Tags

Battle of Culloden, Beethoven, celebrations, Crowning of Aragorn, endings, George Lucas, Haendel, Joshua, Judas Maccabaeus, oratorio, Return of the Jedi, Star Wars, The Empire Strikes Back, The Field of Cormallen, the Force, The Grey Havens, The Last Jedi, The Lord of the Rings, The Phantom Menace, The Red Book of Westmarch, The Return of the King, The Scouring of the Shire, Tolkien

Welcome, as ever, dear readers.

With Star Wars IX to appear in mid-December, completing the series, we’ve been going back through all of the previous episodes, from I (The Phantom Menace)

through VIII (The Last Jedi).

It’s a remarkable achievement and we’re very grateful to George Lucas,

for bringing it so far, even if his strong sense of the story seems to have been abandoned after VI (Return of the Jedi).

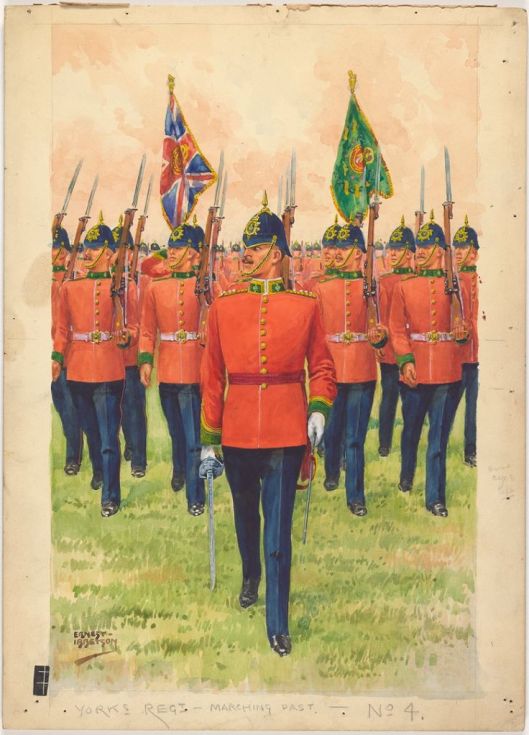

Because there are now so many films (including all of the offshoots, like the animated features, as well as Rogue One and Solo), it’s sometimes hard to remember that, once upon a time, there was only Star Wars (only later A New Hope), with its triumphant conclusion—mass formations of troops, Princess Leia in an actual princess outfit, and medals all around.

The next film—now V (The Empire Strikes Back) had a much less secure ending, with Darth Vader and the Emperor appearing to win and Han Solo a prisoner, on his way to Jaba the Hutt,

but VI (The Return of the Jedi) is once more triumphant, both in its original ending, on the forest moon of Endor,

and in the later revised version, where we see galaxy-wide celebrations.

Among the other films, we’ve seen another celebration, on Naboo, at the end of I (The Phantom Menace),

a secret marriage in II (Attack of the Clones),

and a complex web of plot, including the construction of the Death Star, the separation of the babies—Leia to Alderan, Luke to Tatooine—and the funeral of Padme in III (The Revenge of the Sith).

VII (The Force Awakens) had a mysterious ending: Rey having gone to what appears the far end of the galaxy to find—

while VIII (The Last Jedi) seemed vaguely hopeful, with an unnamed stable boy showing signs of having the Force within him, as Anakin did in I.

With such a build-up, we’ve been wondering how IX (The Rise of Skywalker) will end. As it’s supposedly the final episode, we assume that it will not conclude up in the air, like V, but will it have a mass celebration, like I, IV, and VI?

Or will it, like III, have multiple endings? As we’ve thought about it, you could really see that as the case with The Lord of the Rings.

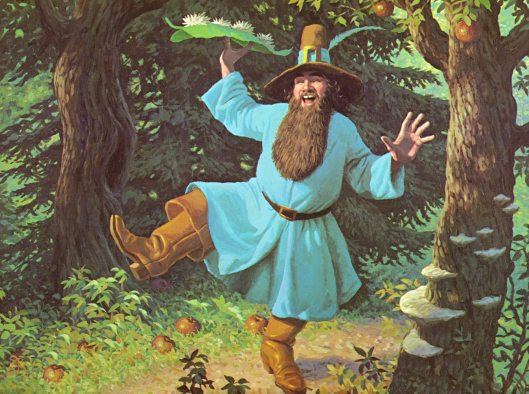

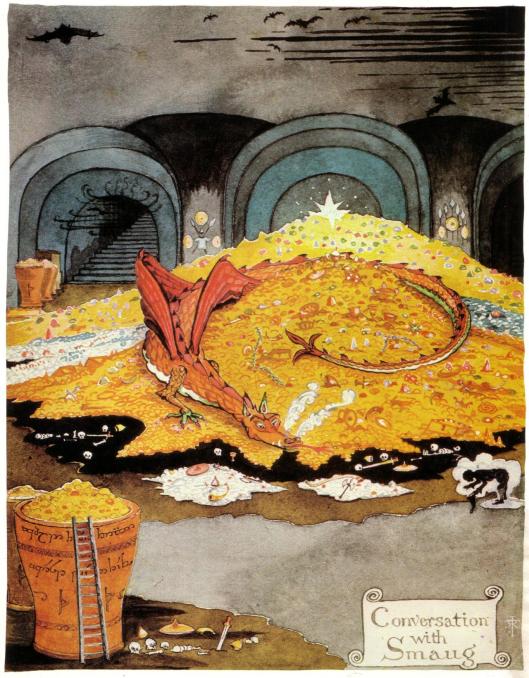

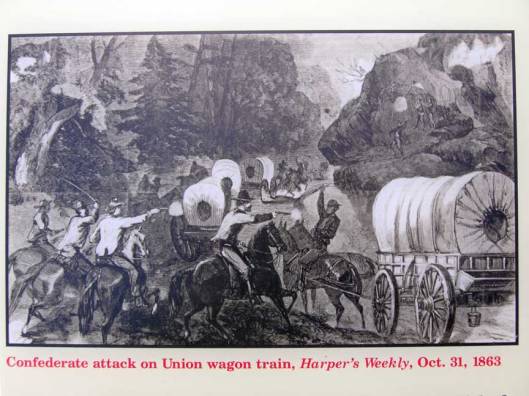

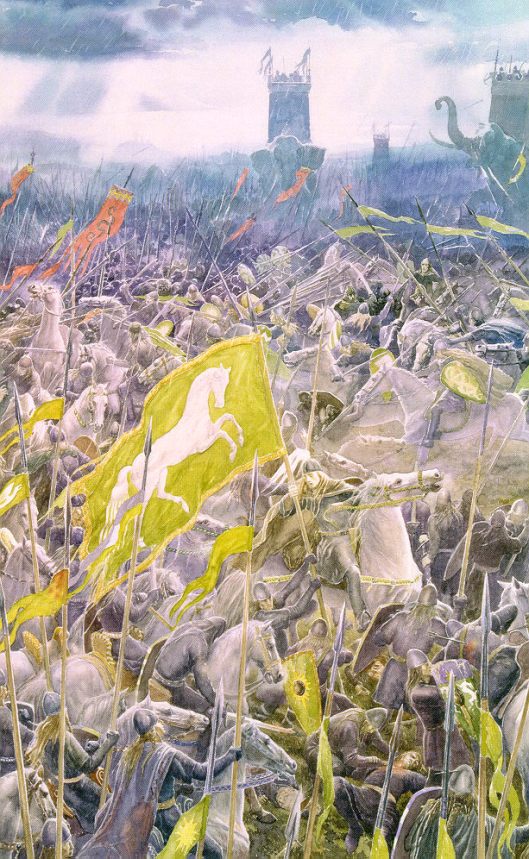

First, like I, IV, and VI, there are celebrations: of Frodo and Sam at the field of Cormallen, in The Return of the King, Book Six, Chapter 4, “The Field of Cormallen”.

Then, in Chapter 5, “The Steward and the King”, we have the crowning of Aragorn

followed by the wedding of Arwen and Aragorn.

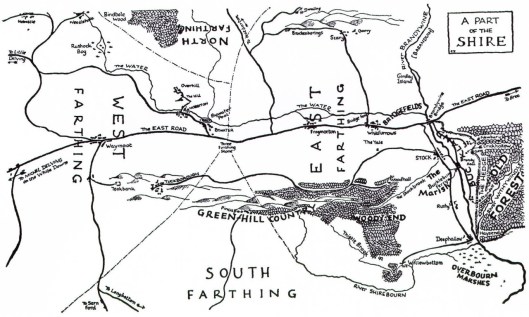

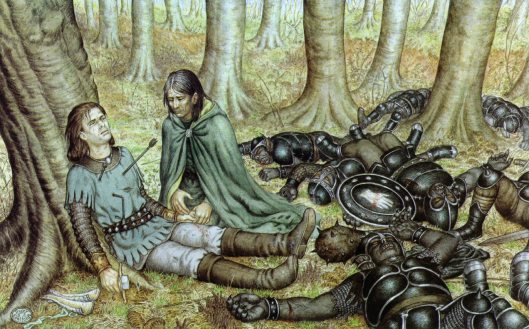

After that, we have the return of the hobbits to the Shire and the defeat and death of Saruman in Chapter 8, “The Scouring of the Shire”. The Shire has been badly damaged by Saruman and his henchmen, however, so that, although they are gone, the healing will take many years.

And the story doesn’t conclude there. Only a little time goes by and then there is another ending: the trip to the Grey Havens and beyond in Chapter 9, “The Grey Havens”.

And then the story finally ends—or does it? We’ve seen in Star Wars VIII, when the stable boy seems to use the Force, though only for a moment,

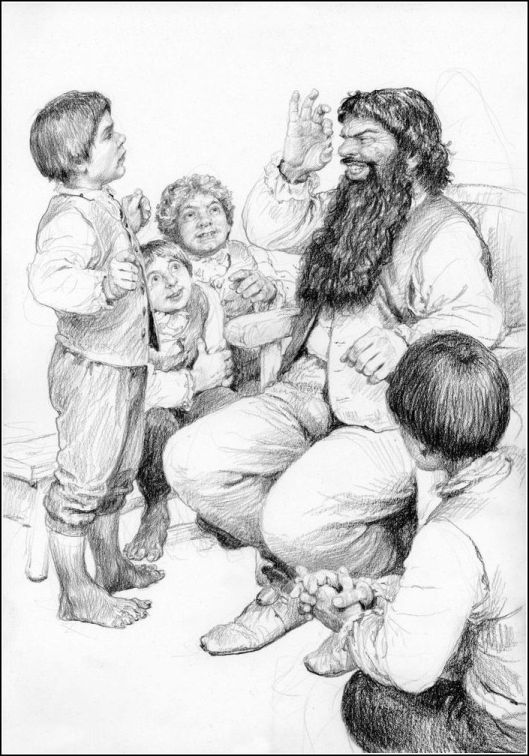

the implication that perhaps the title, The Last Jedi, is more of a puzzle than it would first appear. The very last line of The Lord of the Rings, spoken by Sam, is “Well, I’m back…” and it’s true, as far as Sam won’t go off on another adventure. Before this, however, Frodo has been busy writing:

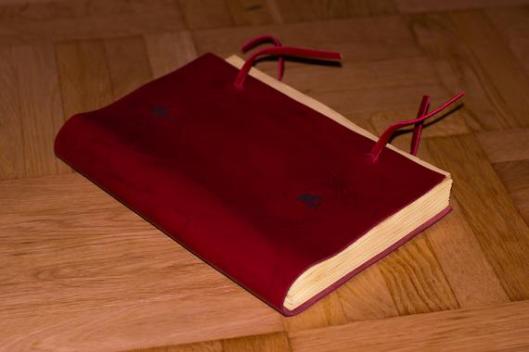

“There was a big book with plain red leather covers; its tall pages were now almost filled. At the beginning there were many leaves covered with Bilbo’s thin wavering hand, but most of it was written in Frodo’s firm flowing script. It was divided into chapters but Chapter 80 was unfinished, and after that were some blank leaves…

‘Why, you have nearly finished it, Mr. Frodo!’ Sam exclaimed. ‘Well, you have kept at it, I must say.’

‘I have quite finished, Sam,’ said Frodo. ‘The last pages are for you.’”

But what does this imply? We have no idea what Sam may have added, but the volume Frodo gave him was the origin of The Red Book of Westmarch, the basis not only for The Lord of the Rings, but for The Hobbit, as well. Are we being told that writing about adventure is an adventure in itself, and almost as important?

Thanks, as always, for reading.

MTCIDC, of course!

CD

ps

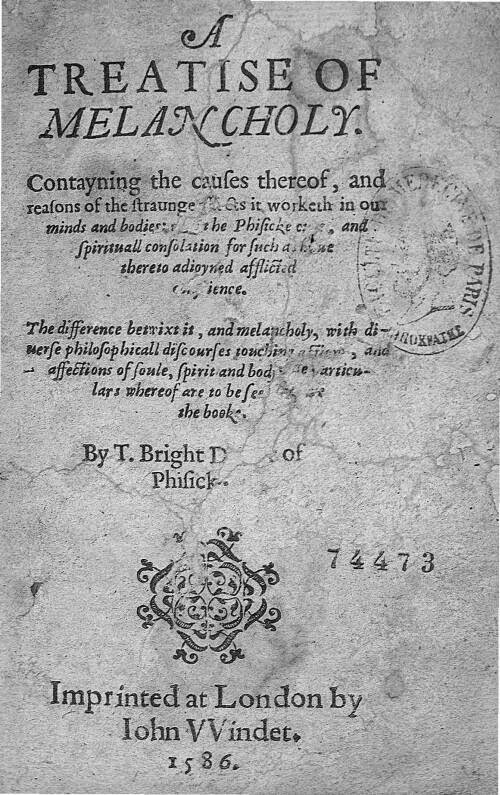

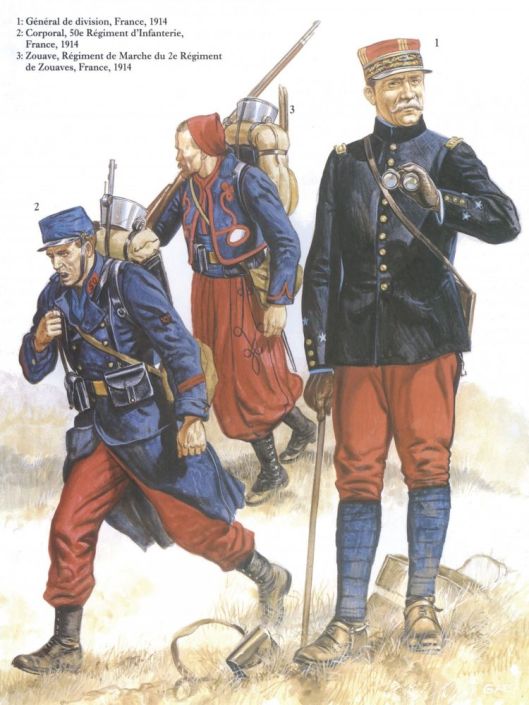

When we think of music in triumphs, the first piece which pops into our minds (after the Gungan march, of course) was one written by Haendel (1685-1759), “See, the Conquering Hero Comes”.

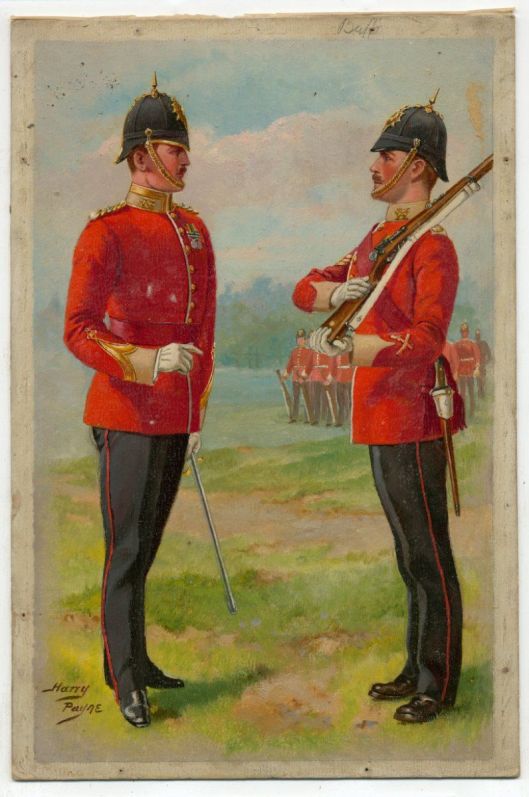

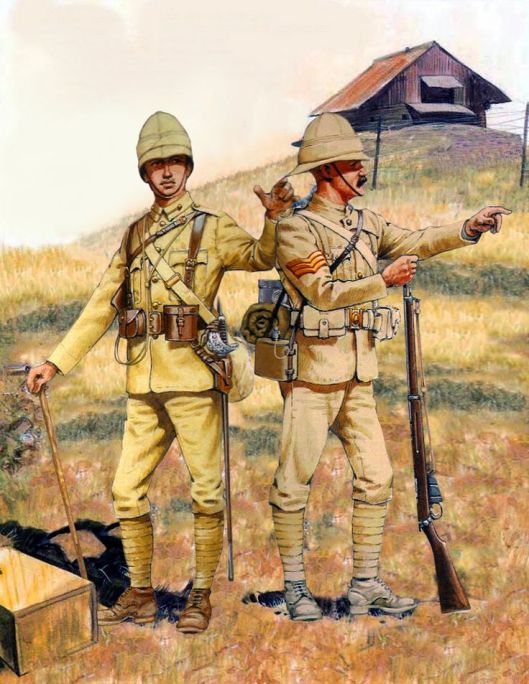

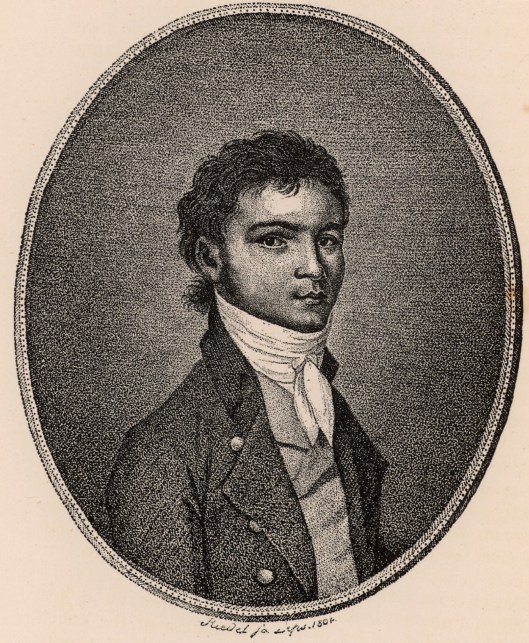

It was originally intended for his oratorio, Joshua (1747), but it fit his earlier piece, Judas Maccabaeus (1746) so well that he transferred it to the score of that oratorio. Judas Maccabaeus was composed as a tribute to the second son of George II of England, William Augustus, the Duke of Cumberland,

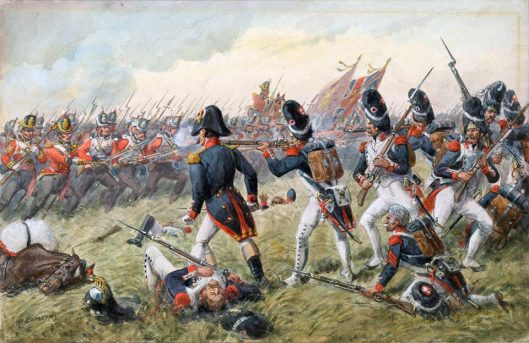

after he had decisively beaten the attempt to overthrow his father and replace him with the son of the former monarch, James II, at the battle of Culloden.

Here’s a LINK to a stirring performance.

In 1796, the young Beethoven (1770-1827)

wrote a series of 12 variations on the theme for cello and fortepiano. It’s a lot of fun to hear what Beethoven can do with Haendel’s tune, so we give you a LINK here.

Her armor is full plate, which, in our world, is later medieval. As for the helmet, it somewhat resembles a visored sallet, but only vaguely.

Her armor is full plate, which, in our world, is later medieval. As for the helmet, it somewhat resembles a visored sallet, but only vaguely.