Tags

Andy Serkis, Ben Gunn, Bilbo, Deagol, Gollum, Received Standard English, Riddles in the Dark, Smeagol, The Hobbit, The Lord of the Rings, Tolkien, Treasure Island

Dear Readers, welcome, as always.

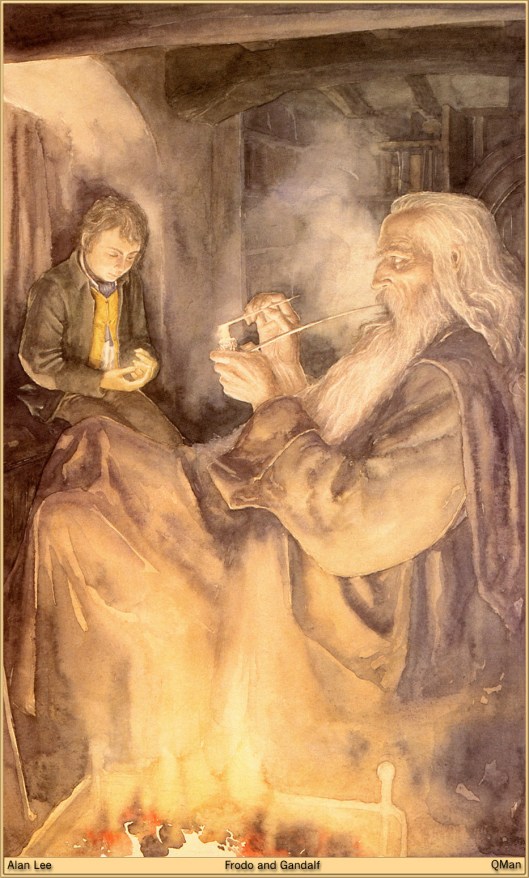

In the first part of this posting, we began to think out loud about the idea of characters in Tolkien who might combine menace and comedy. Our first idea had been to consider Gollum—

but not the Lord of the Rings Gollum, at least not at first glance.

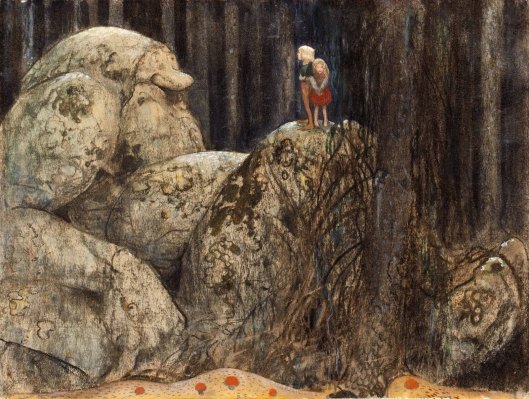

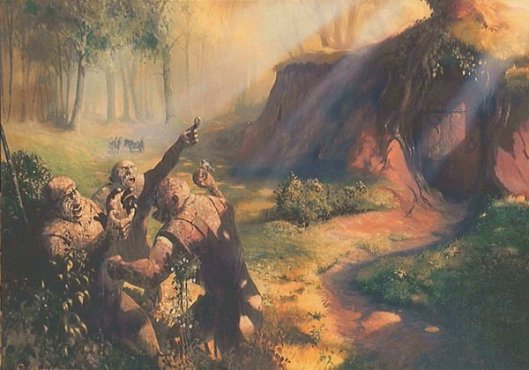

The idea then took us backwards to the large, rather dim trolls of The Hobbit, who certainly seemed to display that combination.

And The Hobbit brings us back to Gollum.

All Tolkien readers must know, we imagine, that the book which JRRT published in 1937 was a very different kind of book from what gradually grew up around it. Here, for example, is the beginning of the reader’s introduction to Smeagol (a name never used in The Hobbit, of course):

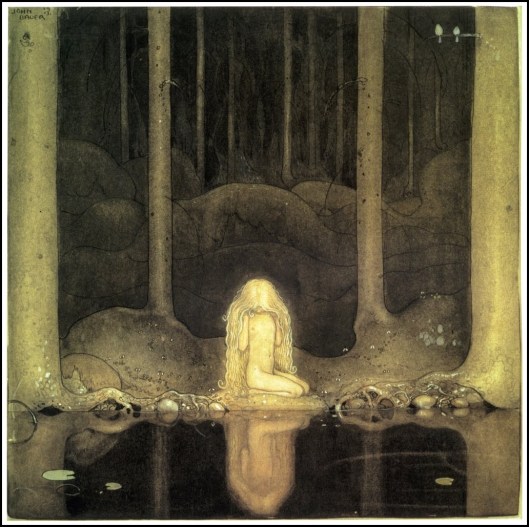

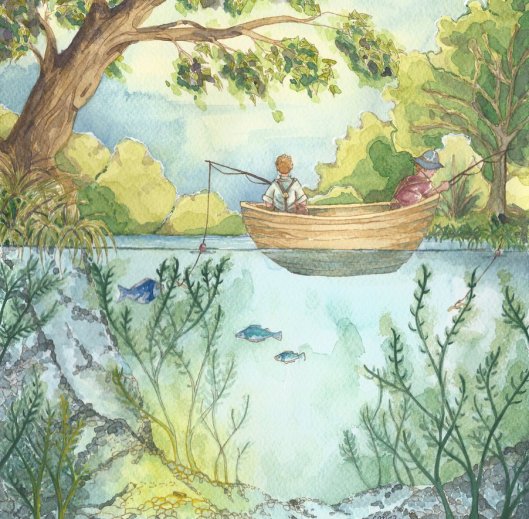

“Deep down here by the dark water lived old Gollum…” (The Hobbit, Chapter 5, “Riddles in the Dark”)

To us, this sounds like it could easily begin, “Once upon a time, deep down by the dark water, lived Old Gollum”, as if it were the opening of a fairy tale and The Hobbit was, of course, originally conceived of and written as a children’s book.

“Old Gollum”, by that name, might have been a cantankerous but lovable geezer—but the line continues, “a small slimy creature”. “Slimy” then leads to “dark as darkness, except for two big round pale eyes in his thin face…He liked meat too. Goblin he thought good, when he could get it; but he took care they never found him out. He just throttled them from behind…” And then, presumably, he ate them raw (as he does fish in The Hobbit and he would coneys in The Lord of the Rings), as Gollum’s level of civilization seems to begin and end with the little boat which he has—although where the materials came from for that is never explained. (Gandalf, in “The Shadow of the Past”, says that the Stoors and Fallowhides, to whom Gollum/Smeagol belonged, made boats out of reeds.)

In our last posting, we pointed to the speech of the trolls in The Hobbit as one possible source of humor.

Unlike the main characters, who spoke a Middle-earth version of RSE (Received Standard English), they displayed a number of the linguistic elements of lower-class London which are often used to show class—or even species?–difference (think of the orcs who carry off Merry and Pippin, for example) in Tolkien. If this is combined with the topics of their conversation—mainly about food, some of it sheep, but also both humans and dwarves—we then have what we set out to find, menace and humor.

As for Gollum, he certainly has a very distinctive form of speech. First, there’s his habit of carrying on a conversation with himself even in the presence of others. It reminds us of the talk of Ben Gunn,

who was marooned by Captain Flint in Stevenson’s Treasure Island (1881-2; 1883) and has clearly developed a similar habit:

“If you was sent by Long John,” said he, “I’m as good as pork and I know it. But where was you, do you suppose?” (Treasure Island, Chapter XV, “The Man of the Island”)

There are four other distinctive elements of Gollum’s speech. First, there is that gollum. The narrator says of it:

“And when he said gollum he made a horrible swallowing noise in his throat.” (The Hobbit, Chapter 5, “Riddles in the Dark”)

Andy Serkis, who is the voice (and movement) of Gollum in the Jackson films, has, in interviews, said that the noise he makes is modeled upon his cat throwing up a hairball. As Tolkien has called it “a horrible swallowing noise”, it would seem that this is, in fact, the opposite sound from what is wanted. So what should it sound like—that is, and still sound like “gollum”? The word has two syllables—perhaps we might think that the noise would depend upon which syllable bore the primary accent: GOL-lum or gol-LUM. To us, accenting the first has more of a choky feel to it and the second more of a froggy. (We also wonder, knowing Gandalf’s later explanation of how Smeagol acquired the Ring, whether, in fact, Smeagol is actually imitating the noise Deagol made as he struggled for breath.)

A second element is his incessant referring—in the 1937 edition—to himself as “my precious”. In the 1951 revision, and beyond, Gollum can call both himself and the Ring by the term, and we are of two minds about the change. On the one hand, the 1937 version reflects what interests us: a word of tender endearment mixed with a murderous intent, all within Gollum. On the other, the post-1951 version’s double usage presents us with a picture of a creature so enslaved to the Ring that he uses that term of endearment (and we also know, from Gandalf’s later explanation, that the Ring does not return the affection, making it even more horrible). As well, others touched by the Ring can be seen as infected by its power when they use the expression.

Third—and more potentially comic—is Gollum’s actual language. There are the odd expressions, sometimes based on actual older English expressions—“Bless us and save us” becomes “Bless us and splash us”, example. As well, there are the non-standard words like “bitsy” (a kind of diminutive) and plurals—“handses”, “eggses”, “pocketses”.

Fourth is the stressed sssssssssssssssssssssibilance. JRRT himself points to this in a letter to Rayner Unwin in a correction to the 1937 edition: “Not that Gollum would miss the chance of a sibilant.” (cited in Anderson, The Annotated Hobbit, 120, note 9)

Taken altogether, this makes for a very distinctive—and very different speaker from any other in The Hobbit (or The Lord of the Rings, for that matter) and this is clear from the very start of the conversation between Gollum and Bilbo:

“What iss he, my preciouss?”…

“I am Mr. Bilbo Baggins. I have lost the dwarves and I have lost the wizard, and I don’t know where I am and I don’t want to know, if only I can get away.” (The Hobbit, Chapter 5, “Riddles in the Dark”)

The menace is there in Gollum, from the very beginning:

“Bless us and splash us, my precioussss! I guess it’s a choice feast; at least a tasty morsel it’d make us, gollum!” (The Hobbit, Chapter 5, “Riddles in the Dark”)

And we would suggest that the humor is there, too, in the very same speech: the twisted expression, the self-address, the use of “my precioussss”, and the hissy sibilance. Tolkien, though personally drily witty, was not—nor intended to be—a comic writer. What he could do well, we suggest, is use that which interested him deeply—language and its expression—combine it, for contrast, with a certain darkness of theme, as here, and allow the reader to feel a kind of grim amusement in the balance–or imbalance–between what’s being said and how.

What do you think, dear readers?

Thanks, as always, for reading.

MTCIDC

CD