Tags

Aragorn, Aslan, C.S. Lewis, Catholicism, Gondor, Hobbits, Jadis, Medusa, Middle-earth, monotheism, Narnia, Oxford, religion, Sauron, secular, The Bird and the Baby, The Chronicles of Narnia, The Eagle and the Child, The Hobbit, The Inklings, The Lamb and Flag, The Lord of the Rings, the Pevensies, The Return of the Ring, The White Witch, Tolkien, White Tree

Dear Readers,

Welcome, as always.

This posting is a continuation of our last, in which we made a brief attempt to think about what the title “The Return of the King” might have meant for its author in his time.

In this posting, we want to expand that meaning from a secular king to one with more religious overtones.

We ourselves, as we’ve said before, are World Civ people, believing that all people in all times and places are and should be of interest and value to everyone. We are also pan-spiritual, thinking with Gandhi that, “I believe in the fundamental Truth of all great religions of the world.”

In the case of Tolkien, this meant Catholic Christianity, a form of monotheism. Of religion and The Lord of the Rings, he wrote in 1953:

“The Lord of the Rings is of course a fundamentally religious and Catholic work; unconsciously so at first, but consciously in the revision. That is why I have not put in, or have cut out, practically all references to anything like ‘religion’, to cults or practices, in the imaginary world. For the religious element is absorbed into the story and the symbolism.” Letters, 172.

He adds to this, in a letter to Houghton Mifflin, in 1955, that “It is a monotheistic world of ‘natural theology’. (Letters, 220). At the same time, however, he adds “I am in any case myself a Christian; but the ‘Third Age’ was not a Christian world. Letters, 220.

And yet we would suggest that there is not only more of a Christian theme, but also a Christian parallel with a book written at about the same time as the later stages of The Lord of the Rings and published slightly before it. This is C.S. Lewis’ The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe (1950).

As is well known, both Lewis and Tolkien

were members of a literary group in Oxford, the Inklings.

Lewis and Tolkien formed part of the permanent core, with other members coming and going over the years (1933-1949). The meetings were held in Lewis’ rooms at Magdalen College,

as well as at two local pubs, The Eagle and Child (called locally “Bird and Baby” or just “Bird”)

as well as The Lamb and Flag.

The purpose (besides refreshments) was literary discussion, both of others’ works and of their own, and an important feature was the reading aloud of works in progress. Lewis had been very supportive, both of The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings, but Tolkien had not been so enthusiastic in return. All the same, we would suggest that various elements of Lewis’ The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe and events around Gondor in Tolkien’s The Return of the King at times bear strong similarities.

In Lewis’ book, the main protagonists are four children, the Pevensies.

In Tolkien’s, there are four grown Hobbits, often mistaken, beyond the borders of the Shire, for children.

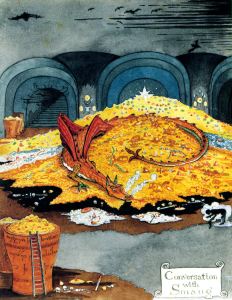

Both groups are on an errand which they barely understand and are faced with a supernatural enemy, the White Witch for the one, Sauron for the other. (There seems to be a lot of mirroring in all of this: the White Witch is already in Narnia and must be driven out. Sauron is outside Gondor and wants to get in, for example. The White Witch’s name is “Jadis”, by the way. Undoubtedly Lewis’ little linguistic joke: jadis in French means “formerly”, suggesting that even from the first time she appears, she’s already on her way out.)

(Notice, in the movie version of Jadis, the strong similarity between her and the Medusa. In fact, Jadis turns her enemies, when she can, to ice.)

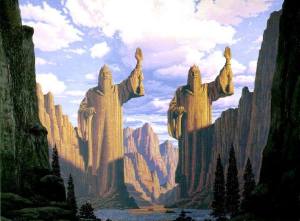

Before the current world of Narnia, to which the children come, there was a king who had been somehow ejected a century before. In Middle Earth, there has been no king in Gondor for ten times that. In Narnia, there has been winter for that century.

In Gondor, in Middle Earth, its symbol of growth and stability, the White Tree, has withered and died.

When the Pevensie children have been involved in the defeat of the White Witch, they will rule Narnia in the place of the true king, the lion Aslan.

For about a thousand years, stewards ruled Gondor in place of the king. (Another example of mirroring.)

When Lewis’ Aslan returns, it is from death, having sacrificed himself to save one of the Pevensie children.

Thus, Aslan, in effect, heals himself. When the king of Gondor, Aragon, appears, he heals others. (Tolkien would probably associate this with the old English custom of having the monarch touch people attacked with a disease called scrofula, or “the King’s evil”. We include a picture of Queen Mary—1516-1558—doing so.)

When Aslan appears, spring returns to Narnia.

When Aragorn claims the throne, he and Gandalf discover a sapling of the old tree on Mindolluin, bring it down, and plant it and it soon flowers.

We’re sure that there are other parallels, dear reader: can you think of any?

Thanks, as always, for reading this.

MTCIDC

CD