Tags

Alexander the Great, Alice in Wonderland, Barrow-downs, Barrow-wights, Bayeux Tapestry, Brunhilde, Charlemagne, Cheshire Cat, circlet, Cleopatra VII, diadem, Egypt, Egyptian crowns, Elightenment France, Eowyn, French Revolution, Gondor, Gondorian crown, Greek, Greek coins, Hildebrandts, Imperial Crown of the Holy Roman Empire, Julius Caesar, Lupercalia, Marcus Antonius, Medieval, Napoleon I, Nazgul, Octavian Augustus, Pharoahs, Philip II, Pontifex Maximus, Ptolemy I, Queen Elizabeth I, Queen Elizabeth II, Queen Victoria, Richard Wagner, Rohan, Romans, Tenniel, The Lord of the Rings, Theoden, Tolkien, William Shakespeare, Witch-King of Angmar, wreaths

Welcome, dear readers, as ever.

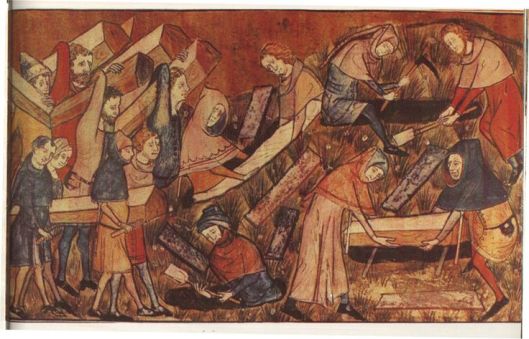

Recently, one of us was lecturing on ancient Egypt, a country of two lands, in fact, Upper and Lower, and each could be represented in the crown worn by the pharaoh.

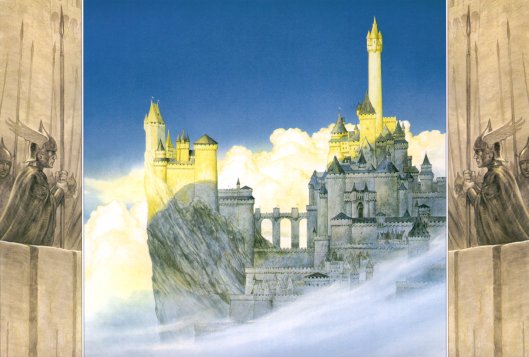

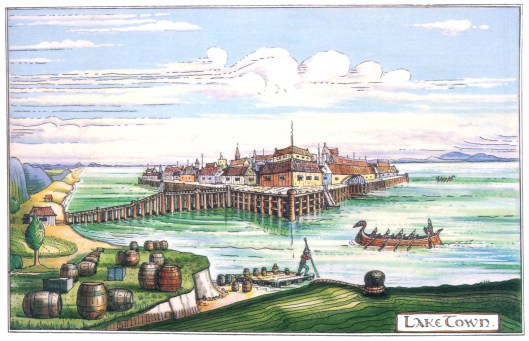

Within in blink, we began to think about JRRT’s illustration of the traditional crown of Gondor,

of which Tolkien says:

“I think that the crown of Gondor (the S. Kingdom) was very tall, like that of Egypt, but with wings attached, not set straight back but at an angle.

The N. Kingdom had only a diadem (III 323). Cf. the difference between the N. and S. kingdoms of Egypt.”

(Letters, letter to Rhona Beare, 10/14/58, 281)

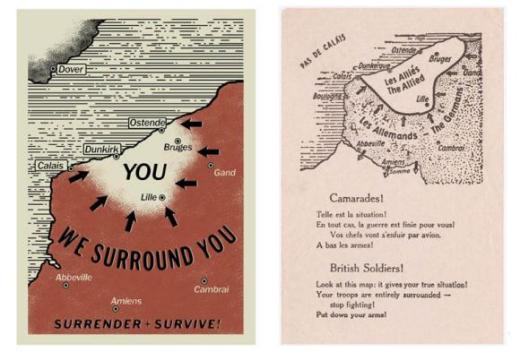

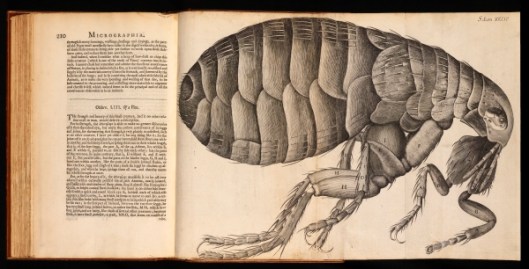

For us, the first crown we believe we ever saw as children was either one in an illustrated fairy tale (here’s a Tenniel illustration from Alice)

or the actual one of Queen Elizabeth II, and that hardly fits JRRT’s idea about the southern crown—or the northern one

or that of her ancestor, Queen Victoria

or that of their distant ancestor, Elizabeth I.

When we think of a “diadem”, however, we are reminded of the earliest western European crowns, which, in contrast to Elizabeth’s, is barely there at all.

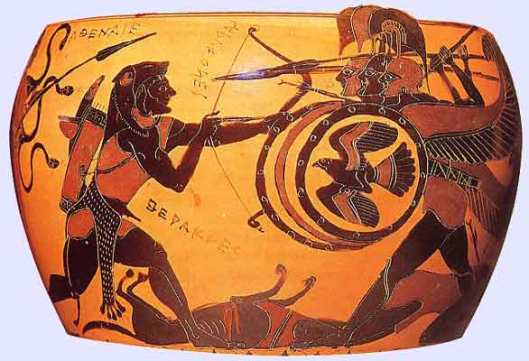

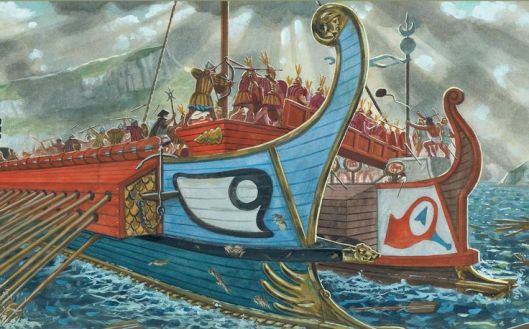

Here is the first type of crown we know of being depicted—it’s that “diadem” in a Greek form, being on a coin of Philip II, King of Macedon and father of Alexander the Great (the reverse—the back side—the front side is called the “obverse”—shows Philip’s Olympic victory horse and Philip’s name in the genitive—possessive—case, “of Philip”—showing not only possession of the horse, but of the victory, of the coin, and, by implication, the right to issue coins).

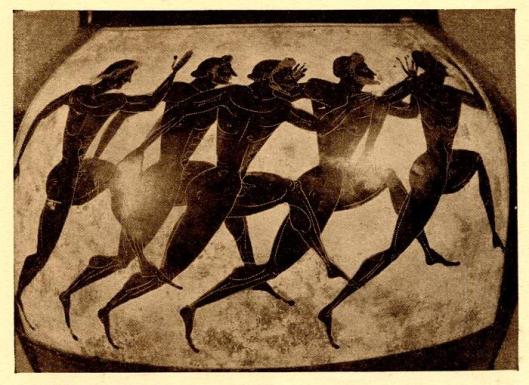

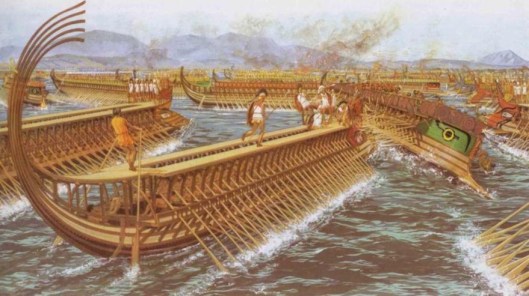

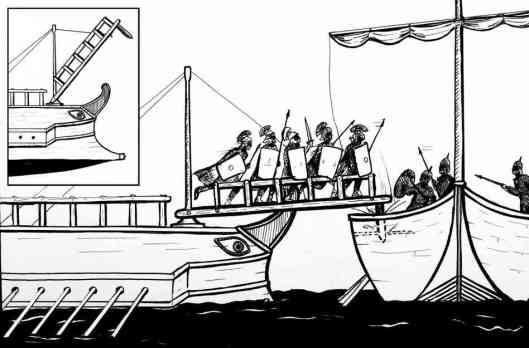

This became a regular pattern, both of coin and of crown for those who followed Philip, and, thinking about Philip’s victory, we can imagine that the original of the crown was based upon the wreath athletic game victors wore.

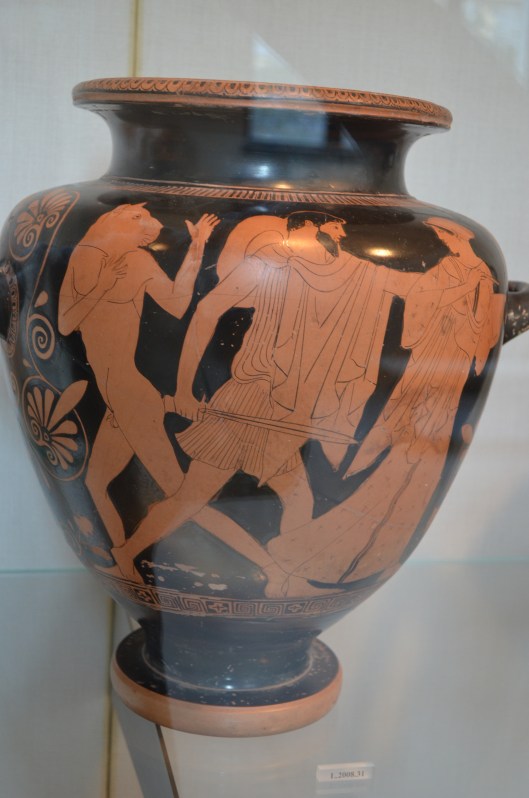

And coins like Philip’s set the pattern for classical coins—and crowns—for centuries. Here’s the crown pattern on the head of Ptolemy I, one of Alexander’s generals.

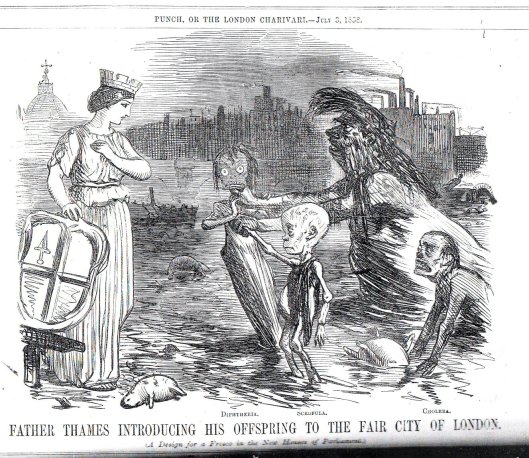

At Alexander’s death, Ptolemy seized Egypt, making it a family possession for the next nearly three hundred years, all the way down to his greatgreatgreat etc granddaughter Cleopatra VII.

The pattern was not confined to Greece or Egypt, however—Julius Caesar wore something similar—

although, unlike Ptolemy and other such rulers, Caesar might have hoped to muddy people’s perceptions of what such a thing symbolized and what position (dictator for life) he’d forced the Senate to give him. Rome had hated monarchs, after all, since they’d kicked out their last king 450 years before.

(And see Act I, Sc.2 of Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar in which, at the festival of the Lupercalia, Marcus Antonius publically offers him a crown and Caesar rejects it, much to the loud delight of the mob.)

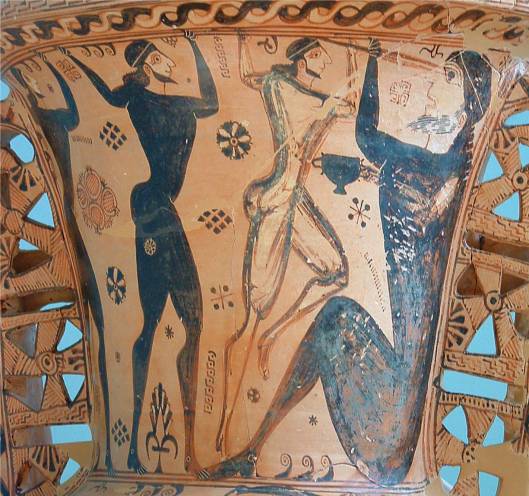

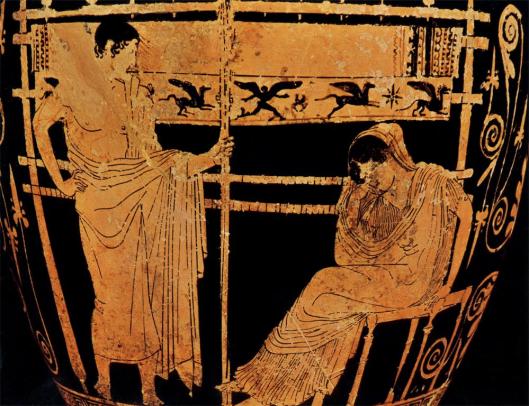

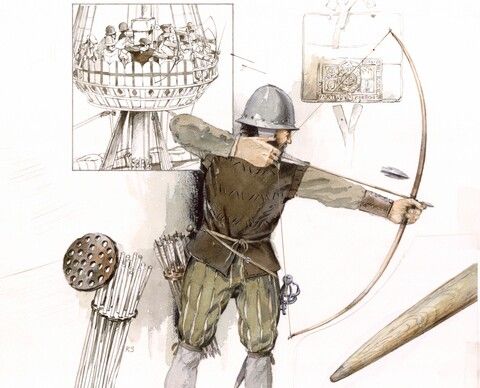

In the Greco-Roman world, wreaths had many purposes: besides Greek kings and winners at games, people at parties and weddings and other festive occasions wore them, as well as celebrants at religious rites.

Perhaps Caesar hoped that, appearing in one, he might appear less like a Hellenistic king and more like anything from an Olympic victor or party-goer to a priest (he was Pontifex Maximus, head of religion in Rome, so there was a certain credibility to the latter).

Malicious people in Rome also suggested another reason for the wreath: Caesar was sensitive about his thinning hair.

Caesar’s grandnephew and successor, Octavian/Augustus, continued the tradition,

as did following emperors for several centuries—and even Charlemagne, hundreds of years after the last western emperor, revived it.

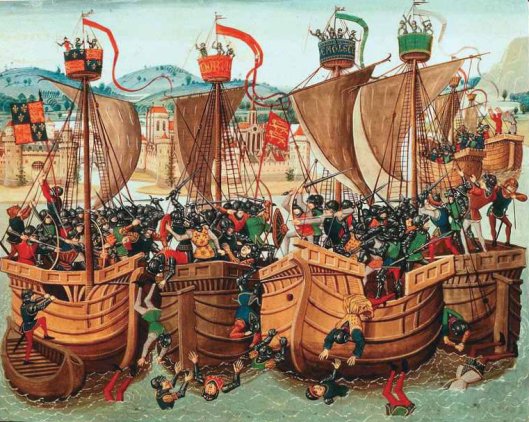

At some point, just after Charlemagne’s time or thereabout (c1000ad), a new pattern appeared, which you can see in the famous “Imperial Crown of the Holy Roman Empire”.

Instead of a wreath, this was a built-up circlet, with lots of “bits and bobs” on top.

This newer look persisted in various more or less complicated forms in the west for centuries

and seems to underlie the crowns seen in more recent times (often with what appears to be a red velvet balloon in the middle).

There is a throwback, however: Napoleon I. He had grown up in Enlightenment France, in a world which idealized classical learning and art, and so, when he made himself emperor in 1804, his model wasn’t medieval and Germanic, but Augustine.

This doesn’t mean that he wasn’t aware of that other model and he would have used it—the so-called “crown of Charlemagne”–at his self-coronation

had it not suffered the fate of many medieval treasures and been destroyed during the French Revolution (the famous Bayeux Tapestry was almost converted to wagon covers by revolutionaries). In fact, a “crown of Charlemagne” did turn up for the ceremony—“recreated” by a clever Paris jeweler.

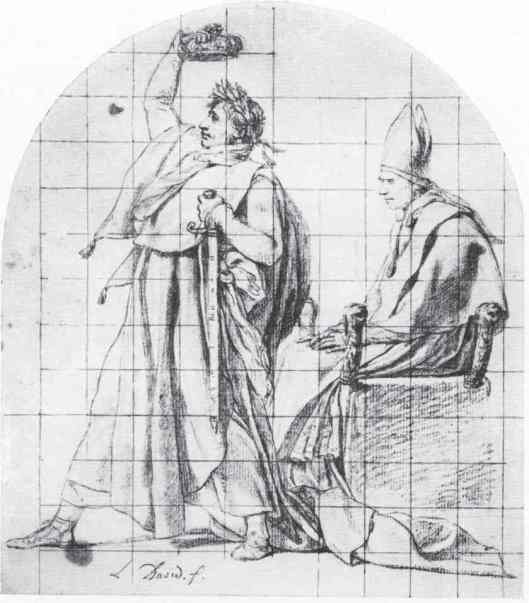

[A footnote about the coronation. In the painter David’s sketches for it, he shows the pope (Pius VII) with his hands in his lap.

Napoleon saw the drawing and said to David that the pope should be blessing the occasion—after all, that’s why Napoleon had dragged him all the way from Rome. David redid his sketch, of course!]

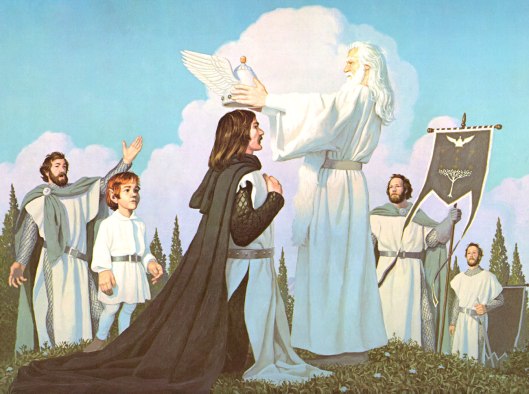

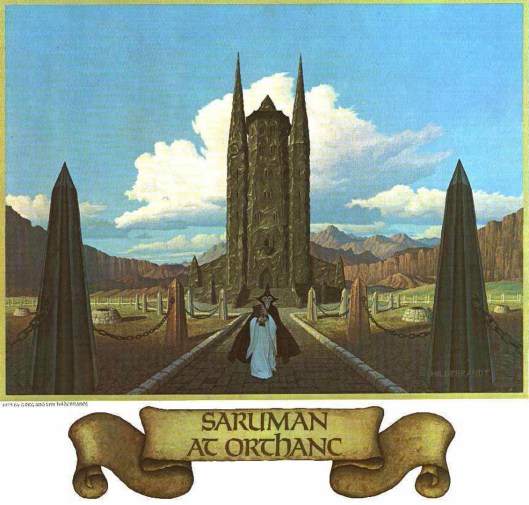

Beyond the Crowns of Gondor, most of the crowns seen in The Lord of the Rings are described as “circlets”—

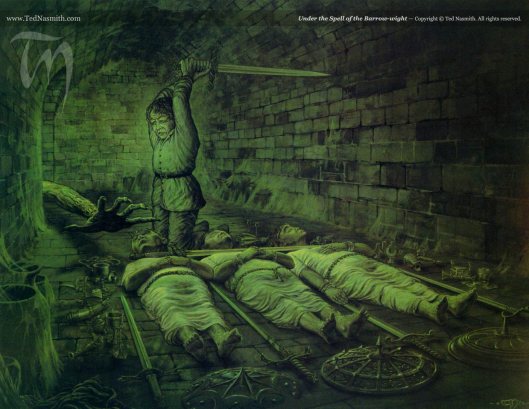

- Sam, Merry, and Pippin, laid out in the barrow:

“About them lay many treasures of gold maybe, though in that light they looked cold and unlovely. On their heads were circlets, gold chains were about their waists, and on their fingers were many rings.”(The Fellowship of the Ring, Book One, Chapter 8, “Fog on the Barrow-Downs”)

- Theoden:

“Upon it sat a man so bent with age that he seemed almost a dwarf; but his white hair was long and thick and fell in great braids from beneath a thin golden circlet set upon his brow.” (The Two Towers, Book Three, Chapter 6, “The King of the Golden Hall”)

But there is one which, well, looking at the various illustrations of its wearer, reminds us of Alice’s comment upon the Cheshire Cat:

“Well! I’ve often seen a cat without a grin…but a grin without a cat! It’s the most curious thing I ever saw in my life!” (Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, Chapter 6, “Pig and Pepper”)

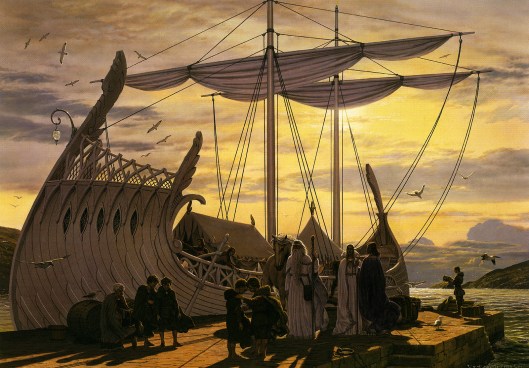

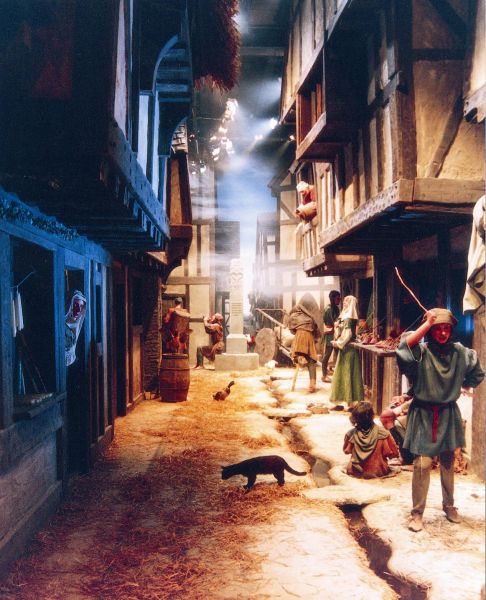

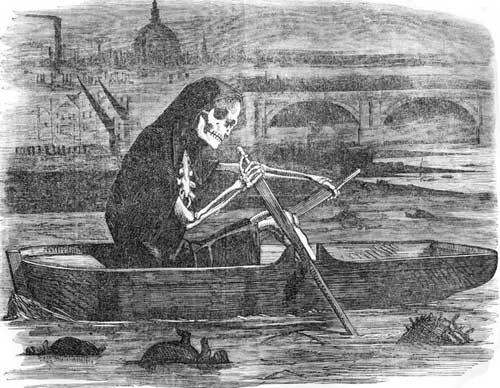

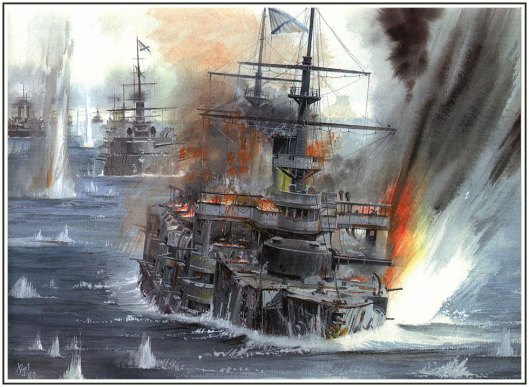

On the Fields of the Pelennor, a “great shadow descended like a falling cloud. And behold! It was a winged creature.”

This might be bad enough, but:

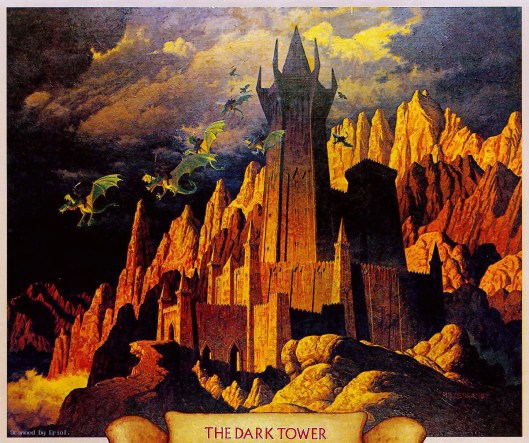

“Upon it sat a shape, black-mantled, huge and threatening. A crown of steel he bore, but between rim and robe naught was there to see, save only a deadly gleam of eyes: the Lord of the Nazgul.” (The Return of the King, Book Five, Chapter 6, “The Battle of the Pelennor Fields”)

We are aware of at least half-a-dozen professional renderings of this scene (and we plan to discuss them all in a future post), but it seems to us that those eyes, seeming to float in space, make it extremely difficult to illustrate it, no matter what crown—simply described as “steel”—he’s wearing. And that brings us back to our original crown. As JRRT described it:

“It was shaped like the helms of the Guards of the Citadel, save that it was loftier, and it was all white, and the wings at either side were wrought of pearl and silver in the likeness of the wings of a sea-bird, for it was the emblem of kings who came over the Sea; and seven gems of adamant were set in the circlet, and upon its summit was set a single jewel the light of which went up like a flame.” (The Return of the King, Book Six, Chapter 5, “The Steward and the King”)

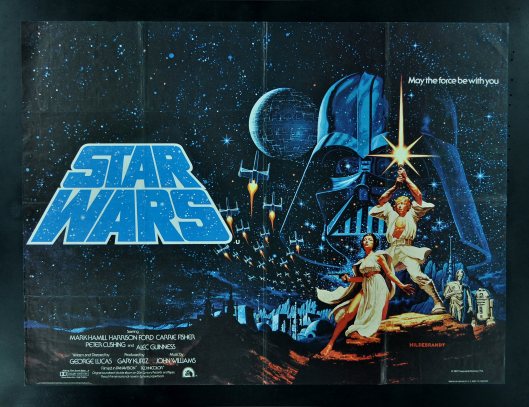

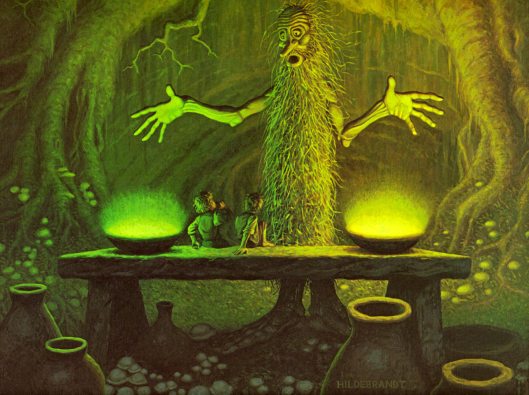

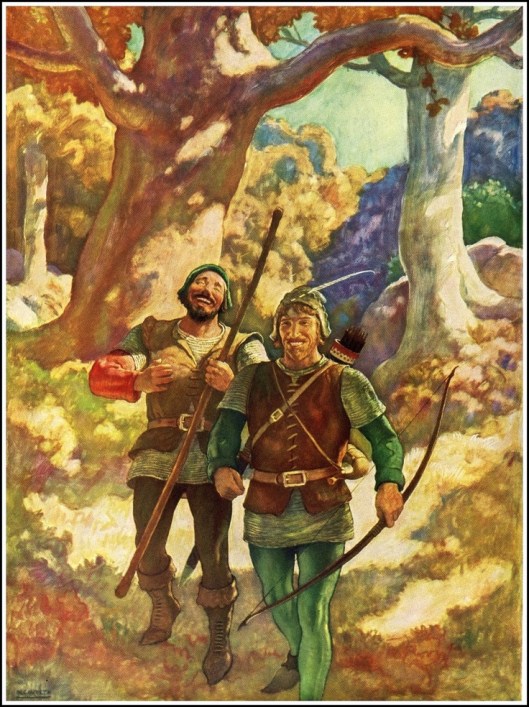

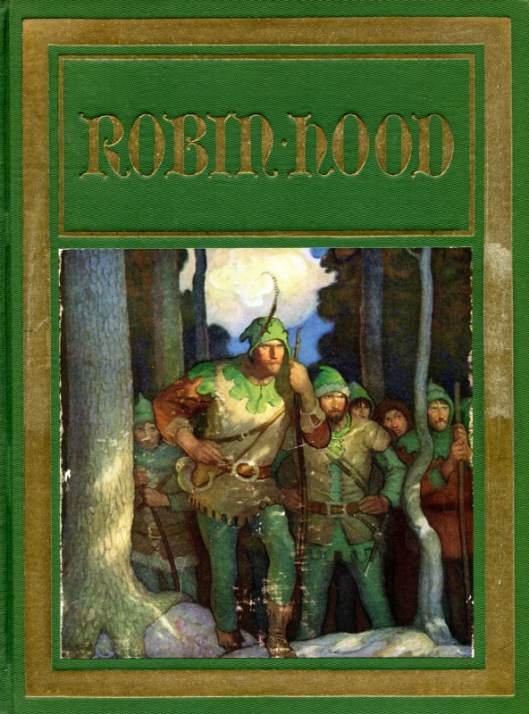

If his drawing (seen at the beginning of this post) is what he had in mind, then the only professional illustration we’ve seen of it, by the Hildebrandts, is only an approximation.

And, in fact, reminds us all-too-easily of Brunhilde, the Walkuere, from Wagner’s operas.

If illustrators as good as the Hildebrandts struggle, this must be a tough one. The designers of the P. Jackson films are even farther away from the original, as so often.

Here, however, we have some sympathy! Somehow the medieval world of Middle-earth can not easily assimilate an Egyptian artifact. And so, we suspect that they thought “circlet” and “wings” and left it there. What do you think, readers? How do you imagine the crown?

Thanks, as ever, for reading.

MTCIDC

CD