Dear readers, welcome, as always.

“Ye Hielands and ye Lowlands,

O, whaur hae ye been?

They hae slain the Earl o’ Moray,

And laid him on the green.”

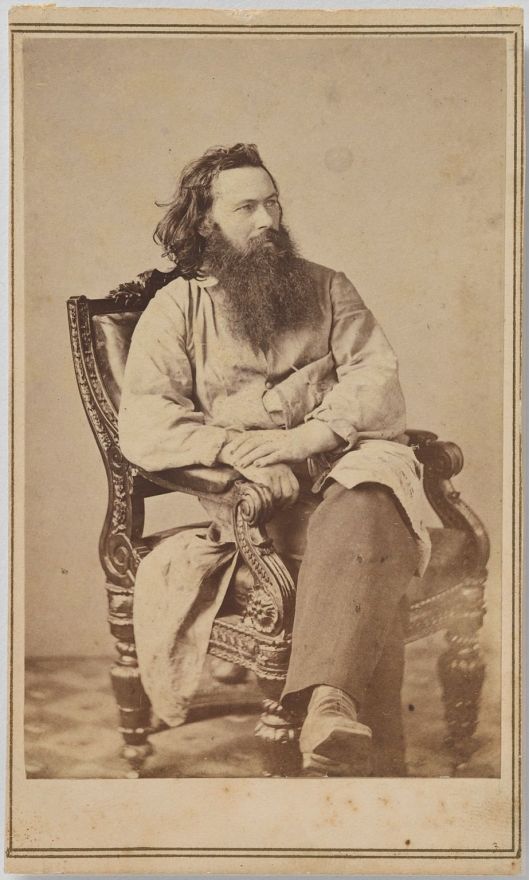

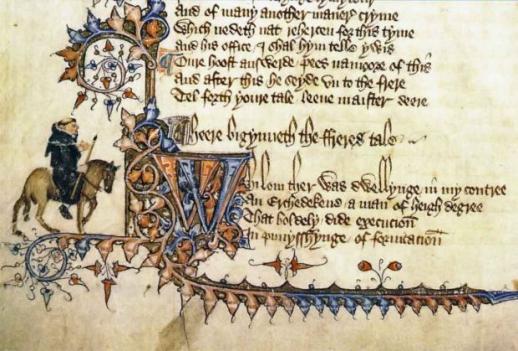

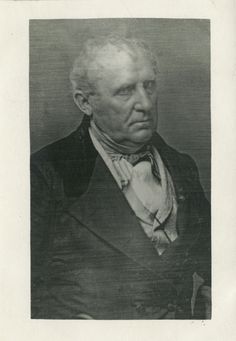

So begins a version of Child Ballad #181. As we are lucky enough to have readers from around the world (and thank you, every one of you, for visiting!), we might explain that a Child Ballad is not a nursery rhyme, but a distinctive type of traditional song from the massive collection of 305 such songs made by Francis James Child, a professor at Harvard, and published in five volumes between 1882 and 1898 under the title The English and Scottish Popular Ballads.

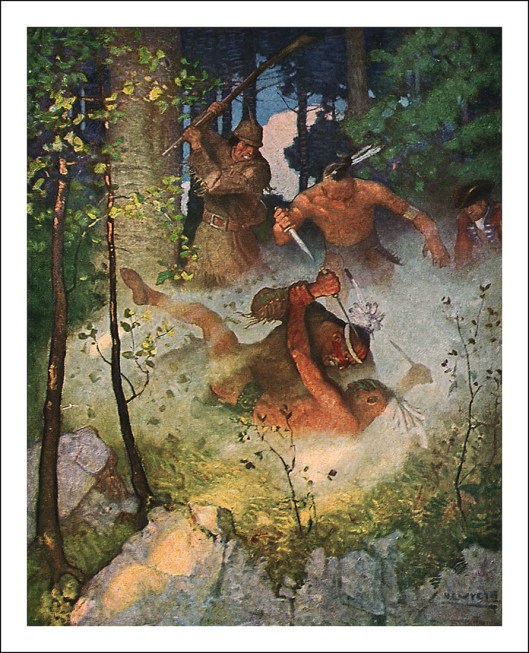

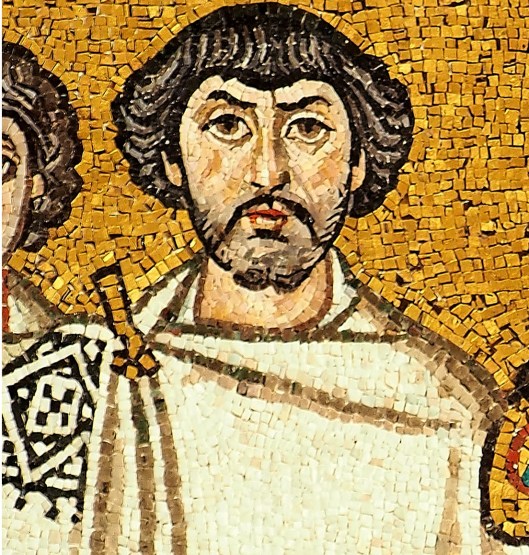

Ballads are verse narratives, sometimes based upon folk tales, sometimes based upon actual historical events. This particular ballad is historically-based and concerns a murder in 16th-century Scotland. For our purposes, its actual historicity doesn’t matter, however, because what we’re really interested in is the fact that this is a lament for the murdered man, James Stewart, the Earl of Moray (pronounced “Murray”). We also have this posthumous painting, commissioned by his mother, to draw attention to the crime, but it doesn’t appear to have made much difference.

There are a number of different versions of this ballad, but the one which we heard first and with which we are most familiar (and from which we originally learned a tune—there’s more than one) was recorded by the famous Scots folksinger, Ewan MacColl, and is still available on the Smithsonian/Folkways CD FW03509/FG3509, “The English and Scottish Popular Ballads, Vol.1”.

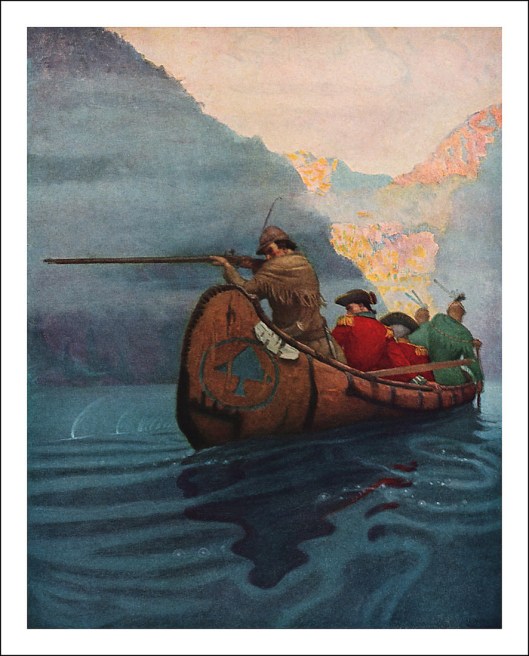

As we said, it’s a lament—just like that for Boromir in the chapter entitled “The Departure of Boromir”–and that’s really where we began to think about laments, especially a lament for a prominent person. And, as ever, we looked for a useful parallel between our world and that of Middle Earth. In this case, the murdered man in the ballad was an earl—a high-level nobleman—but he was also the son of the Regent (the temporary ruler) of Scotland and so we might see him as on about the same social level as Boromir the son of the Steward of Gondor.

Here’s how the lament for Boromir begins.

“Through Rohan over fen and field where the long grass grows

The West Wind comes walking, and about the walls it goes.

‘What news from the West, O wandering wind, do you bring to me tonight?

Have you seen Boromir the Tall by moon or by starlight?’ ”

You can see a similarity between this and the ballad already. The ballad begins by addressing all of Scotland. The lament begins by addressing the West Wind. Both appeal to something more than a listener, or even a group of listeners, as if speaking to simple mourners wouldn’t be enough: bigger forces must be involved. In the case of the ballad, the speaker (unknown—but clearly well aware of the facts) asks where the country has been. In the lament, Aragorn (as he is the initial mourner) has a more specific addressee and a more specific question: West Wind, have you seen Boromir?

The ballad then goes right to the point:

“They hae slain the Earl of Moray

And laid him on the green.”

[A footnote here. That last line became famous because of an essay by Sylvia Wright in the November, 1954 issue of the American publication, Harper’s Magazine entitled “The Death of Lady Mondegreen”. In the essay, Wright explains that, as a child, she misheard “and laid him on the green” as “Lady Mondegreen” and imagined that Stewart had been murdered along with a female companion. The word “mondegreen” has become a technical term in language studies for a misheard word which produces a new meaning.]

The next part of Aragorn’s lament is unspecific: Boromir is simply missing.

“ ‘I saw him ride over seven streams, over waters wide and grey;

I saw him walk in empty lands, until he passed away

Into the shadows of the North. I saw him then no more.

The North Wind may have heard the horn of the son of Denethor.’

‘O Boromir! From the high walls westward I looked afar,

But you came not from the empty lands where no men are.’”

The ballad then tells us something about the quality of the dead man.

“He was a braw gallant,

And he rade at the ring,

And the bonny Earl o’ Moray,

He might have been a king.”

This might need a little translation. The ballad is written in Lallans, the English—and we might really say the wonderfully rich English—originally of southern Scotland (Lallans= “Lowlands”). In general, the grammar and syntax are recognizably English, but the expressions and vocabulary are sometimes different—and sometimes very different!

So, here (so far):

Braw = “fine/splendid”

Gallant = “young man” (can also be spelled “callant”)

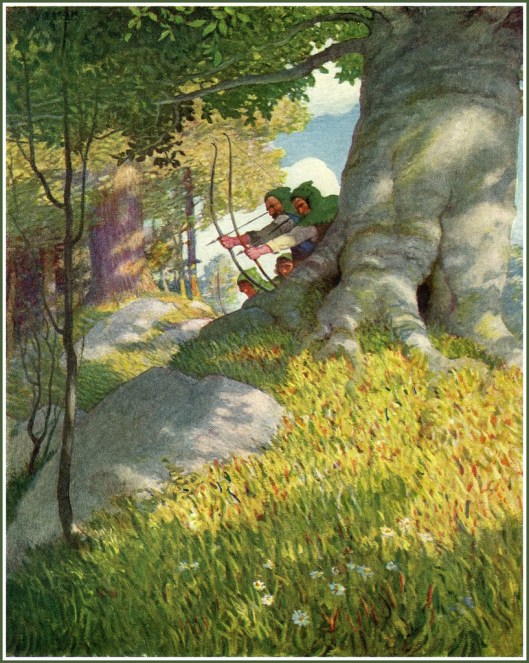

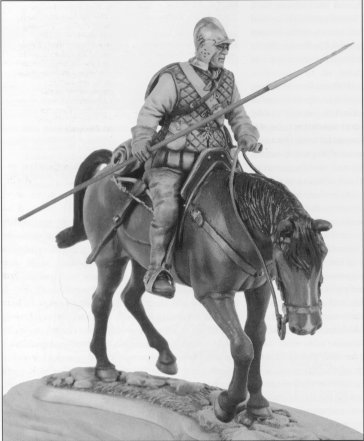

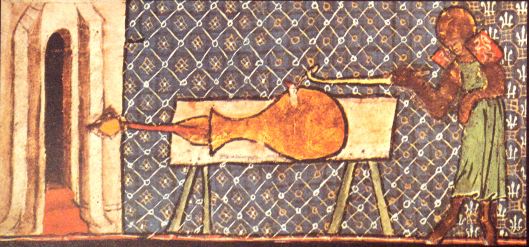

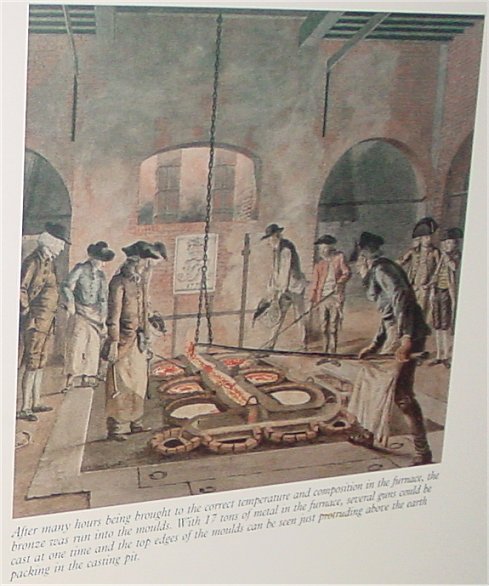

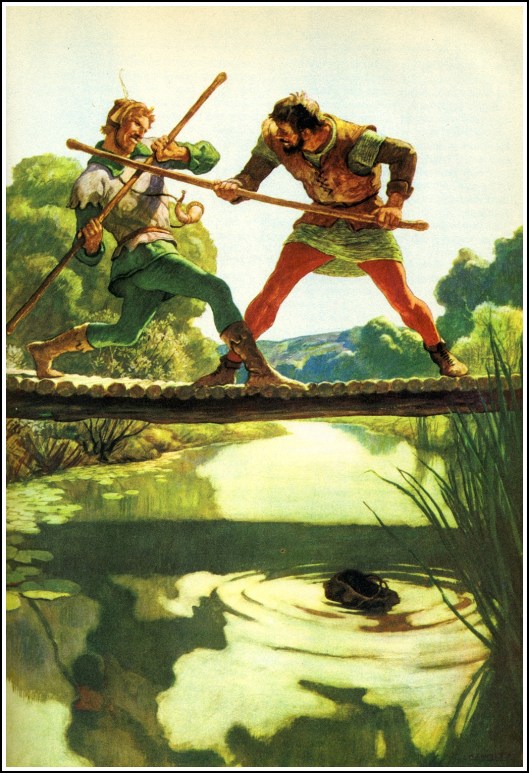

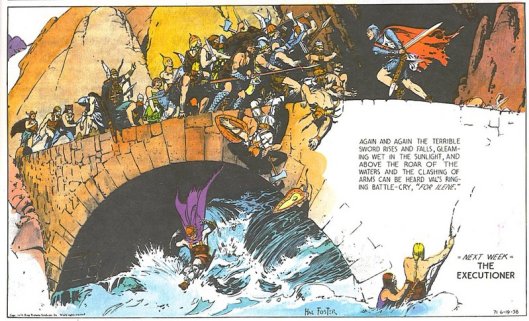

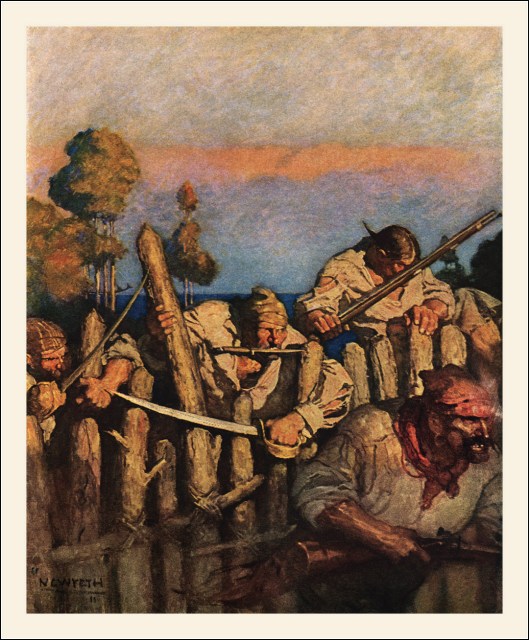

But the next expression is actually from medieval jousting. This was a game in which a knight would be required to ride at a ring, suspended in mid-air, and spear it on the end of his lance. Here’s an illustration from the 1839 Victorian tournament revival at Eglinton, in Scotland.

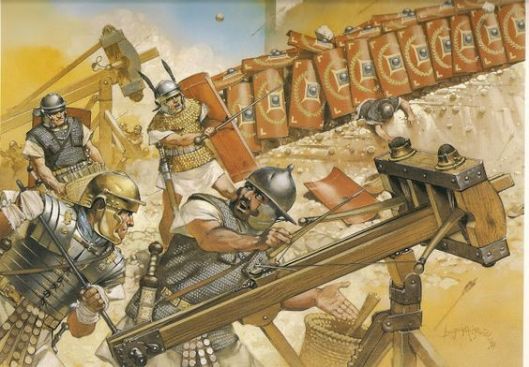

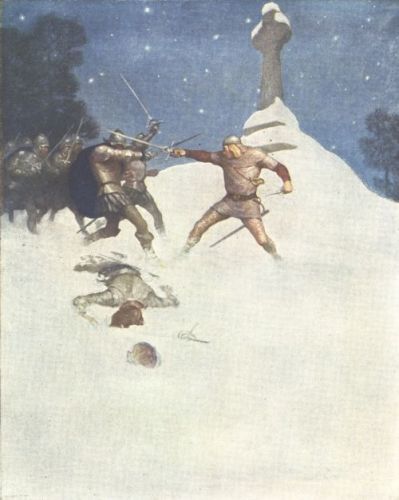

Although we might normally imagine that tournaments died out with the Middle Ages,

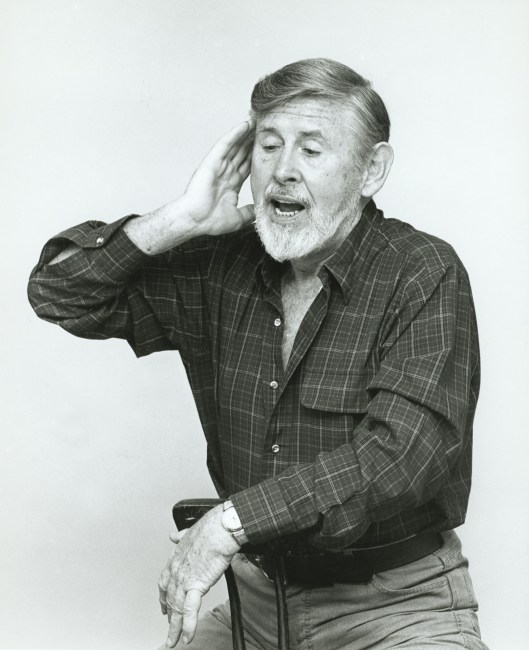

Elizabethans and their successors, the Jacobeans, still jousted, as a kind of expensive archaic sport. Here’s Nicholas Hilliard’s c1590 portrait of George Clifford, 3rd Earl of Cumberland, dressed for a tournament as the Queen’s Champion.

So, we know that the speaker believes that James Stewart was a fine young man, and able at tournaments. We also know that Stewart was able enough—as far as the speaker is concerned—to be a king. As his father had been the Regent for the infant James VI, perhaps this is a quiet suggestion that James junior might have done better on the throne than James.

In contrast, all we know at the moment about Boromir was that he was tall and that his father’s name was Denethor, with the suggestion that he was on an errand or quest in some deserted land.

But then we find out more about James Stewart.

“O lang will his lady

Lok frae the Castle Doune

Ere she see the Earl o’ Moray

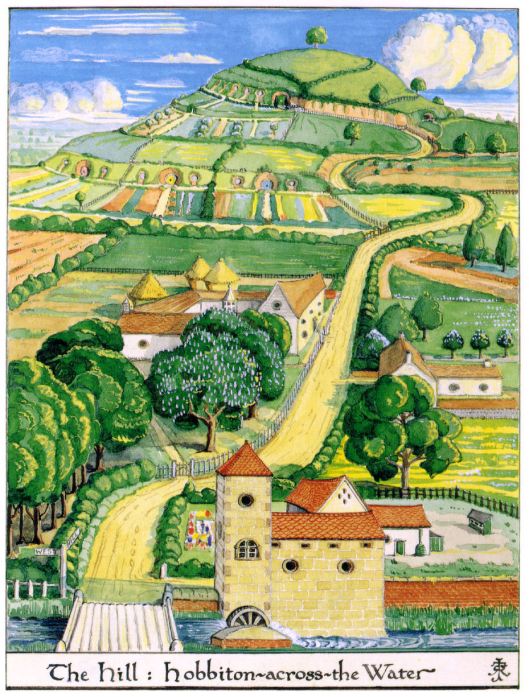

Come soundin’ through the toun.”

He had a wife or mistress and we see something about where he lived: in a castle. If you just heard this ballad, rather than reading it, and you came to the next word, “Doune”, you might be confused, since you can hear “doune”, meaning “down” in Lallans. This gives you a picture of a lady standing on the castle wall, waiting for Stewart to return, which is fine, but Doune is also the name of a castle owned by James Stewart.

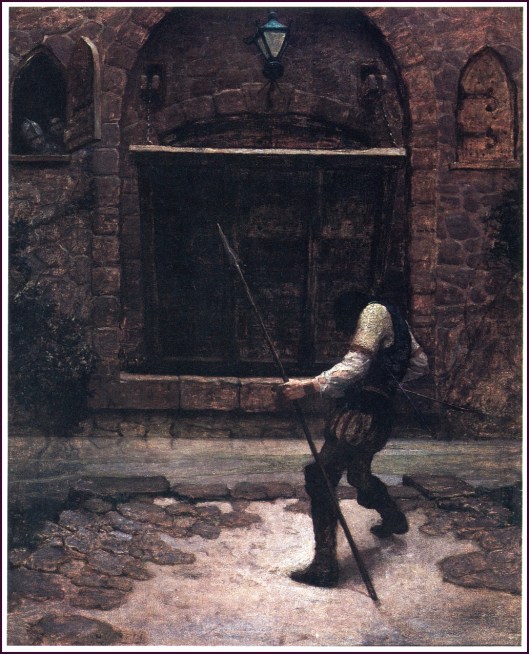

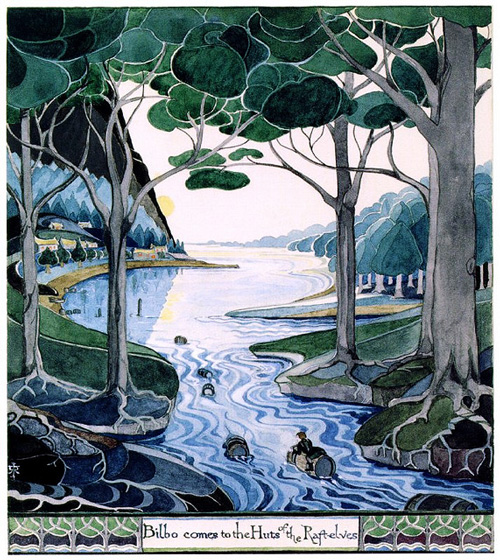

If you’ve seen Monty Python and the Holy Grail, you will recognize this place.

Or, if you watch Outlander.

As for the last line, we imagine that the Earl has a trumpeter ride in front of him, to clear the way.

Will we learn more about Boromir from the second stanza, which Legolas sings?

“From the mouths of the Sea the South Wind flies, from the sandhills and the stones;

The wailing of the gulls it bears, and at the gate it moans.

‘What news from the South, O sighing wind, do you bring to me at eve?

Where now is Boromir the Fair? He tarries and I grieve.’ “

With the idea that the speaker is appealing to nature for answers, we see Legolas address a second wind, but, so far, all we have added to our store of knowledge is that Boromir was good-looking (“the Fair”—and, in English, this can also mean “light-skinned/light-haired”)—and the anxiety at his absence continues.

In the ballad, we move farther into the crime, the actual murderer being spoken to.

“Now wae be to ye, Huntly,

And wherefore did ye sae?

I bade ye bring him wi’ ye,

And forbade ye him to slay.”

A little glossing first.

Wae be to ye= “may you be sad/sorrowful” (wae is Lallans for “woe”)

Bade= “ordered”

Forbade= “forbid/prohibited” (and should be pronounced “for-BAHD”)

Here we are presented—a bit obliquely—with the identity of the speaker of the ballad. He is one who gives order to lords—hence, he’s the king, meaning, historically, James VI of Scotland (soon—1603—to be James I of England, as well).

If we only go by the verse, he has ordered “Huntly” (historically, the Earl of Huntly, ordered by James VI to arrest Stewart) to bring the Earl of Moray to the king’s court. In real life, he murdered Stewart when Stewart tried to escape, and here we see that, literarily, the same thing is suggested.

At this point, we have three characters: king, Huntly, Moray, and a murder, supposedly against the king’s orders. What more does Legolas’ lament have to tell us?

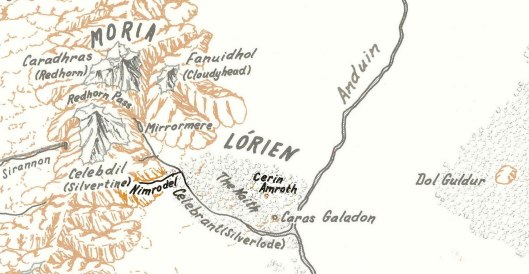

“ ‘Ask not of me where he doth dwell—so many bones there lie

On the white shores and the dark shores under the stormy sky;

So many have passed down Anduin to find the flowing Sea.

Ask of the North Wind news of them the North Wind sends to me!’

‘O Boromir! Beyond the gate the seaward road runs south,

But you came not with the wailing gulls from the grey sea’s mouth.’ ”

Nothing is said directly here, but that first line’s mention of “so many bones” might be seen to reveal what has happened to Boromir. The South Wind tells the speaker to ask the North Wind, but will that make a difference?

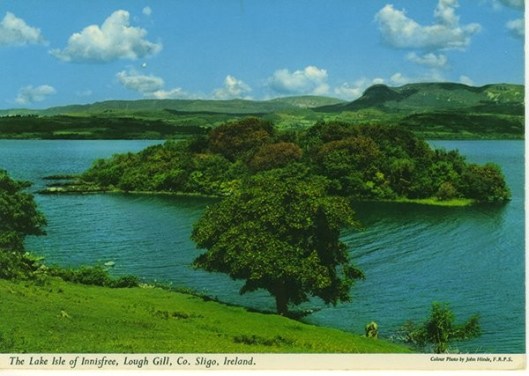

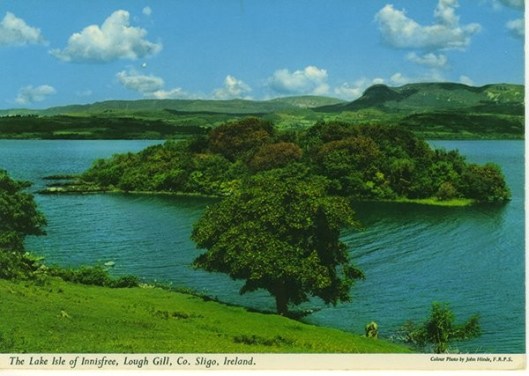

[Another footnote, this one about verse structure. Did JRRT have W.B. Yeats’ early (1888) “The Lake Isle of Innisfree” in the back of his mind with that last line?

Here’s the last stanza of Yeats’ poem:

“I will arise and go now, for always night and day

I hear lake water lapping with low sounds by the shore;

While I stand on the roadway, or on the pavements grey,

I hear it in the deep heart’s core.”

In this poem, Yeats weights the end of each stanza both by using a shorter line and by ending with a series of one-syllable words, which slow things to a stop: deep…heart’s…core. JRRT does the same thing with one-syllable words here: grey…sea’s…mouth.]

The next part of the ballad stanza repeats, in a variation, the earlier motif: what a wonderful person the murdered earl was.

“He was a braw gallant,

And he played at the glove;

And the bonny Earl of Murray,

He was the Queen’s true love.”

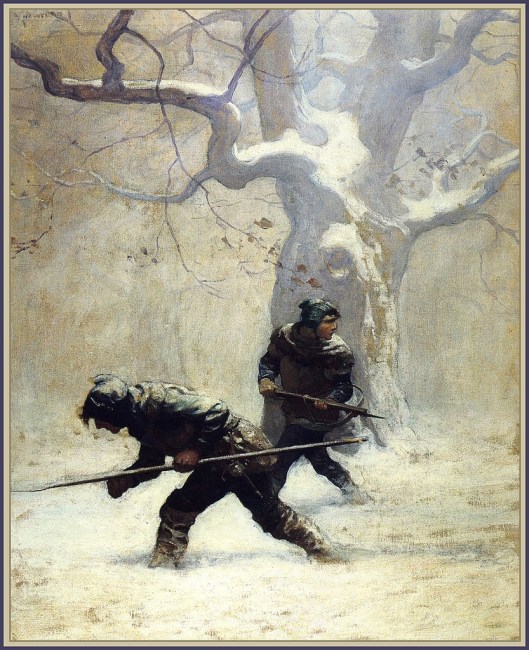

A final piece of glossing. Elizabethans used gloves as a love-present,

suggesting that the last two lines have more than a rhetorical meaning. Historically, James VI’s queen was Anne of Denmark—

was this the real reason why the historical James didn’t seem to be interested in punishing Huntly?

We then have a repetition of the earlier lines:

“O lang will his lady

Lok frae the Castle Doune

Ere she see the Earl o’ Moray

Come soundin’ through the toun.”

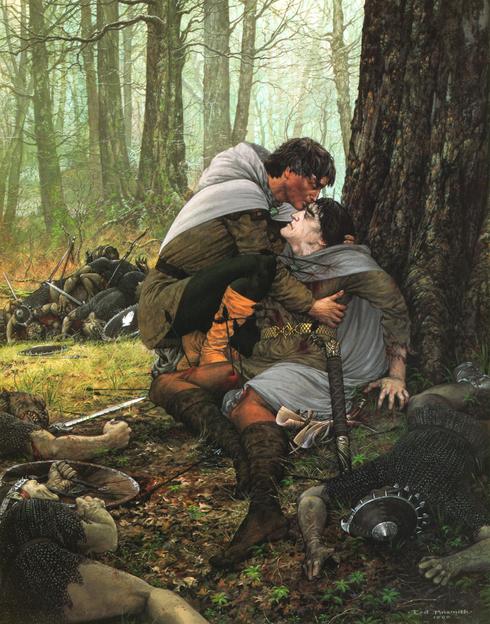

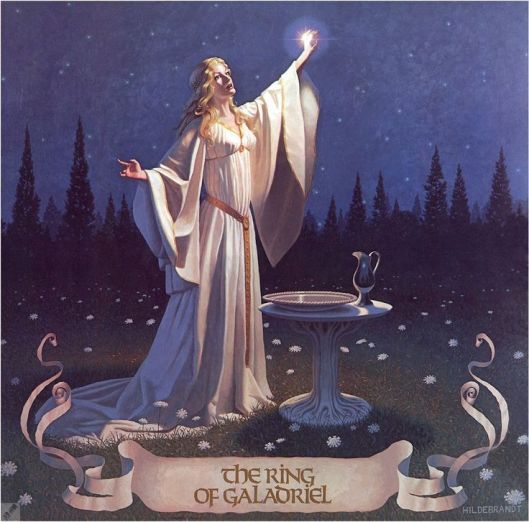

And, with these, the ballad ends, our last image being that of the lady on the castle wall, looking for someone who will never return. This same image, in the form of an inanimate object, waits for Boromir.

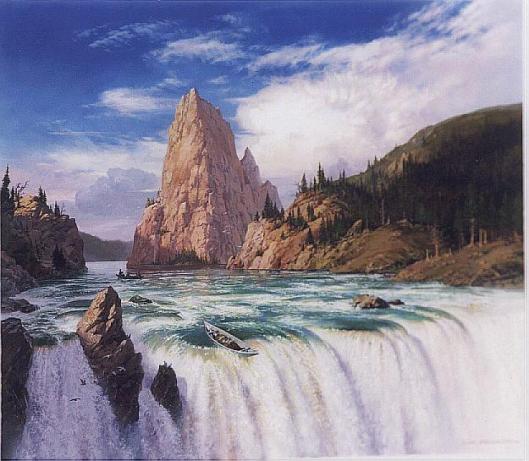

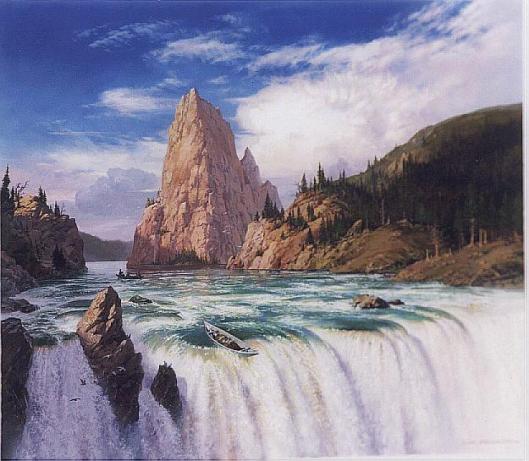

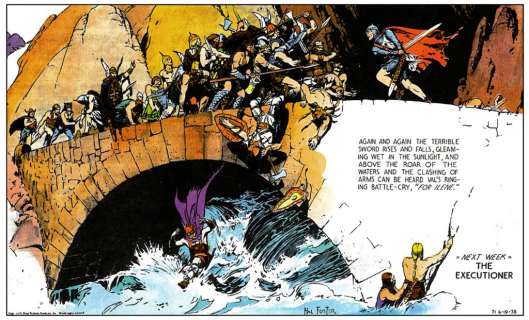

“From the Gate of Kings the North Wind rides, and past the roaring falls;

And clear and cold about the tower its loud horn calls.

‘What news from the North, O mighty wind, do you bring to me today?

What news of Boromir the Bold? For he is long away.’

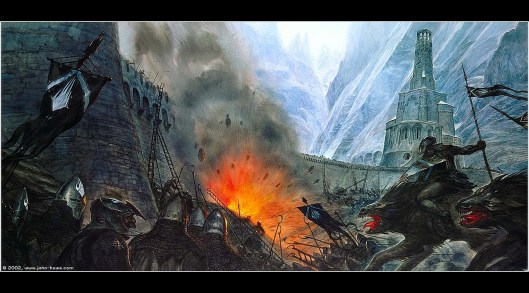

‘Beneath Amon Hen I heard his cry. There many foes he fought,

His cloven shield, his broken sword, they to the water brought.

His head so proud, his face so fair, his limbs they laid to rest;

And Rauros, golden Rauros, bore him upon its breast.’

‘O Boromir! The Tower of Guard shall ever northward gaze

To Rauros, golden Rauros-falls, until the end of days.’ “

Putting the various elements together, we might see this kind of lament as going something like this:

- a speaker appeals to a mass audience of some sort (Scotland/Winds)

- that speaker reveals that something is wrong (Stewart is dead/Boromir is missing)

- he/she can then describe what that is in some way (Stewart was murdered/Boromir has died fighting)

- speaker may describe the fine qualities of the person lamented (Stewart as jouster, lover, kingly/Boromir as tall, fair, died fighting)

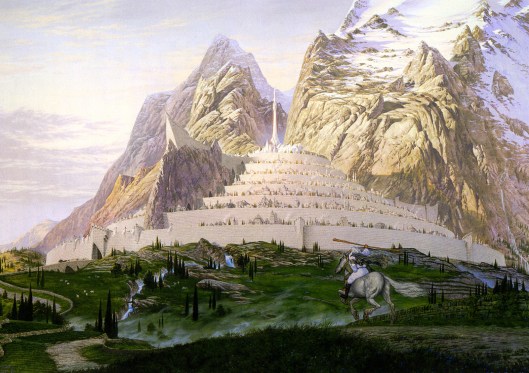

- those who lament cannot be consoled—or perhaps refuse to be (lady on wall of Doune/Tower of Guard=Minas Tirith)

Using this suggested model, can you think of other laments, both in Tolkien or otherwhere which match it?

Thanks, as always, for reading.

MTCIDC

CD

to approach closer and closer until:

to approach closer and closer until: