of Birmingham. Sarehole’s mill

still stands. It has been said that this mill is the model for the one by The Water in The Hobbit, as drawn by JRRT.

Thus, when we think about Shire architecture, we can have a double picture:

- bits of description in JRRT’s works

- actual late Victorian rural villages of the sort in which Tolkien spent part of his childhood

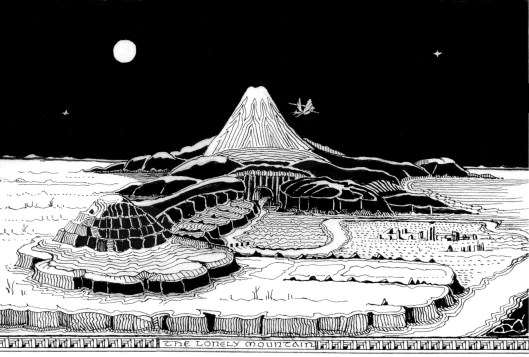

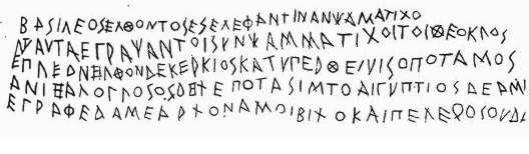

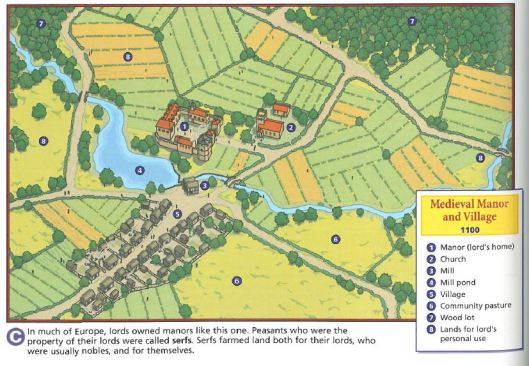

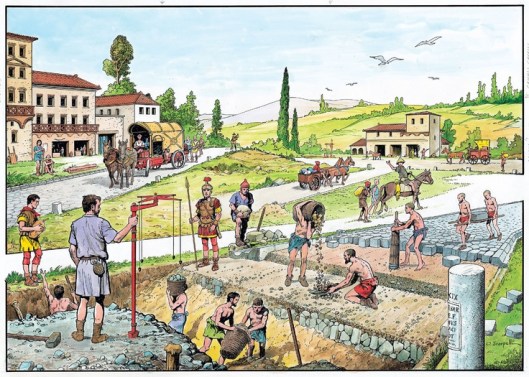

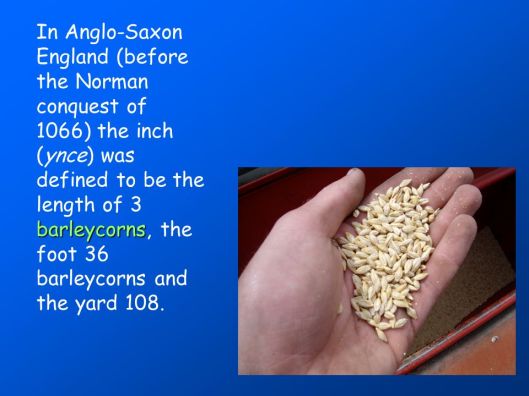

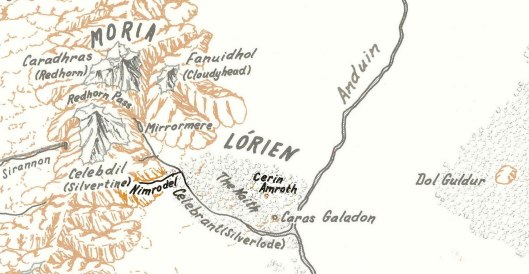

If we begin with historical villages, there isn’t anything to see in the actual Sarehole, except for the mill, which, though built upon the site of a mill which can be dated to 1542, is a building from 1771, just before the industrial revolution, an event with which Tolkien certainly had problems. If we look at other such villages, however, we can get a general picture. Basing our image upon a schematic medieval village plan, we find a double line of houses strung out along a single road.

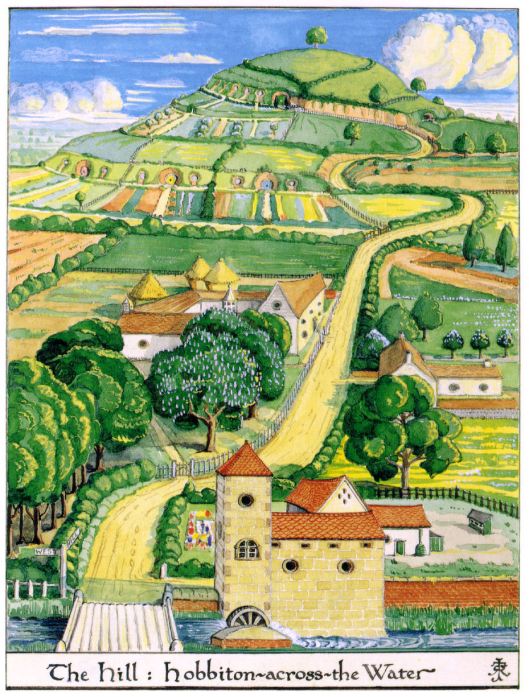

Spreading back from the houses are the fields, as villages in this world were self-sustaining. You can see these in JRRT’s illustration of the mill and the Hill. You’ll notice that these are in strips. In the feudal world, they illustrated both the use of crop rotation (different plants in different fields, with some fields allowed to rest), plus fields of the lord of the manor, which the tenants were obliged to tend. In Tolkien’s Shire, as there is no feudal system, we presume the stripping is for rotation.

Missing, however, from Hobbiton, would be two features you can see in the medieval illustration: a manor house and a church.

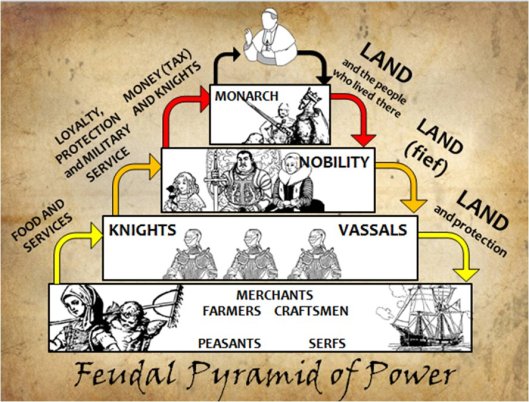

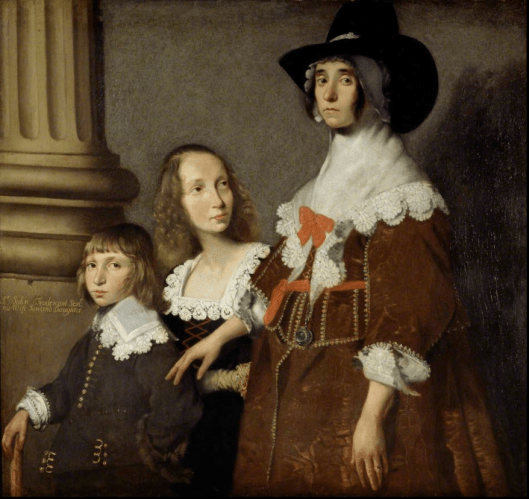

In the feudalism mentioned above, this ideal village is part of the social/governmental system in which it is attached to the smallest unit of that system, the manor.

As the chart explains, in the early medieval world, land was power and kings used their claim to control their lands (supposedly given to them by God) as a way to control the state in general. They deeded certain sections of land to their nobles, in return for taxes and military service. Those nobles, in turn, deeded out land to lesser nobles, all the way down to individual knights, who might hold no more than one parcel, or manor, with its house, church, and village of freemen (literally, free men, who could own land but paid taxes to the lord for it), peasants (who were also free, but held no land), and serfs (who were landless as well as being the property of the local lord).

Although Tolkien once described the Shire as “granted as a fief” (Letters, 158) and “half republic half aristocracy” (Letters, 241), it is not a feudal property and therefore lacks those marks of that system, those manor houses.

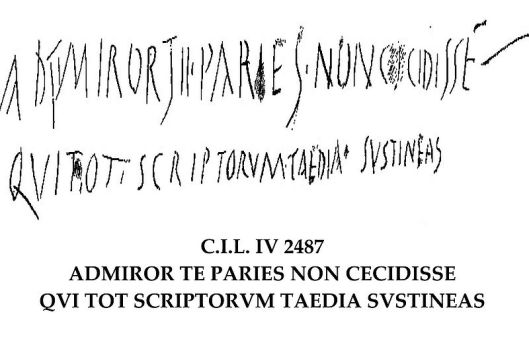

As well, it is also missing churches, or, for that matter, any form of religious shrine. A real English medieval village, depending on its size and wealth, could have had a very modest building, such as this at Hornblotton, in Somerset.

Or, if your village had become a prosperous town, like Lavenham, in Suffolk, you could even have a mini-cathedral. (Lavenham’s money had come from the international trade in woolen cloth.)

Although Tolkien insisted that there was a monotheistic underlay to Middle-earth in the Third Age, he also says of the folk of the Shire: “I do not think Hobbits practiced any form of worship or prayer (unless through exceptional contact with Elves).” (Letters, 193)

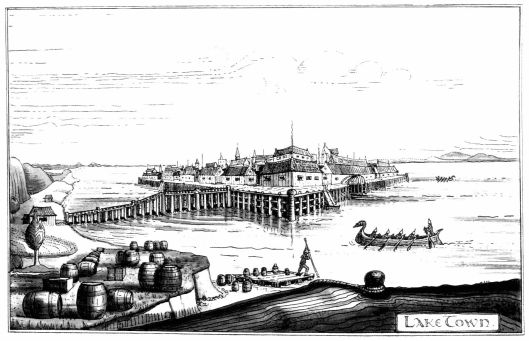

Without manors and churches, the Shire consists of private dwellings and inns. Inns seem to be like their parallels in our medieval world.

And, of course, there are the inns of the Shire and the Prancing Pony in Bree.

Private houses, including farms, however, fall into two categories: traditional hobbit (that is, built into hillsides) and what we might call outside-influence houses. As Tolkien says in the Prologue to The Lord of the Rings:

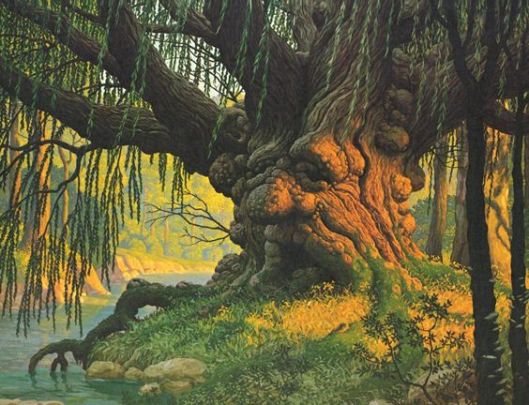

“All Hobbits had originally lived in holes in the ground, or so they believed…Actually in the Shire of Bilbo’s days it was, as a rule, only the richest and the poorest Hobbits that maintained the old custom. The poorest went on living in burrows of the most primitive kind…while the well-to-do still constructed more luxurious versions of the simple diggings of old…in the hilly regions and the older villages, such as Hobbiton and Tuckborough, or in the chief township of the Shire, Michel Delving on the White Downs, there were now many houses of wood, brick, or stone…Hobbits had long accustomed to build sheds and workshops…

The habit of building farmhouses and barns was said to have begun among the inhabitants of the Marish down by the Brandywine.

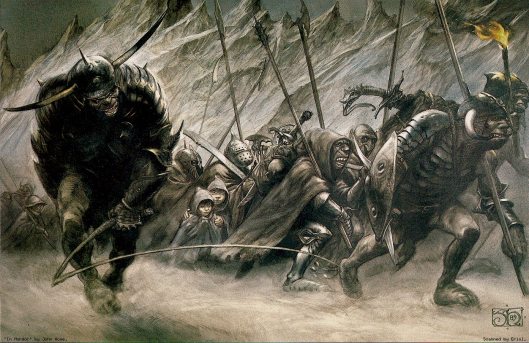

It is probable that the craft of building, as many other crafts beside, was derived from the Dunedain. But the Hobbits may have learned it direct from the Elves… “

Our Tolkien illustration of The Hill

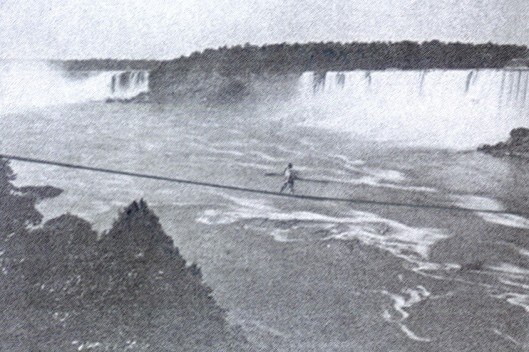

shows us both styles. In the background, burrows; in the foreground, outside-influence houses. The traditional style reminds us of something from US western history: the use of “dugouts” as (at least temporary) dwellings as settlers moved west across the plains.

As fans of the Laura Ingalls Wilder books will remember, her family lived in one of these along the banks of Plum Creek in the 1870s.

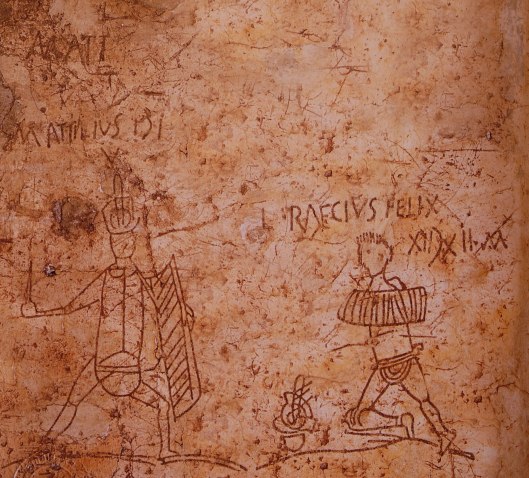

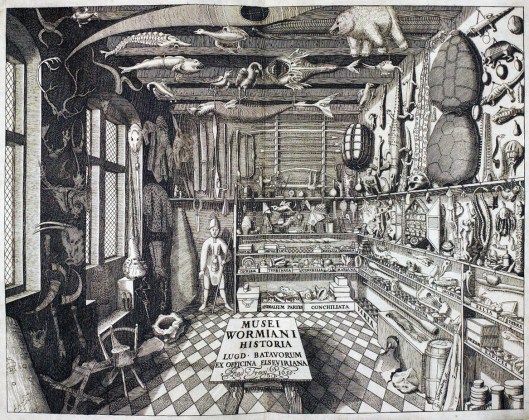

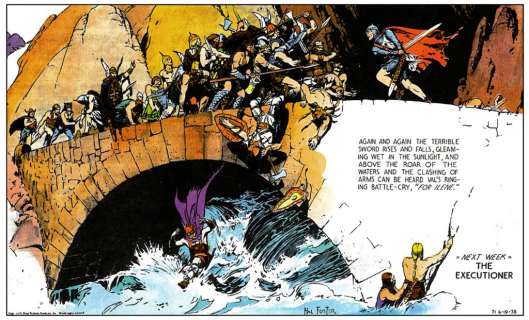

On a more sinister note, we’ve always wondered whether JRRT’s inspiration for hobbit holes may have come from his time on the Western Front, where, from late 1914, soldiers had burrowed into the earth to protect themselves from enemy attack and from the increasingly inclement weather. The shelters could be simply cutouts in the earth

or very elaborate cottages. The Germans were especially admired for their creativity in building the more elaborate ones.

We can’t mention the Great War and trenches without also mentioning the brilliant Andrew Robertshaw, the English military historian, who actually reconstructed sixty feet of a trench line in his backyard.

He shares his experience in doing this in his book, 24Hr Trench.

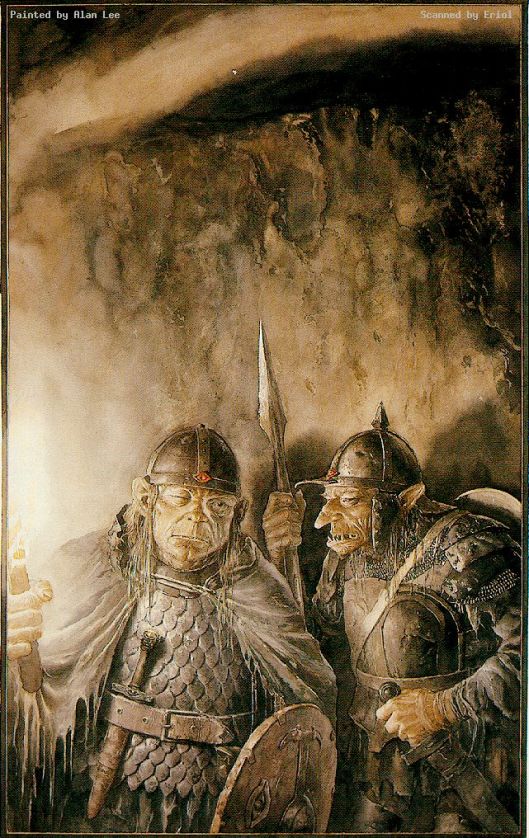

Continuing our medieval parallel, we imagine the outside-influence houses to look something like these:

And, for outbuildings, there are a few surviving medieval barns, like this one:

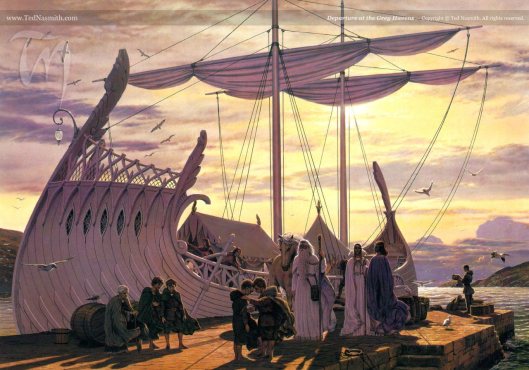

whose roofs are often held up by the most beautiful woodwork, always reminding us of cathedrals, on the one hand, and sailing ships on the other.

Imagine that this is what Farmer Cotton’s farm might have looked like.

And, with this image, we conclude this posting. In our next, we’re going to move to the edge of the Shire, to discuss marches—geographical ones, that is.

Thanks, as ever, for reading!

MTCIDC

CD

)

)