Tags

Battle of the Somme, British Expeditionary Force, chemical warfare, Fritz Haber, Gas warfare, Great War, John Singer Sargent, maxim gun, mustard gas, tear gas, The Lord of the Rings, The Siege of Gondor, Tolkien, trench warfare, trenches, Vale of Anduin, WWI, Young Indiana Jones

Welcome, as always, dear readers.

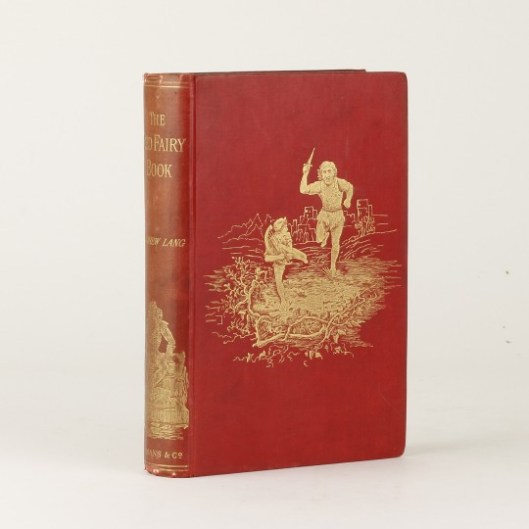

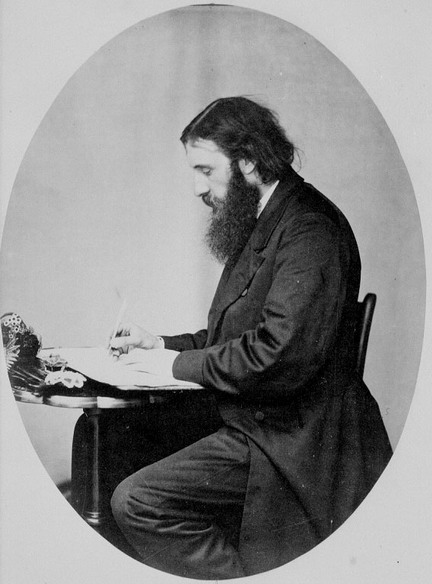

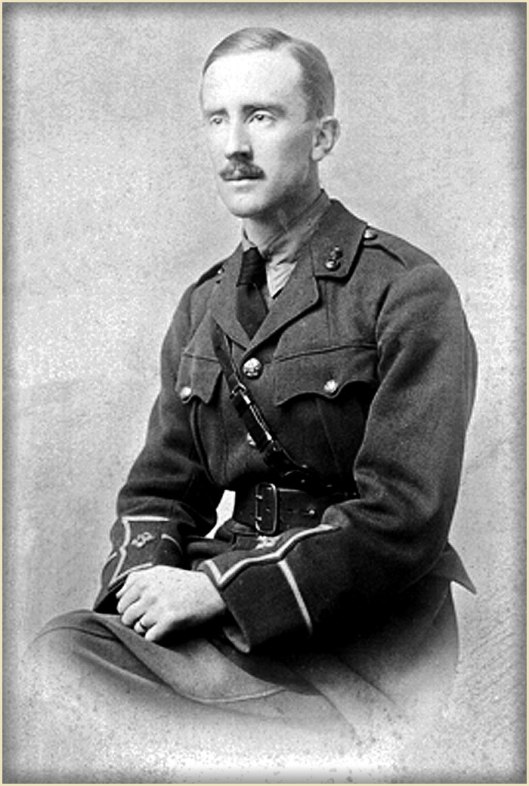

In this, the last year of the centennial of the Great War, we are often reminded not only of that conflict, but also that Second Lieutenant J R R Tolkien took part in it.

By the time he had reached the Front, in July, 1916, the latest round of blood-letting, the infamous Somme, was already in progress.

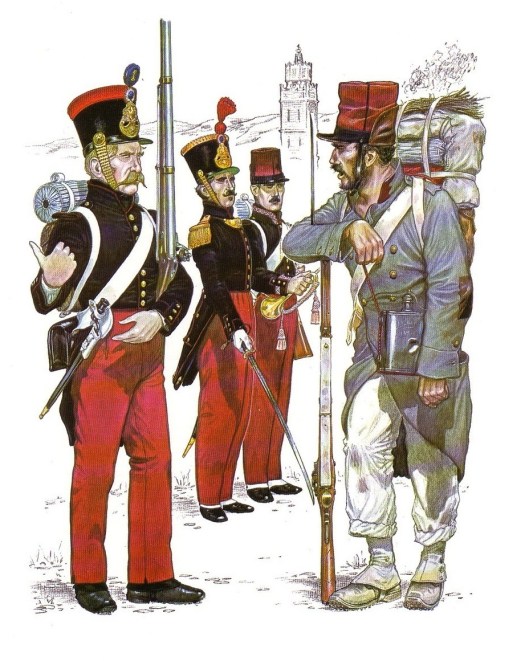

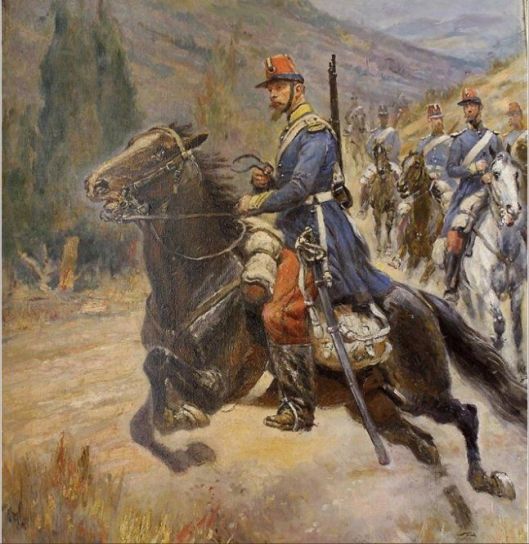

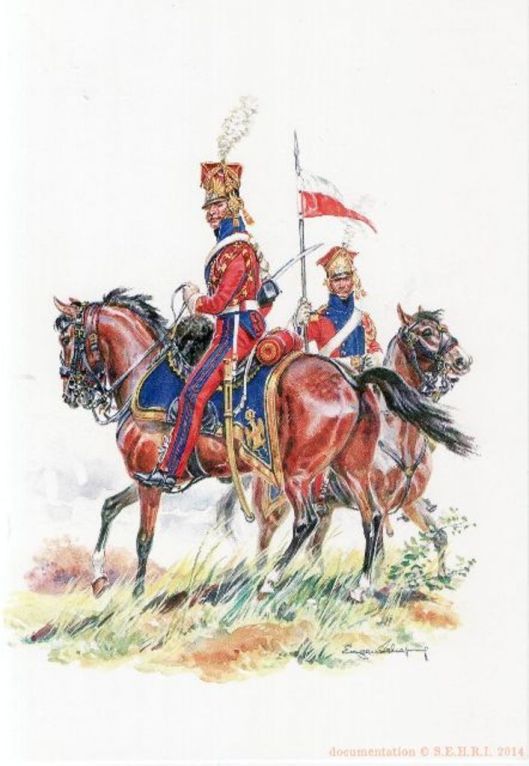

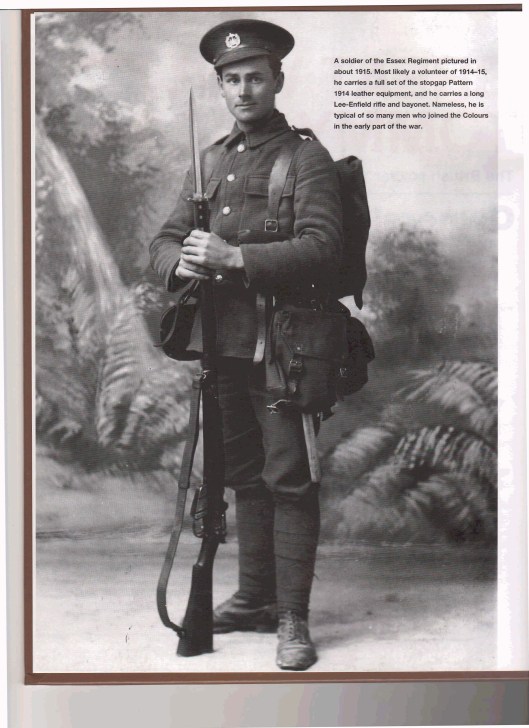

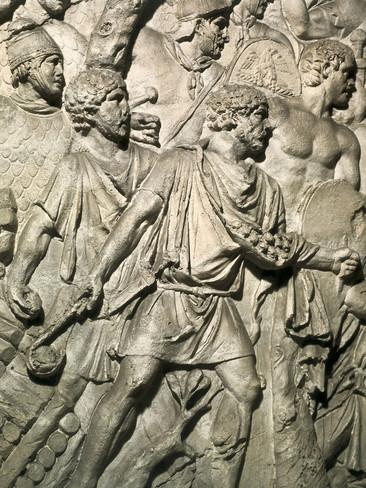

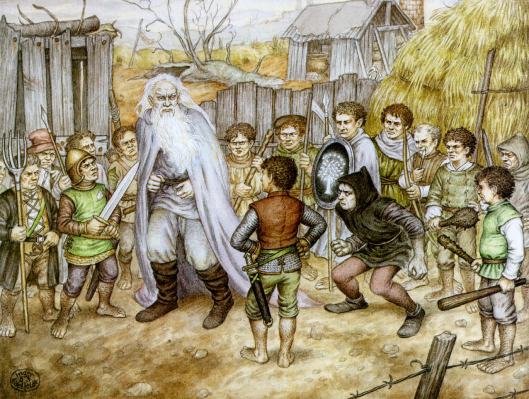

“Blood-letting” is an understatement: on the first day of the battle, 1 July, 1916, there had been nearly 60,000 British casualties and attacks would continue till November. The problems faced were mainly those of 1914. The well-equipped, well-trained professional soldier of the British Expeditionary Force

met the Maxim Gun

and took heavy casualties. These casualties were multiplied by the number and range of German artillery.

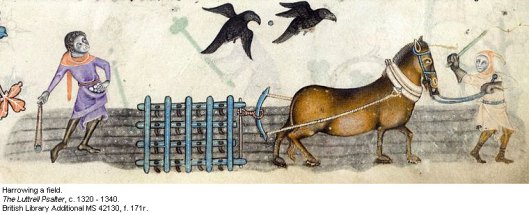

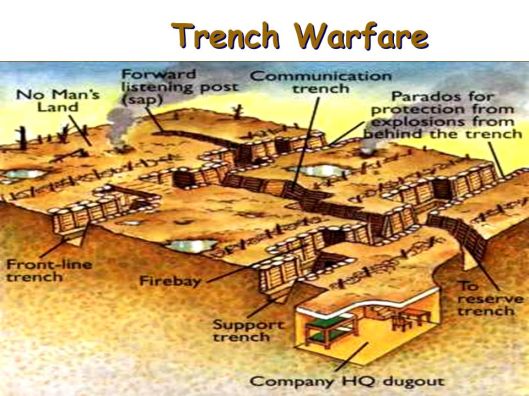

To defend themselves against these modern weapons, soldiers went to ground as soon as they could.

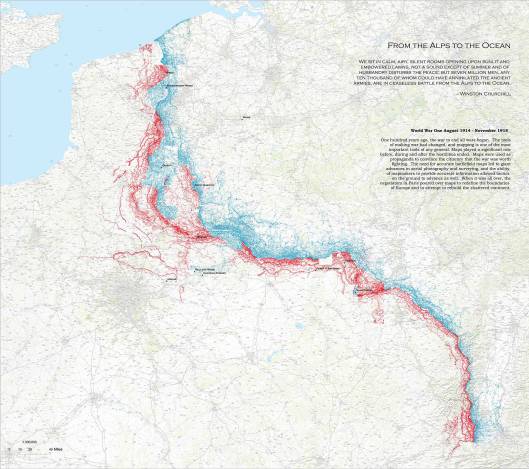

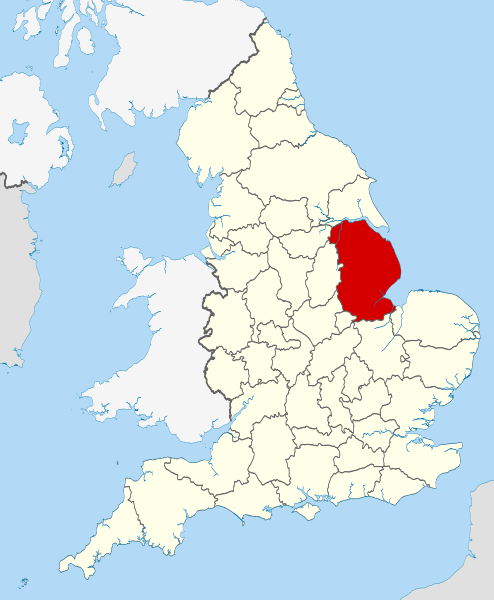

Digging in moved from a simple scrape of the earth into 500 miles (from Switzerland to the North Sea) of often very elaborate earthworks.

Equip these with machine guns

and spread acres of barbed wire in front

and you can think that you’re safe from attack.

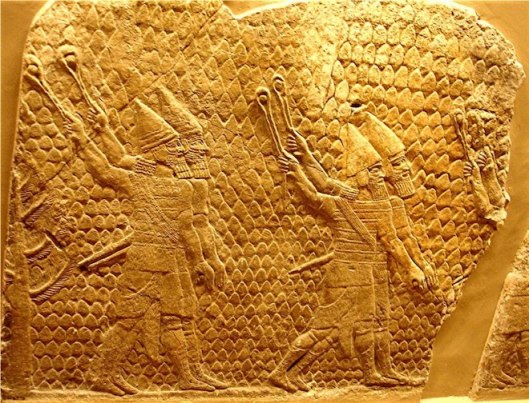

So, the problem then was: how to break through? And this is where the German chemical industry

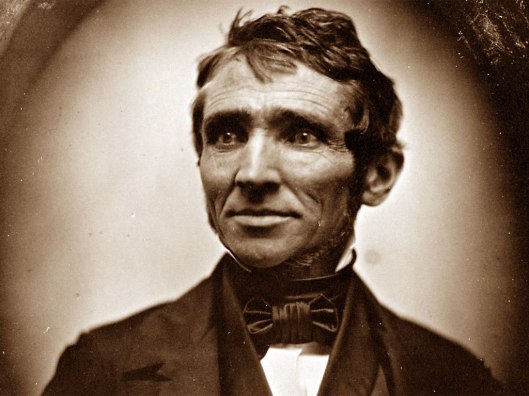

and its brilliant chemist, Fritz Haber,

(who will share the Nobel Prize for chemistry in 1918) came in.

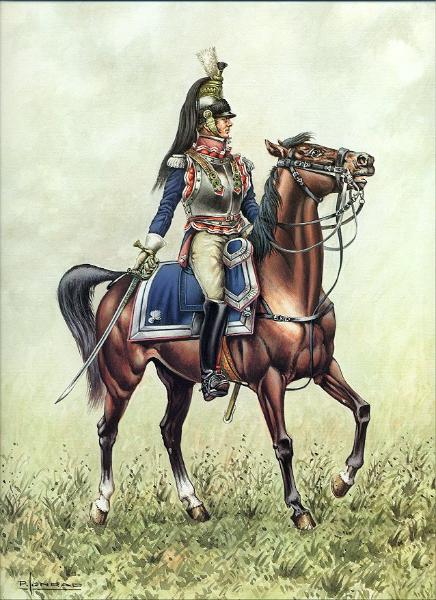

Haber, famous for creating artificial fertilizer—his positive side—was also a captain in the Kaiser’s army (hence the uniform in our illustration), intensely convinced that Germany was justified in waging war on Europe, and began to develop a reply to elaborate fortifications: poison gases—Haber’s dark side.

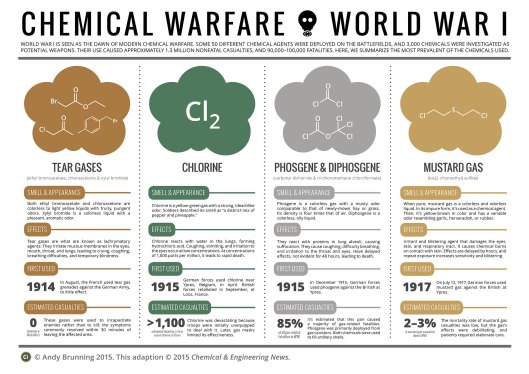

Nearly twenty years before, in 1900, many of the world’s nations, including Germany, had signed an agreement at the Hague that, among other things, they wouldn’t employ such a weapon, but, clearly, the temptation was too great, and not only for Germany. After the first major attack, 22 April, 1915, in which the Germans had killed or driven a large number of French troops from their trenches, the British and French began their own development programs.

Over time, the gases varied as experiments showed scientists and military men what worked and what didn’t. There were simple tear gases, which incapacitated soldiers by blinding them with their own tears and disturbed their breathing, to much deadlier blister agents—but here’s a chart to lay out the effects.

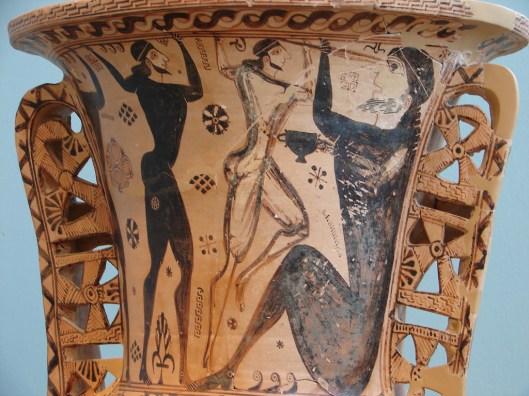

Delivery systems varied. Gas might be released from canisters, allowing the prevailing wind to carry it to the enemy.

The difficulty here was the variability of winds—should the direction change, the releasers of gas might—and sometimes did—find themselves the victims.

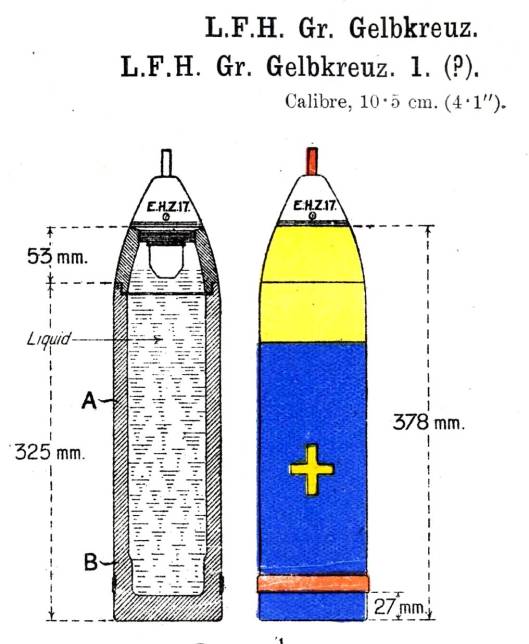

Gas packed into artillery shells was more dependable.

Shells were marked to identify which gas was inside, as in this illustration.

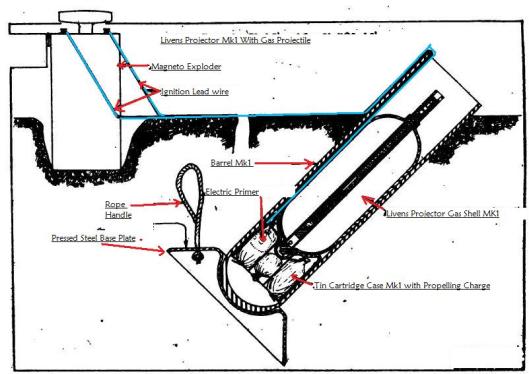

In time, the British developed a method of projecting gas bombs in large numbers with what were called “Livens projectors”.

This simple mechanism could be used in banks to blanket the enemy line with poisonous air.

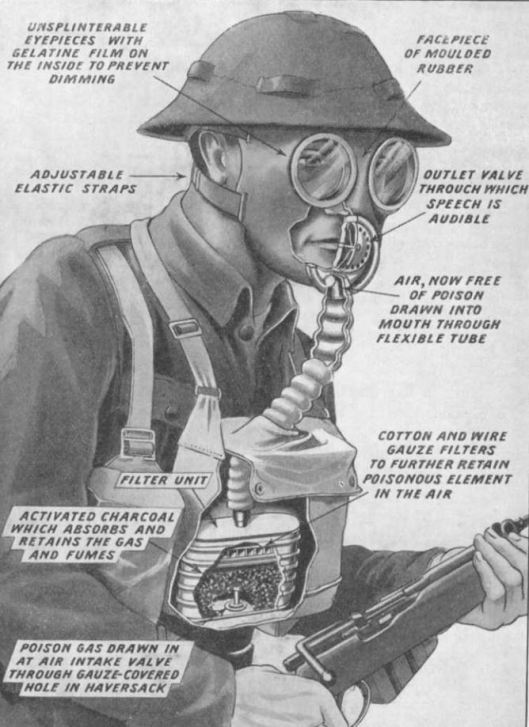

Initially, there had been no defense against this weapon, but, in time, both sides developed gas masks.

And, of course, something had to be done for the hundreds of thousands of horses both depended upon.

Here’s how the later, more efficient ones worked.

They might have prevented suffocation, but they were uncomfortable and, worse, the lenses soon fogged over, making it difficult to see the enemy in their masks advancing through the clouds of gas.

In the television series about young Indiana Jones of some years ago, there was a very graphic depiction of this—and here’s a LINK so that you can see for yourself. (We very much recommend this series, by the way. On the whole, it has many episodes which not only fill in Indie’s past, but are good adventure stories in themselves.)

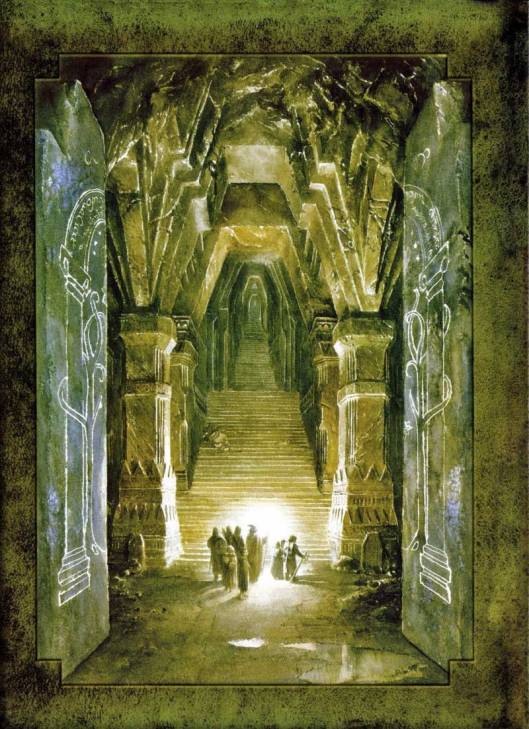

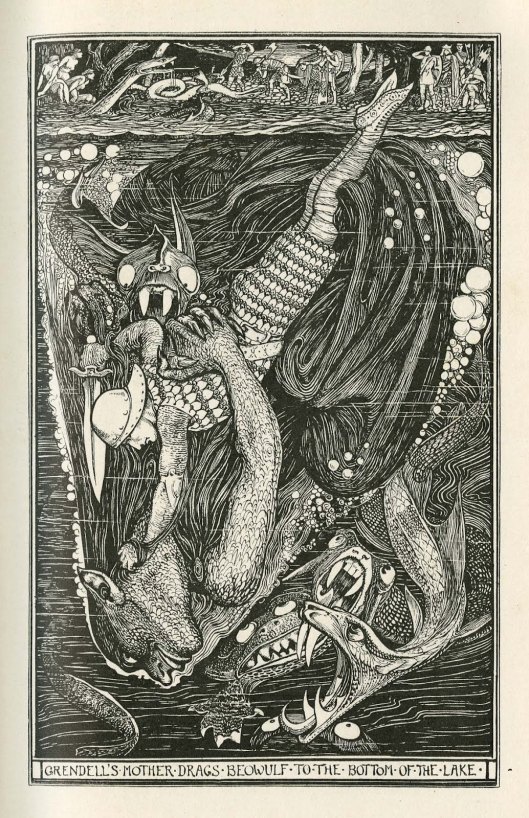

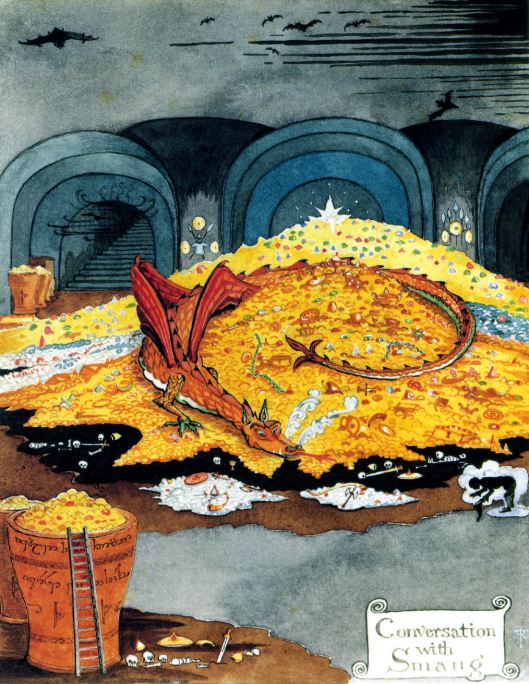

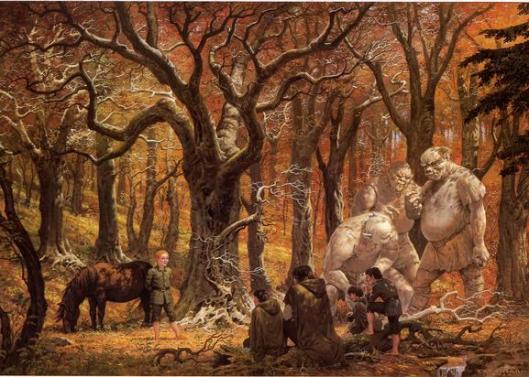

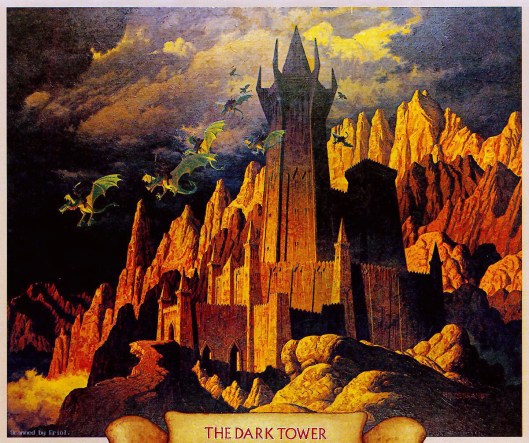

We can imagine, then, what might have been going on in JRRT’s mind when he wrote:

“It was dark and dim all day. From the sunless dawn until evening the heavy shadow had deepened, and all hearts in the City were oppressed. Far above a great cloud streamed slowly westward from the Black Land, devouring light, borne upon a wind of war; but below the air was still and breathless, as if all the Vale of Anduin waited for the onset of a ruinous storm.” (The Return of the King, Book Five, Chapter 4, “The Siege of Gondor”)

Were those orcs approaching, or the Kaiser’s infantry?

Thanks, as ever, for reading.

MTCIDC

CD

ps

The horrific effects of chemical warfare have, to us, never been more powerfully depicted than in John Singer Sargent’s (1856-1925) Gassed (1919), based upon Sargent’s visit to the Western Front in July, 1918.

pps

But, you know us—if we can add a little something more, we always will and, in this case, we want to end not with just this image, horrible and moving as it is, but with something from another of Sargent’s works. Along with being a society painter, he was one of the greatest American watercolorists and has left us a collection of beautiful, atmospheric works from Europe, the US, and the Caribbean. We want to end, then, with these very different clouds–

or how the grain is raised and processed to get to the mills

or how the grain is raised and processed to get to the mills