Tags

A Midsummer Night's Dream, Arthur Rackham, Christina Rossetti, Elf Child, Fairies, Fairy Tale, George Macdonald, Goblin Feet, Goblin Market, Goblins, Historia Ecclesiastica, Hobgoblin, James Whitcomb Riley, John Garth, John Singer Sargent, King Edward's Horse, Little Orphan Annie, Orderic Vitalis, Pat Walsh, Psalm 91, Robin Goodfellow, The Crowfield Curse, The Crowfield Demon, The Hob and the Deerman, The Hobbit, The Lord of the Rings, The Princess and the Goblin, Tolkien, Tolkien and the Great War, Tolkien at Exeter College

As always, dear Readers, welcome!

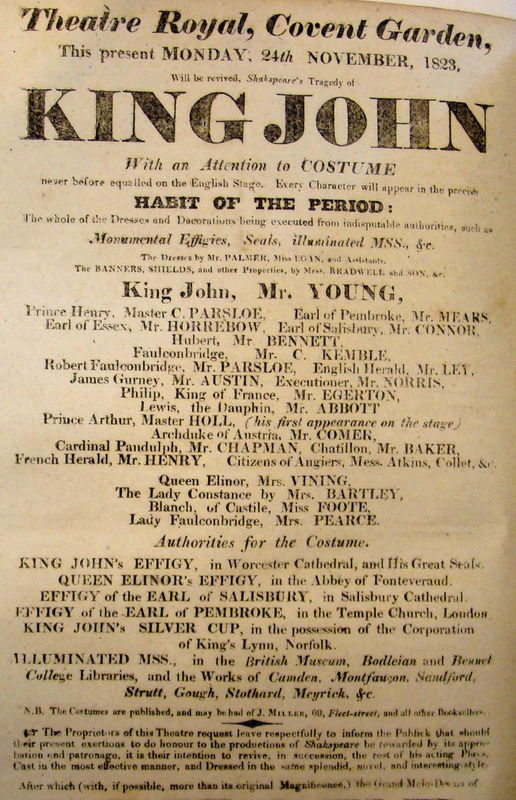

In our last, we were talking about JRRT’s 1915 poem, “Goblin Feet” its origins, original publication, and context.

In this, we want to think out loud a bit about the idea of goblins in general.

Although the poem was entitled “Goblin Feet”, Tolkien seemed not to focus so much on goblins—there are also other creatures from the Otherworld, including fairies and gnomes and even leprechauns (not to mention bats—called by their old country name “flitter-mice”—and beetles and coneys).

In this posting, however, we’re going to stick to goblins—well, and hobgoblins—but more about those later.

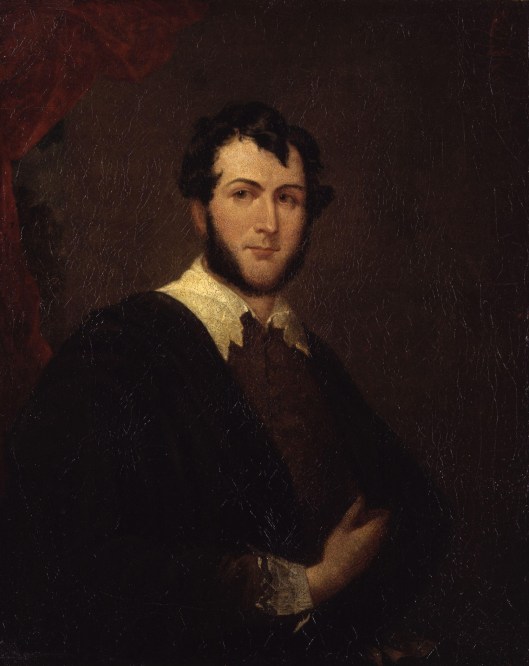

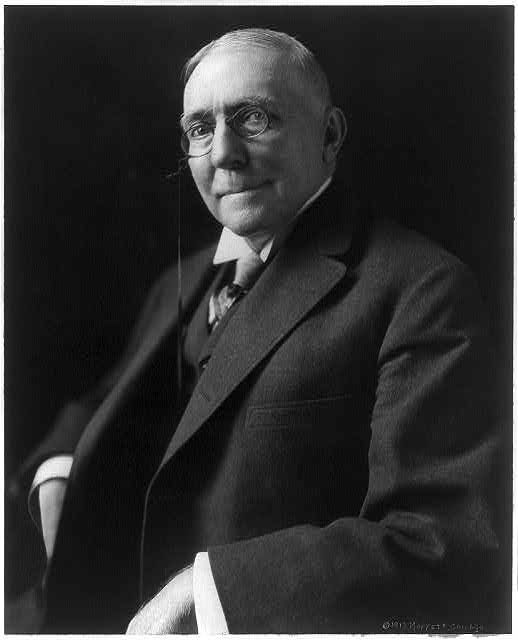

We first encountered goblins as very small children when a teacher read us a poem by the American poet, James Whitcomb Riley (1849-1916).

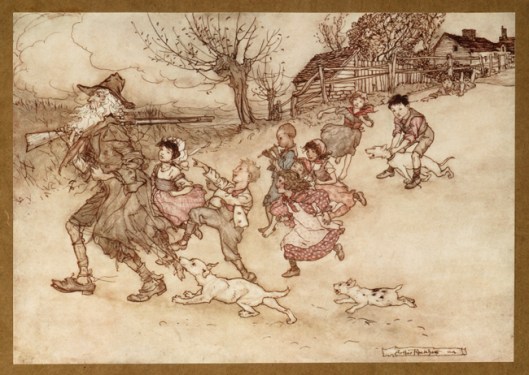

(We can’t resist a second picture. This is by one of our favorite late-19th-early-20th-c. American Painters, John Singer Sargent—1856-1925.)

This poem, first entitled “Elf Child”, originally appeared in a newspaper in 1885. After that, it was meant to be “Little Orphan Allie”, but, owing to a typsetter’s error, it gained its present title, which it’s had ever since.

Little Orphant Annie – Poem by James Whitcomb Riley

To all the little children: — The happy ones; and sad ones;

The sober and the silent ones; the boisterous and glad ones;

The good ones — Yes, the good ones, too; and all the lovely bad ones.

Little Orphant Annie’s come to our house to stay,

An’ wash the cups an’ saucers up, an’ brush the crumbs away,

An’ shoo the chickens off the porch, an’ dust the hearth, an’ sweep,

An’ make the fire, an’ bake the bread, an’ earn her board-an’-keep;

An’ all us other childern, when the supper-things is done,

We set around the kitchen fire an’ has the mostest fun

A-list’nin’ to the witch-tales ‘at Annie tells about,

An’ the Gobble-uns ‘ll git you

Ef you

Don’t

Watch

Out!

Wunst they wuz a little boy wouldn’t say his prayers,–

An’ when he went to bed at night, away up-stairs,

His Mammy heerd him holler, an’ his Daddy heerd him bawl,

An’ when they turn’t the kivvers down, he wuzn’t there at all!

An’ they seeked him in the rafter-room, an’ cubby-hole, an’ press,

An’ seeked him up the chimbly-flue, an’ ever’-wheres, I guess;

But all they ever found wuz jist his pants an’ roundabout:–

An’ the Gobble-uns ‘ll git you

Ef you

Don’t

Watch

Out!

An’ one time a little girl ‘ud allus laugh an’ grin,

An’ make fun of ever’ one, an’ all her blood-an’-kin;

An’ wunst, when they was ‘company,’ an’ ole folks wuz there,

She mocked ’em an’ shocked ’em, an’ said she didn’t care!

An’ jist as she kicked her heels, an’ turn’t to run an’ hide,

They wuz two great big Black Things a-standin’ by her side,

An’ they snatched her through the ceilin’ ‘fore she knowed what she’s about!

An’ the Gobble-uns ‘ll git you

Ef you

Don’t

Watch

Out!

An’ little Orphant Annie says, when the blaze is blue,

An’ the lamp-wick sputters, an’ the wind goes woo-oo!

An’ you hear the crickets quit, an’ the moon is gray,

An’ the lightnin’-bugs in dew is all squenched away,–

You better mind yer parunts, an’ yer teachurs fond an’ dear,

An’ churish them ‘as loves you, an’ dry the orphant’s tear,

An’ he’p the pore an’ needy ones ‘at clusters all about,

Er the Gobble-uns ‘ll git you

Ef you

Don’t

Watch

Out!

In some ways, this is a typical Victorian moral poem: children better behave, or… But, instead of being in “proper” English, it’s been told in the dialect of the US state of Indiana and this was something for which Riley was well-known, having written numbers of poems in the so-called “Hoosier” dialect. (This includes what looks like a misprint for the proper spelling “orphan”.)

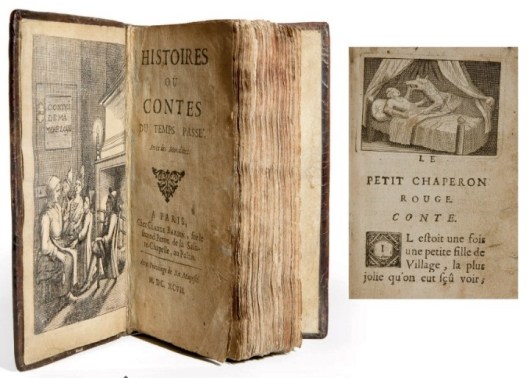

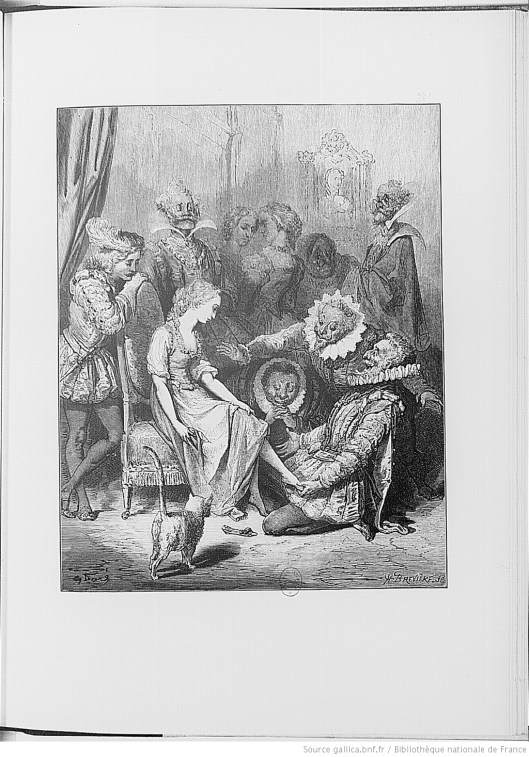

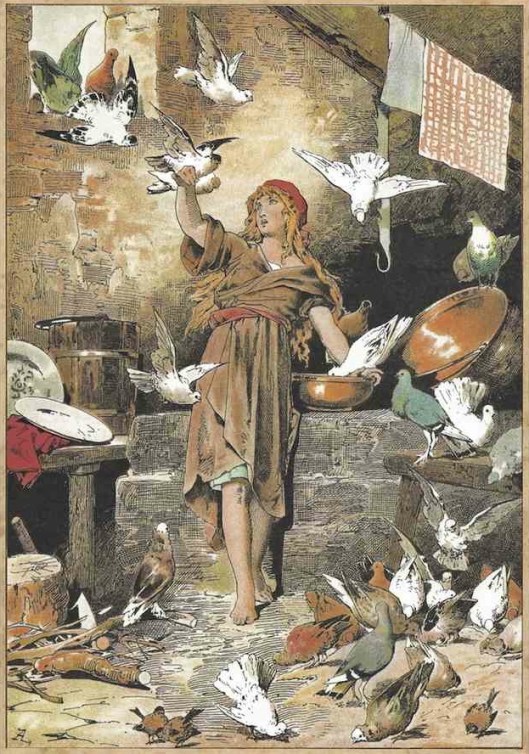

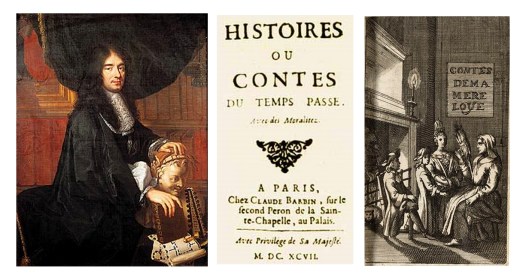

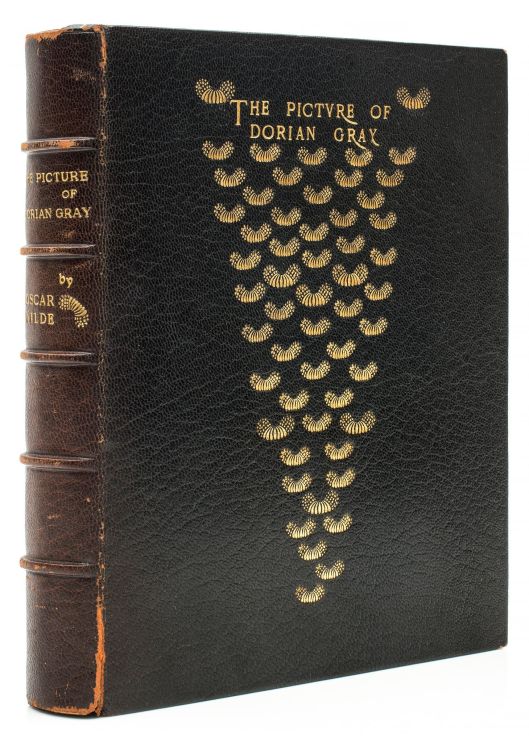

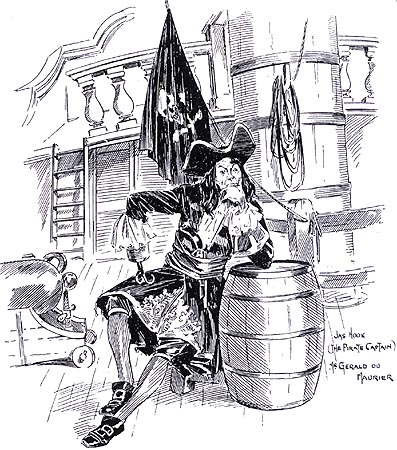

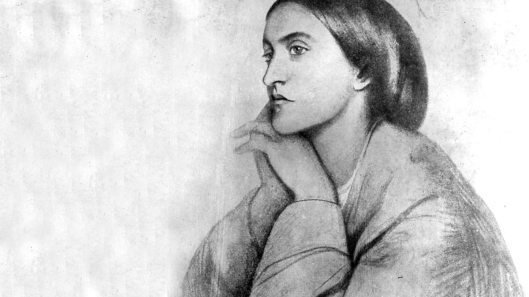

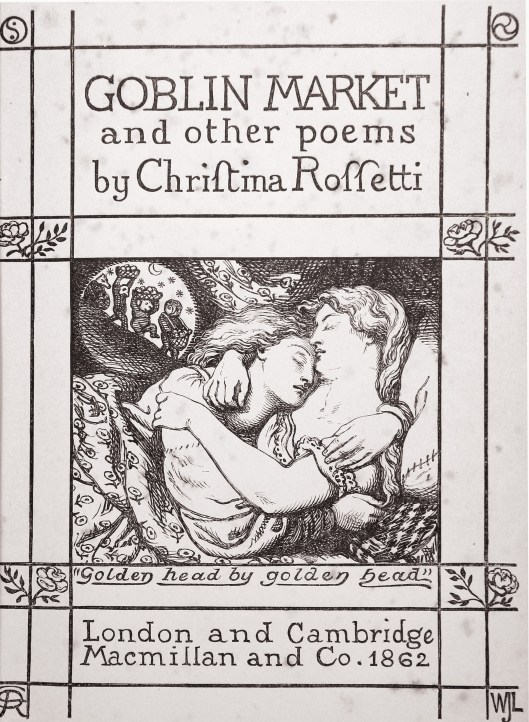

Our acquaintance with goblins has continued to be literary, from Christina Rossetti’s (1830-1894)

Goblin Market (1862)

to George Macdonald’s (1824-1905)

1872 fantasy novel, The Princess and the Goblin.

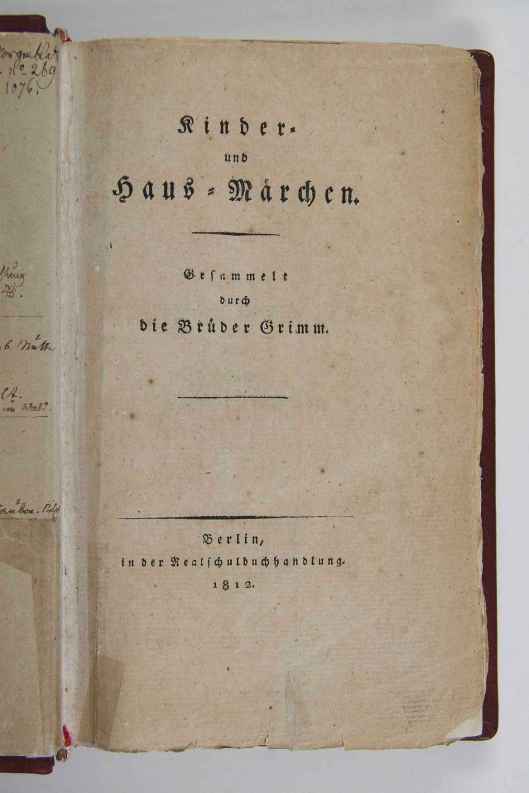

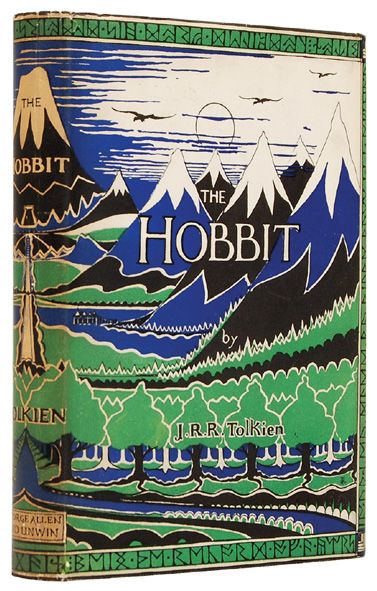

Our biggest—and longest—exposure, of course, was in The Hobbit (1937).

Goblins turn up from the moment Bilbo and the dwarves fall into their hands in Chapter 4, “Over Hill and Under Hill” and we see them again in their pursuit of the party once they’ve escaped the goblin stronghold and finally at the Battle of the Five Armies. At their first appearance, they are described as “great ugly-looking goblins” and, unlike the nimble-footed creatures of Tolkien’s 1915 poem, these have flat feet and flap them as they move. They live in a monarchy, ruled (for the moment) by a king described as “a tremendous goblin with a huge head”.

So far, we might see that as traditional nightmarish beings, like the “great big Black Things” in stanza 3 of Riley’s poem, but JRRT does something further and very interesting with them. This first novel was written in the 1930s, only twenty years after the Great War which had ruined much of western Europe and killed all but one of Tolkien’s oldest friends, and the emotional scar was still fresh, it seems. He was too humane (and too wise) to blame Germany for what had happened, but it’s clear that he wouldn’t excuse the Industrial Revolution and the goblins become a stand-in for all the worse of it:

“Hammers, axes, swords, daggers, pickaxes, tongs, and also instruments of torture, they make very well, or get other people to make to their designs, prisoners and slaves that have to work till they die for want of air and light. It is not unlikely that they invented some of the machines that have since troubled the world, especially the ingenious devices for killing large numbers of people at once, for wheels and engines and explosions always delighted them, and also not working with their own hands more than they could help; but in those days and those wild parts they had not advanced (so it is called) so far.” (The Hobbit, Chapter 4, “Over Hill and Under Hill”)

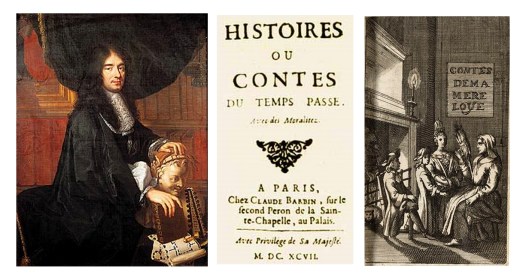

The word “goblin” has a rather mysterious etymological history and, like so many early words, that history is a murky one, full of guesses and suggestions. A little research produces the explanation that the word first seems to appear in Latin, in Orderic Vitalis’ (1075-c1142) Historia Ecclesiastica, Book 5, Chapter 7, in which, while reviewing the life of the early French saint, Taurinus, (lived c.400AD), Orderic mentions a demon whom the saint has vanquished, but which still haunted the area around the town of Evreux in Normandy, a demon the locals called “gobelinus”.

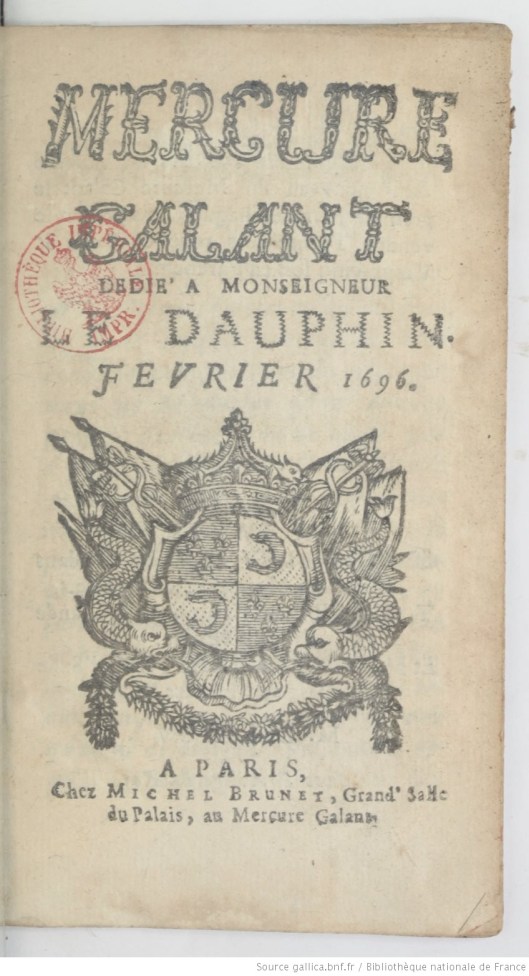

A century later, in the long Old French poem on the Third Crusade (1189-1192) of Ambroise of Normandy (who lived at the end of the 12th century), a noted figure in the actual history of the period, Balian d’ Ibelin, is referred to as being “more false than a gobelin” (L’Histoire de la Guerre Sainte, line 8710), with no explanation, suggesting that readers would be aware of what a gobelin was (and that he wasn’t trustworthy).

The word first appears in English in John Wycliffe’s translation of the Bible in the late 14th century, in Psalm 91, in which a God-fearing person will never be afraid of various things, including

“of a gobelyn goyng in derknisses”.

If 14th-century people knew what this creature was, we wonder whether it was still clear to people two centuries later—the older standard English translation (the so-called “King James Bible”, 1611) translates this as

“the pestilence that walks in darkness”

(which actually is close to the Hebrew original, as best as we can make out, as we don’t, unfortunately, read Hebrew—see this LINK to read for yourself.)

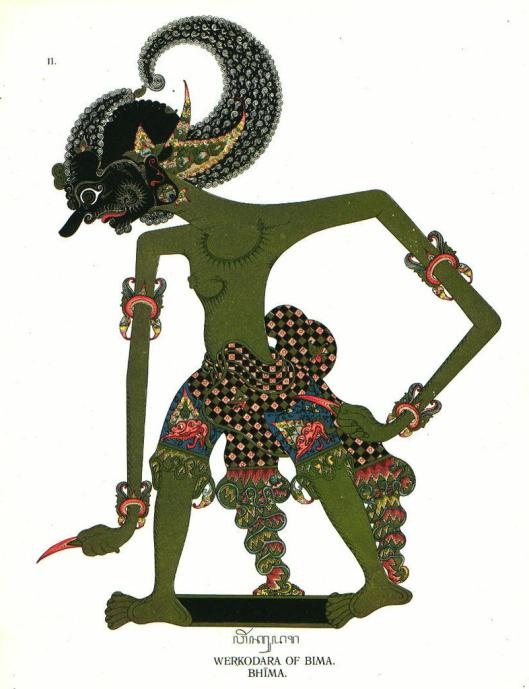

In the preface to the 1951 second edition of The Hobbit, Tolkien gives his own gloss, based upon the word he will employ almost entirely in The Lord of the Rings for such creatures:

“Orc is not an English word. It occurs in one or two places but is usually translated goblin (or hobgoblin for the larger kinds). Orc is the hobbits’ form of the name given at that time to these creatures…)

thus blending villains from 1937 with those readers would soon see in his new work, The Lord of the Rings (1954-1955).

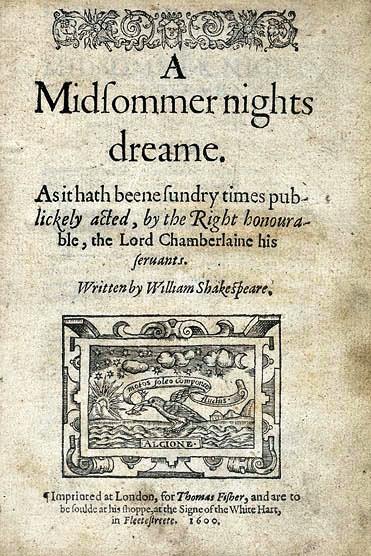

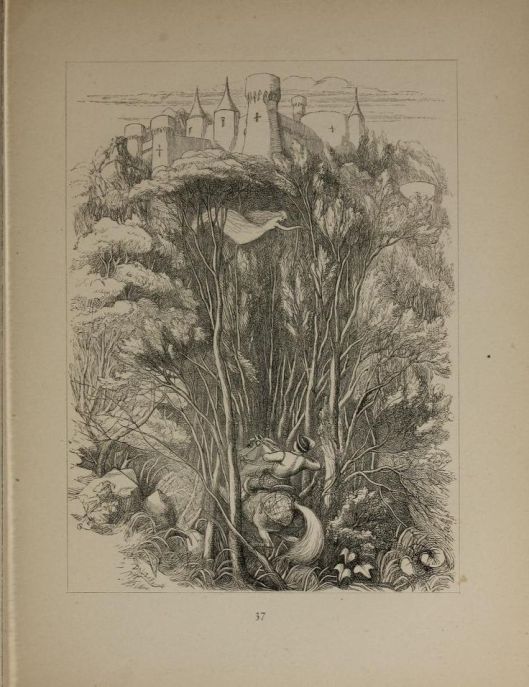

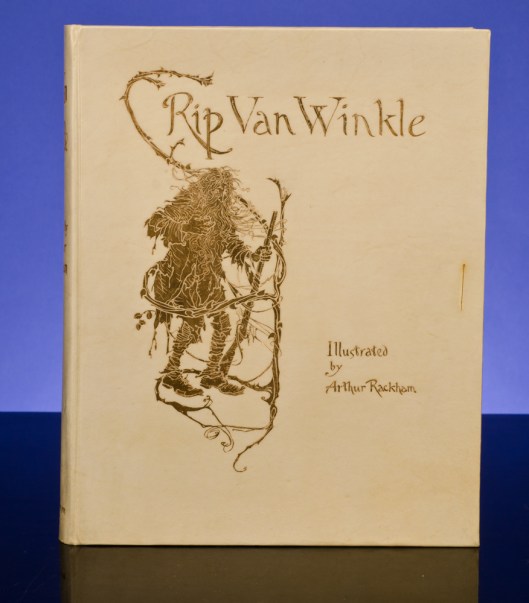

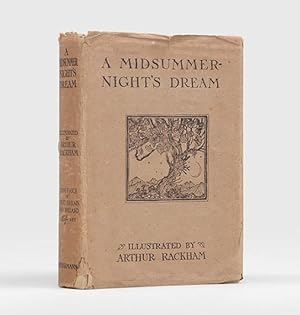

“Hobgoblin” brings us to our conclusion, however. As in the case of “goblin”, things get murky here, too, with some stating that, as “Hob” is an old nickname for “Robert” (compare “Hodge” as an old nickname for “Roger”), so a hobgoblin is related to “Robin Goodfellow”, (“Robin” being another nickname for “Robert”) aka the Puck we see in A Midsummer Night’s Dream (1595-96?).

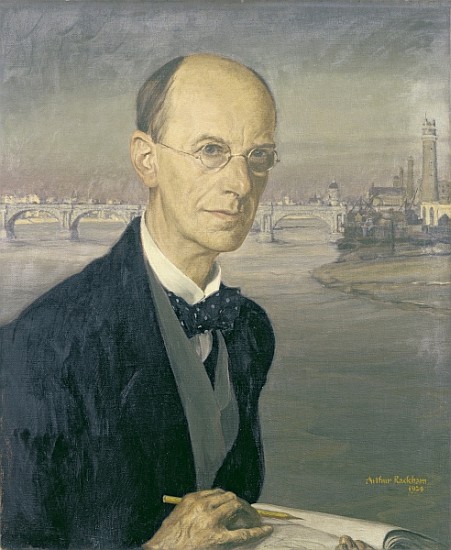

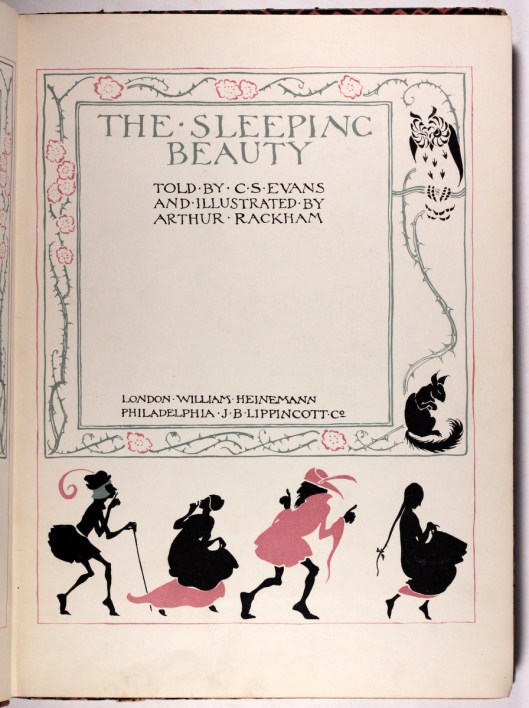

(This image is from Arthur Rackham’s (1865-1939) 1933 version of the play.)

Hobgoblins sometimes appear as prickly household helpers (rather like Dobby in the Harry Potter books), and those who want to associate the “hob” of “hobgoblin” with the “hob” (earlier “hubbe”), “the side of a fireplace” see that prefix as suggesting that “hobgoblins” might be a subset of “goblins” in general.

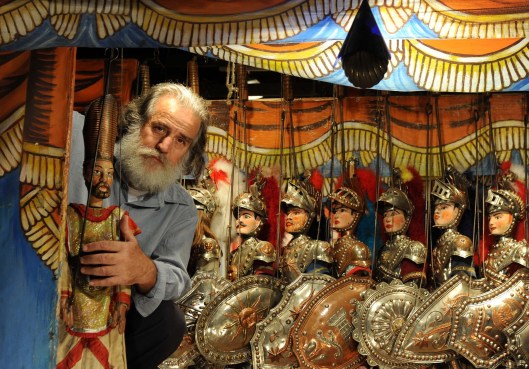

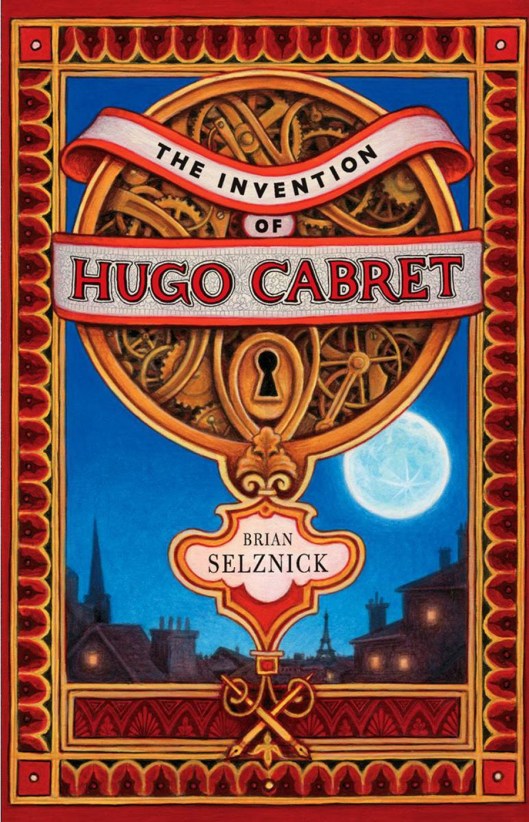

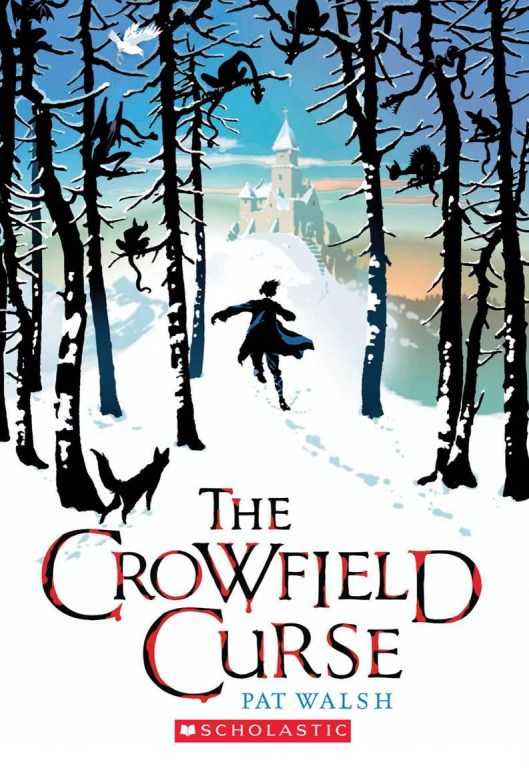

For us, however, a “hob” is a character in an on-going series we recommend to our readers. These are novels set in and around a decaying medieval monastery in 1347 and the haunted world around it, written by Pat Walsh, an archaeologist/fantasy author.

The first two in the series are The Crowfield Curse (2010) and The Crowfield Demon (2011)

In this series, the hero, Will, an orphan, discovers a wounded creature and brings it back to the monastery. It’s a hob—and will be a major character as the series develops. In 2014, Walsh began a new series with The Hob and the Deerman.

Walsh has promised a third book in the Crowfield series, Crowfield Rising, but it has yet to appear—unlike our next posting, which will appear (provided that there is no space alien invasion or implementation of Order 66 or Sauron producing a new ring), next week.

Till then, thanks, as ever, for reading.

MTCIDC

CD

PS

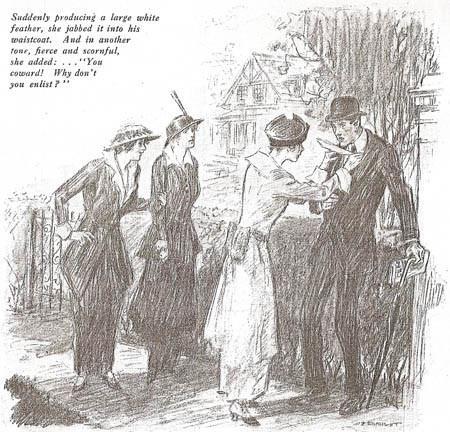

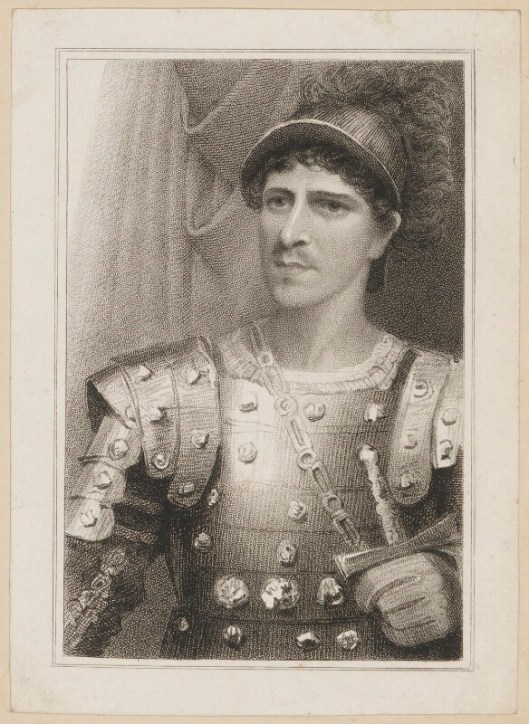

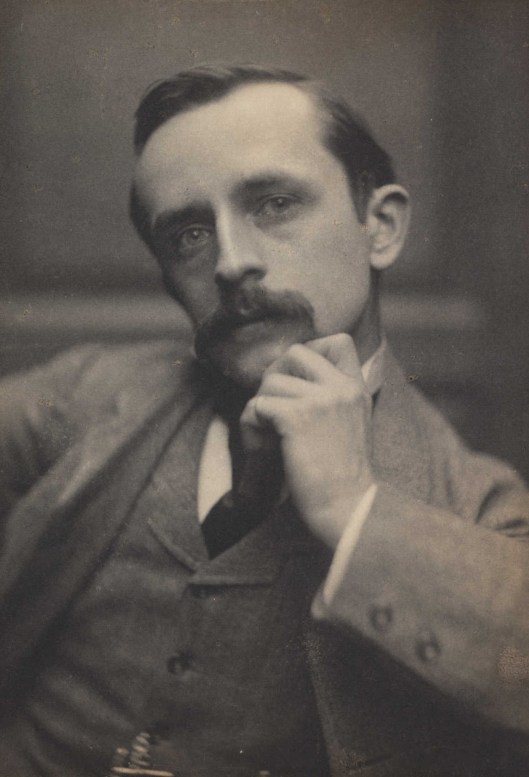

In our last, we mistakenly identified a photo of JRRT in a uniform which we thought belonged to a unit at his alma mater, King Edward’s School, as the caption with it said “1907”. It seemed odd to us, however, because it had the look of a cavalry unit (the bandoleer across the chest was common during the period for cavalry and for artillerymen) and, for all that he writes admiringly of horses, we had no sense that he himself was ever a horseman. This nagged at us until we did a little research and realized our mistake: the uniform was for King Edward’s Horse, the equivalent of a national guard/volunteer unit raised before the Great War. Tolkien was a member of this at the beginning of his Oxford career in 1911, but later resigned. John Garth’s two really useful books, Tolkien at Exeter College and Tolkien and the Great War, set us straight.

PPS

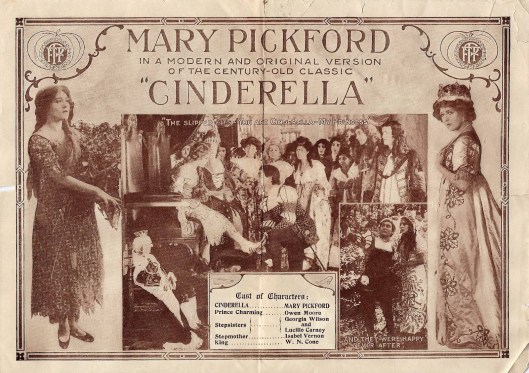

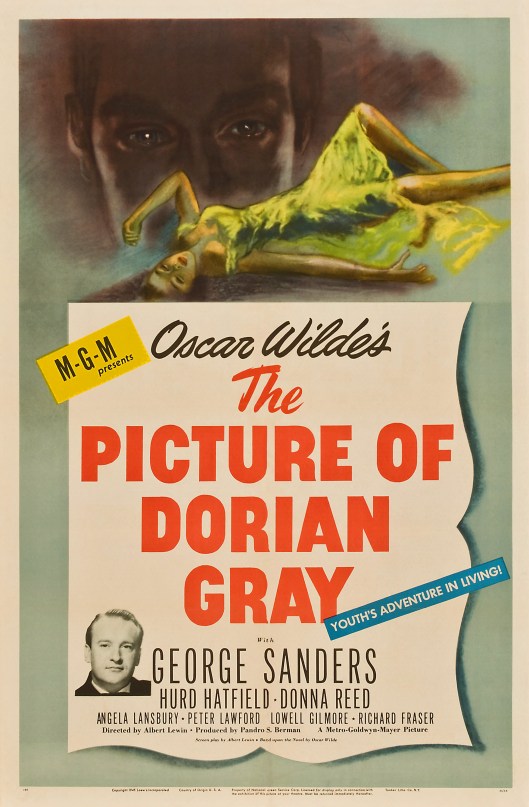

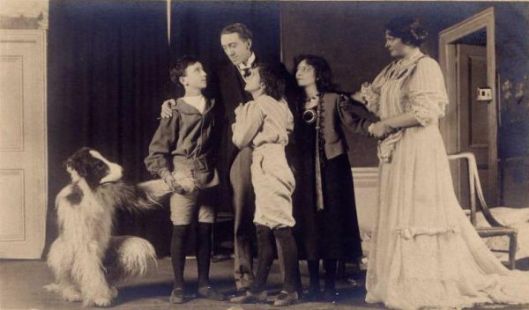

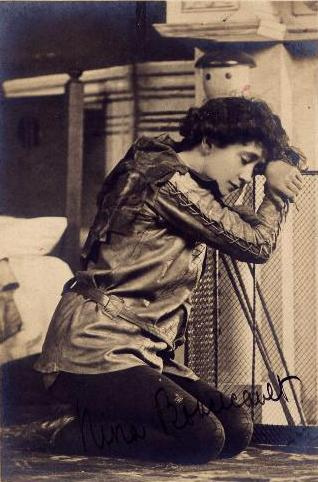

If you read us regularly, you know that we have a special love for early, silent film While researching this posting, we learned that, in 1918, a film was made based upon “Little Orphant Annie” and that a copy of it has survived for us to see. Here’s a poster and a still.