Tags

Adventure, Among Gnomes and Trolls, Bilbo, comic, Gandalf, Gollum, humor, John Bauer, Middle-earth, Pēro & Pōdex, Roast Mutton, Stone Trolls, The Hobbit, The Lord of the Rings, Through the Looking-Glass, Tolkien, Tommies, trolls, Victorian Drawing Room

Dear Readers, welcome, as always.

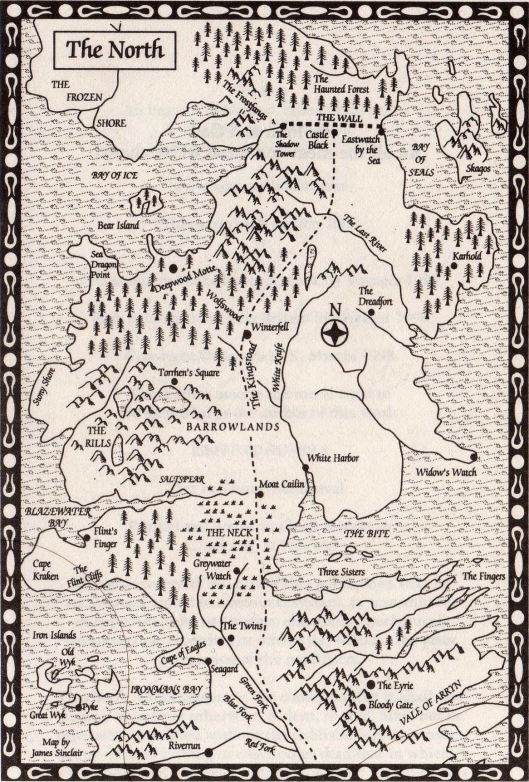

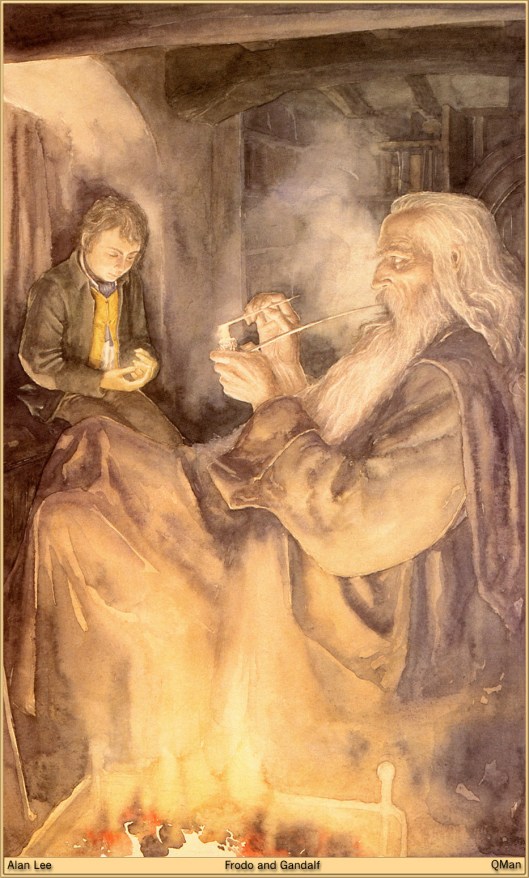

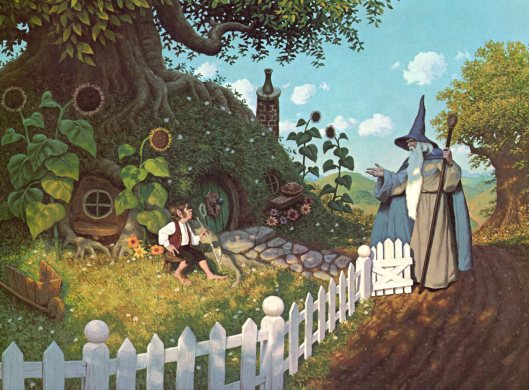

This is going to be a two-part posting because– well, it began as one thing, and then became another. We were thinking about Gollum, not as the grim and tormented figure we know from The Lord of the Rings, but rather as the muttering, riddling cave-dweller of The Hobbit. We were wondering if we could see Gollum not only as menacing, but as comic, as well.

Then, however, we began to think about other such figures, and one of us said to the other, “What about the trolls in The Hobbit?”. The other replied, “we see them before we see Gollum. Maybe we should start with them.”

And so we shall.

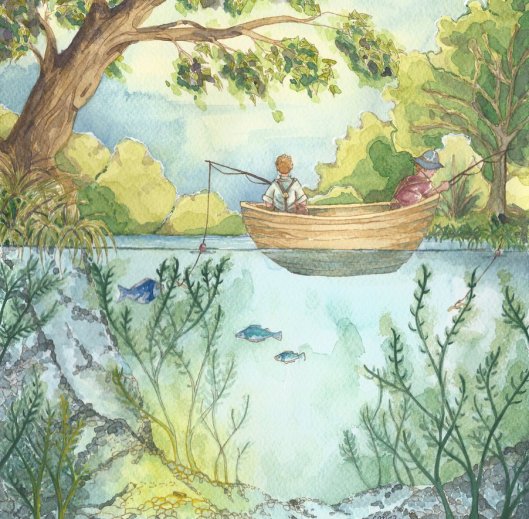

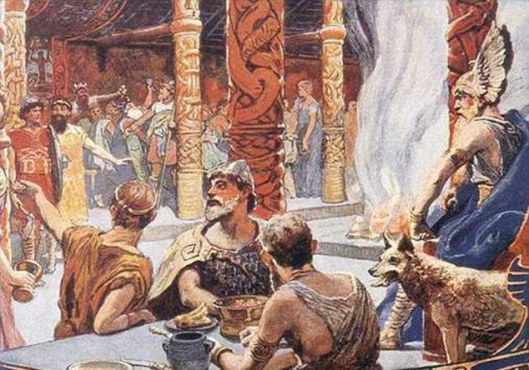

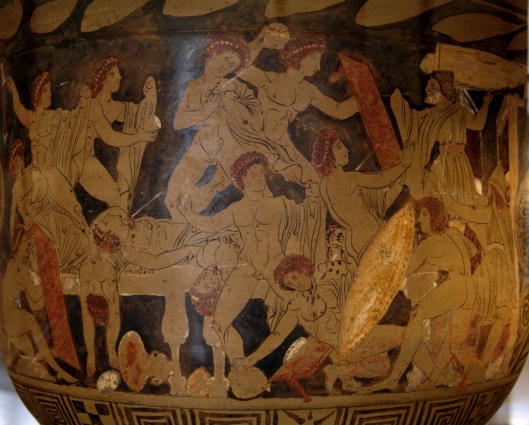

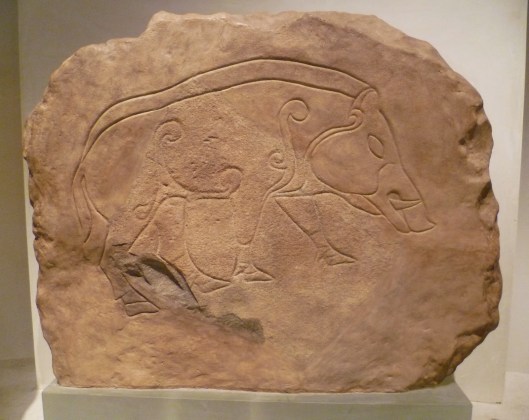

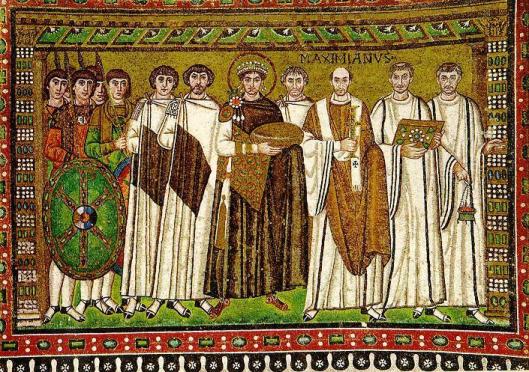

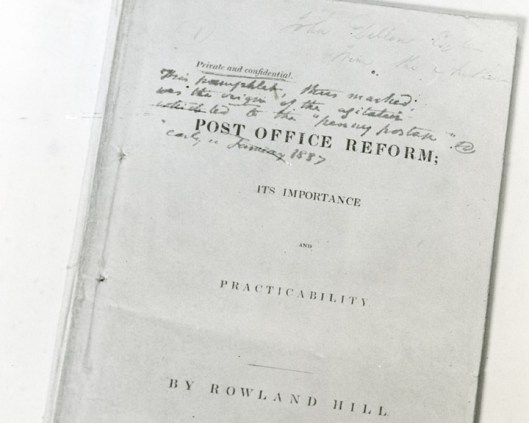

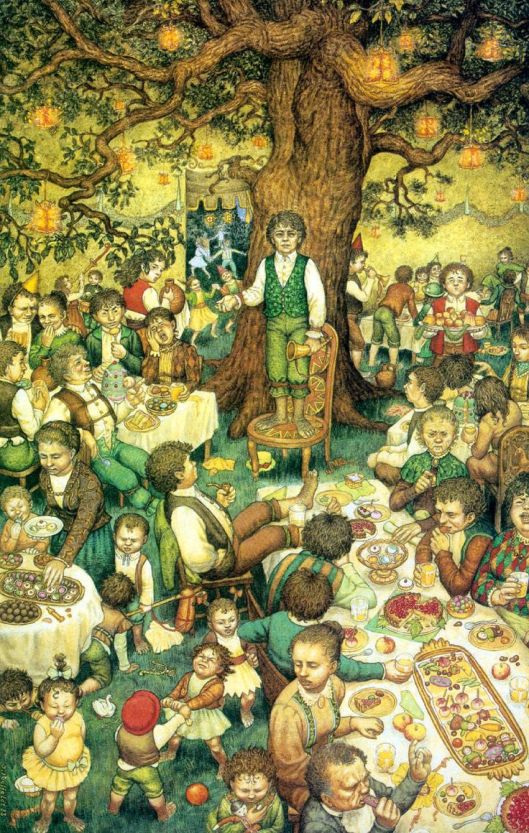

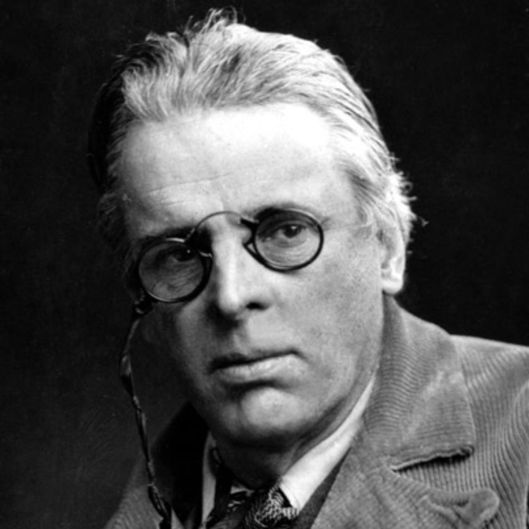

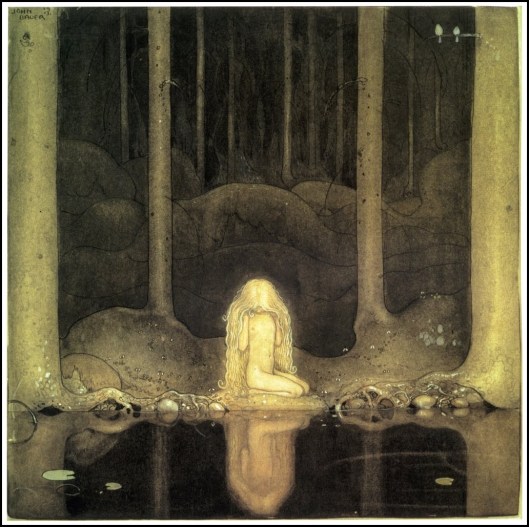

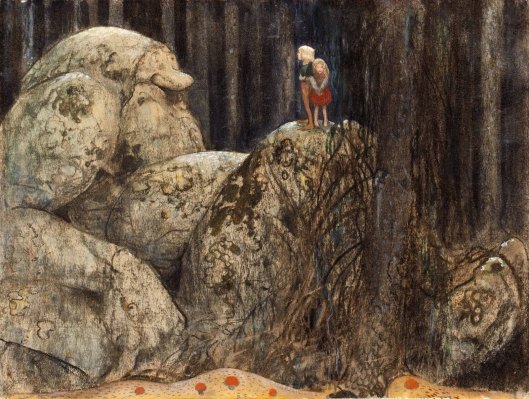

It’s clear where Tolkien got his trolls– they’re all over the fairy tales he had been reading since childhood, and they form a component of the traditional Scandinavian literature in which he had been interested for nearly as long. They are commonly large, and not terrifically bright, and often possess an anxiety about daylight. One of our favorite illustrators of such creatures is John Bauer (1882-1918), who, among other works, contributed illustrations to an ongoing series of volumes appropriately titled Among Gnomes and Trolls. Here, for example, is one of his depictions of the latter.

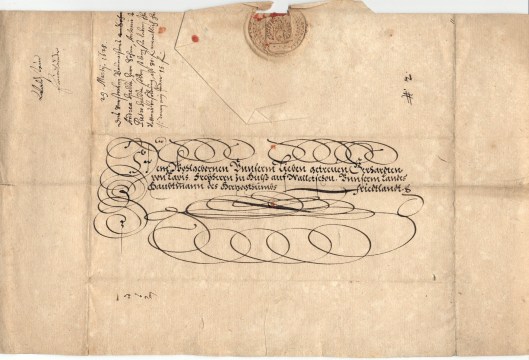

And, because we can’t resist– can we ever? Here are a couple more illustrations by Bauer.

Even before The Hobbit, however, Tolkien had produced a literary troll. In 1926, he wrote the first version of a poem to be sung to the folk song “The Fox Went Out”, called “Pēro & Pōdex”(“Boot and Bottom”). It survives in a later version in chapter 12 of Book 1 of The Lord of the Rings, beginning “Troll sat alone on his seat of stone”.

In The Hobbit, the trolls are grouped around a fire, drinking and eating and immediately recognizable:

“But they were trolls. Obviously trolls. Even Bilbo, in spite of his sheltered life, could see that: from the great heavy faces of them, and their size, and the shape of their legs, not to mention their language, which was not drawing-room fashion at all, at all.” (The Hobbit, Chapter 2, “Roast Mutton”)

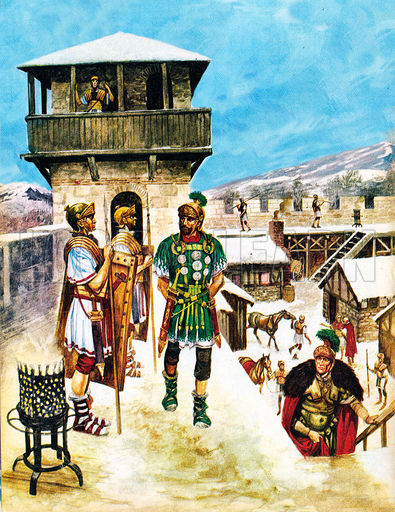

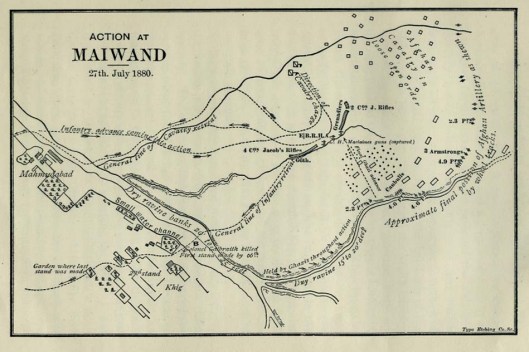

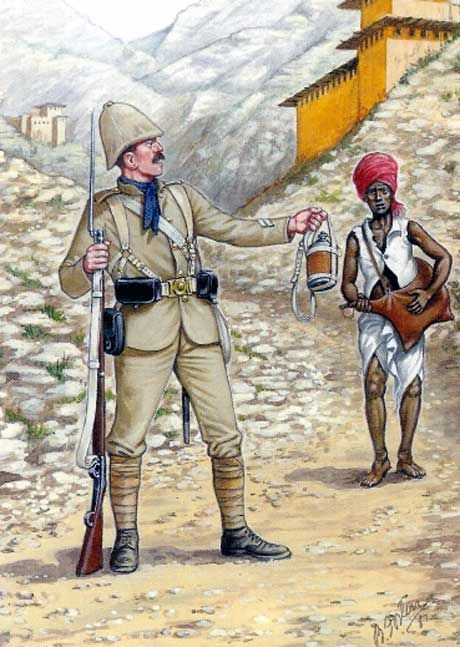

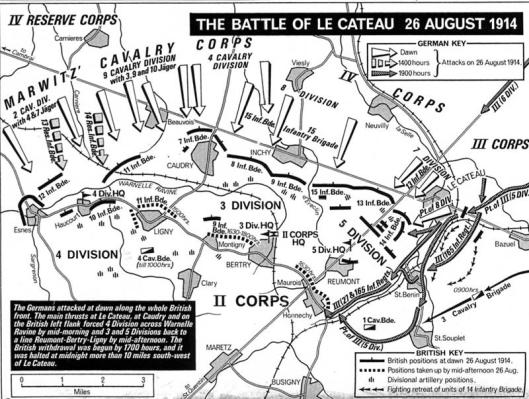

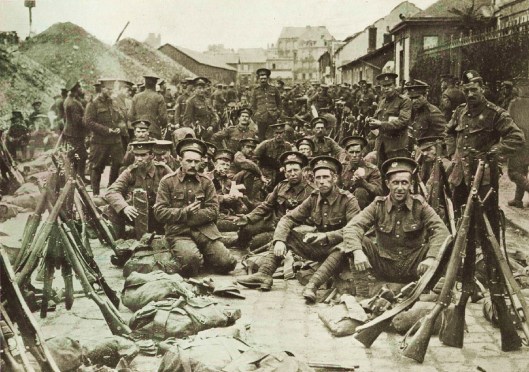

Douglas Anderson, in his invaluable The Annotated Hobbit, says that “Tolkien presents the Trolls’ speech in a comic, lower-class dialect” (70). In fact, we wonder whether, as in the case of the later orcs in The Lord of the Rings, we are not seeing a reflection of the speech of some of the Tommies whom Tolkien had commanded in the Great War.

” ‘Mutton yesterday, mutton today, and blimey, if it don’t look like mutton again tomorrer,’ said one of the trolls.

‘Never a blinking bit of manflesh have we had for long enough,’ said a second. ‘What the ‘ell William was a-thinkin; of to bring us into these parts at all, beats me – and the drink runnin’ short, what’s more,’ he said jogging the elbow of William, who was taking a pull at his jug” (The Hobbit, Chapter 2, “Roast Mutton”).

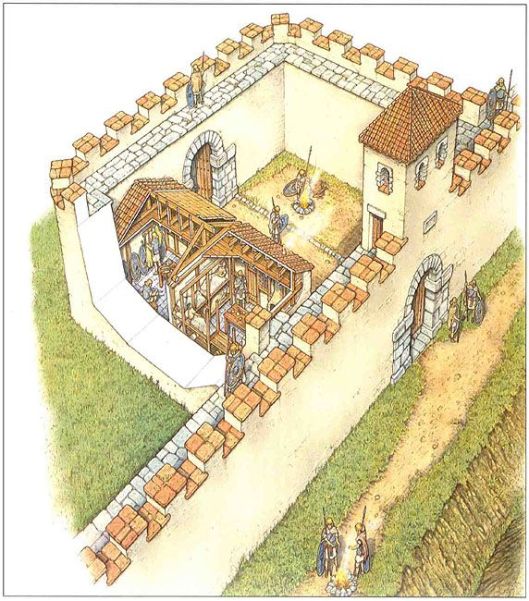

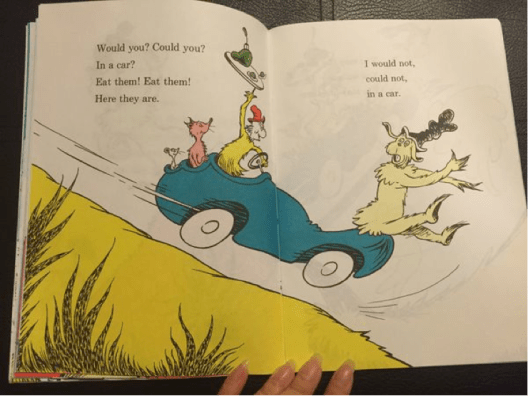

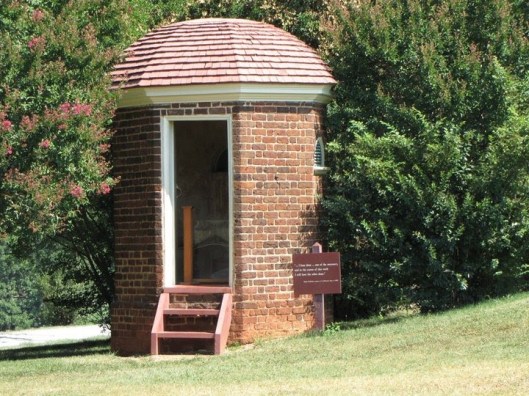

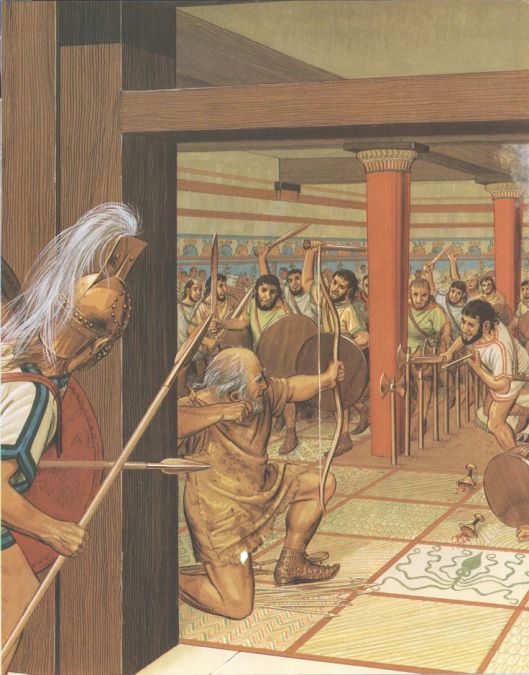

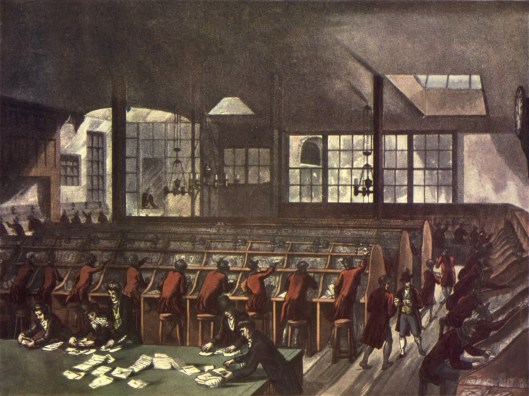

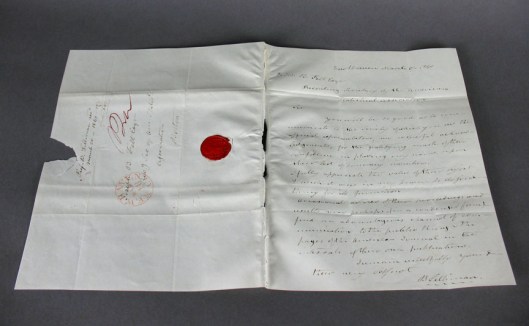

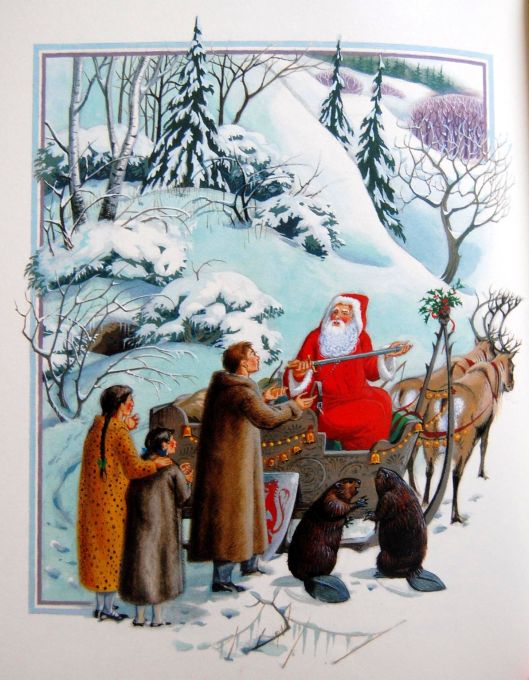

Besides what sounds like a reference to a line in Through the Looking-Glass (1871), “The rule is, jam to-morrow and jam yesterday – but never jam to-day,” with their “blimey” and “blinking”, the trolls are immediately labeled by their speech as lower-class, potentially thuggish, and certainly not people invited to a formal drawing room like this–

Of course, we might ask ourselves, why should trolls talk like that anyway? And we might then reply, because Tolkien is mixing language for comic effect. Bilbo, Gandalf, and the dwarves speak in non-dialect standard English. Therefore, there’s an especially strong contrast here. As well, what the trolls are saying can be funny in itself, as when William says to the discontented other trolls,

” ‘Yer can’t expect folk to stop here for ever just to be et by you and Bert. You’ve et a village and a half between yer, since we come down from the mountains. What more d’yer want?’ ” (The Hobbit, Chapter 2, “Roast Mutton”).

Here, we have comic exaggeration combined with the frustrated defensiveness of a leader whose tactics are being questioned by subordinates.

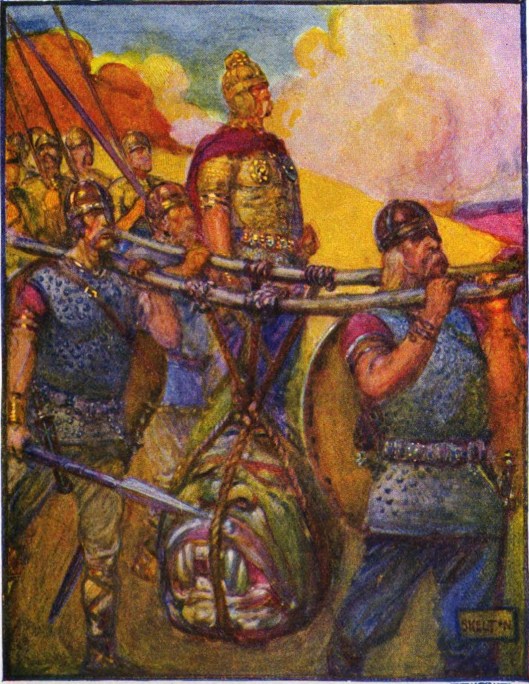

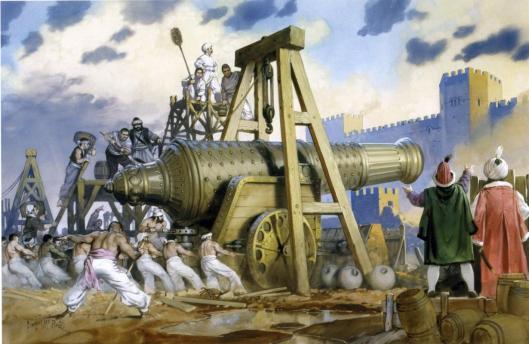

The tension grows as the scene progresses. Bilbo appears, is nabbed by a purse which sounds like the Trolls, the Trolls fall to fisticuffs while arguing over Bilbo and then over the dwarves whom they capture, and Gandalf, imitating various Troll voices, so stirs the pot that the Trolls never notice when the first beam of sunlight cuts across their clearing and they are petrified.

So, if we consider what the Trolls have been doing previously–“Never a blinking bit of manflesh have we had for long enough…” says one, as well as what they discuss doing not only to Bilbo, but to the whole of Thorin & Co., these could seem to be grim figures, indeed. Then again, they sound like comic cockneys, they have ludicrously-large appetites, and they are dim enough to be taken in very easily by Gandalf’s ventriloquism. So, grim and funny at the same time.

On the whole, humor is more an element in The Hobbit than in The Lord of the Rings, but we believe that perhaps because of his initial appearance in The Hobbit, Gollum may have both the menace and the humor, at times , of these gormless Trolls, as we hope to show in Part 2.

Thanks, as always, for reading,

MTCIDC,

CD