Tags

Alan Lee, And Inquiry Into Ancient Armour, Angus McBride, arming sword, Battle Axe, English Longbowmen, Eowyn, Falchion, Gladius, Gondor, Hildebrandts, Howard Pyle, John Howe, King Arthur, Longbow, Mace, Medieval, Mongols, Morning Star, Orcs, Pelennor, Pitt-Rivers Museum, Robert Louis Stevenson, Rohirrim, Scimitar, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, Sir Samuel Meyrick, Ted Nasmith, The Black Arrow, The Lord of the Rings, The White Company, Tolkien, Victorian, Wallace Collection, War Hammer, Weaponry, Witch-King of Angmar

Welcome, dear readers, as always.

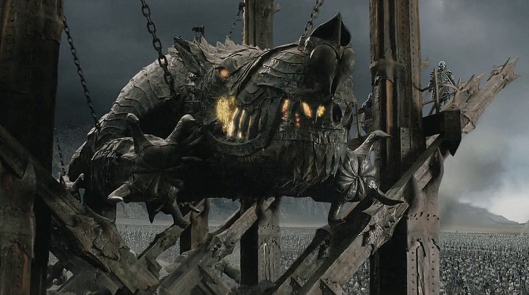

“The great shadow descended like a falling cloud. And behold! It was a winged creature…

Upon it sat a shape, black-mantled, huge and threatening…A great black mace he wielded.”

(The Return of the King, Book Five, Chapter 6, “The Battle of the Pelennor Fields”)

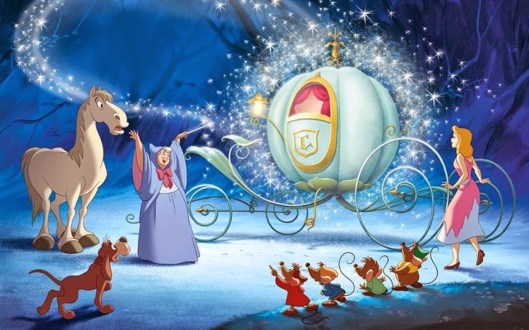

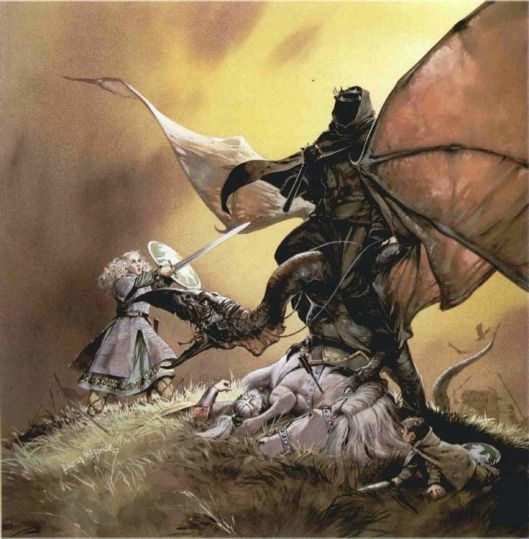

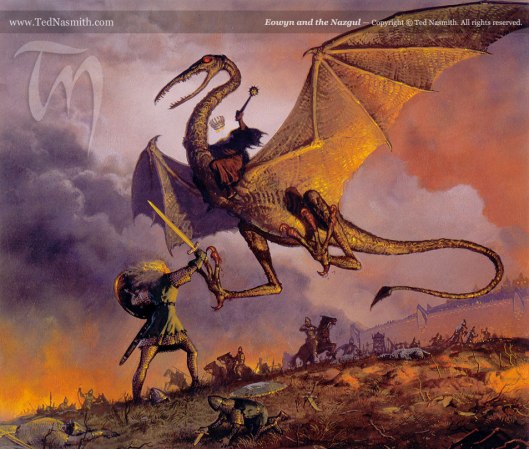

This is clearly a scene which has caught the attention, over the years, of many artists, starting, we’d guess, with the Hildebrandts.

Then others, like Angus McBride and Ted Nasmith,

And Alan Lee and John Howe,

as well as many very good artists whom we don’t know by name—

Of these, all but Lee and the unknown sixth artist follow JRRT’s description more or less closely. Number 6—it’s a little unclear– but he might be carrying a war hammer of some sort,

rather than a mace.

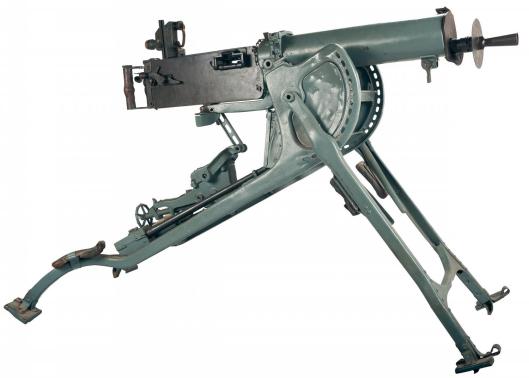

(These last two are basic patterns of a mace.)

The Lee is, well, we’re not sure what it seems to be. It sort of looks like a battle axe

but also like what was called a “morning star”,

which should, we think, belong to the flail family.

This rather fits in with the P Jackson image, shown in this model (and note that sword—definitely not in the original description—which is in his other hand).

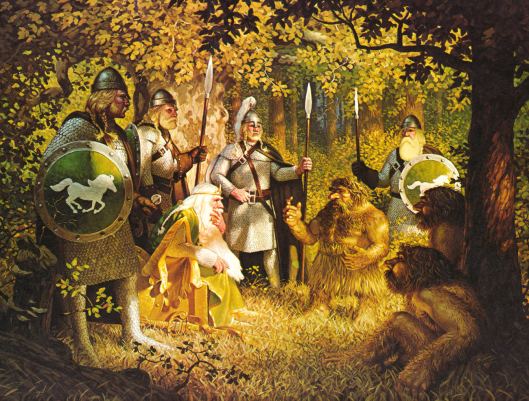

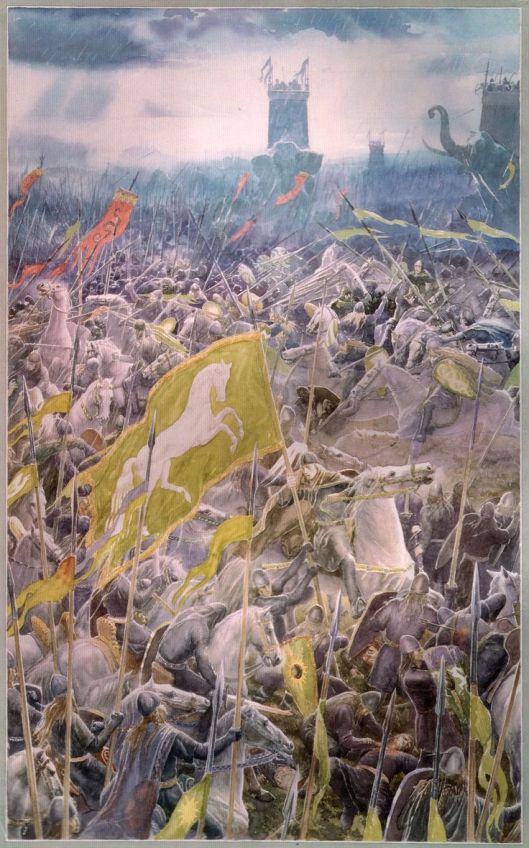

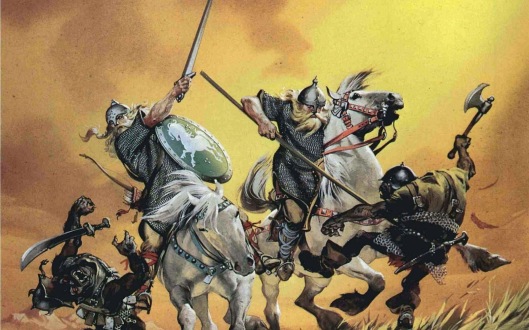

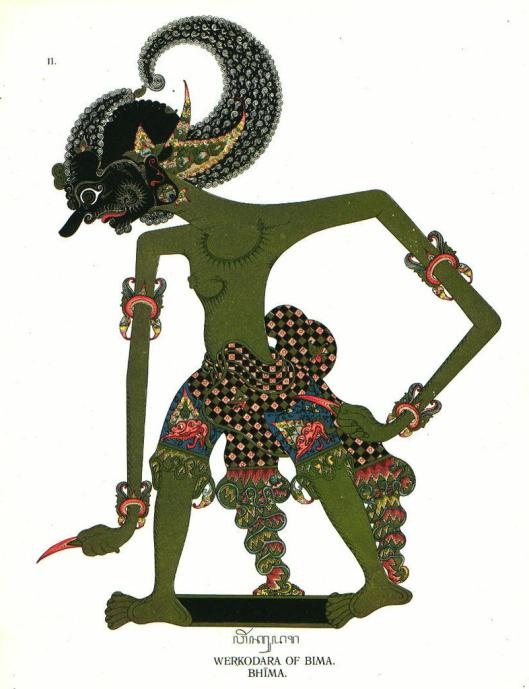

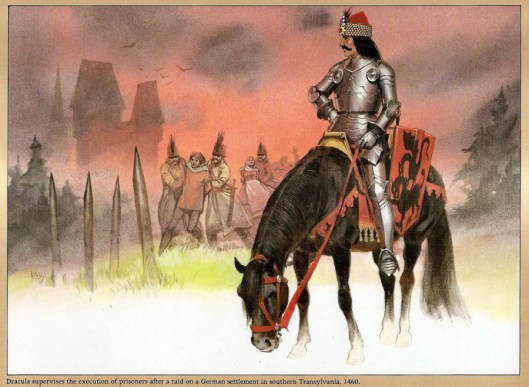

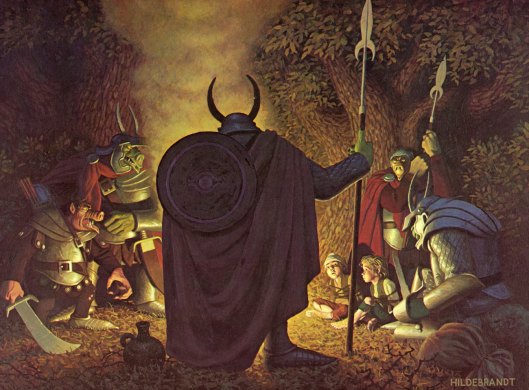

This difference made us curious about the weapons the Rohirrim—and the Gondorians—face and, in particular, those of the orcs. The Hildebrandts

provide us with odd-looking spears and what might appear to be scimitars

but might be the suggestion of a medieval sword called a falchion.

McBride, who spent much of his artistic career illustrating military subjects, gives us weapons (mostly) less fanciful.

Lee

and Howe

veer between the practical and the fantastic and the films clearly follow them—

How does JRRT describe the orc weaponry?

The first armed orc we see appears in Moria:

“His broad flat face was swart, his eyes were like coals, and his tongue was red; he wielded a great spear…Sam, with a cry, hacked at the spear-shaft, and it broke. But even as the orc flung down the truncheon and swept out his scimitar…” (The Fellowship of the Ring, Book Two, Chapter 5, “The Bridge of Khazad-dum”)

The orcs who pursue the Fellowship through Moria have similar weapons:

“Beyond the fire he saw swarming black figures: there seemed to be hundreds of orcs. They brandished spears and scimitars which shone red as blood in the firelight.”

After the death of Boromir, however, Aragorn, Gimli, and Legolas find a different kind of orc:

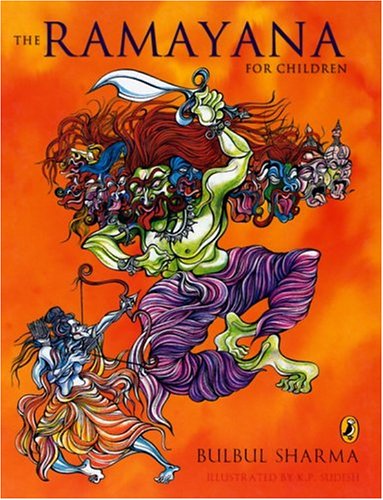

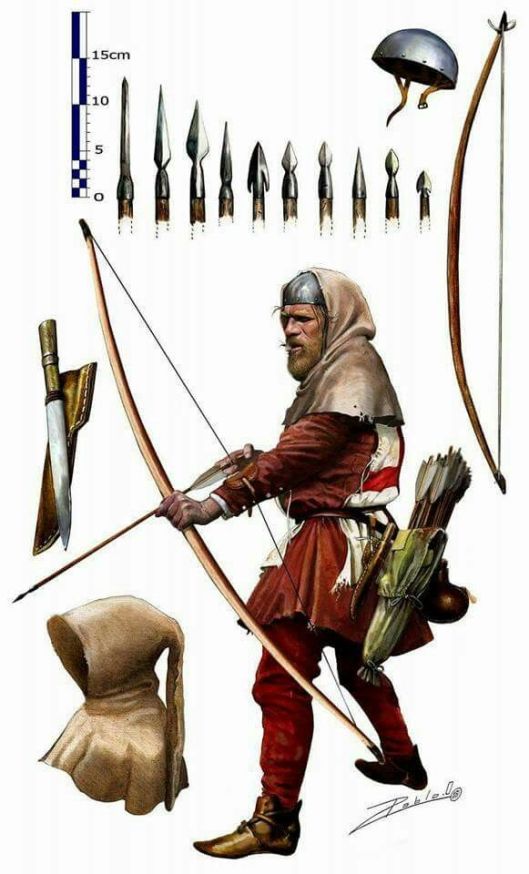

“There were four goblin-soldiers of greater stature, swart, slant-eyed, with thick legs and large hands. They were armed with short broad-bladed swords, not with the curved scimitars usual with Orcs: and they had bows of yew, in length and shape like the bows of Men.” (The Two Towers, Book Three, Chapter 1, “The Departure of Boromir”)

So far, we’ve seen spears

and scimitars

and now we can add to that “short broad-bladed swords”. Perhaps Tolkien is thinking of the medieval “arming sword”

or even the Roman gladius?

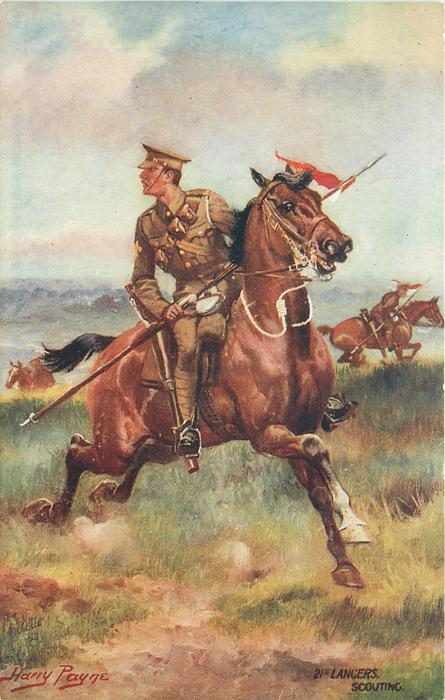

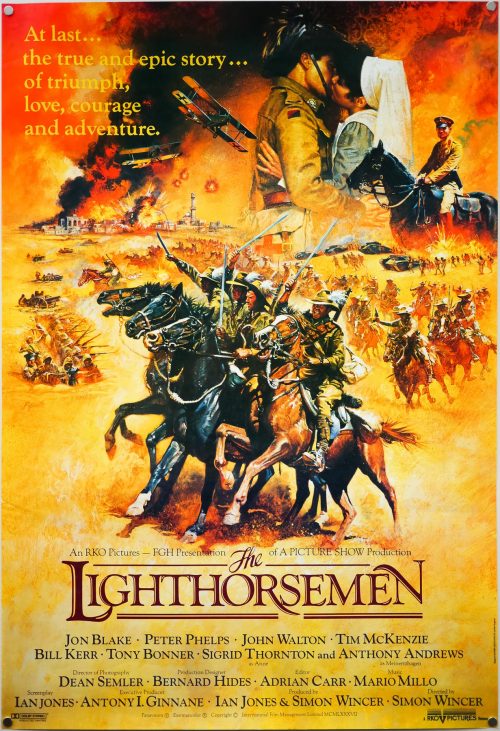

When we add “bows of yew, in length and shape like the bows of Men”, we immediately see the classic English longbow.

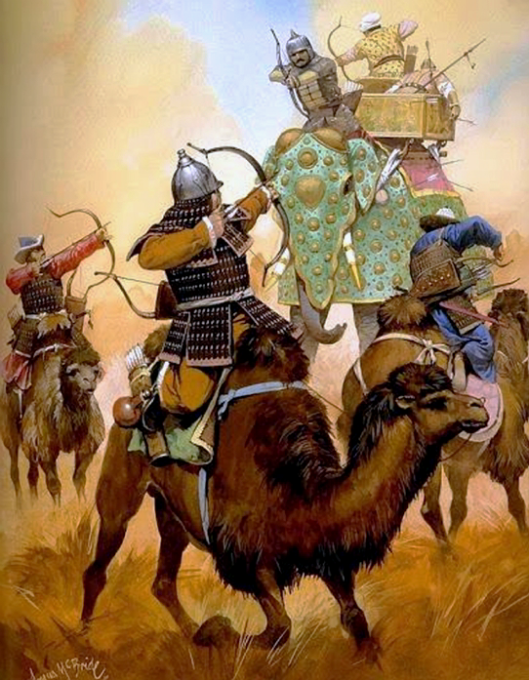

This doesn’t quite match with the first orc bowman we see in the films, however, “Lurtz”—

who appears to have some sort of recurved bow, possibly composite, of the sort the Mongols used

even though, from the white hand on his face, he is supposed to be one of those “goblin-soldiers” from Isengard.

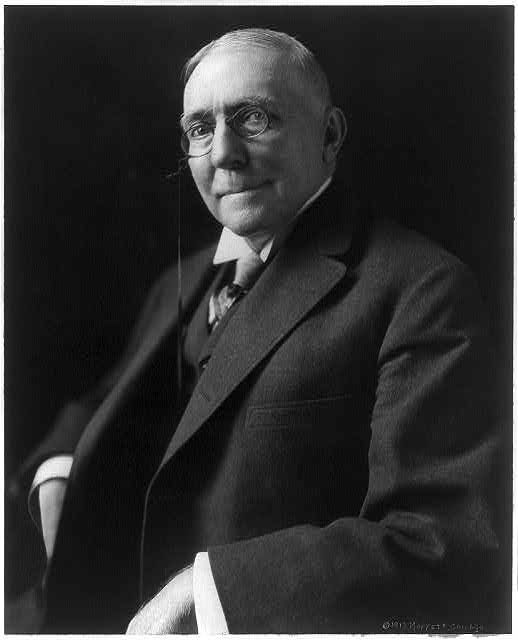

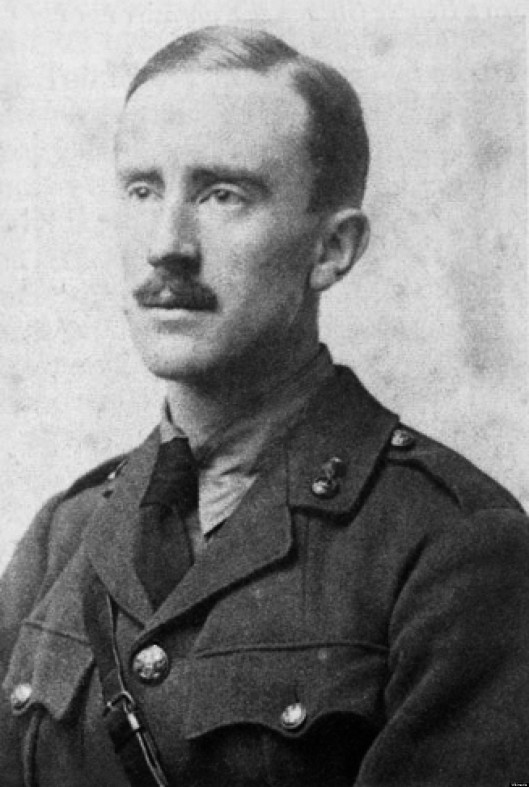

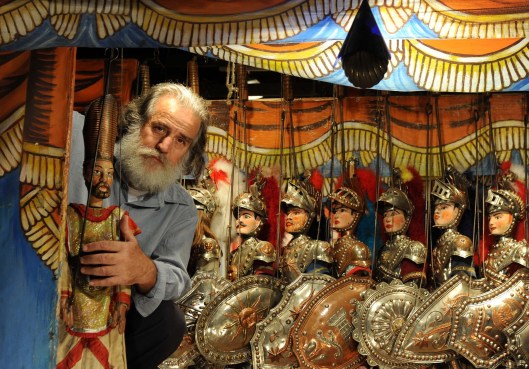

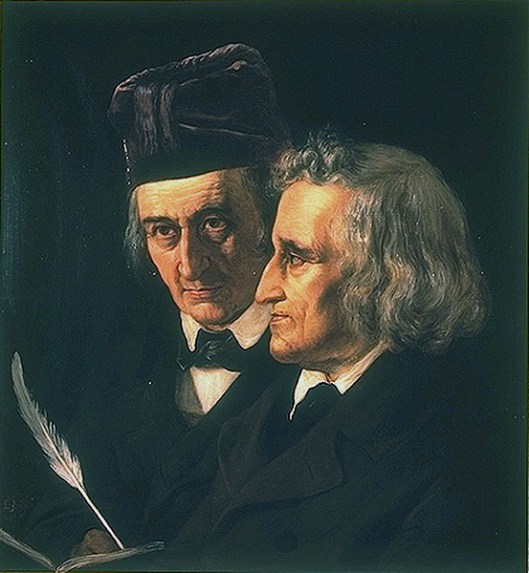

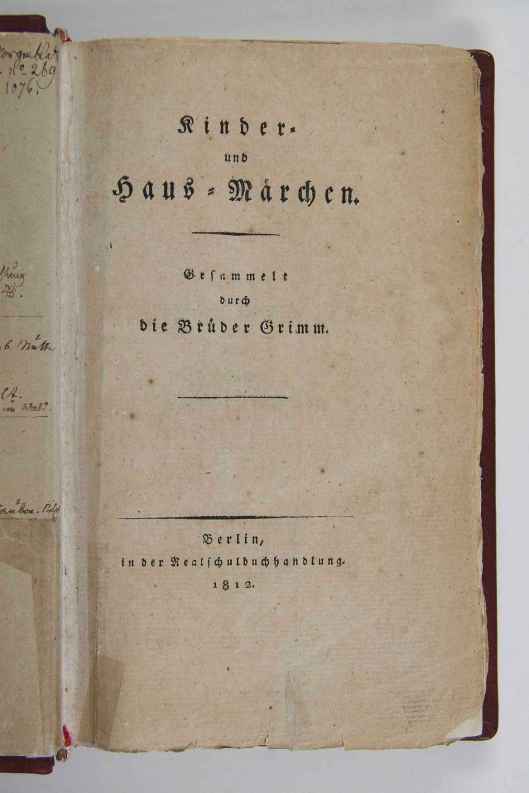

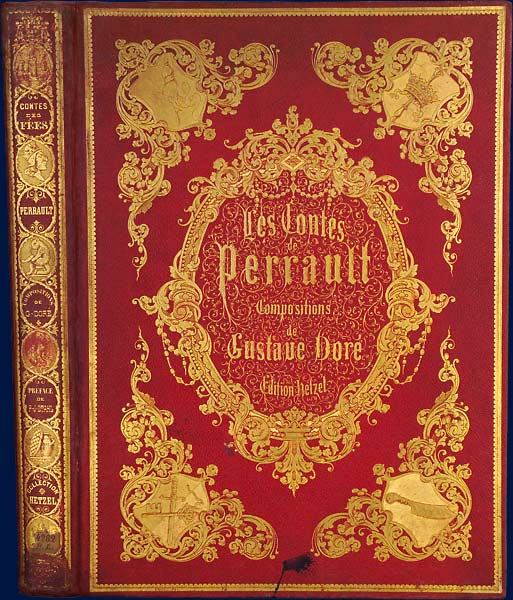

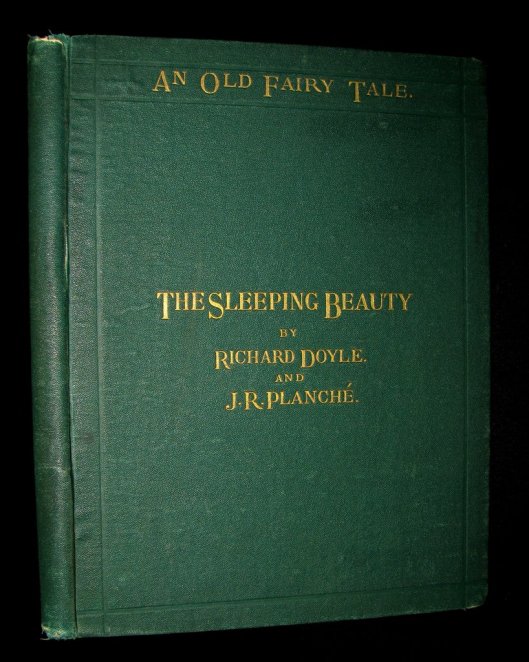

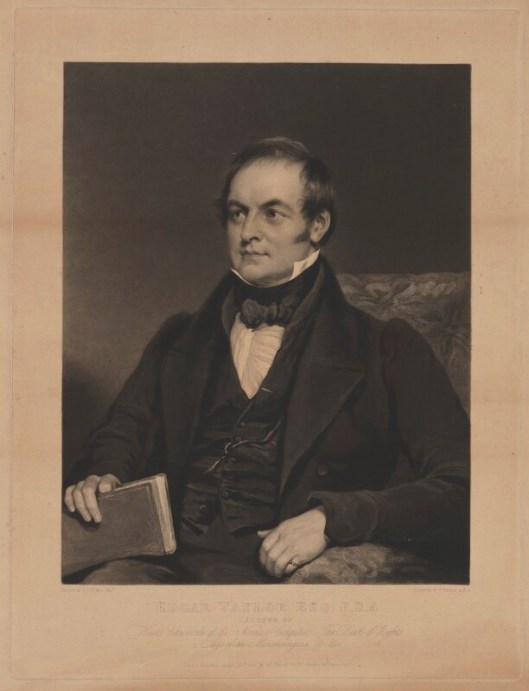

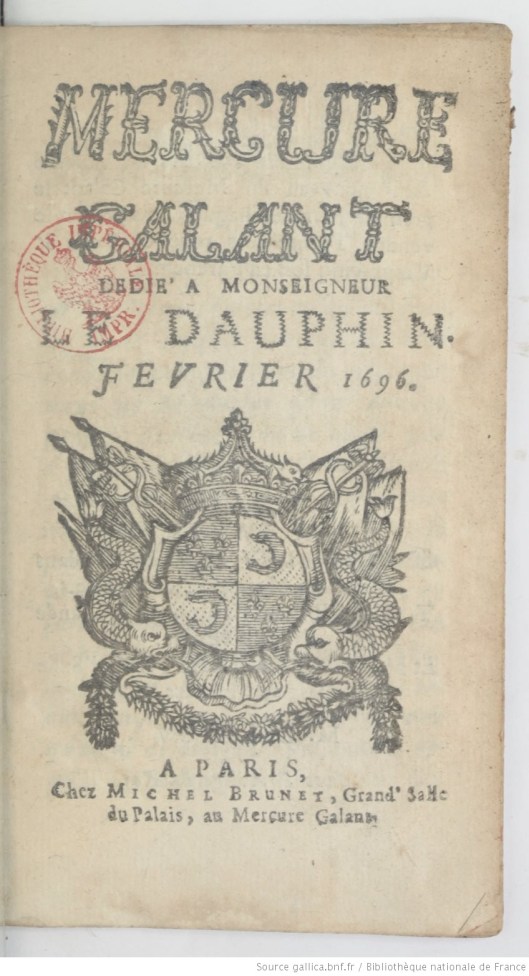

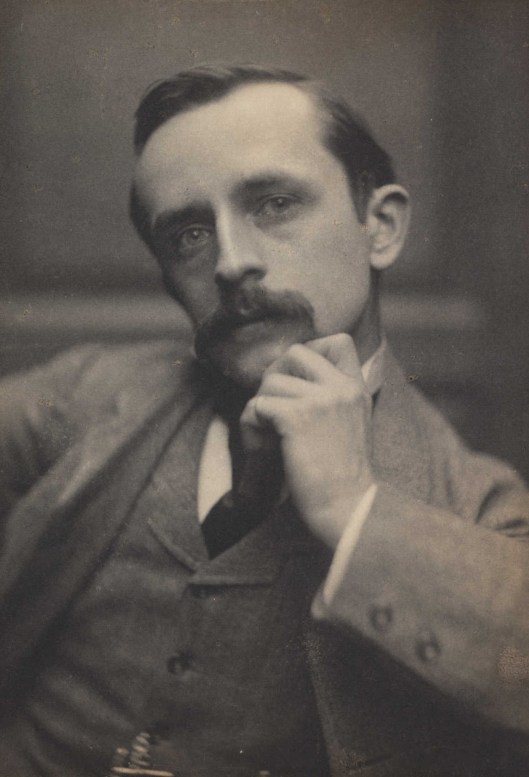

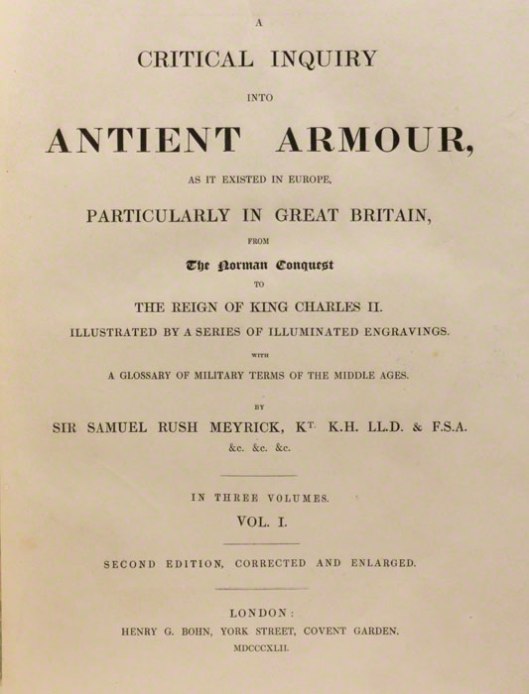

As we were looking through Tolkien’s text, we wondered where he would have gotten his ideas for weapons from. If the basis, as we imagine it, would have been his background in medieval literature, then he might have gone to the library and found an old standard work, Sir Samuel Meyrick’s (1783-1848)

An Inquiry Into Ancient Armour, As It Existed in Europe, Particularly in Great Britain, From the Norman Conquest to the Reign of Charles the Second, first published in 1824. (Here’s a LINK if you’d like to look at this text for yourself.)

Meyrick was the first great English specialist in armor and the later editions of his work (in 3 volumes) have wonderful early hand-colored plates, all based upon surviving armor, tombs, manuscripts, and any other period materials he could gather.

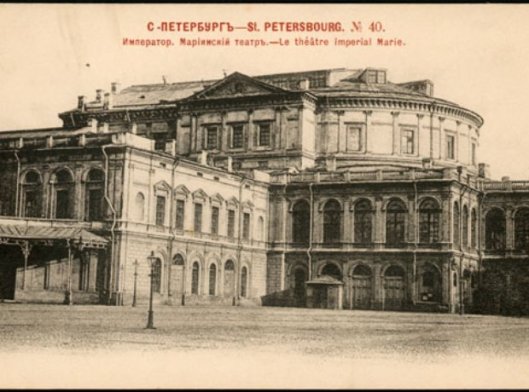

If JRRT wanted to see such things for himself, he would have found more exotic weapons in the Pitt-Rivers Museum in Oxford,

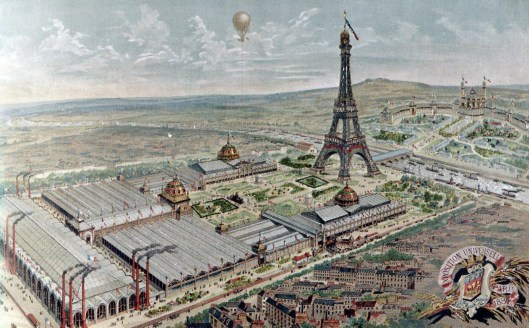

or he could have traveled up to London to see the Wallace Collection

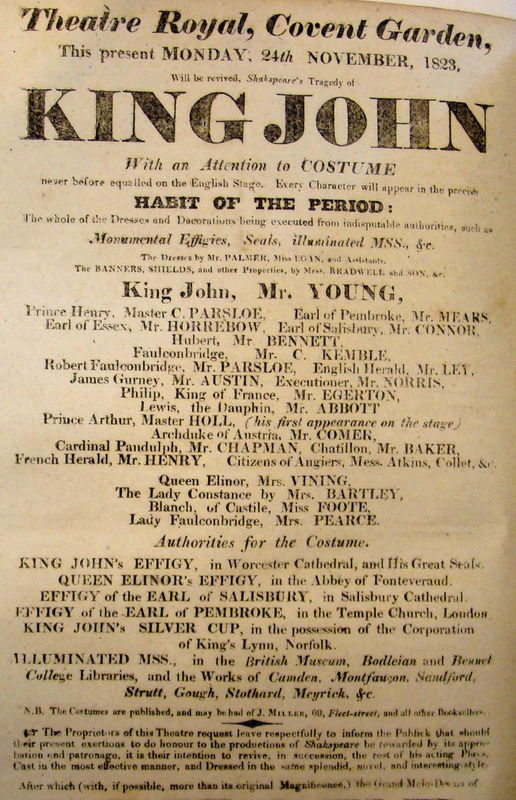

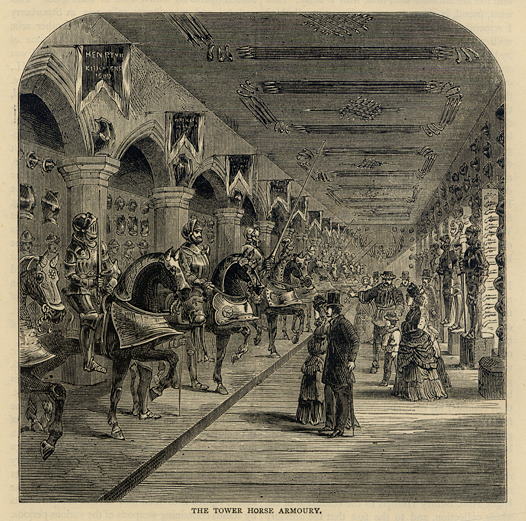

or, best of all, he could have visited the Tower of London, with its massive collection (the organizing of which had earned Meyrick his knighthood in 1832) of medieval arms and armor, which had been available to the public in some form even before Meyrick’s time—here’s a Victorian tour.

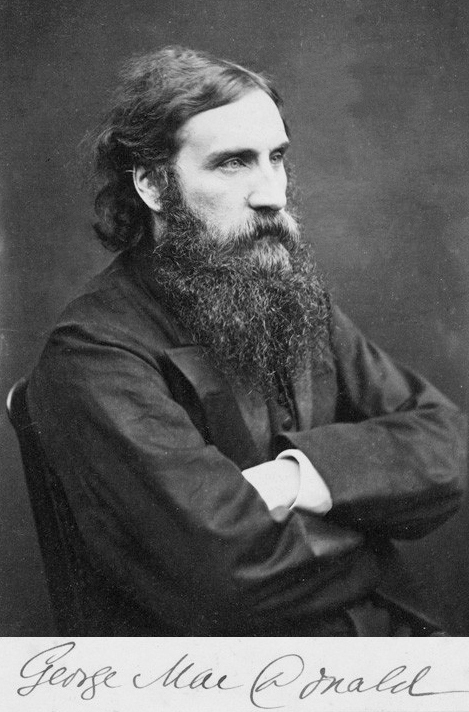

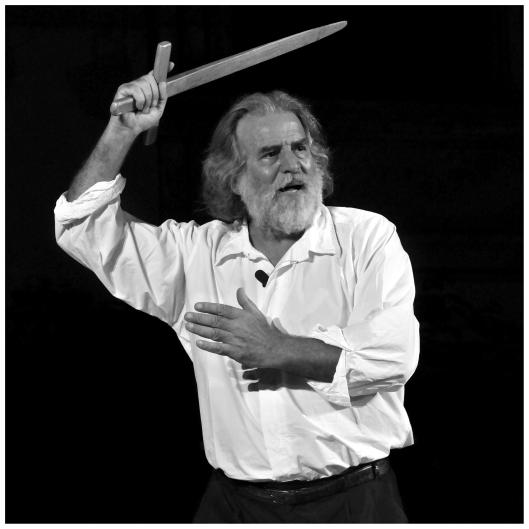

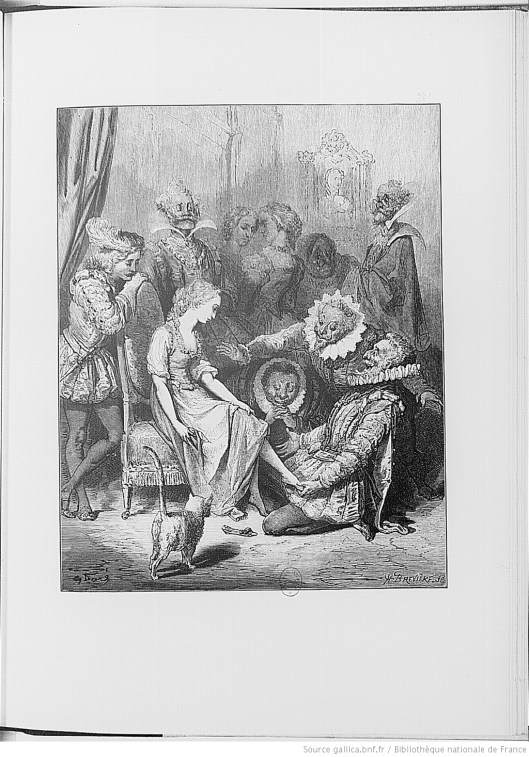

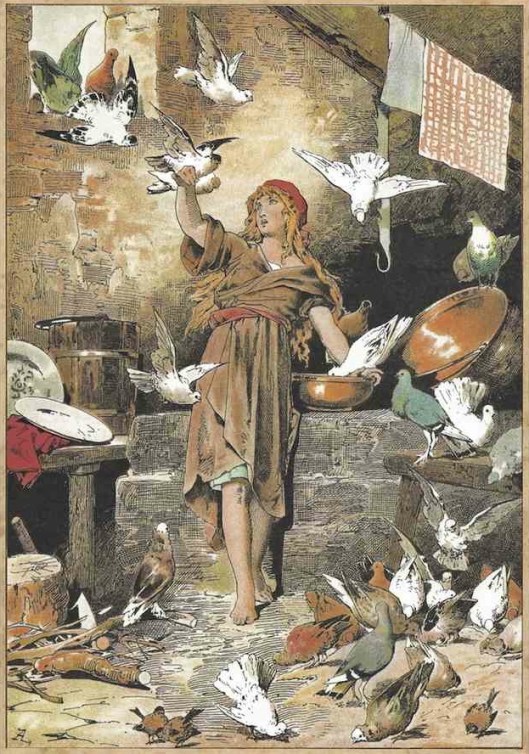

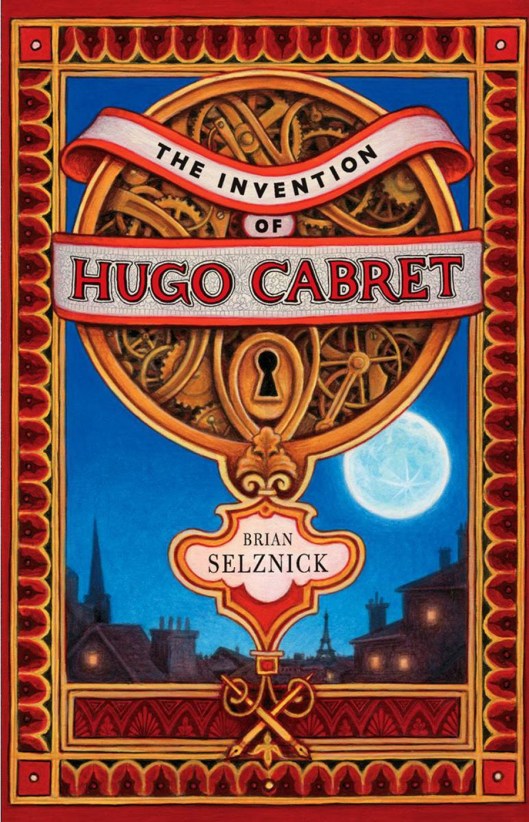

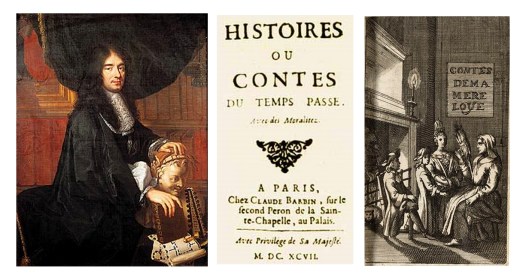

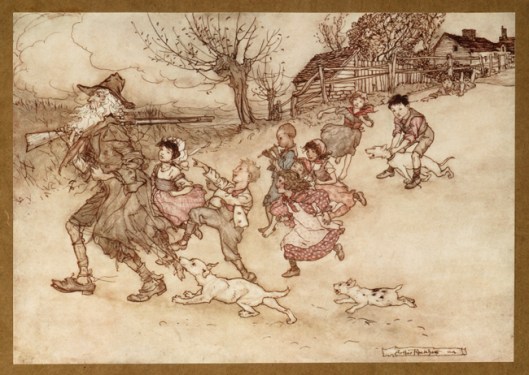

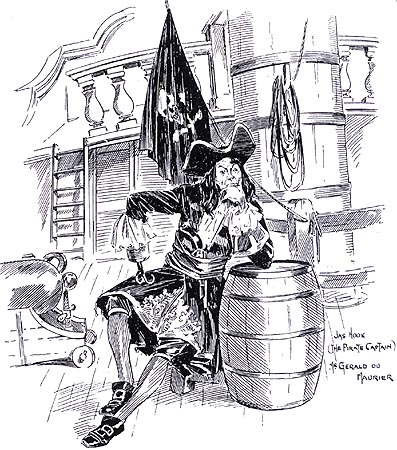

It could have been all of the above, of course, but it seems to us that the descriptions we’re reading are actually not really very specific—“mace”, “spear”, “scimitar”—only those short swords and bows suggest anything more detailed. Perhaps, then, Tolkien was inspired by something else—perhaps he had read, perhaps even possessed, as a boy, books like Howard Pyle’s 1903 The Story of King Arthur and His Knights

and been inspired by its illustrations.

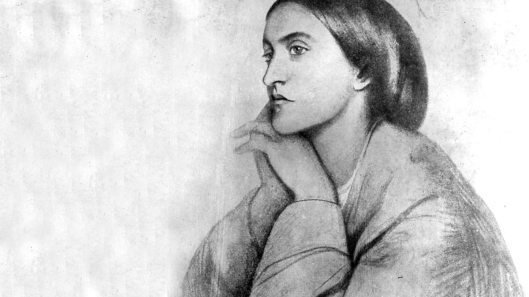

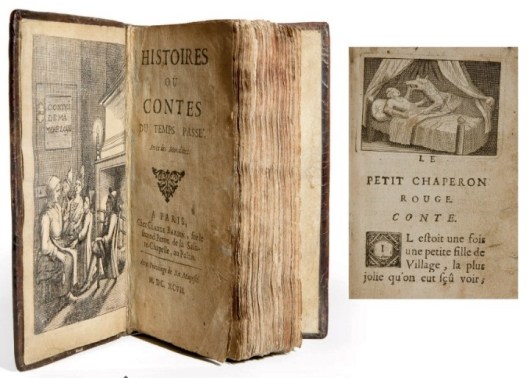

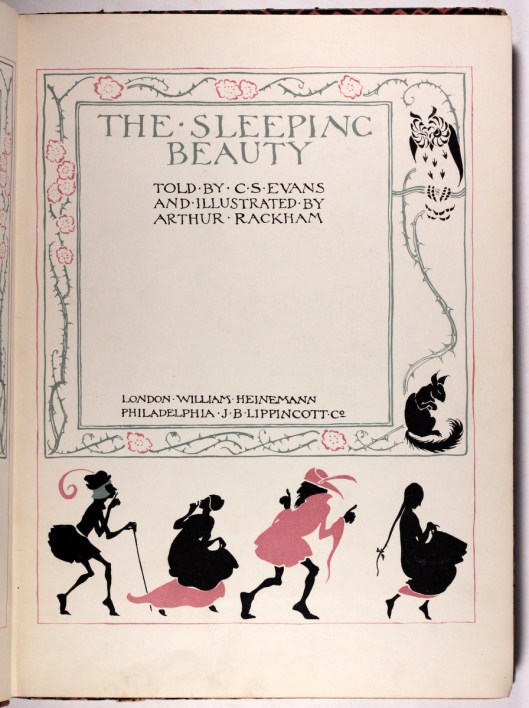

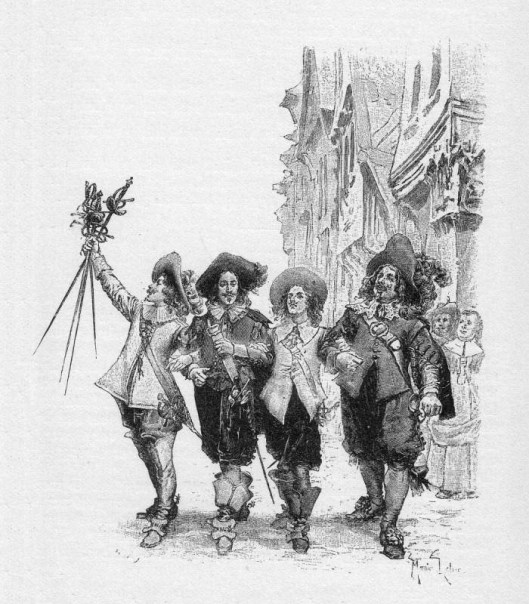

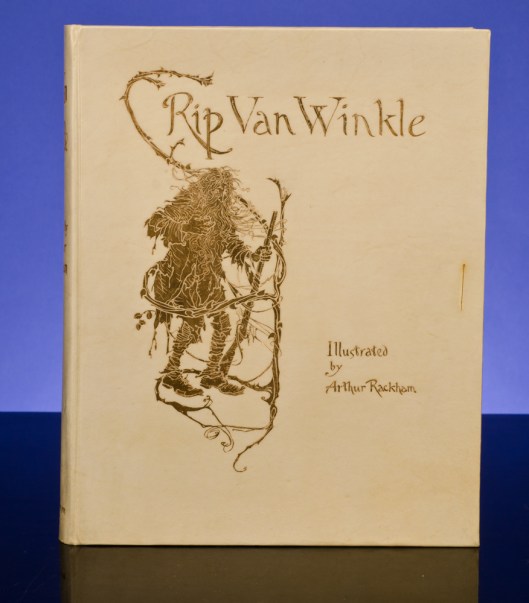

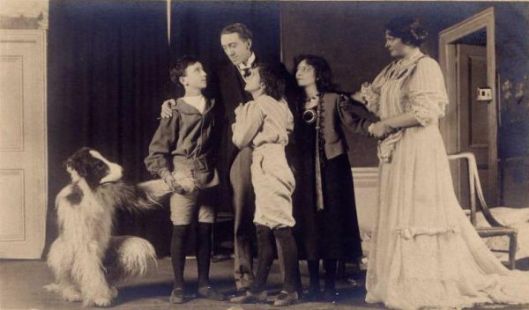

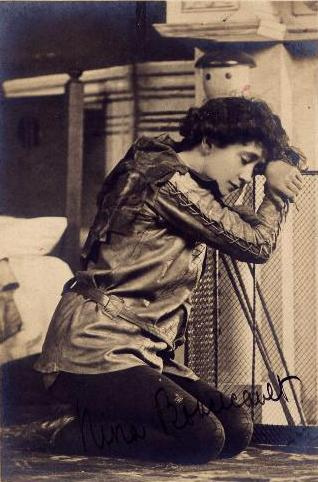

There were plenty of illustrated tales like this—Conan Doyle’s The White Company (first published in serial form in 1891),

or Robert Louis Stevenson’s The Black Arrow (serial 1883, book 1888).

With any and all of that background, we wonder what he might have made of this, however, an orc sword from the films which looks more like something manufactured from a car part than the product of a medieval armorer…

Thanks, as ever, for reading.

MTCIDC

CD

ps

If car part weapons don’t bother you, you might be interested in this LINK—it’s an early article on ideas for weapons and armor for the Jackson films.