Tags

Anglo-Frisian Runes, Balin, Bryggen, divination, Fireworks, Futhark, Futhorc, Gandalf, Harys Dalvi, Kylver Stone, Moria, Robwords, runes, Tacitus, The Lord of the Rings, Thror's Map, Tolkien, Vimose comb

Welcome, as ever, dear readers.

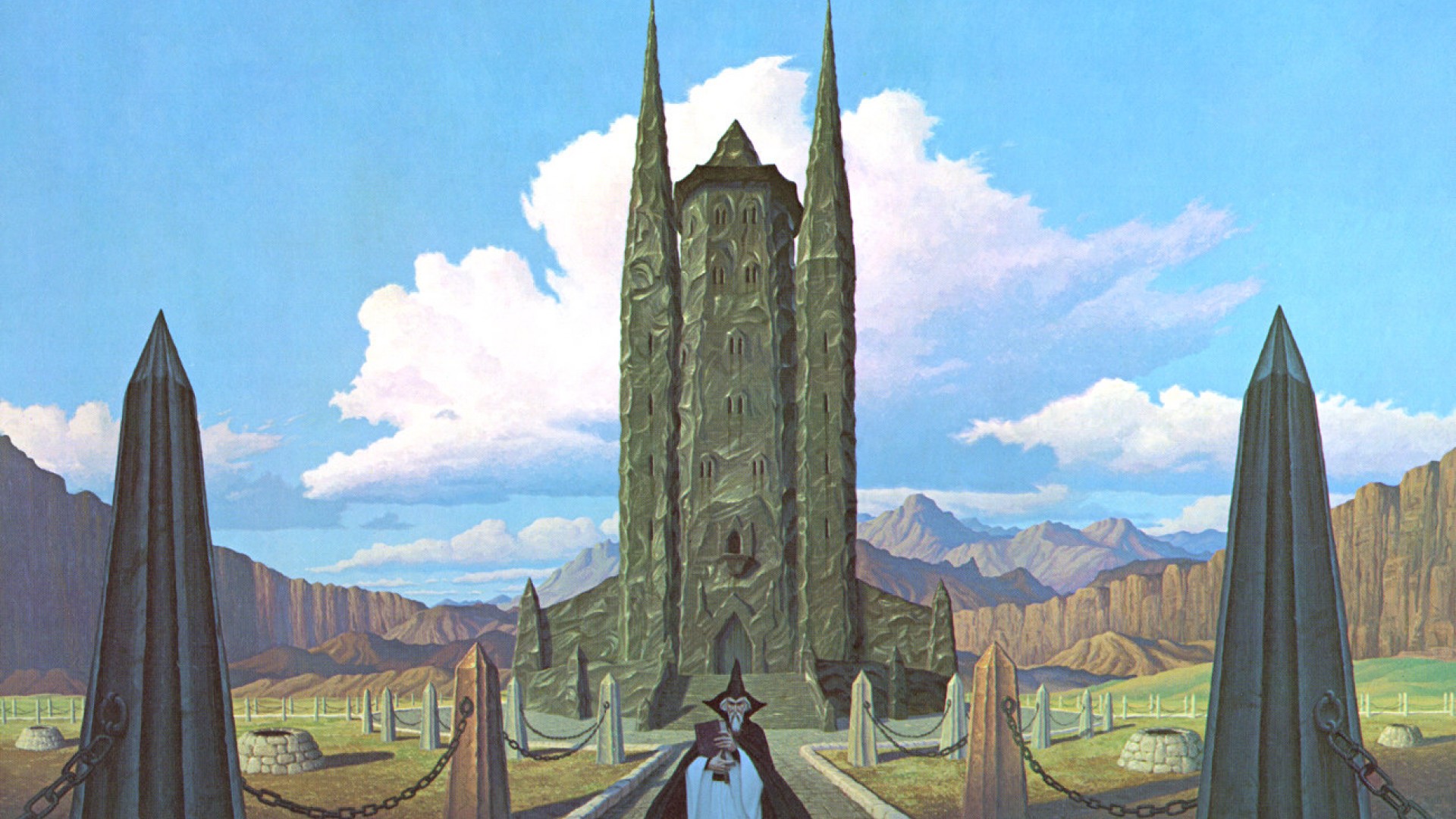

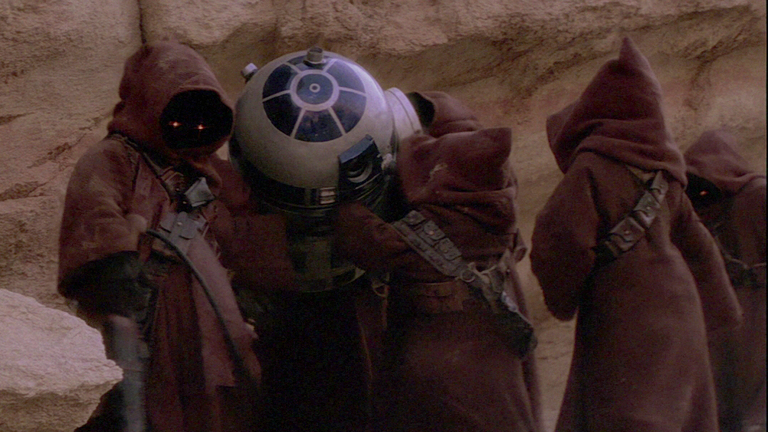

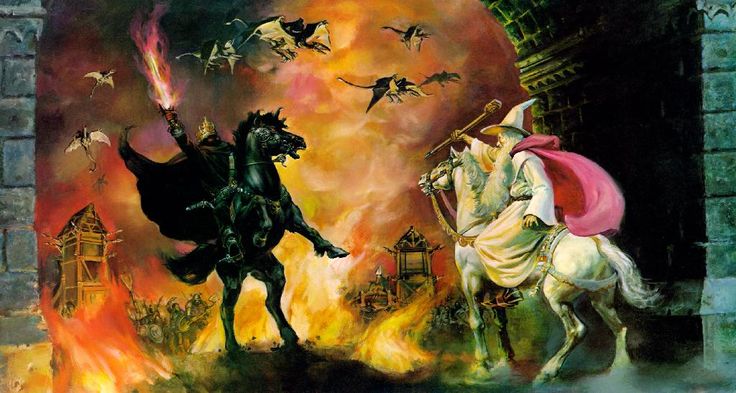

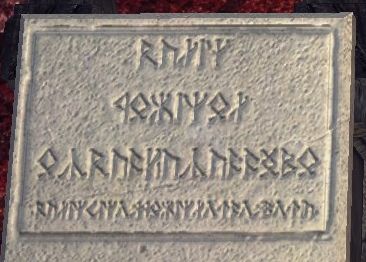

It is a grim moment, in The Lord of the Rings when the company, making its way through the complexity of Moria in near-darkness, save for Gandalf’s staff, reaches this—

“Their feet disturbed a deep dust upon the floor, and stumbled among things lying in the doorway whose shapes they could not at first make out. The chamber was lit by a wide shaft high in the further eastern wall; it slanted upwards and, far above, a small square patch of blue sky could be seen. The light of the shaft fell directly on a table in the middle of the room: a single oblong block, about two feet high, upon which was laid a great slab of white stone.

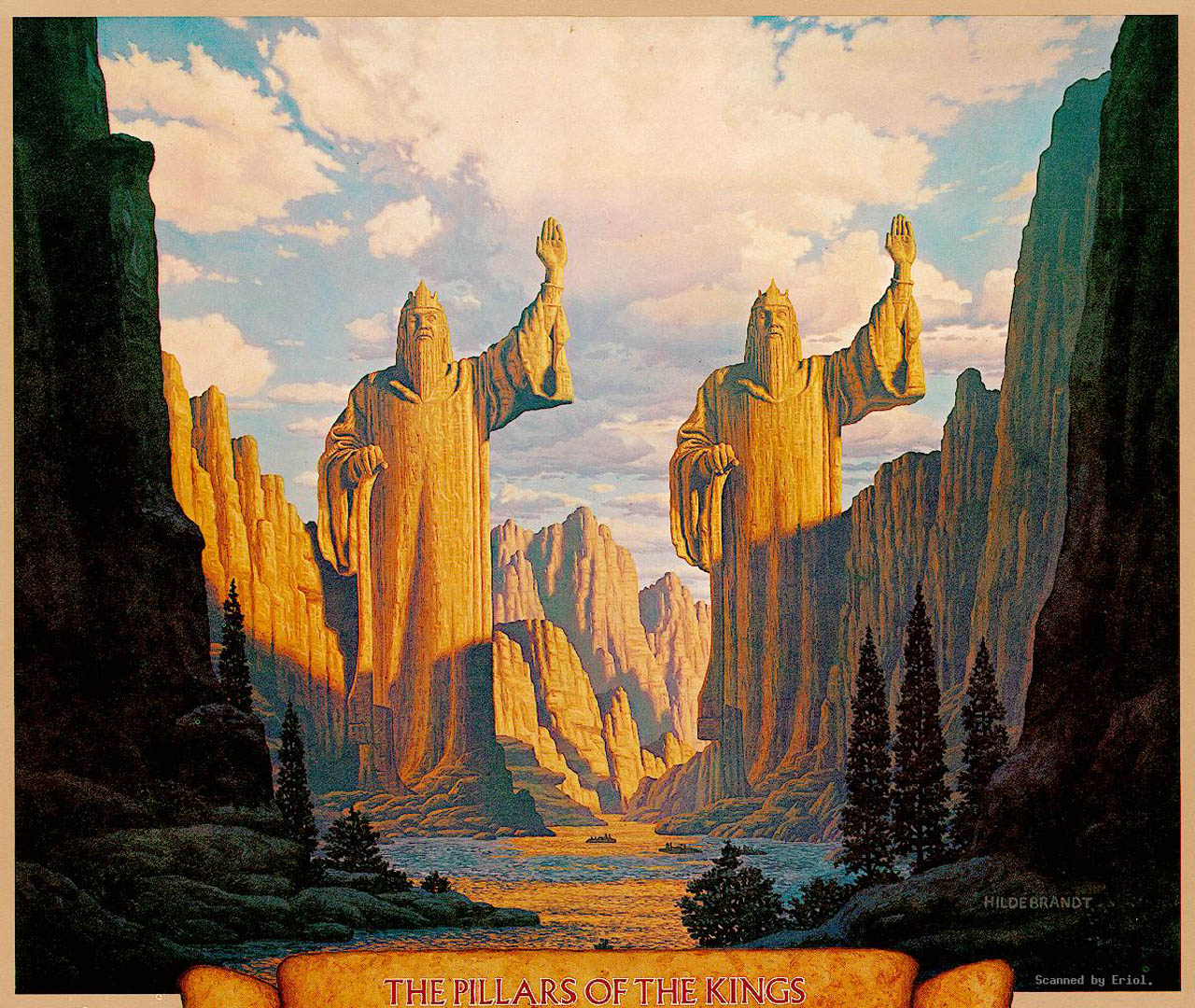

(the Hildebrandts)

‘It looks like a tomb,’ muttered Frodo, and bent forwards with a curious sense of foreboding, to look more closely at it. Gandalf came quickly to his side. On the slab runes were deeply graven:

‘These are Daeron’s Runes, such as were used of old in Moria,’ said Gandalf. ‘Here it is written in the tongues of Men and Dwarves:

BALIN SON OF FUNDIN

LORD OF MORIA ‘.” (The Lord of the Rings, Book Two, Chapter 4, “A Journey in the Dark”)

Even if you’re not an expert in early western writing systems, you’ve probably encountered runes before. They appear to be a Germanic invention, with their first known outside mention thought to be in P. Cornelius Tacitus’ (c.56-c.120 AD) essay on some northern tribes, Germania, where this passage is cited.

“[10] Auspicia sortesque ut qui maxime observant: sortium consuetudo simplex. Virgam frugiferae arbori decisam in surculos amputant eosque notis quibusdam discretos super candidam vestem temere ac fortuito spargunt. Mox, si publice consultetur, sacerdos civitatis, sin privatim, ipse pater familiae, precatus deos caelumque suspiciens ter singulos tollit, sublatos secundum impressam ante notam interpretatur.”

“[the Germans] pay very close attention to auspices and lot-drawing: the practice of lot-drawing is simple. They split a branch cut from a fruit tree into splinters and scatter those, marked out with certain signs, on a white robe casually and randomly. Then a priest of the settlement, if it may be the public consulting of an oracle, but if private, the father of a family himself, having prayed to the gods and raising his eyes to the sky, draws three [splinters] one at a time [and] interprets those drawn according to the mark stamped upon [them] previously.”

(Tactius, Germania, Section 10—my translation. If you’d like to read the whole text, here’s a useful Victorian translation: https://archive.org/details/tacitusagricolag00taciiala/page/62/mode/2up )

We don’t know where Tacitus got his information from, but he lived at about the same time as one of the earliest currently-known runic inscriptions, the “Vimose comb”, dated to about 160AD,

(There seem to be two guesses at to what the inscription says—transliterated, it appears to read “harja”, meaning either the obvious “comb” or the less obvious “warrior”. For more on this and other early rune-marked artifacts, see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vimose_inscriptions and https://en.natmus.dk/historical-knowledge/denmark/prehistoric-period-until-1050-ad/the-early-iron-age/the-weapon-deposit-from-vimose/the-offerings-in-vimose/ Until they sold out, you could even get a bone replica of the comb here: https://norseimports.com/products/vimose-comb )

so the notae, “marks”, he mentioned could, indeed, be early runes.

We’ve seen runes three times before in the book, each time related to Gandalf and the first letter of his name in runes–

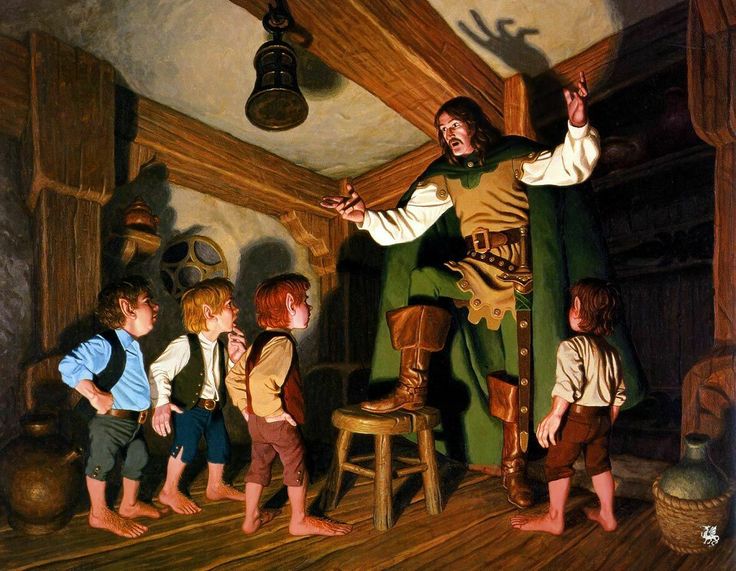

The first is a jolly appearance:

(Darrell K. Sweet, who died, unfortunately, in 2011, but you can see his archived website here: https://web.archive.org/web/20110131141507/http://www.sweetartwork.com/DKSmainPage.html and read a little more about this very talented illustrator here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Darrell_K._Sweet And I couldn’t resist adding this knowledgeable appreciation of his work: https://blackgate.com/2022/04/17/an-adventure-to-be-had-a-journey-through-the-art-of-darrell-k-sweet/ )

“At the end of the second week in September a cart came in through Bywater from the direction of Brandywine Bridge in broad daylight. An old man was driving it all alone…It had a cargo of fireworks…At Bilbo’s front door the old man began to unload: there were great bundles of fireworks of all sorts and shapes, each labeled with a large red G [runic letter] and the elf-rune [see the image above].” (The Fellowship of the Ring, Book One, Chapter 1, “A Long-Expected Party”)

The second is not, being Gandalf’s much-delayed letter to Frodo, still at the Prancing Pony in Bree, instead of being delivered 3 months before to the Shire, meant to alert Frodo to the possibility that he won’t meet them, with some consolation that Strider might appear. (The Fellowship of the Ring, Book One, Chapter 10, “Strider”)

(the Hildebrandts)

And the third is only guessed at as seeming to be a sign from Gandalf on Weathertop:

“ ‘The stroke on the left might be a G-rune with thin branches,’ said Strider. ‘It might be a sign left by Gandalf, though one cannot be sure…I should say…that they stood for G3, and were a sign that Gandalf was here on October the third: that is three days ago now. It would also show that he was in a hurry and danger was at hand, so he had no time or did not dare to write anything longer or plainer. If that is so, we must be wary.’ “ (The Fellowship of the Ring, Book One, Chapter 11, “A Knife in the Dark”)

(John Howe)

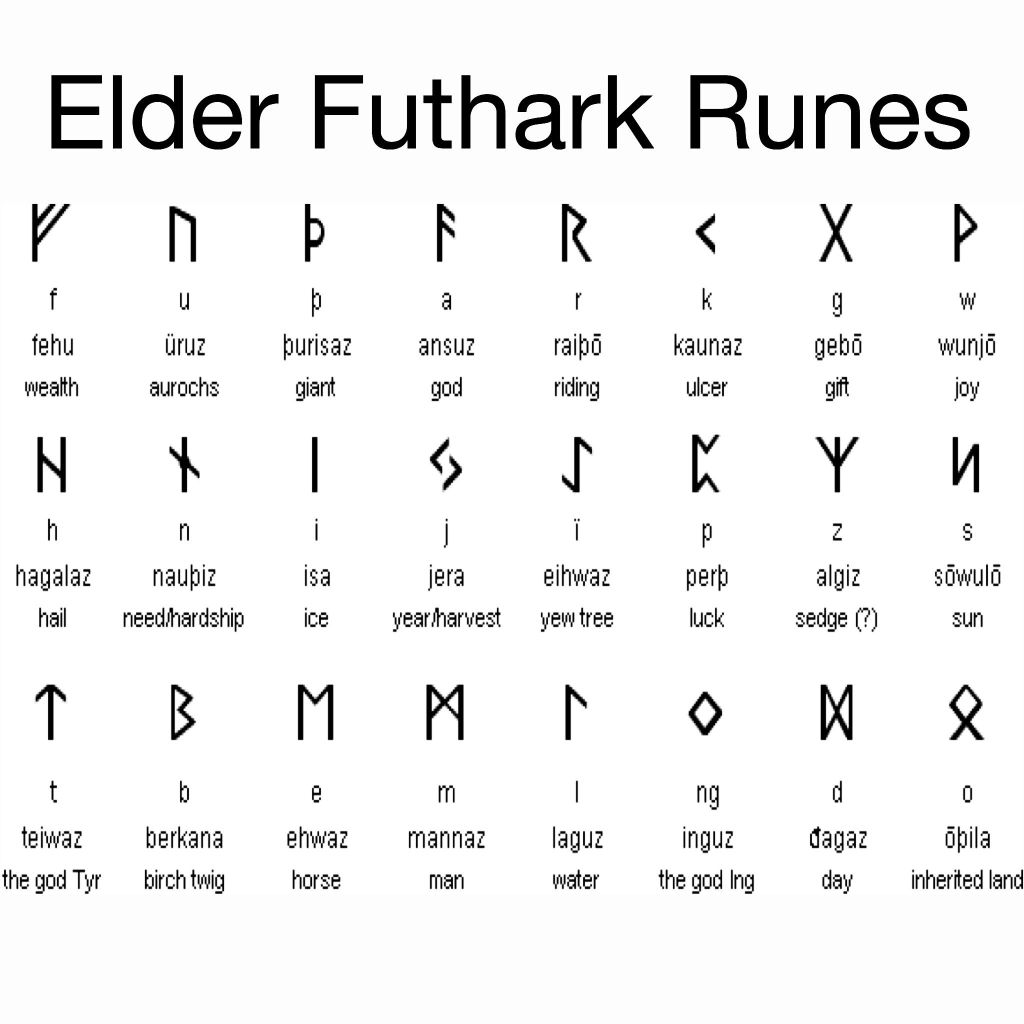

In our Middle-earth, there are several iterations of runes, with the melodious (modern) names of “Futhark”(Elder and Younger) and “Futhorc”, which get those names, as the word “alphabet” does, from putting together a collection of the first letters of the series in a standard order. Here’s the Elder Futhark—

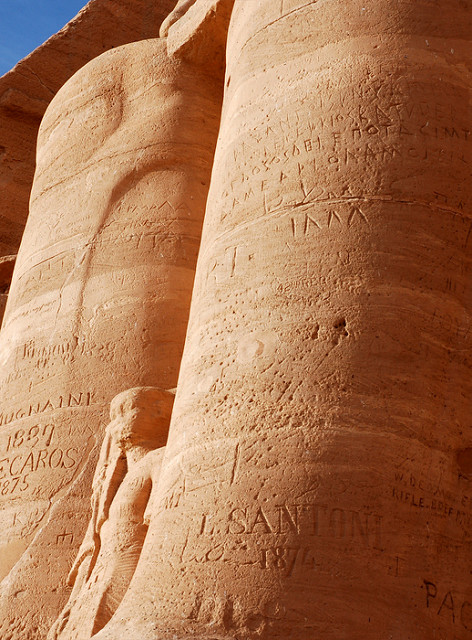

It’s easy to see why the letters might be shaped as they were, appearing to be relatively easy to inscribe on things with a knife. (Or a chisel for the stone inscriptions?)

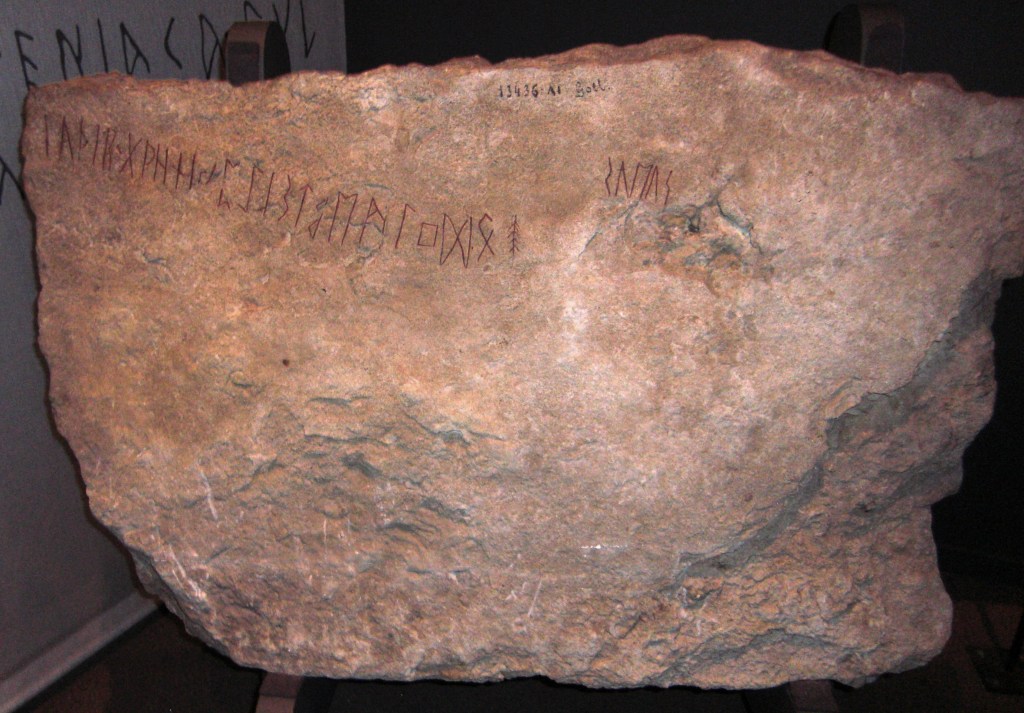

(a 12th-century AD inscription on wood from Bryggen in Norway—one of 670 inscriptions on wood or bone found at the site since 1955—for more see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bryggen_inscriptions and https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bryggen One of the many amazing things about this second piece is that it underlines just how sophisticated trade could be in northern Europe in the Middle Ages.)

(This is the Kylver Stone from Gotland, Sweden, c.400AD, which lists the Elder Futhark letters. For more, see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kylver_Stone and you can see from the translation of the runes where “Futhark” came from. )

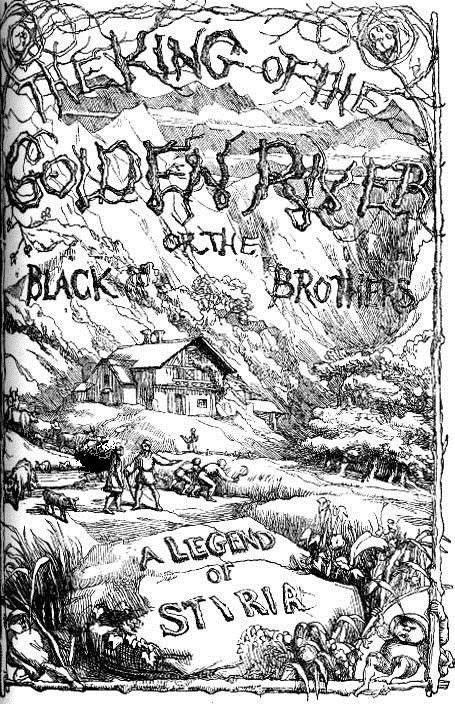

Tolkien’s own runes, as he tells us, are derived from what are sometimes called the “Anglo-Saxon” or “Anglo-Frisian” Futhorc:

“There is the matter of the Runes. Those used by Thorin and Co., for special purposes, were comprised of an alphabet of thirty-two letters (full list on application), similar to, but not identical, with the runes of Anglo-Saxon inscriptions.” (letter to the editor of The Observer, published there 20 February, 1938, Letters, 42)

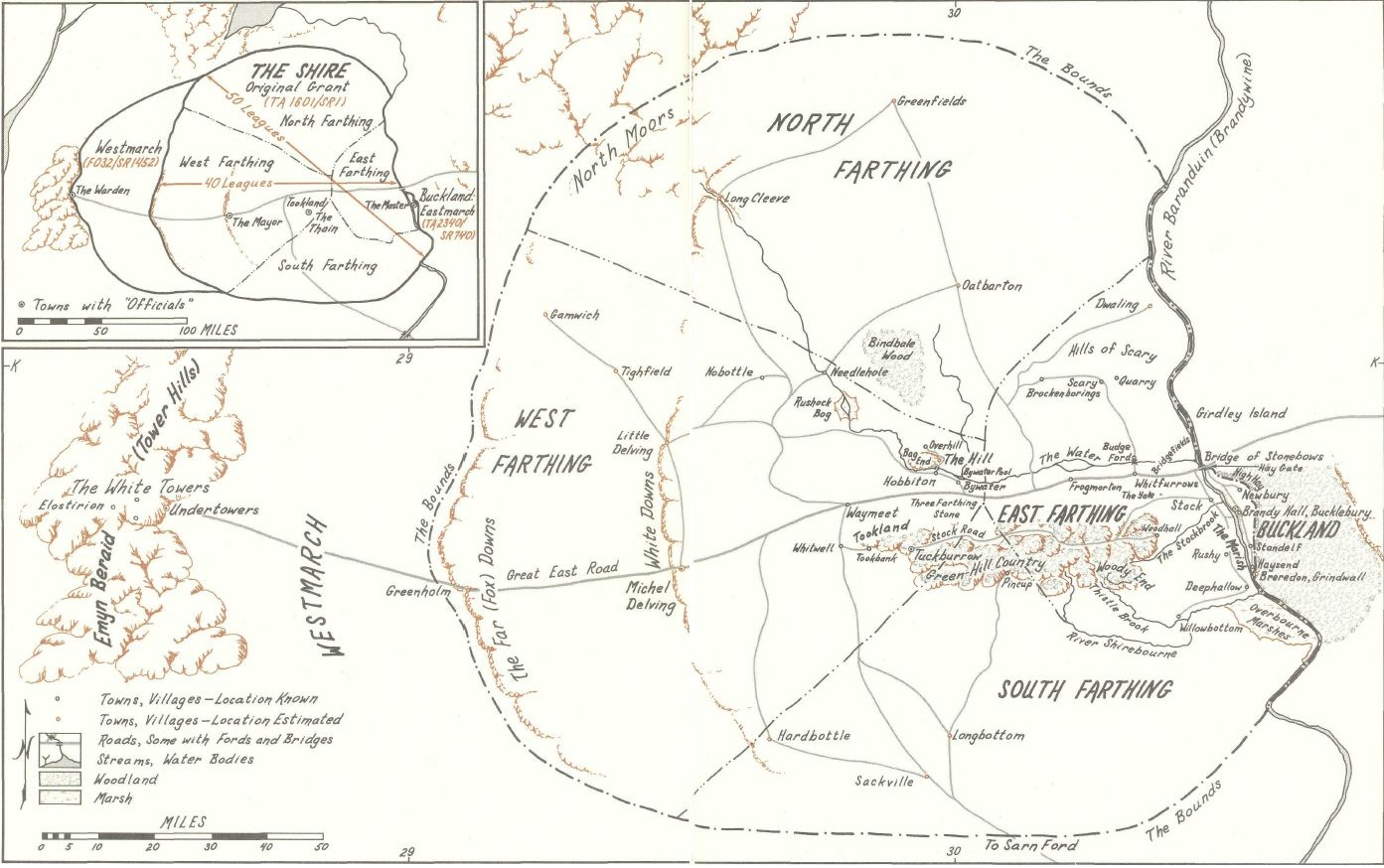

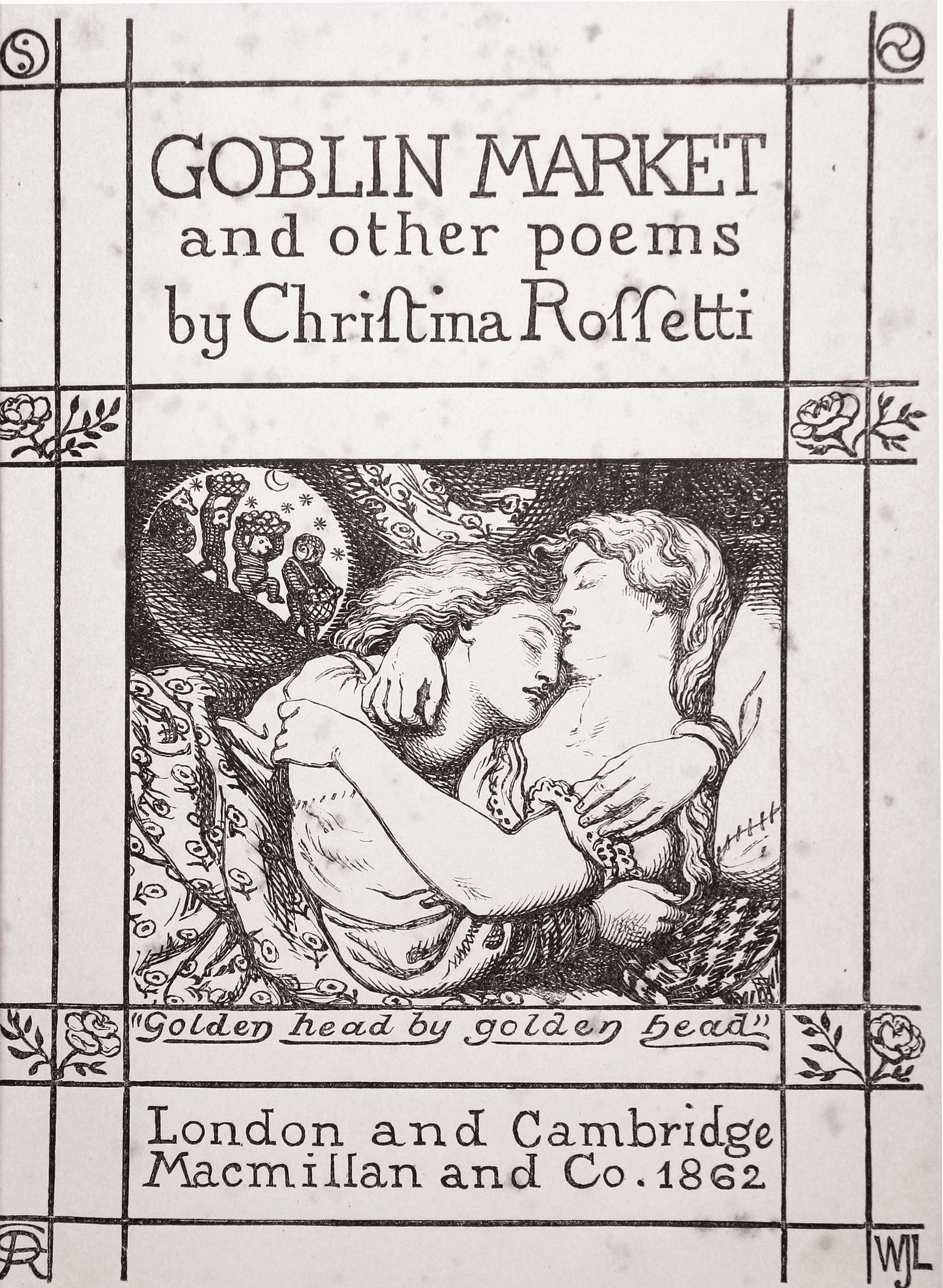

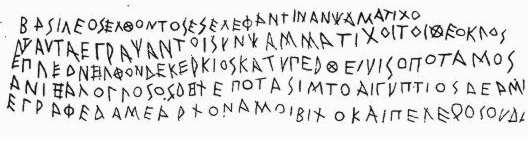

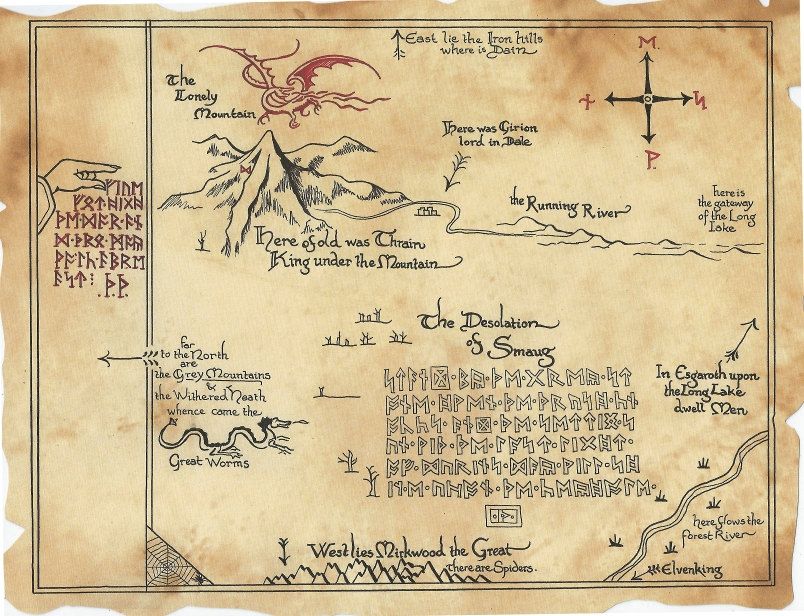

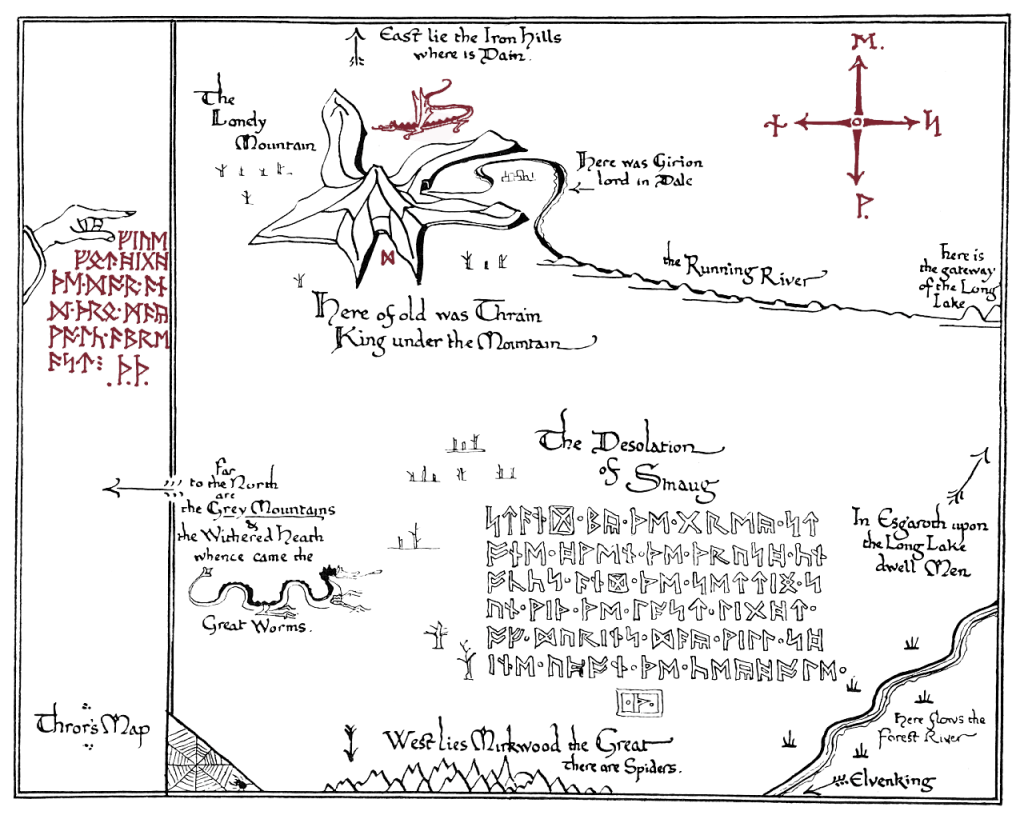

We can then imagine that this is what must appear as the “moon letters” on Thror’s map—

And this brings me to my final point.

In my last, in connection with the conlang (constructed language) toki pona, I mentioned the internet site Robwords, one of my favorite places for information and discussion about languages, primarily English, German, and French, but with some surprises (see last week’s “Simple Words” for more).

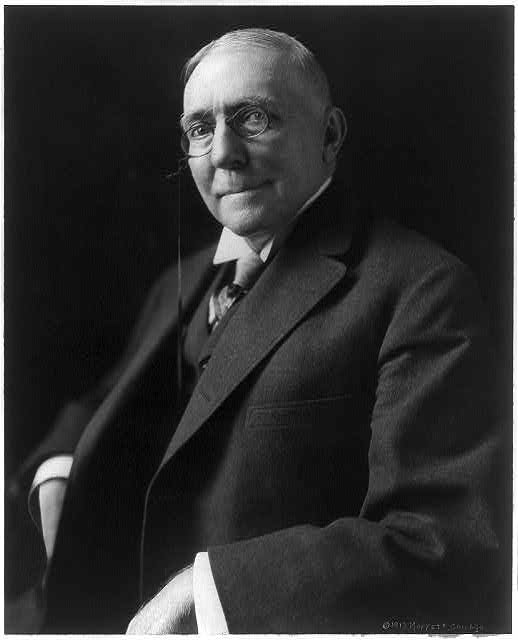

(This is Rob Watts, of Robwords)

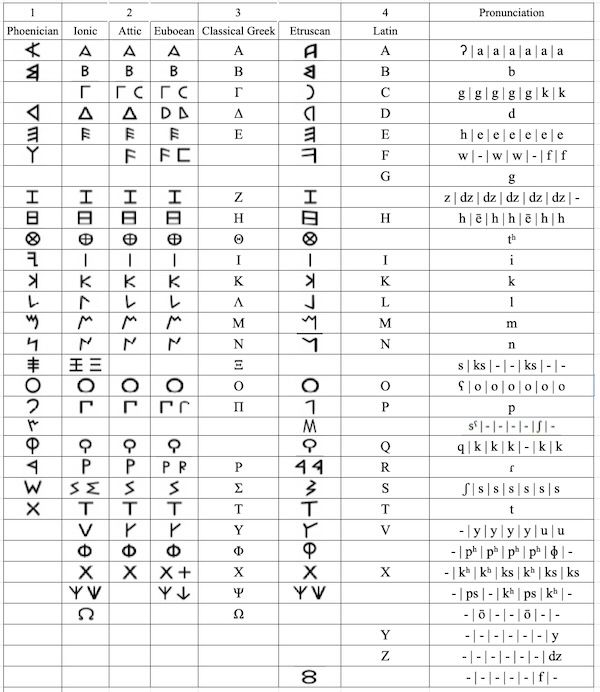

One of those surprises was toki pona, but, in another, Rob made the suggestion that the Roman alphabet, in which I’m writing this posting, was rotten for the English language, being adapted from the Greek alphabet (in turn adapted from the Phoenician alphabet) via the Etruscan alphabet,

and lacking letters for certain common English sounds like “th” and “sh” and “ng”.

In his playful way, he suggested that we’d be better off with the runic system, and specifically that Anglo-Saxon version, aka Futhorc.

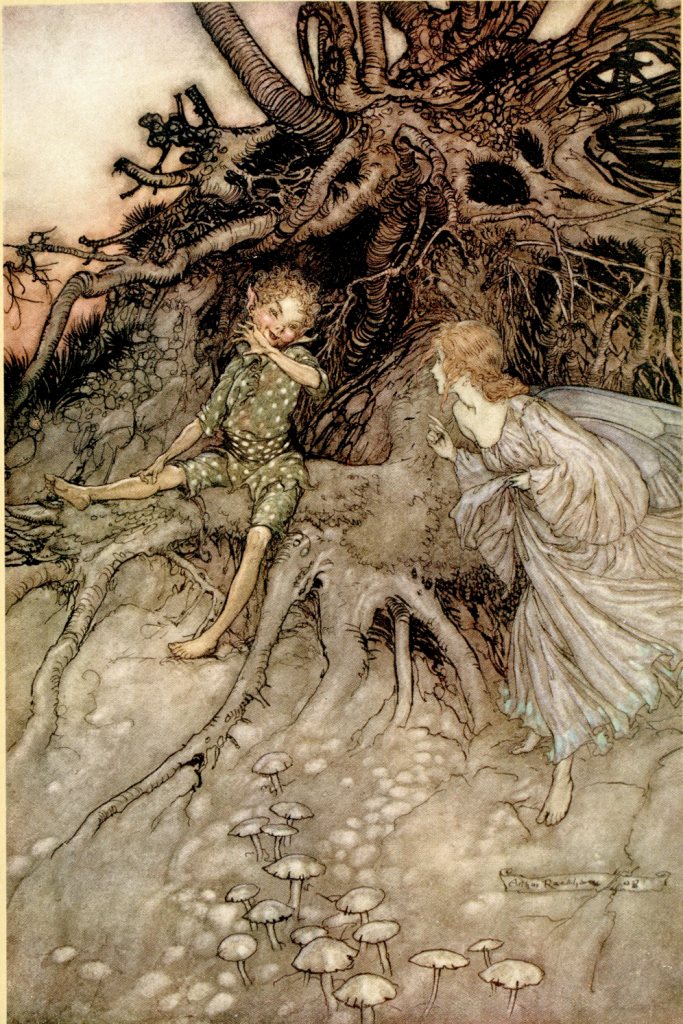

To prove his point, he cites something familiar to Tolkien readers—

and then proceeds to translate it, showing that it’s not in the language of the dwarves, as one might expect from a dwarvish map, but English (or, if you prefer, “the Common Speech”).

Watch the video, then, and see if you agree with Rob: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4npuVmGxXuk

And, if you’d like to try your hand at using the runes, here’s something to help—it’s a link to Harys Dalvi’s Old English runic keyboard: https://www.harysdalvi.com/futhorc/ Harys Dalvi’s website is full of really interesting language and computer stuff and just plain fun: https://www.harysdalvi.com/

Thanks, as always, for reading,

(ᚦᚫᛝᚳᛋ᛫ᚫᛋ᛫ᚫᛚᚹᛠᛋ᛫ᚠᚪᚱ᛫ᚱᛁᛁᛞᛁᛝ)

Stay well,

(ᛥᛠ᛫ᚹᛖᛚ)

Try runisizing today,

(ᛏᚱᚫᛁ᛫ᚱᚢᚾᛁᛋᛁᛋᛁᛝ᛫ᛏᚣᛞᛠ)

And remember that, as always, there’s

ᛗᚪᚱ᛫ᛏᚣ᛫ᚳᚢᛗ᛫ᛁᚾ᛫ᛞᚣ᛫ᚳᚣᚱᛋ

O

PS

At “wikiHow” there’s a pronunciation guide and a rather New Age interpretation of the Elder Futhark’s runes. It’s fun, but, as it sits to the left of such “How” guides as “telekinesis”, and “reading palms”, I myself would stick to the pronunciations! https://www.wikihow.com/Elder-Futhark-Runes

PPS

And how could I resist listing this: https://runicstudies.org/ the website for the American Association for Runic Studies? If you get hooked on runes—and I think that that would be quite easy to do, especially after playing on Harys’ website—this site has links in all directions.