Tags

Calendars, Christopher Tolkien, Chronology, David Drake, Drafts, hobbit measurement, Moon Phases, Raj Whitehall, SM Stirling, The General, The Hobbit, The Lord of the Rings, The Stairs of Cirith Ungol, Tolkien

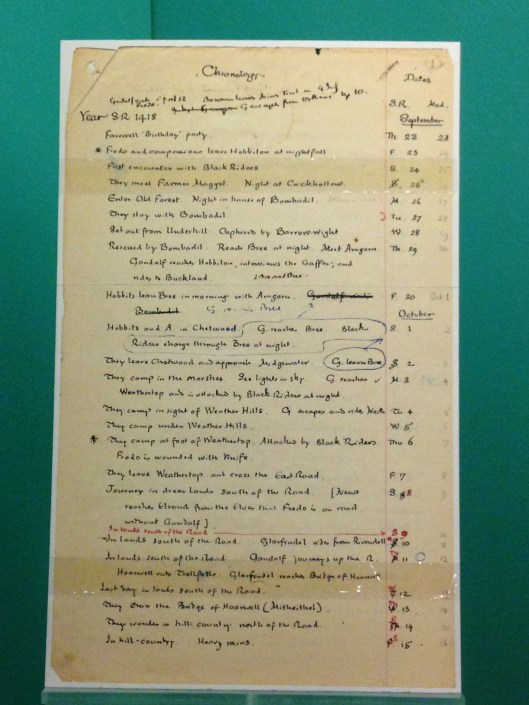

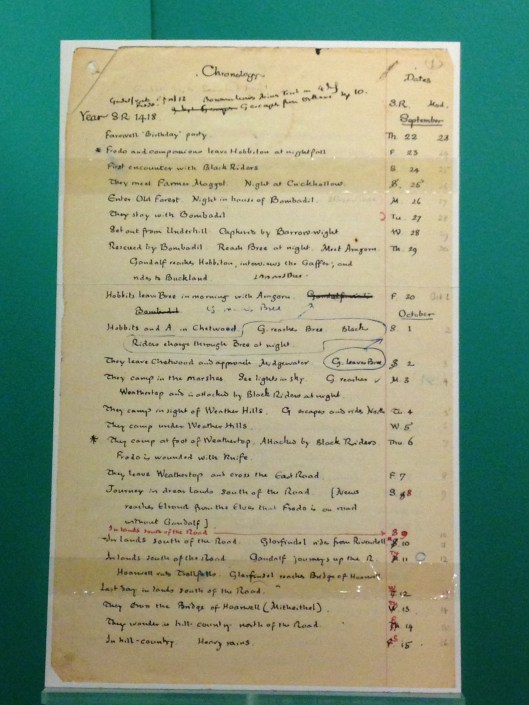

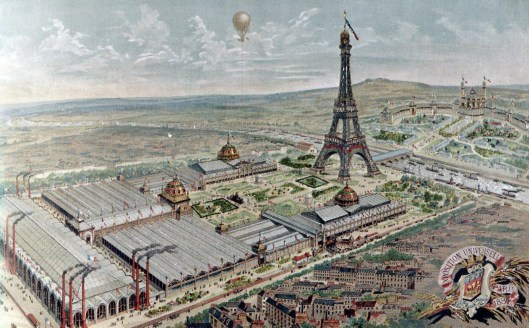

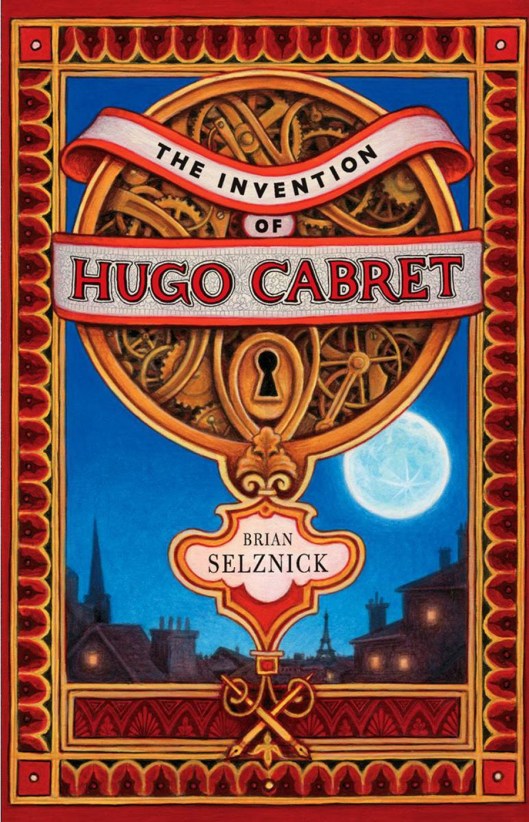

Once upon a time, dear readers (and welcome, as always), this series began with this:

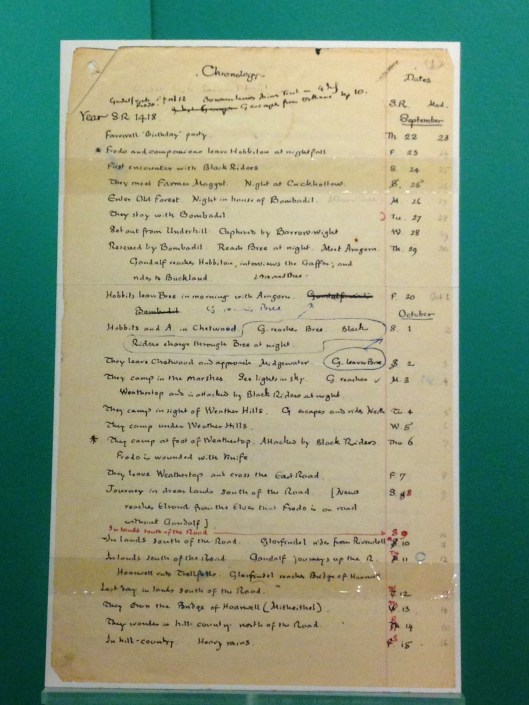

As you can see, it’s a reproduction of the first page of a draft of JRRT’s The Lord of the Rings chronology, which we found in a display case in Reading Adventureland at the marvelous Strong National Museum of Play, in Rochester, NY (the original is in the Tolkien papers at Marquette University).

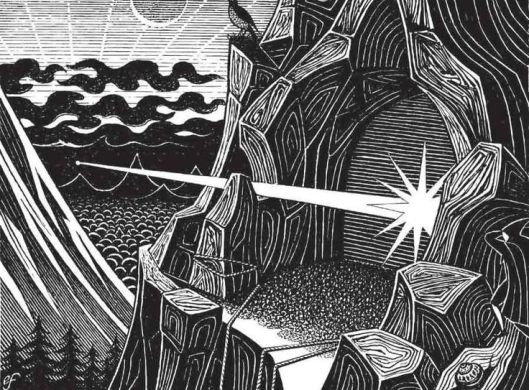

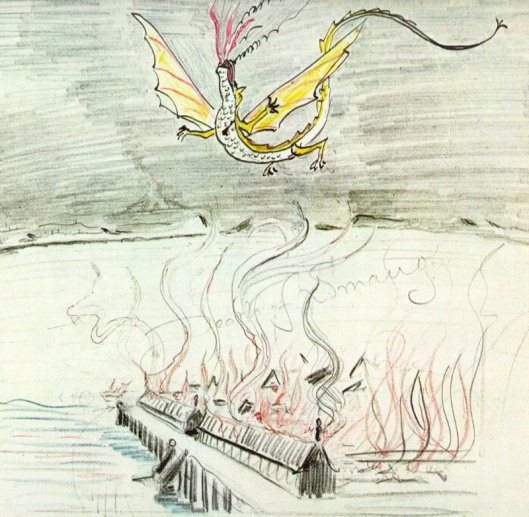

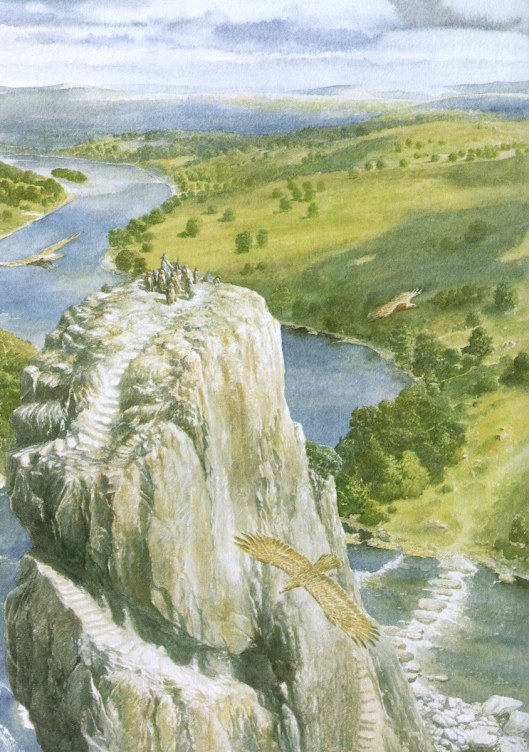

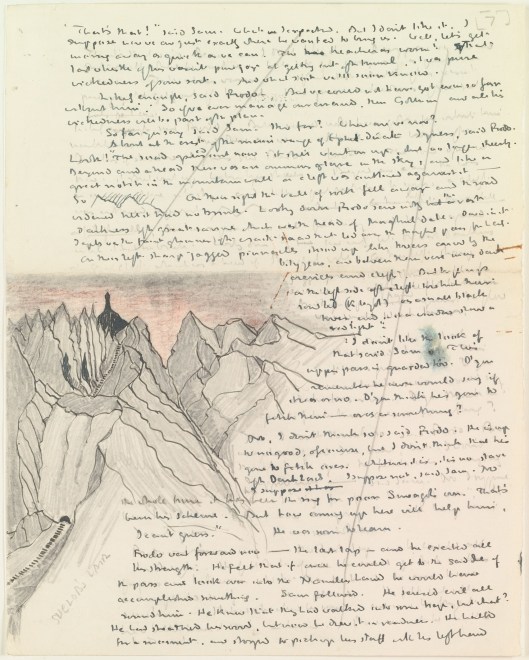

We had seen the eventual complete version of this long ago in Appendix B of The Lord of the Rings, in the section entitled “The Great Years”, but, as with everything original, there’s a special thrill to seeing something much closer to the author than the printed page–like this, a leaf from a draft of what would become The Two Towers, Book Four, Chapter 8, “The Stairs of Cirith Ungol”, illustrated by Tolkien. If you compare it with the final text, it’s very interesting to see all of the kinds of changes JRRT made between it and that which we now read.

(We found this on a site called Biblioklept. As this means “book thief”, we were a little hesitant, at first, but it turned out to be a very interesting place—here’s a LINK to it so that you can see for yourself.)

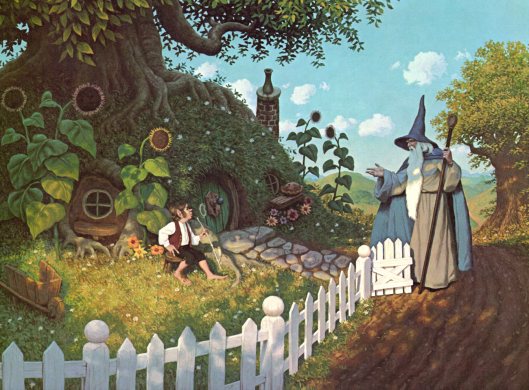

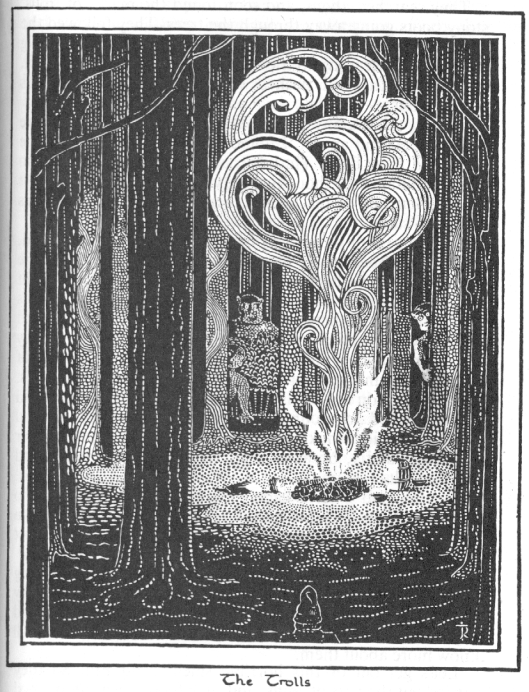

The Hobbit (about which we wrote in parts 1 and 2 of this little series) was quite simple in its chronology. It’s all of a piece, the narrative being focused solely on Bilbo and the dwarves until Smaug flies off to devastate Lake-town (Chapter 14, “Fire and Water”). Even Gandalf’s disappearance in Chapter 7 (“Queer Lodgings”) is never really gone into. The opposite is true in The Lord of the Rings. In the opening chapters of Book One alone, Gandalf appears, Bilbo disappears, years pass and Gandalf reappears and disappears, and it’s only in Book Two that both reappear and we are told by Gandalf what happened between his last disappearance and his present reappearance (“The Council of Elrond”), even though some of what happened to him was occurring at the same time as Frodo’s packing up and leaving the Shire. Here’s a useful chronology from something called “scifi.stackexchange.com” (and here’s a LINK to it).

It’s not surprising, then, that JRRT needed to make very careful notes of who went where and when.

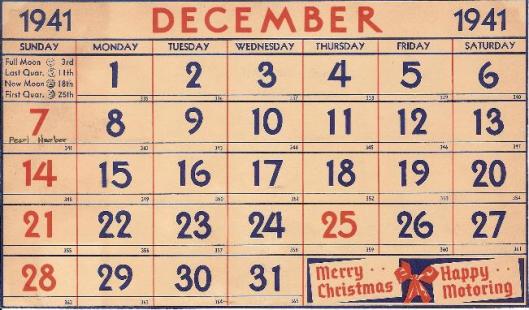

This didn’t always work out, however, as has been pointed out more than once, in the matter of phases of the moon. This is a complicated story (here’s a LINK to help), but, basically, JRRT, as meticulous as he always was, based the moon phases on a calendar from 1941-2

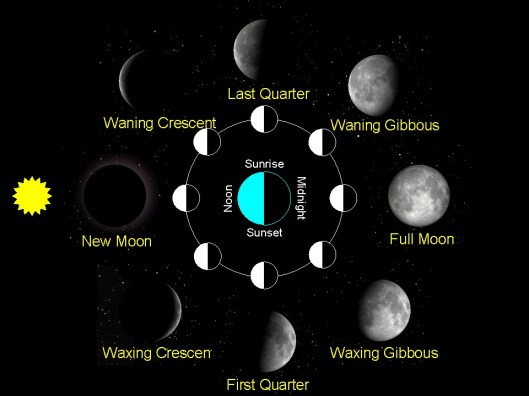

and mistook the marker for “new moon” to mean “the second day of the new moon”, which would have allowed for just the faintest of crescents in the sky, rather than the astronomical definition, “the full dark of the moon”.

Here’s a moon phase chart to help.

We know from a note in Christopher Tolkien’s The Treason of Isengard that JRRT was working from such a calendar (or almanac) because:

“Either while the making of Time-scheme I was in progress or at some later point my father wrote at the head of the first page of it: Moons are after 1941-2 + 6 days. (p. 369—if you happen to consult the Tolkien Gateway: User: Gamling/Hobbitdates on the subject, you will be puzzled at its footnote 2, which cites this volume, and, within it, “The Great River”, note 23, as note 23 says nothing about this)

For us, to focus upon such a detail is to miss the bigger point, however, which was, in fact, encapsulated in W. H. Auden’s review of The Fellowship of the Ring

in 1954:

”Of any imaginary world the reader demands that it seem real, and the standard of realism demanded today is much stricter than in the time, say, of Malory. Mr. Tolkien is fortunate in possessing an amazing gift for naming and a wonderfully exact eye for description; by the time one has finished his book one knows the histories of Hobbits, Elves, Dwarves and the landscape they inhabit as well as one knows one’s own childhood.” (The New York Times, October 31, 1954)

Where does such sense of reality come from?

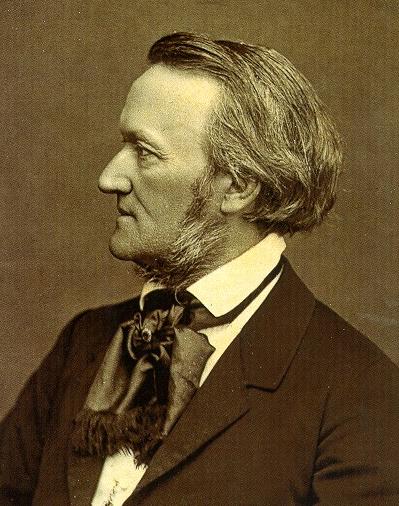

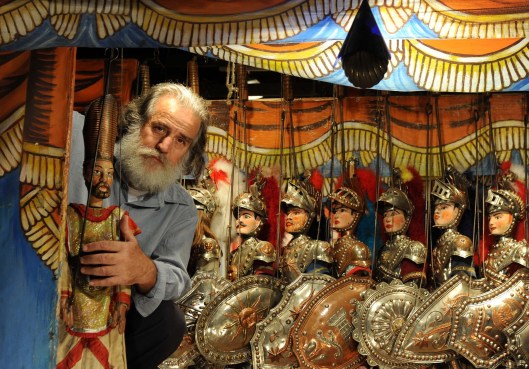

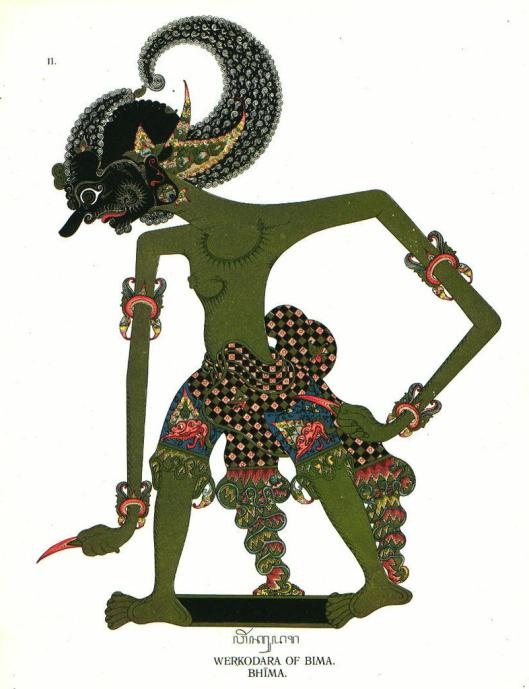

We once read that, before science-fiction authors SM Stirling

and David Drake

began their 5-volume series of the adventures of Raj Whitehall, The General, in 1991 (see LINK—and here’s the first volume book cover),

they created a many-page description of the world, Bellevue, upon which those adventures are set. We thought that that was a great idea and it certainly made Bellevue and all of its events more believable and the narrative more engrossing.

On a much more massive scale, there are the 13 volumes of Christopher Tolkien’s

publication of his father’s papers and his own notes (this is obviously just a few of the books).

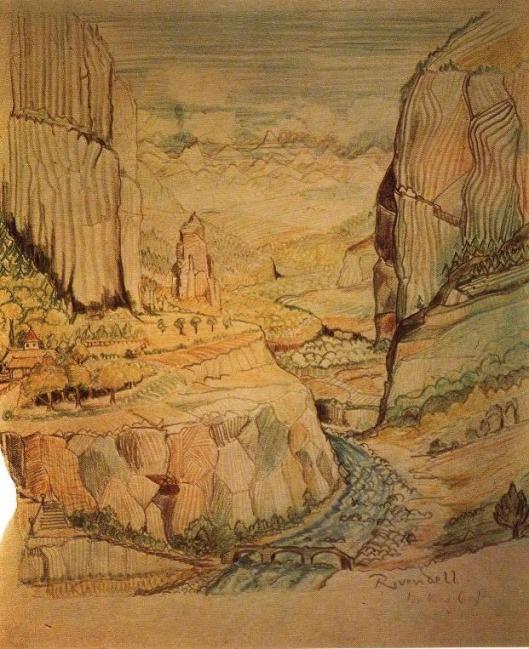

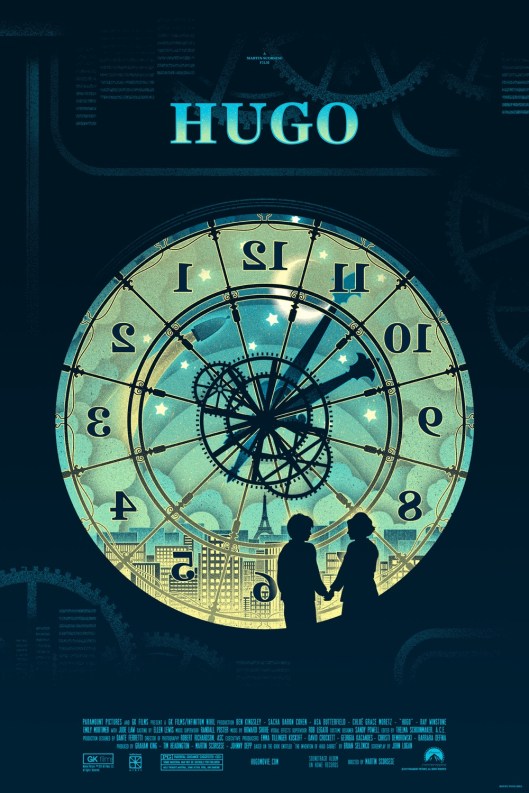

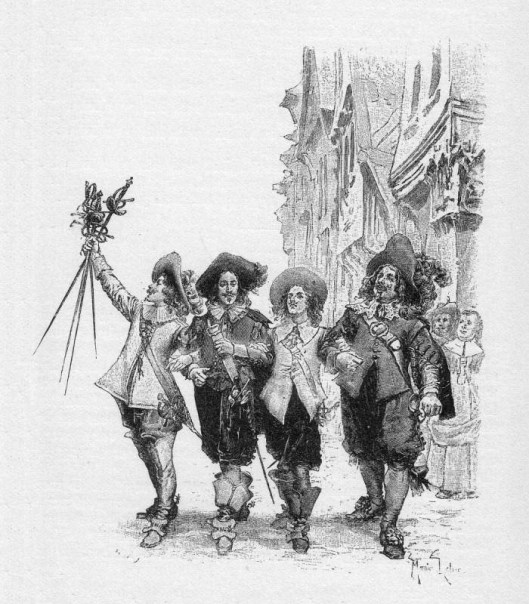

For us, however, there is a small, but equally revealing image of what lies behind JRRT’s work.

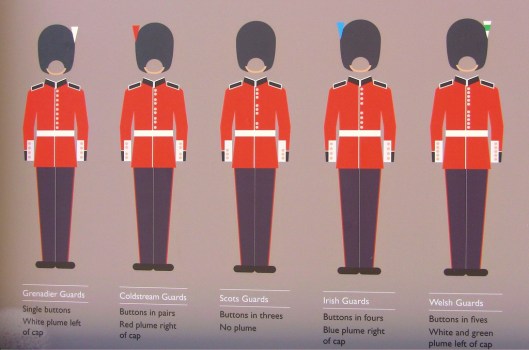

This is another item from that display case at the Strong Museum (and the original is also from the Tolkien collection at Marquette). As you can see, it’s a menu card, for a formal dinner, and we don’t know whether an always-paper-hungry Tolkien tucked it into a coat pocket to use at a later date, or whether it was a very boring dinner and he whiled away the time till the “cheese straws” by creating a neat little measurement system based upon hobbit physiognomy (we hope it was the latter).

What particularly catches our attention is the detail that “6 toes = 1 foot” (odd—do hobbits have six toes, like certain cats?)—but added to that, in a gloss to the right, is the translation into English measure that this hobbit “foot” equals 9 inches. The standard English measure of a foot is 12 inches, but in the days before the English conquest of Wales in the 13th century, (under Edward I, 1239-1307), something called the “Venedotian Code” provided the measurement system in northern Wales, and, in that system, the foot was 9 inches—could it be that JRRT thought of the hobbits as Welsh?

Thanks, as ever, for reading.

MTCIDC

CD