Tags

British Museum, culture, elections, farthing, feudalism, Government, Hobbitry-in-arms, Hobbits, Louvre, Maps, Mathom-house, Mayor, Michel Delving, Middle-earth, museums, police, Postmen, Sharkey, Shire, Shire-moot, Shire-muster, Shirriffs, Thain, The Hobbit, The Lord of the Rings, The Scouring of the Shire, thegn, Tolkien, vassal, Vatican, voting, White Downs, Witch-King of Angmar

Welcome, dear readers, as always.

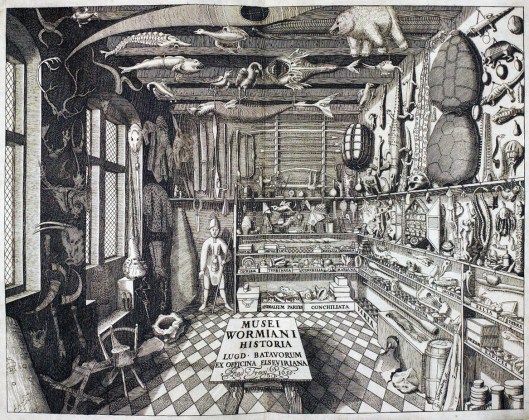

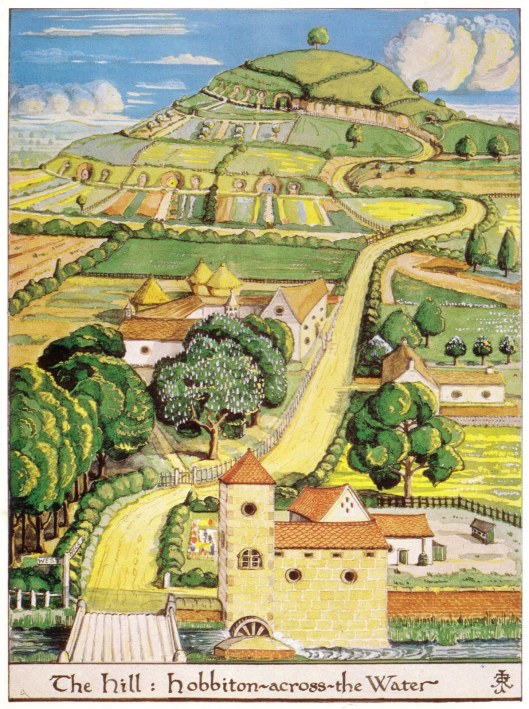

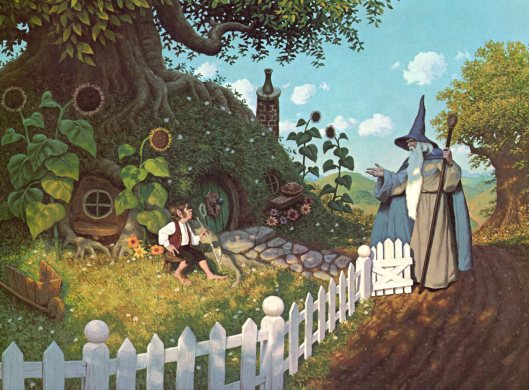

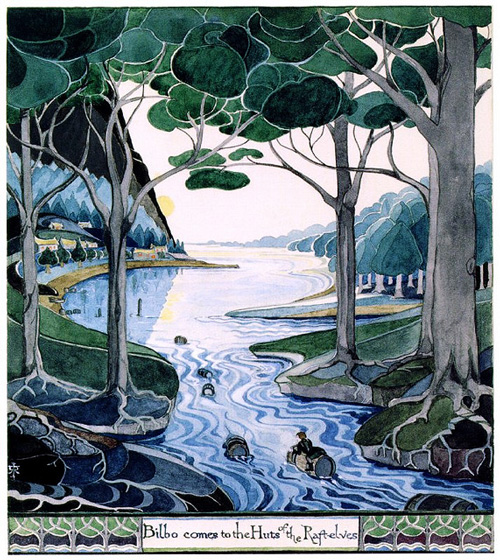

In our last post (well, next-to-last–the last was on circuses), we talked about museums and Mathom-houses and, thinking that the Shire had a museum, made us wonder about what we might call “Shire culture” in general. What is it which makes the Shire the Shire?

To go about answering that, we tried to think of a model. Could we imagine ourselves doing a tourist brochure? A wiki article? And where would we begin?

Suppose, we thought, we begin with the outermost shell, rather as in our world: the government.

The first ten pages of the Prologue to The Lord of the Rings contain a good deal of information about hobbits and their homeland, with many other details to be gleaned from the main body of the text and the appendices and some from The Hobbit. There is undoubtedly more yet to be found in several of the subsidiary volumes, but we decided that, to make this a series of readable posts and not a small encyclopedia, we would stick to the two main works.

With all of that material to help us, all we needed was an entry point—and, almost immediately, we decided that we could begin where we left off, with that very museum, which originally attracted us because it stood out as something one would expect from a much more organized state, rather than from what, on the whole, appears to be such a rural and decentralized place.

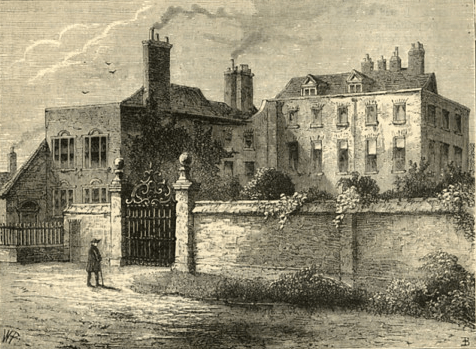

After all, museums, as we have discussed, are a relatively recent invention in the west and public museums are even newer (the first state-sponsored museum in Britain, for example, only dates from the 1750s). Since our last posting, we’ve done a bit more research and, with one or two possible exceptions, it seems that public museums only begin to appear at all from the second half of the 17th century. (A quick and useful reference may be found at: https://museu.ms) Even so, such places have a good deal to say about a culture:

- that it values elements of its past, both historical and artistic, enough that it is willing to collect and preserve them

- that it believes that such elements should then be put upon public display (the why of that might include: to use for educational purposes—which assumes that the past has things to teach the present; to provide aesthetic pleasure; even to show the wealth and power of a state which has such a history and such artists)

- that it is willing to provide space, at the public expense, to house and display such things

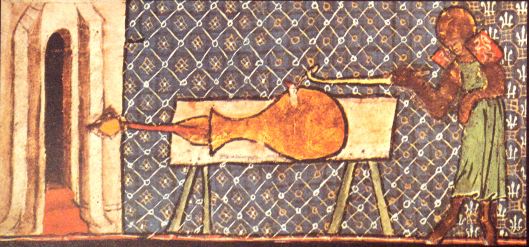

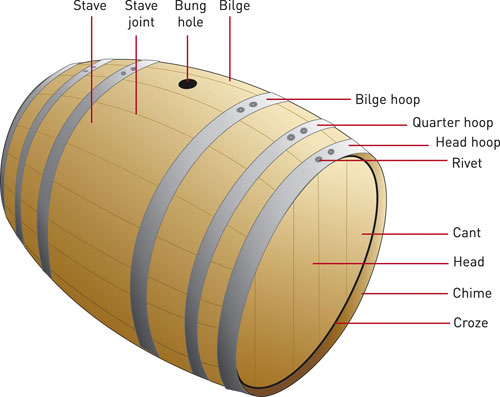

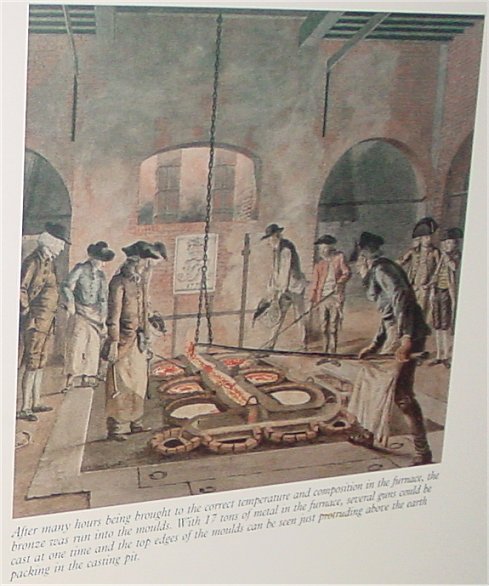

The Mathom-house is hardly, from JRRT’s description, the equivalent of the British Museum

or the Louvre

or the Vatican

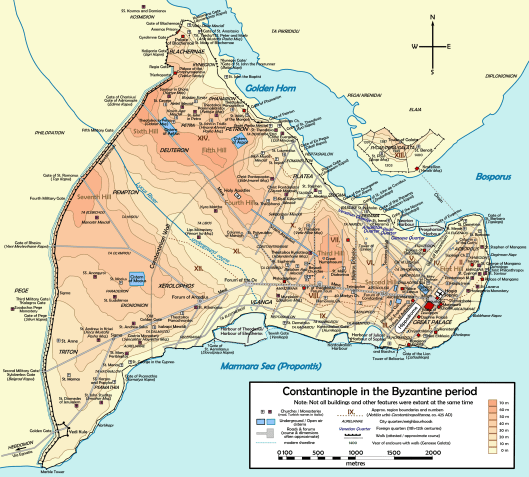

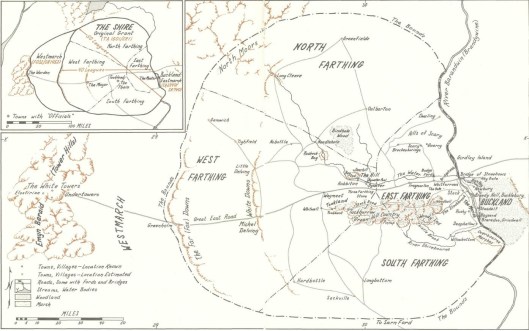

or any of the other thousand wonderful museums around the world, big or small. And yet it is there and in the closest thing to a capital which the Shire has to offer, Michel Delving. It is only the closest thing because the Shire has almost no formal governing structure.

As the Prologue says:

“The Shire at this time had hardly any ‘government’. Families for the most part managed their own affairs…”

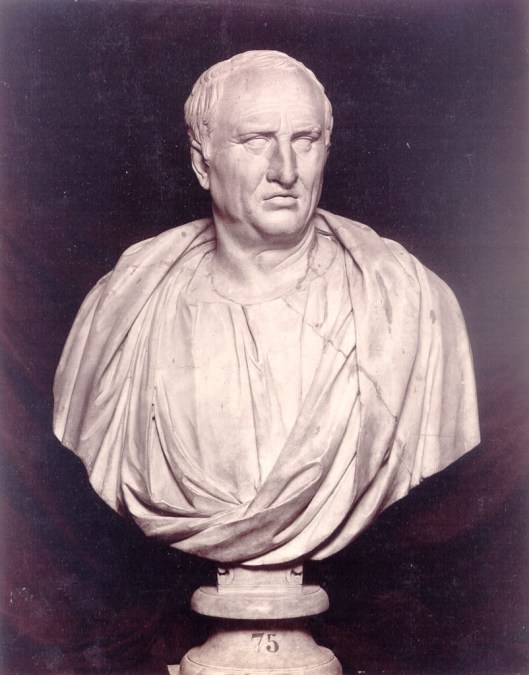

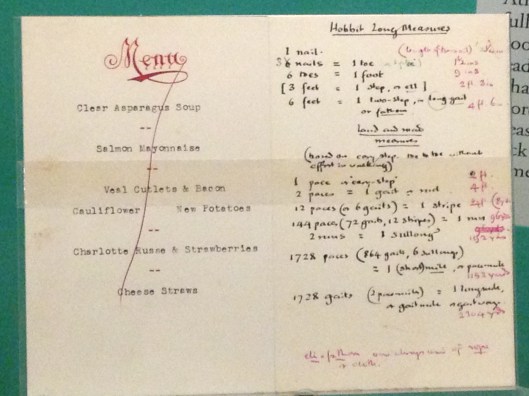

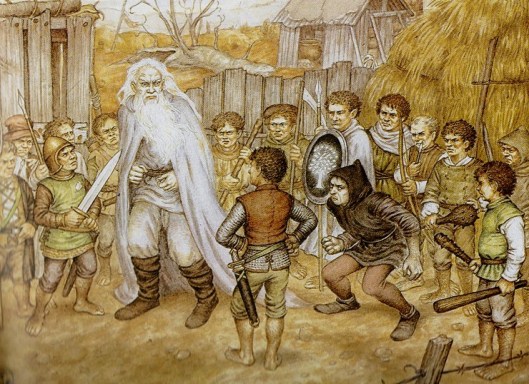

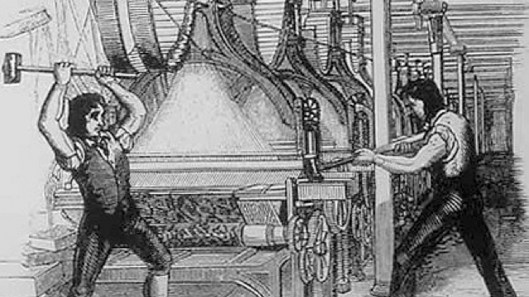

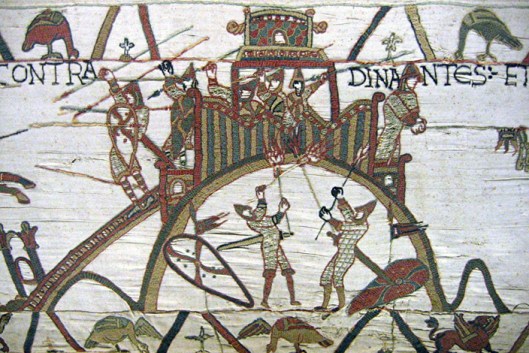

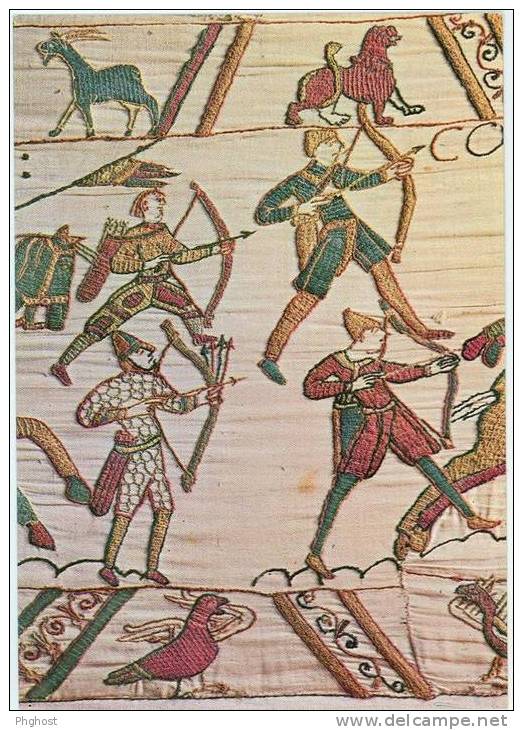

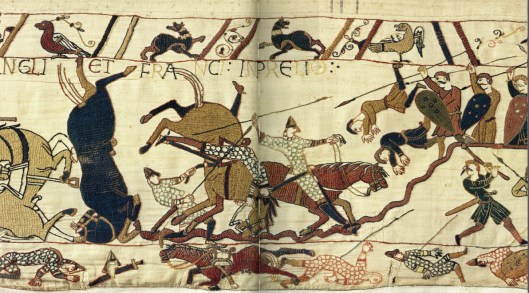

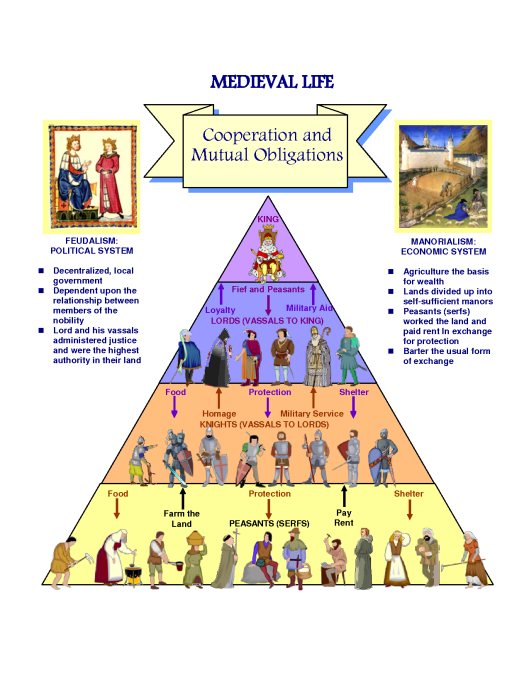

Originally, as the Prologue tells us, the Hobbits had moved into the land which would become the Shire with the permission of the high king of the North Kingdom, at Fornost. When the last king and his kingdom had fallen to the Witch King of Angmar, the Hobbits replaced him with a “Thain” (actually an Old English word for, among other things, a “vassal”—that is, one who acts as a subordinate—in a feudal system, this might imply that the person has received land from someone higher on the social scale in return for taxes and/or military service). Here’s a thegn (Old English spelling) as a warrior.

By the time of The Hobbit, this office had dwindled, but not quite disappeared:

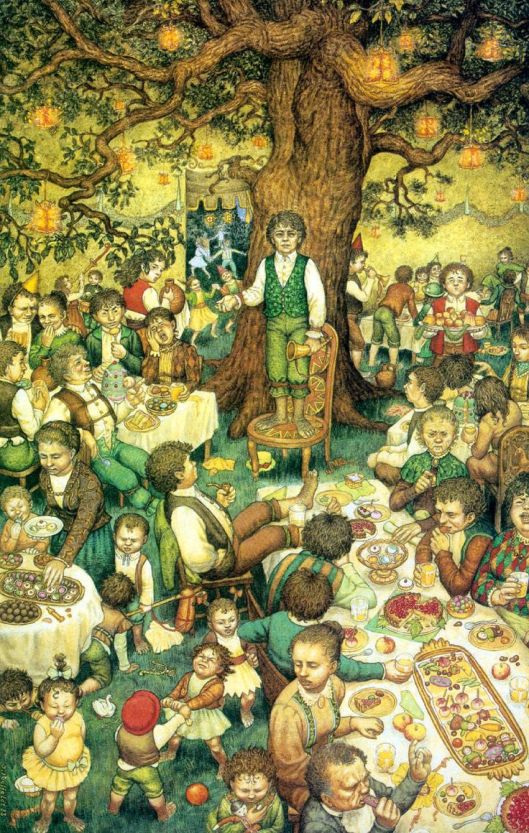

“The Thain was the master of the Shire-moot, and captain of the Shire-muster and the Hobbitry-in-arms, but as muster and moot were only held in times of emergency, which no longer occurred, the Thainship had ceased to be more than a nominal dignity.”

In fact,

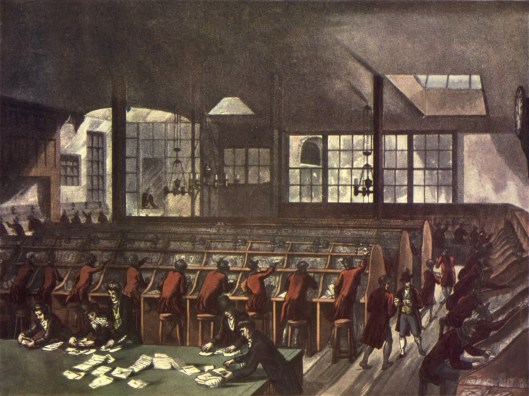

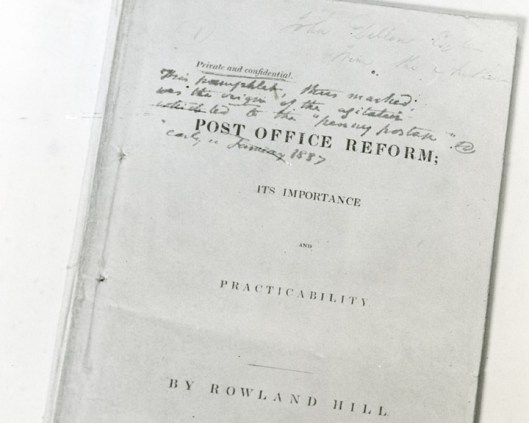

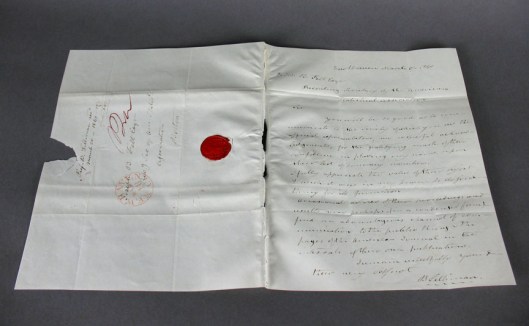

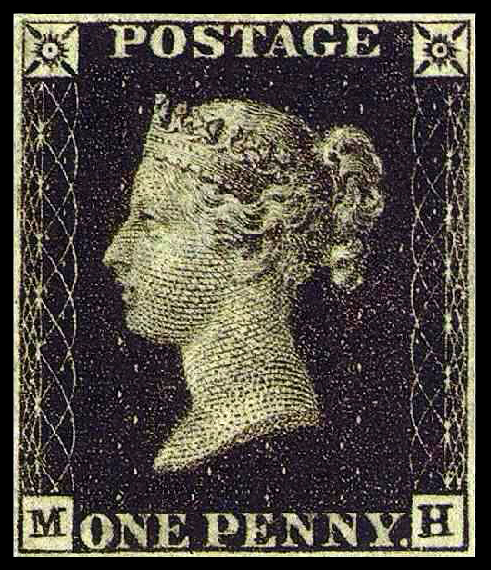

“The only real official in the Shire at this date was the Mayor of Michel Delving (or of the Shire), who was elected every seven years at the Free Fair on the White Downs at the Lithe, that is at Mid-summer. As mayor almost his only duty was to preside at banquets, given on the Shire-holidays, which occurred at frequent intervals. But the offices of Postmaster and First Shirriff were attached to the mayoralty, so that he managed both the Messenger Service and the Watch. These were the only Shire-services, and the Messengers were the most numerous, and much the busier of the two. By no means all Hobbits were lettered, but those who were wrote constantly to all their friends (and a selection of their relations) who lived further off than an afternoon’s walk.

The Shirriffs was the name that the Hobbits gave to their police, or the nearest equivalent that they possessed…they were in practice rather haywards than policemen, more concerned with the strayings of beasts than of people. There were in all the Shire only twelve of them, three in each Farthing, for Inside Work. A rather large body, varying at need, was employed to ‘beat the bounds’, and to see that Outsiders of any kind, great or small, did not make themselves a nuisance.”

This gives us the whole of the top level of Shire culture, the public face: a vestigial Thain (representative of the long-gone King), a figurehead Mayor, a postal service, and a tiny police force/border guard.

And how does any of these hold office?

The Thain, as we know, is hereditary.

The Mayor is, as quoted above, elected—although we have no idea of the process. Does one vote by town? By Farthing? Or is there simply a kind of country-wide method? We also have no idea of suffrage: who has the vote in the Shire? Is it general (England had general suffrage by the time JRRT was writing The Hobbit, all men over 21 by 1918, some women—householders over the age of 30—having been included in elections in 1918, women in general over 21 in 1928)? Or is it the older “only property-holders” method? Or are there “hereditary electors” who do the choosing? (As CD have just gone through an election here in the US, all of these questions, as you can imagine, are fresh in our minds!)

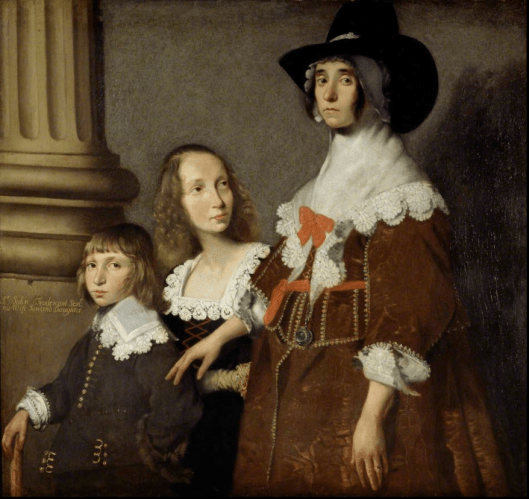

The “postmen” (our word) are, so far as we can tell, a mystery, both as to who they are or how they gain their employment.

Shirriffs appear to be volunteers, as we learn in “The Scouring of the Shire”, when Sam talks to Robin Smallburrow, who says “You know how I went for a Shirriff seven years ago, before any of this began.”

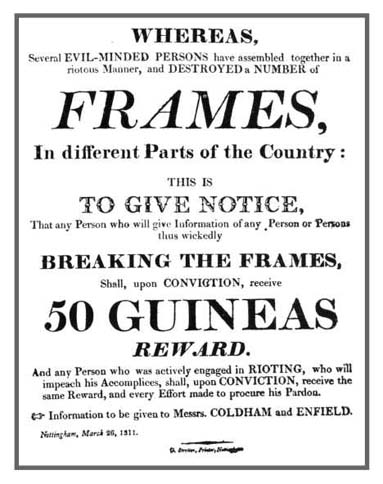

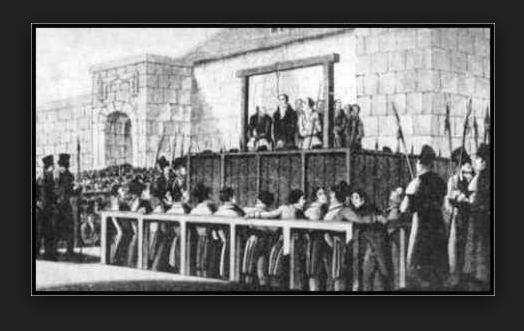

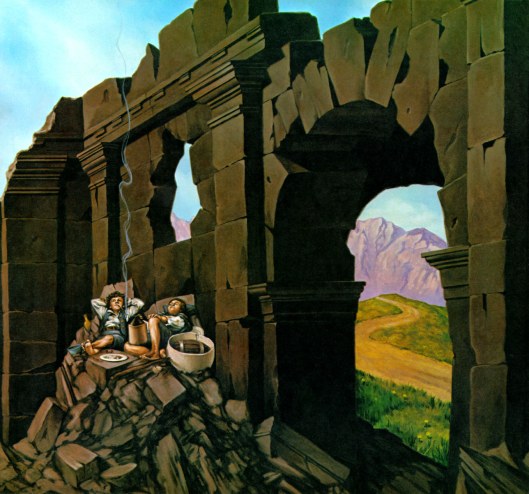

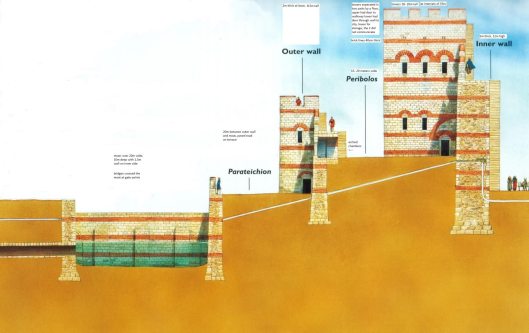

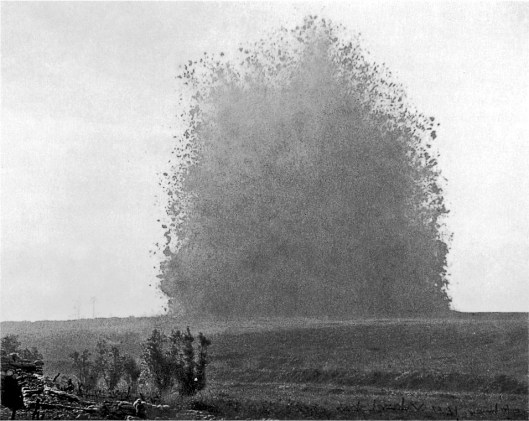

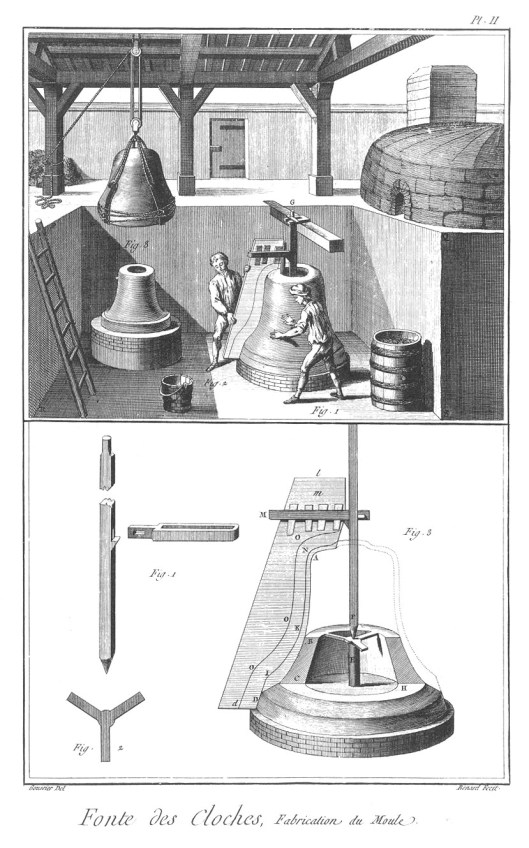

There being so little in the way of government, are there any public buildings except for the Mathom-house? If there are, we have yet to locate them. It’s striking that, when “Sharkey” takes over the Shire, he sets up a number of such places, but neither government buildings nor museums, instead, they are tokens of a police state: barracks and watch houses, dens reminding us of something which JRRT would have seen all too much of in newspapers and magazines, as well as newsreels as he worked on the early stages of The Lord of Rings:

(More on Sharkey and the takeover in a future posting!)

Considering that there is a small policing force, as well as a kind of postal institution, we looked for another government department: the Internal Revenue Service. After all, we pay for our police and used to pay for postage stamps, back in pre-internet days, and we pay for public museums, too: how does it work in the Shire? The simple answer is, we don’t know. In fact, we don’t really know much about how the economy works in general. And that will be the subject of our next posting.

Thanks, as always, for reading!

MTCIDC

CD