Tags

Alexander, Dunlendings, elephant, Fantasy, Hannibal, Heffalumps, movies, Mumak, Perseus, Poros, Seleucus, The Lord of the Rings, The War Of the Rohirrim, the-war-of-the-rohrrim, Tolkien, Winnie the Pooh

Welcome, as always, dear readers.

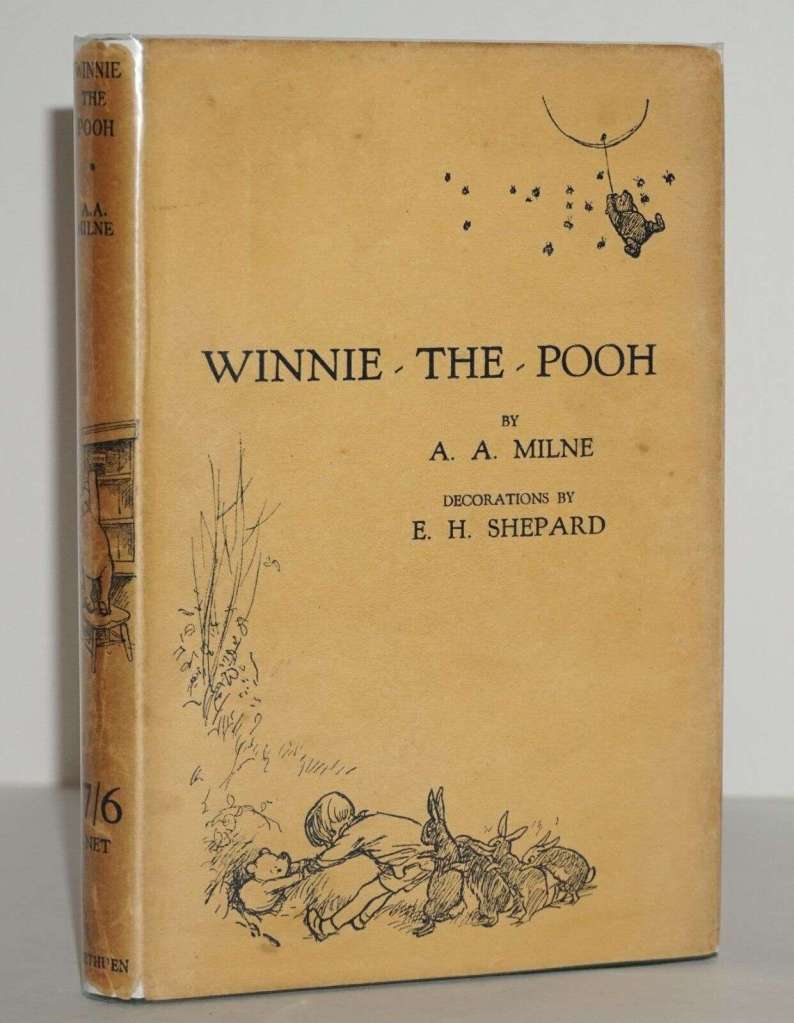

“And then, just as they came to the Six Pine Trees, Pooh looked round to see that nobody else was listening, and said in a very solemn voice:

‘Piglet, I have decided something.’

‘What have you decided, Pooh?’

‘I have decided to catch a Heffalump.’ ” (Winnie-the-Pooh, Chapter V, “In Which Piglet Meets a Heffalump”)

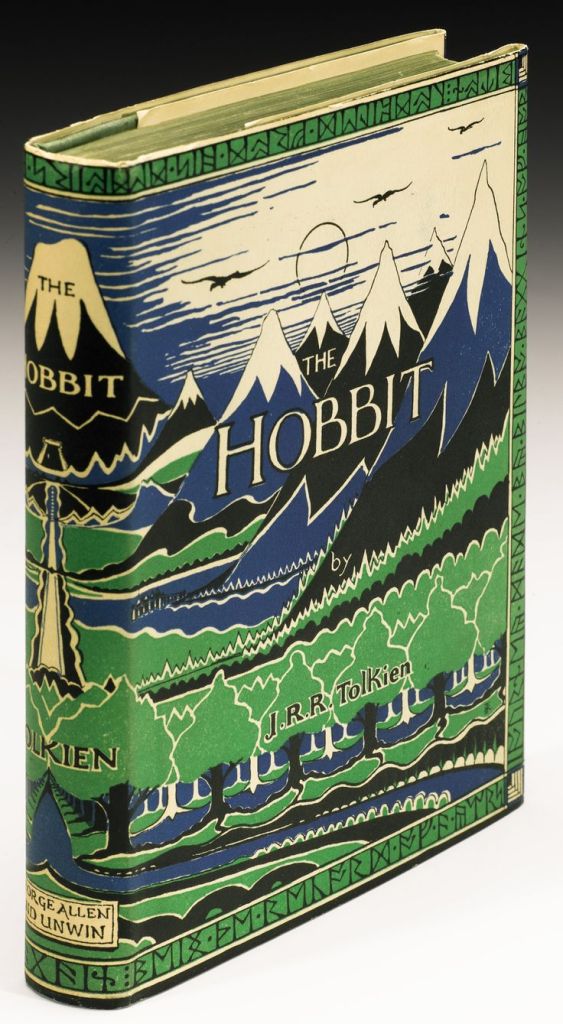

Winnie-the-Pooh has just turned 100,

the book’s birthday being in1926, but the Pooh himself first appeared on Christmas eve, 1925, in the The Evening News.

(For more Poohsiana, including the origins of the character, see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Winnie-the-Pooh )

Although it’s never defined, from the tone of the chapter, I’ve always imagined that a “heffalump” was, in fact, an elephant.

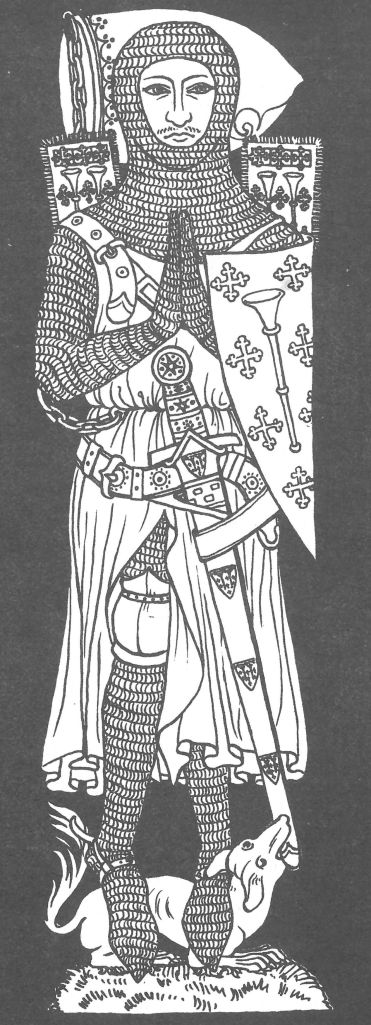

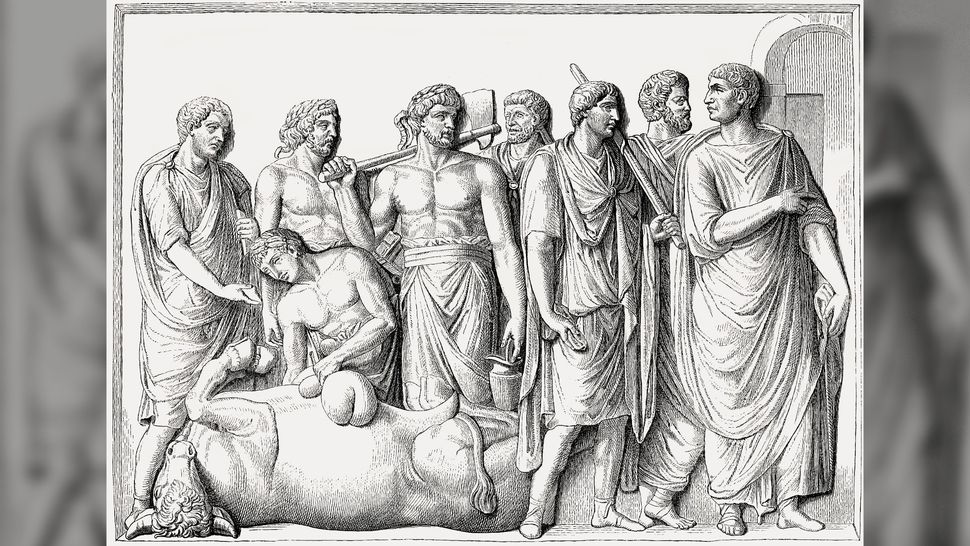

(An elephant and a tradional mortal enemy. This is from the 13th-century Harley MS 3244, in the British Library, which I found at a wonderful medieval site: https://medievalbestiary.info/index.html )

And that elephant reminded me—traditionally, elephants are supposed to have wonderful memories, after all–that I was going to continue my review of the anime The War of the Rohirrim, where, surprisingly, a heffalump—sorry—a mumak—that is, an elephant, appears.

But why?

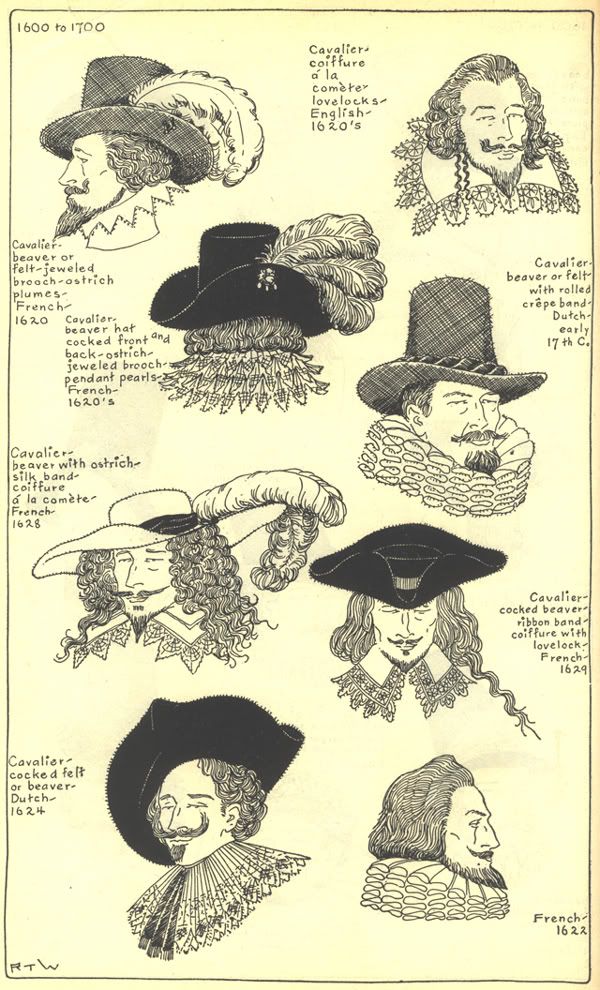

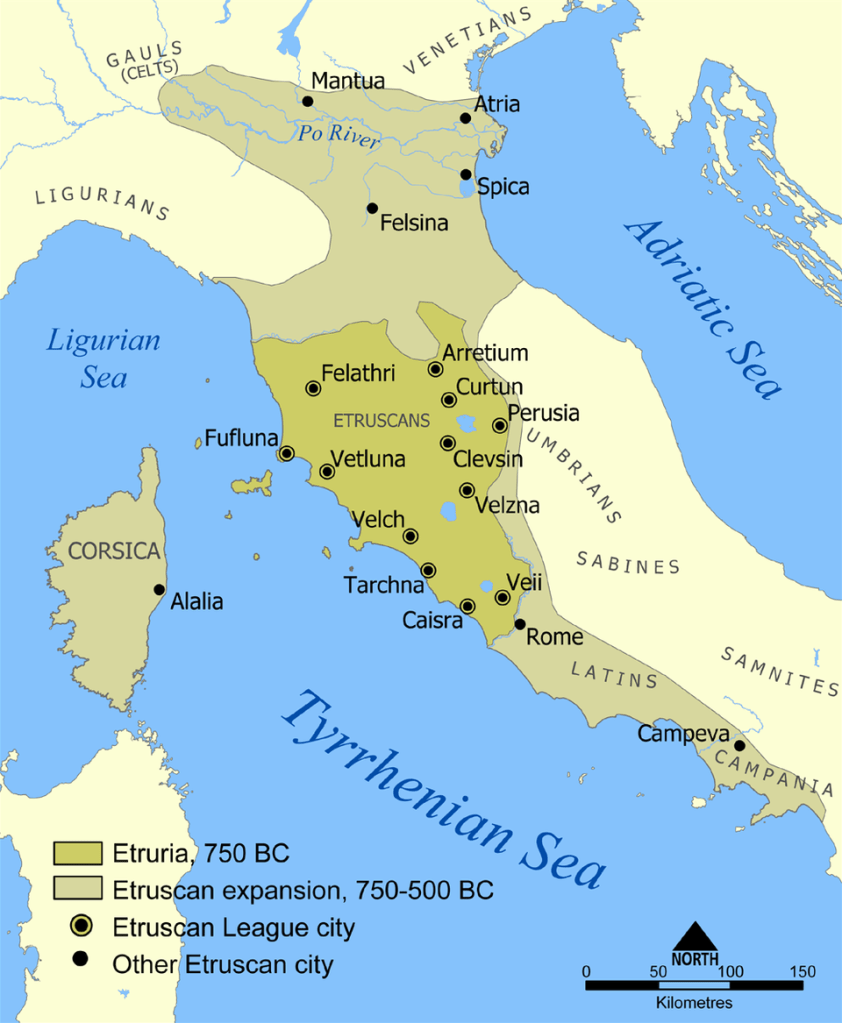

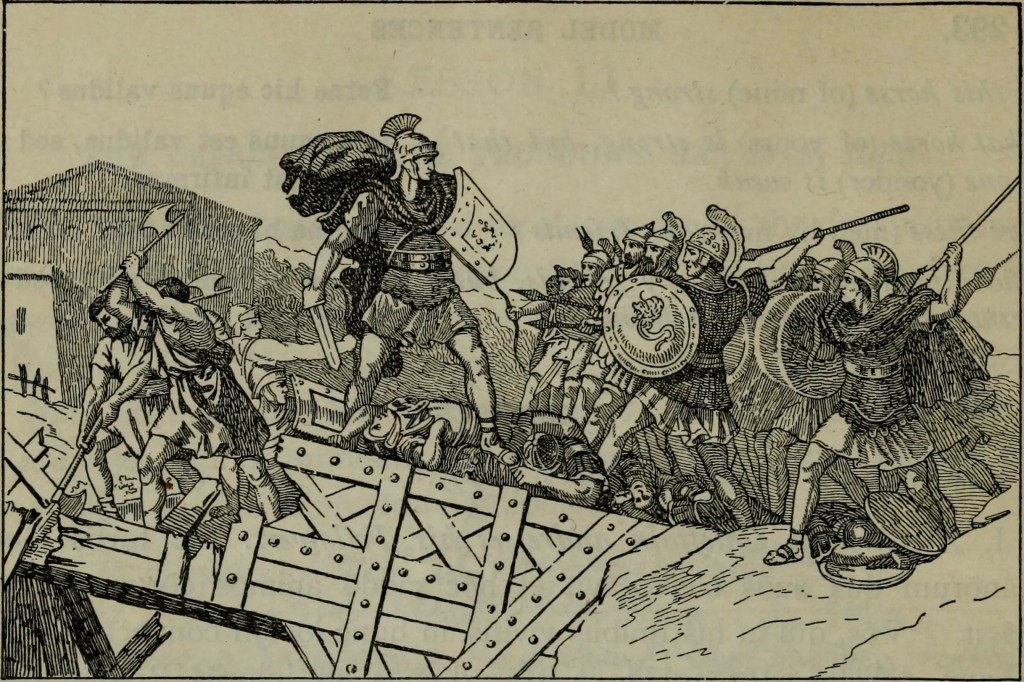

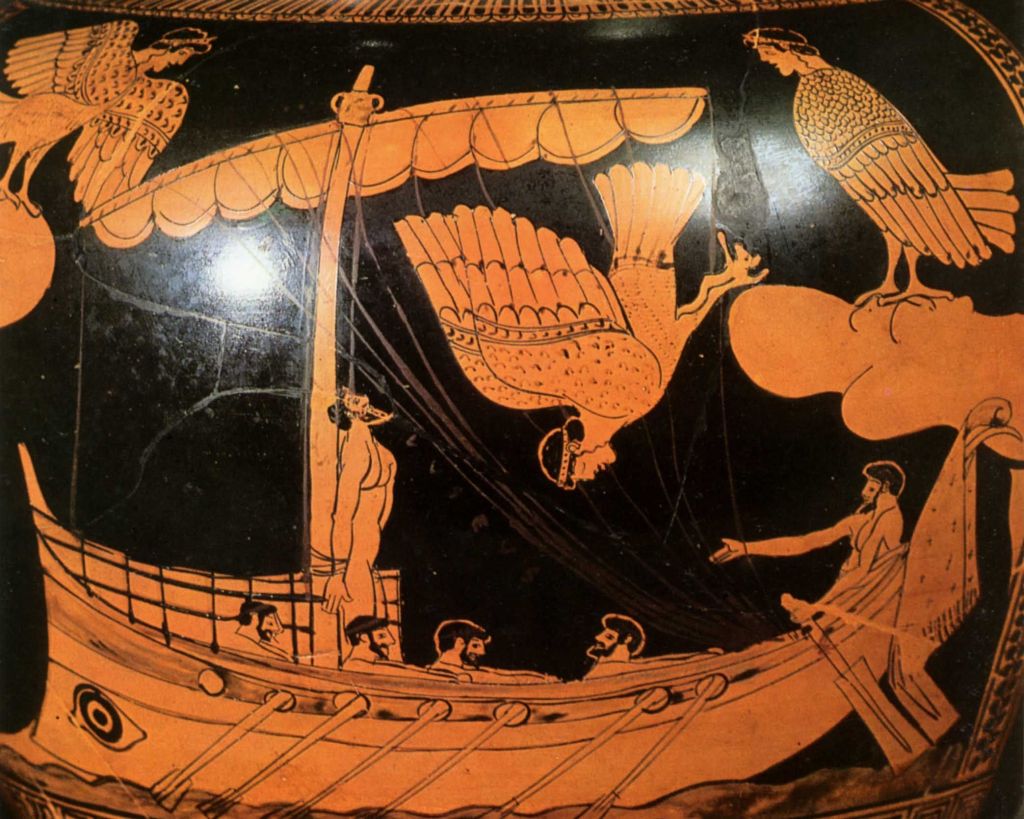

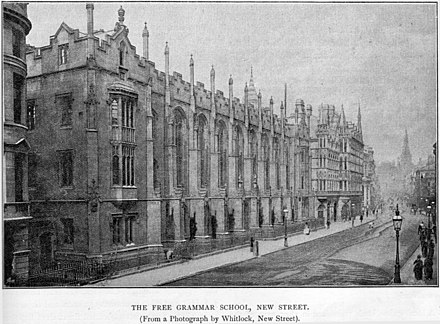

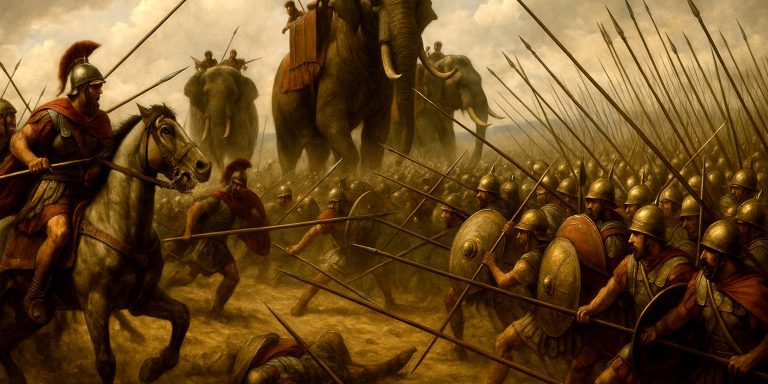

The West first encountered war elephants when Alexander, marching eastwards, came up against the forces of Poros, an Indian king.

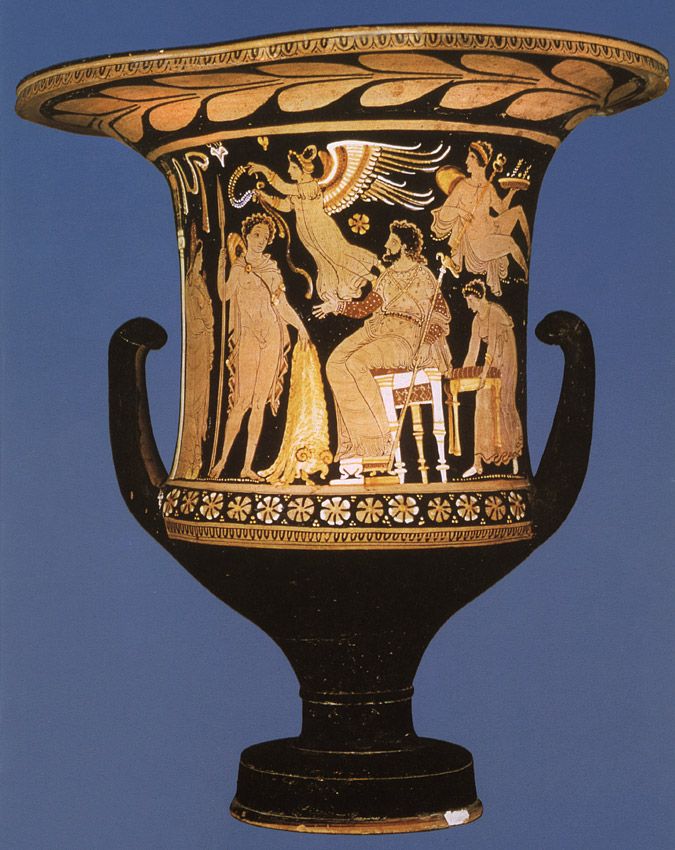

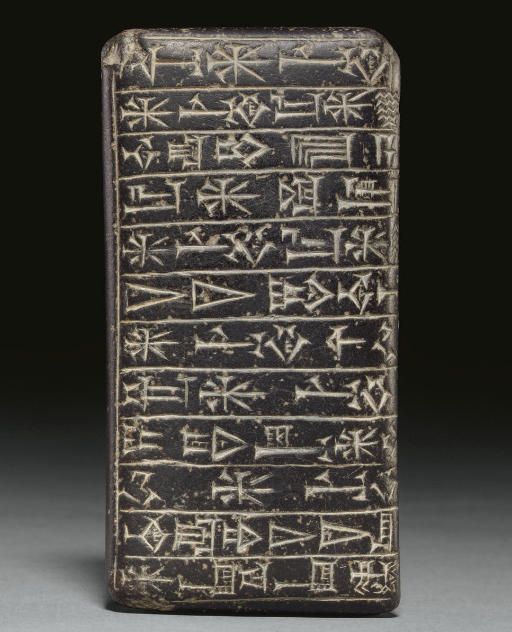

(a Macedonian commemorative coin c.324-3222BC, depicting an elephant-borne Poros. For more on Poros, see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Porus )

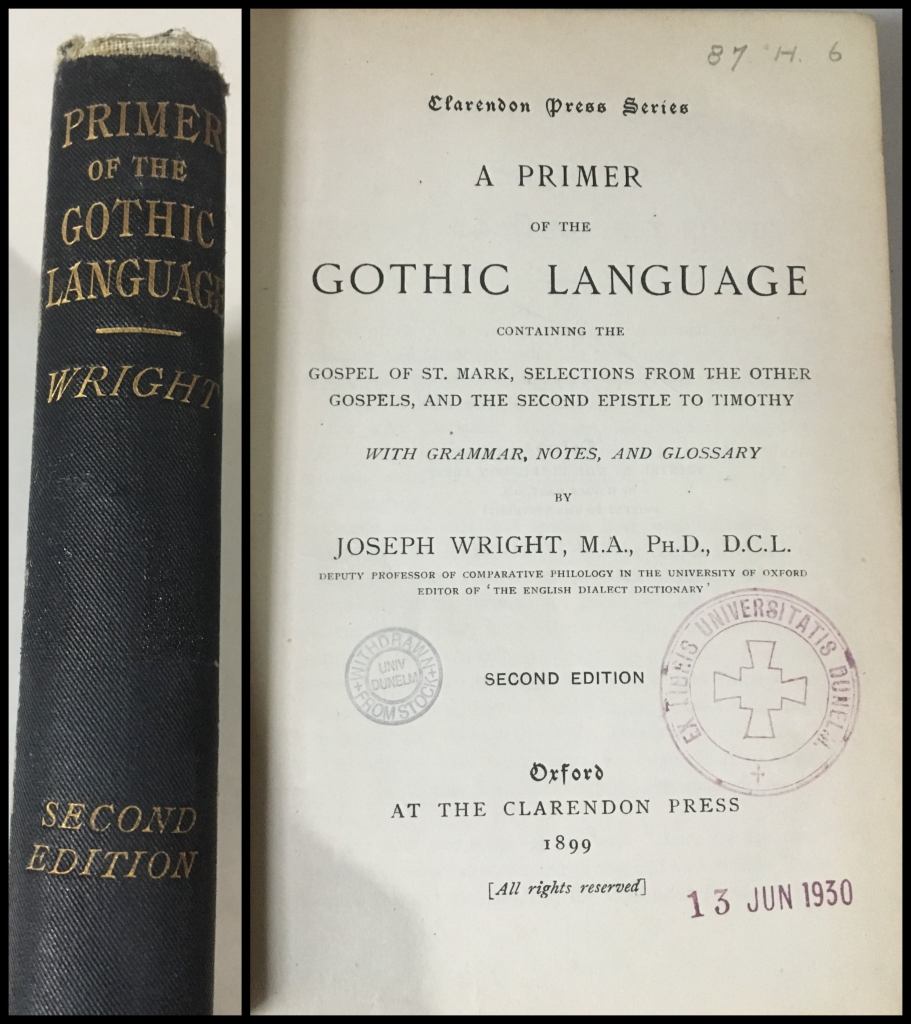

One of Alexander’s generals—and successors—Seleucus, c.358-281BC,

in a treaty with the Indian Mauryan kingdom, received 500 war elephants, which were then employed at the Battle of Ipsus, in 301BC,

during the wars which Alexander’s generals fought among themselves to define who would control various parts of Alexander’s empire.

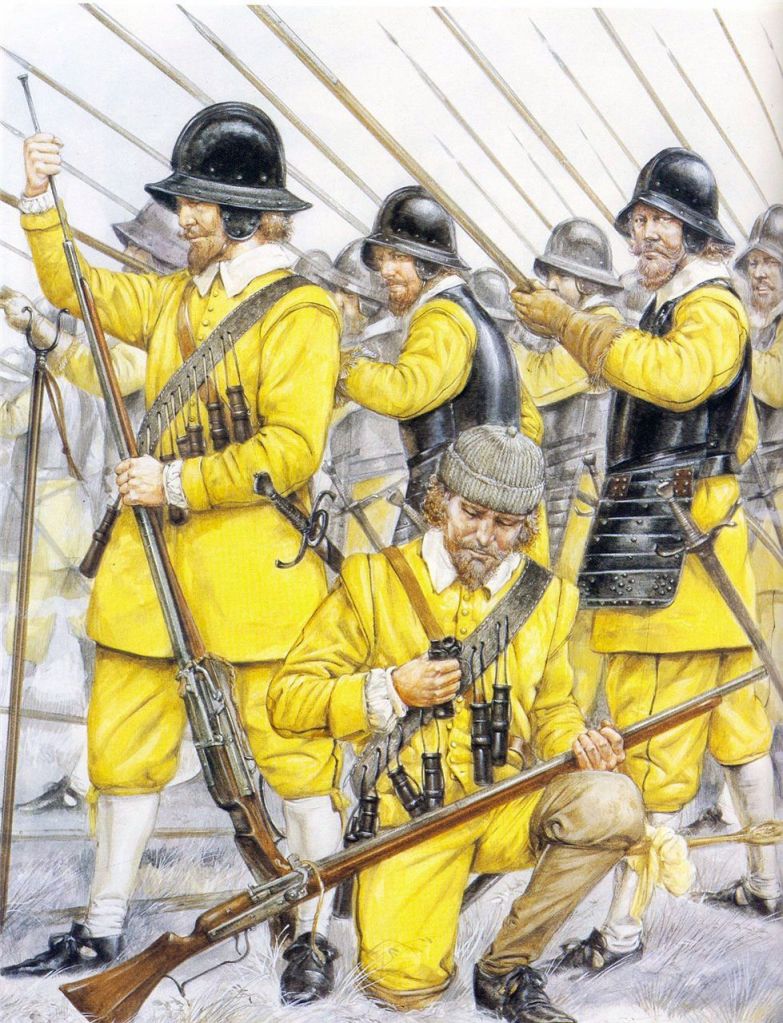

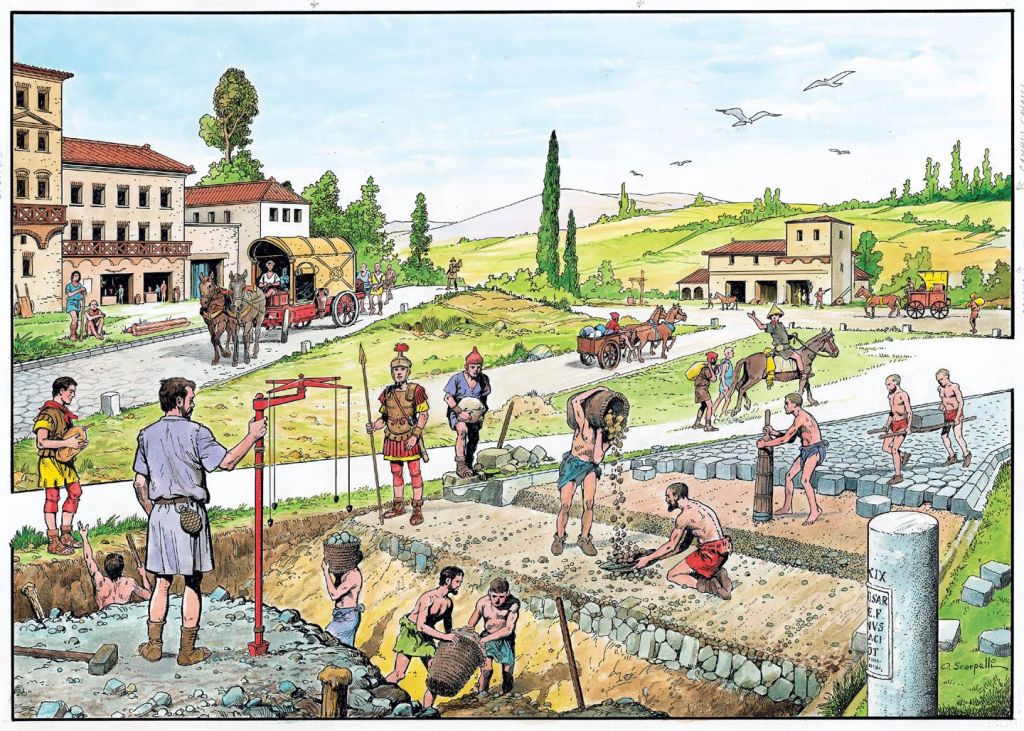

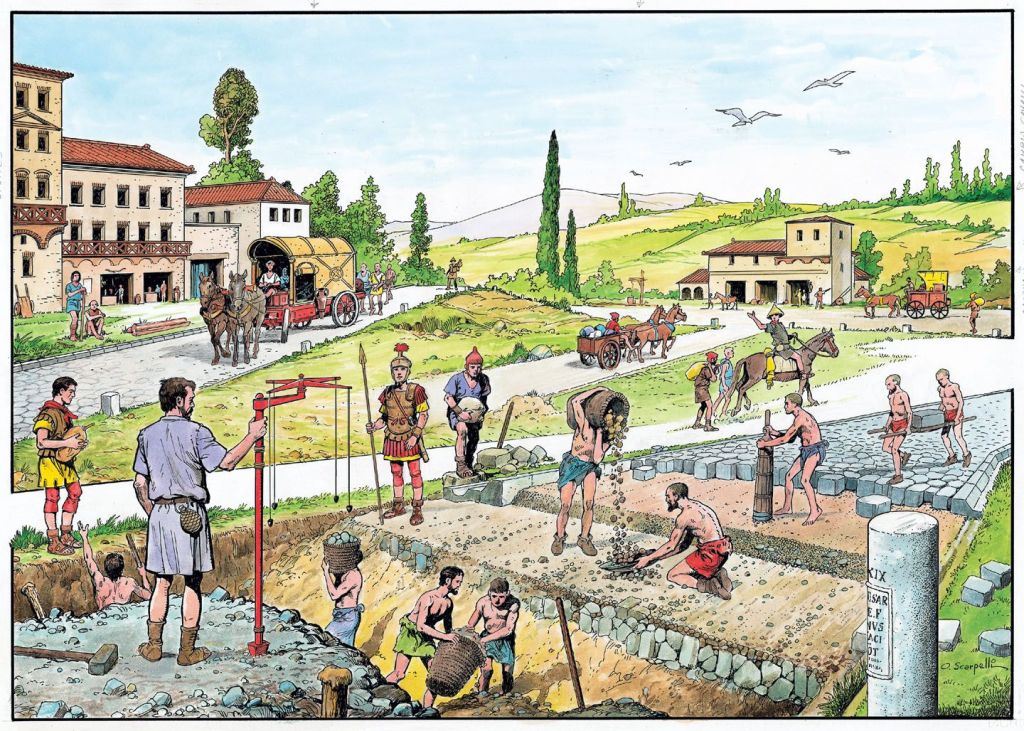

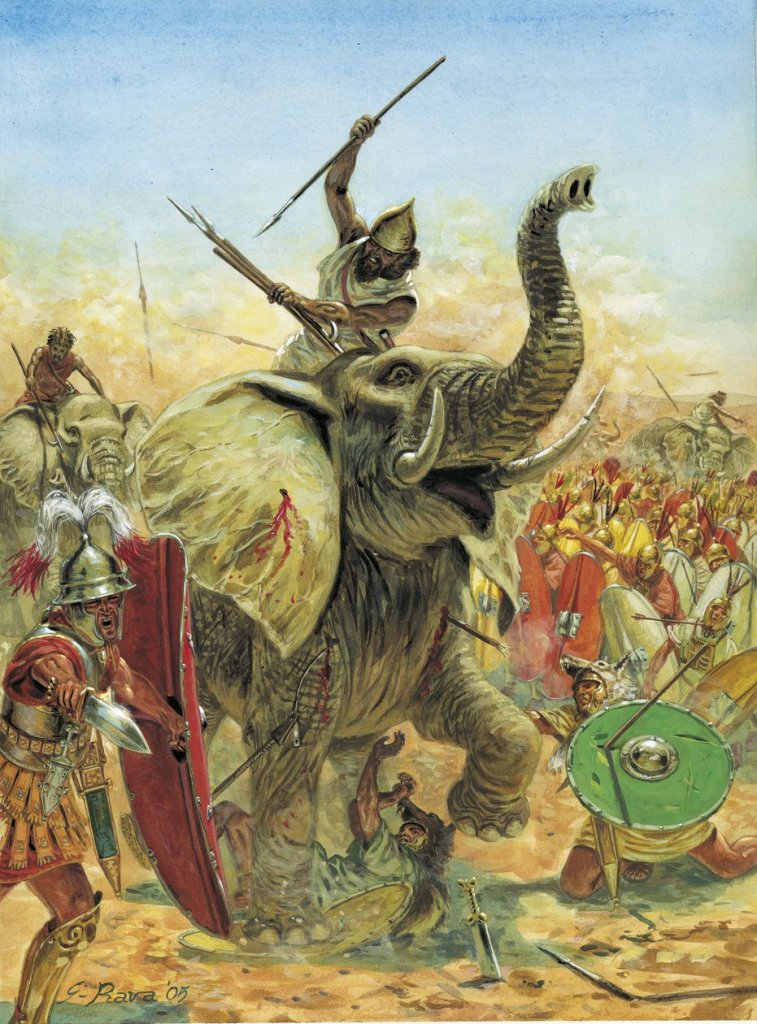

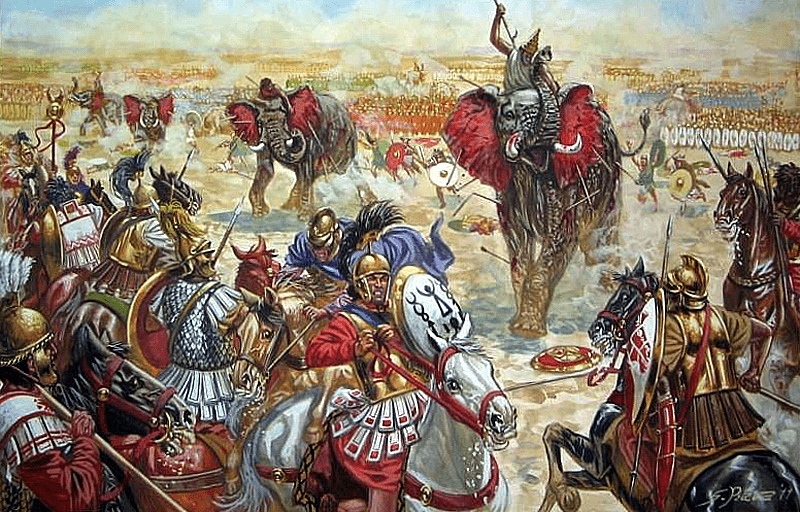

Elephants could be seen as rather like tanks—large, mobile weapons to break enemy lines—

(Peter Dennis)

(Giuseppe Rava)

and would continue to be used in the West at least until the Romans defeated the last Macedonian king, Perseus, at the Battle of Pydna, in 168BC, but saw perhaps their most dramatic use in the wars of Carthage against Rome, particularly in the second war, where the Carthaginian general, Hannibal, invaded Italy by crossing the Alps, bringing a number of elephants with him.

(Angus McBride)

Unfortunately for Hannibal—and his elephants—the Romans had learned to deal with the great beasts and even to turn them back against their owners—

(Peter Dennis)

(for more on war elephants, see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/War_elephant )

Another factor in warfare was the belief that horses are frightened of elephants,

(Giuseppe Rava)

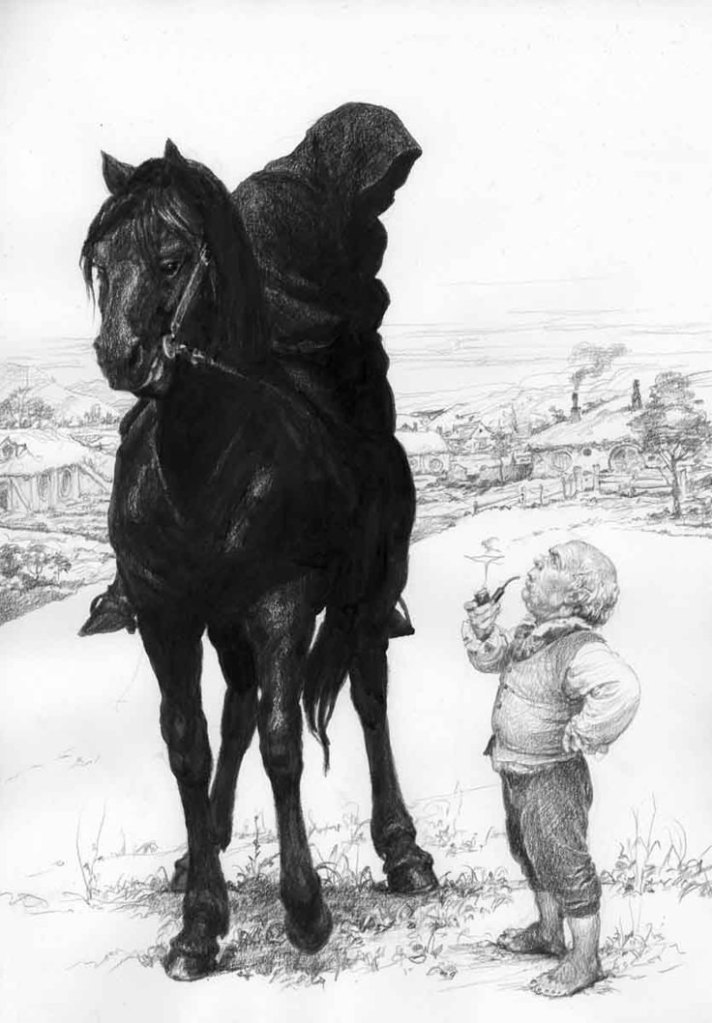

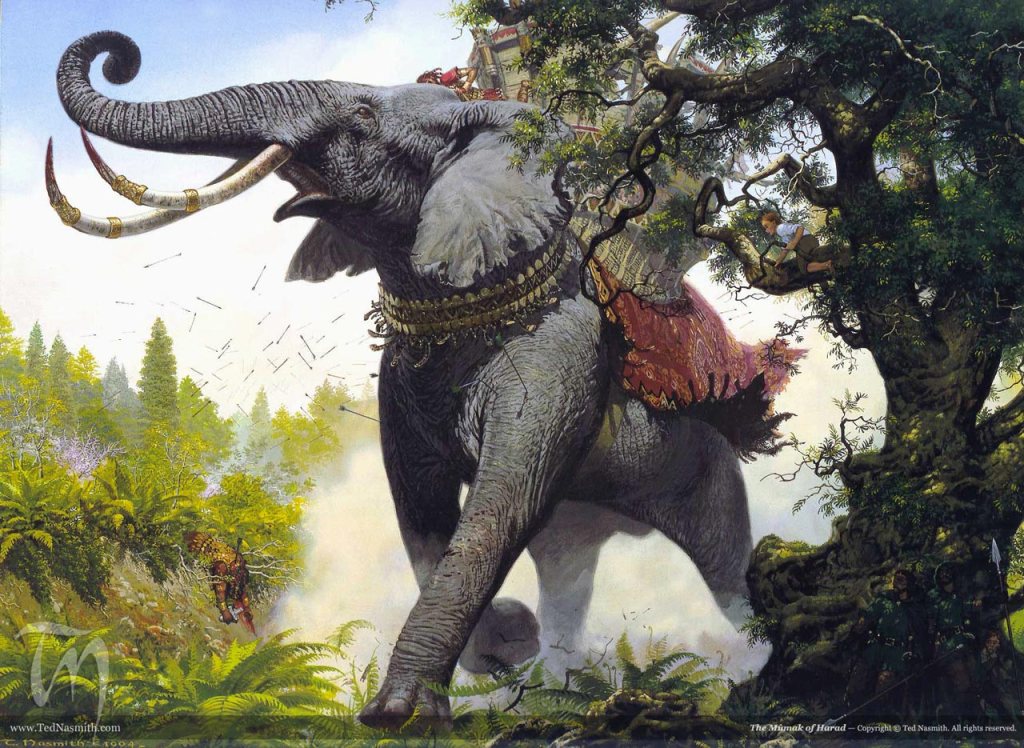

something which even Tolkien mentions—

“But wherever the mumakil came there the horses would not go, but blenched and swerved away…” (The Return of the King, Book Five, Chapter 6, “The Battle of the Pelennor Fields”)

(For more on horses’ potential hippophobia, see: https://iere.org/are-horses-scared-of-elephants/ )

But that is in relation to the allies of Mordor in its attack on Minas Tirith: why is there one of these monsters prominent at the Dunlendings’ attack on Edoras, some 250 years earlier?

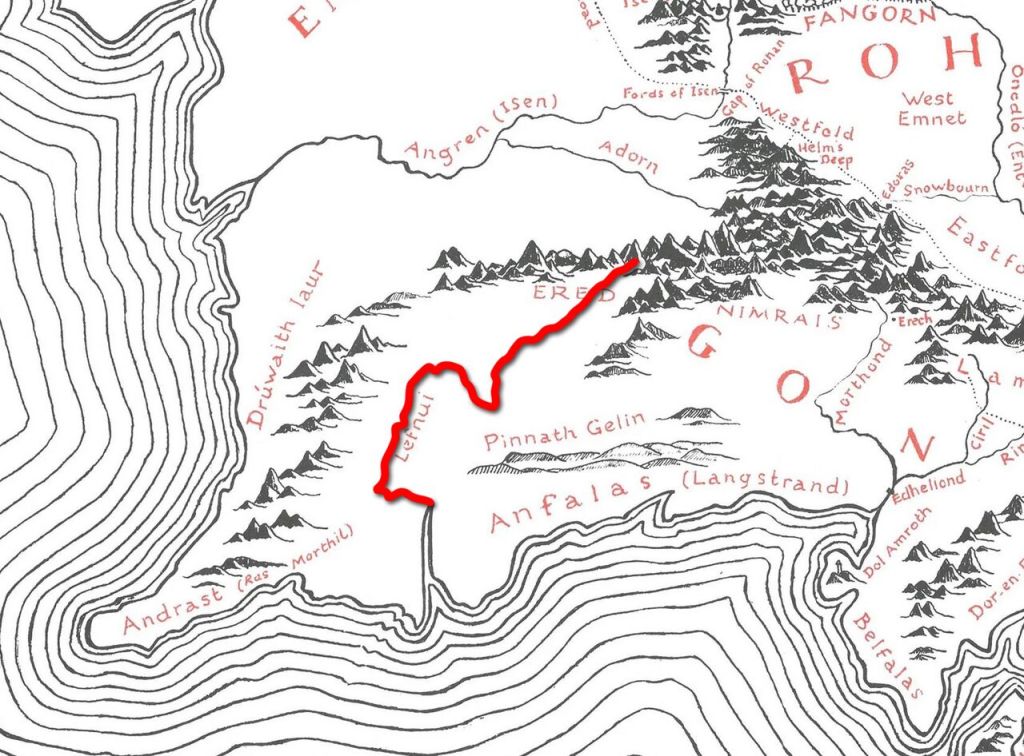

The film’s script-writers seem to be depending upon this passage from Appendix A of The Lord of the Rings:

“Four years later ([TA2758) great troubles came to Rohan, and no help could be sent from Gondor, for three fleets of the Corsairs attacked it and there was war on all its coasts. At the same time Rohan was again invaded from the East, and the Dunlendings seeing their chance came over the Isen and down from Isengard. It was soon known that Wulf was their leader. They were in great force, for they were joined by Enemies of Gondor that landed in the mouths of Lefnui and Isen.” (Appendix II: The House of Eorl)

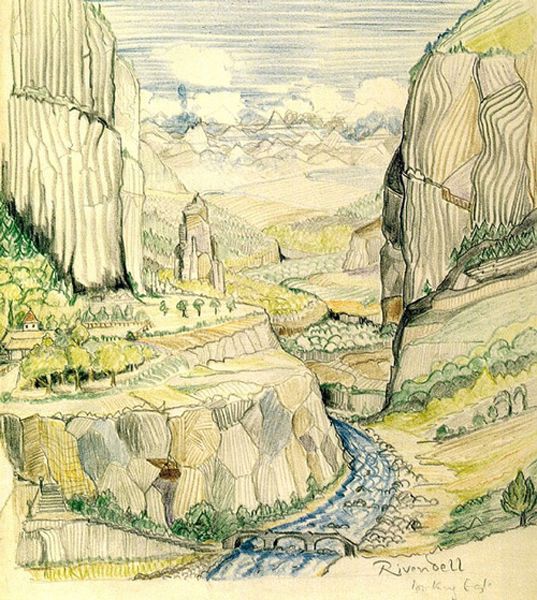

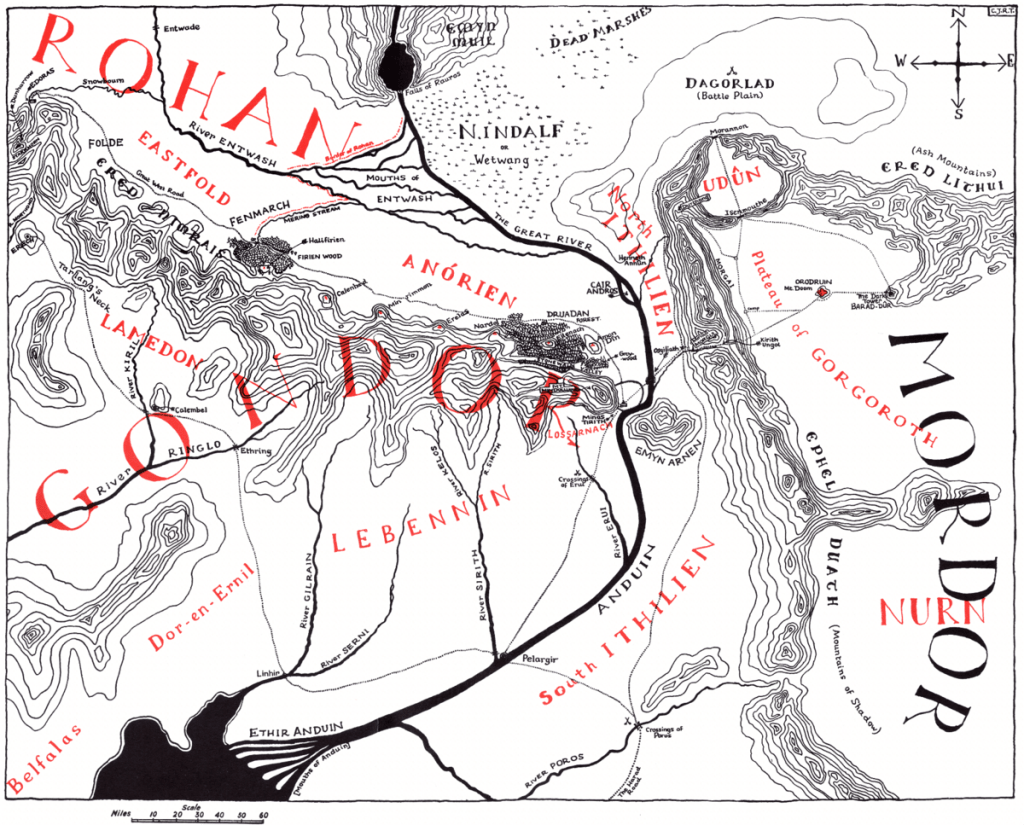

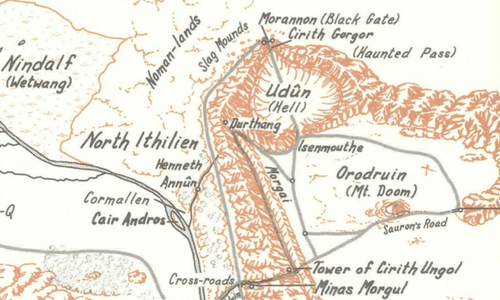

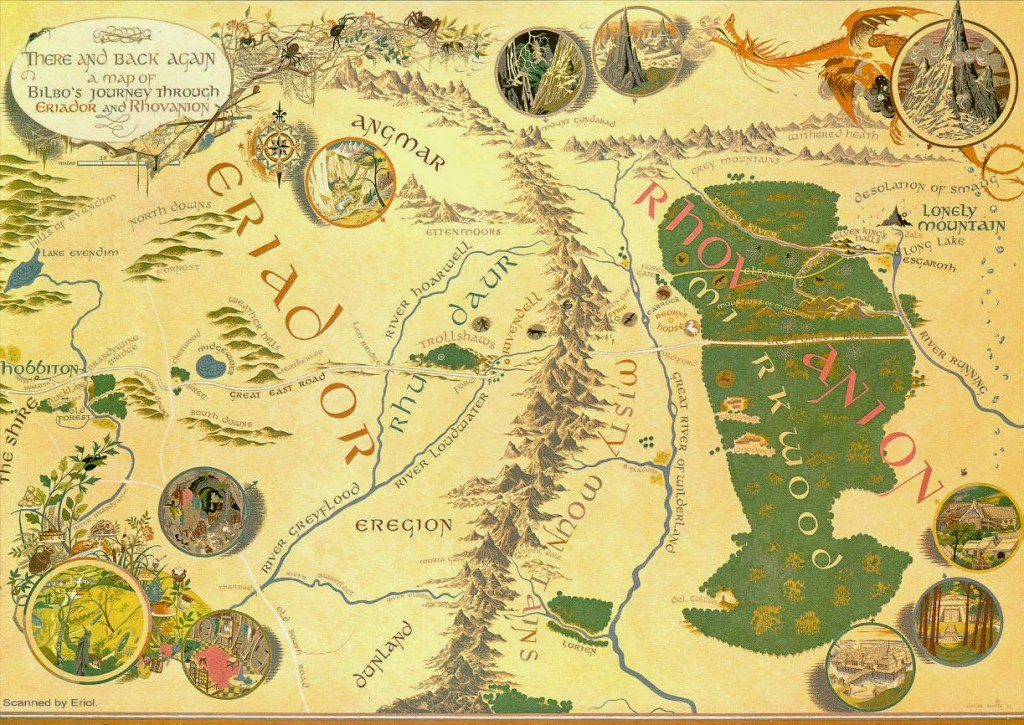

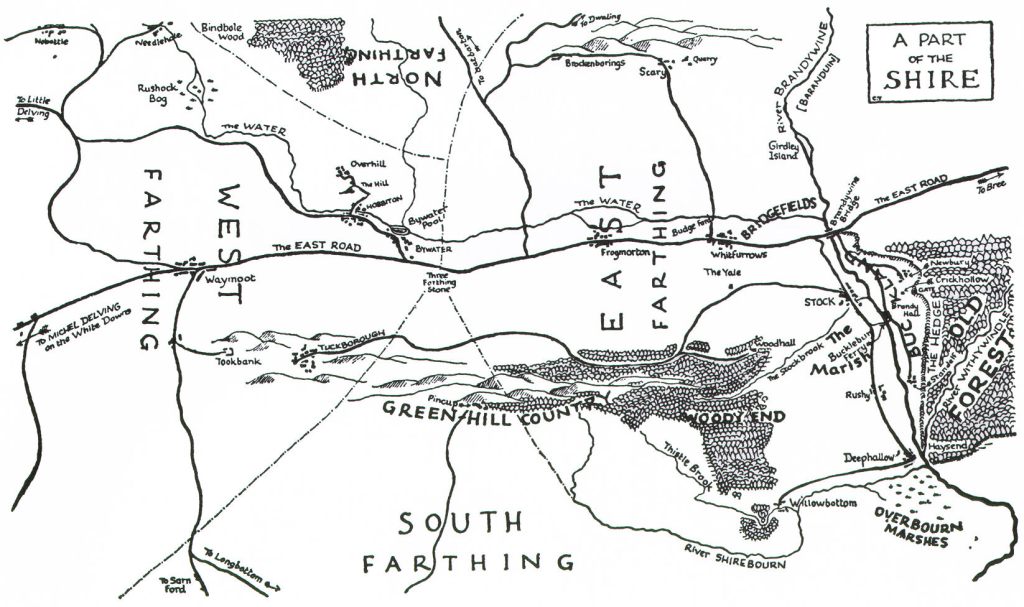

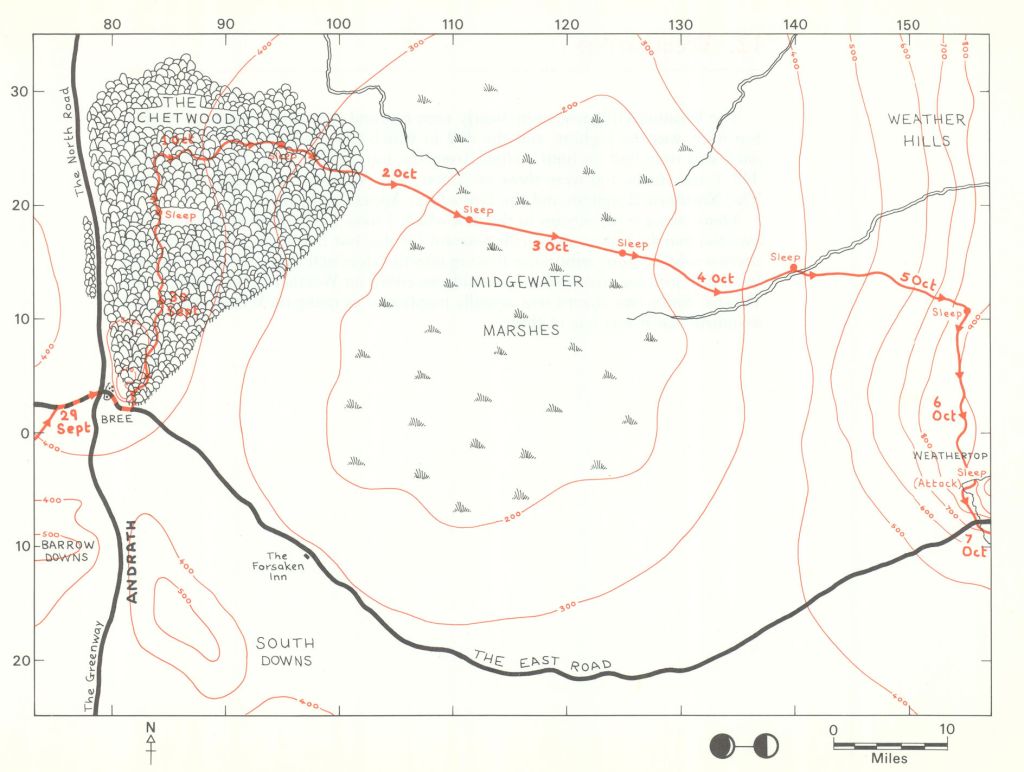

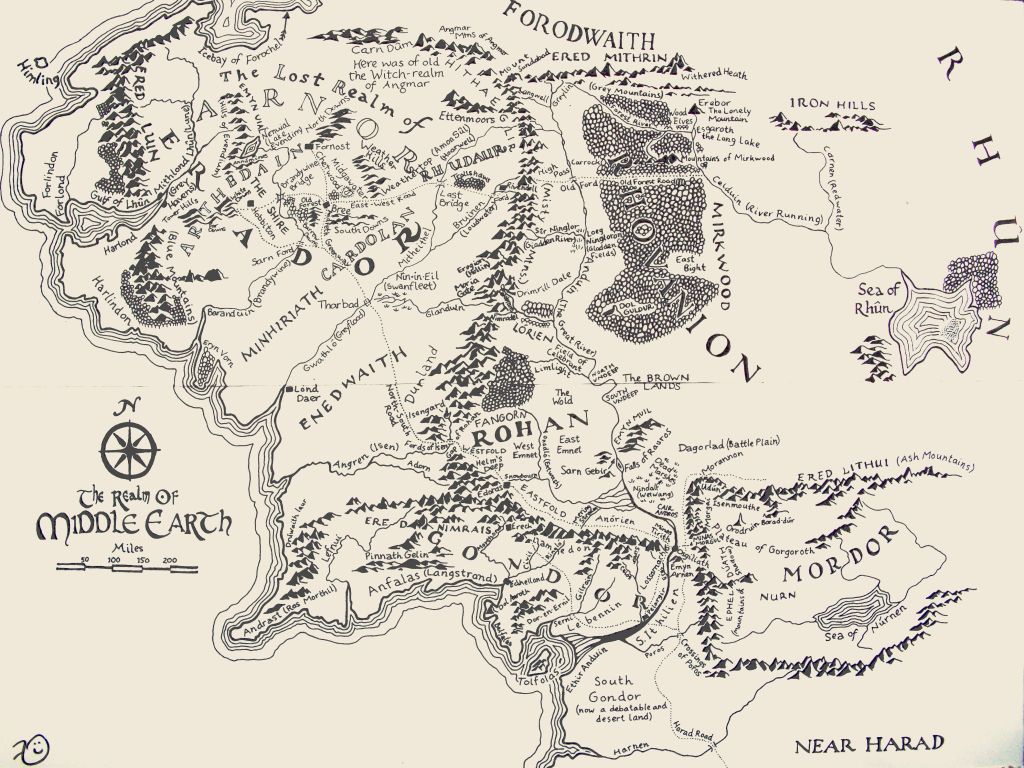

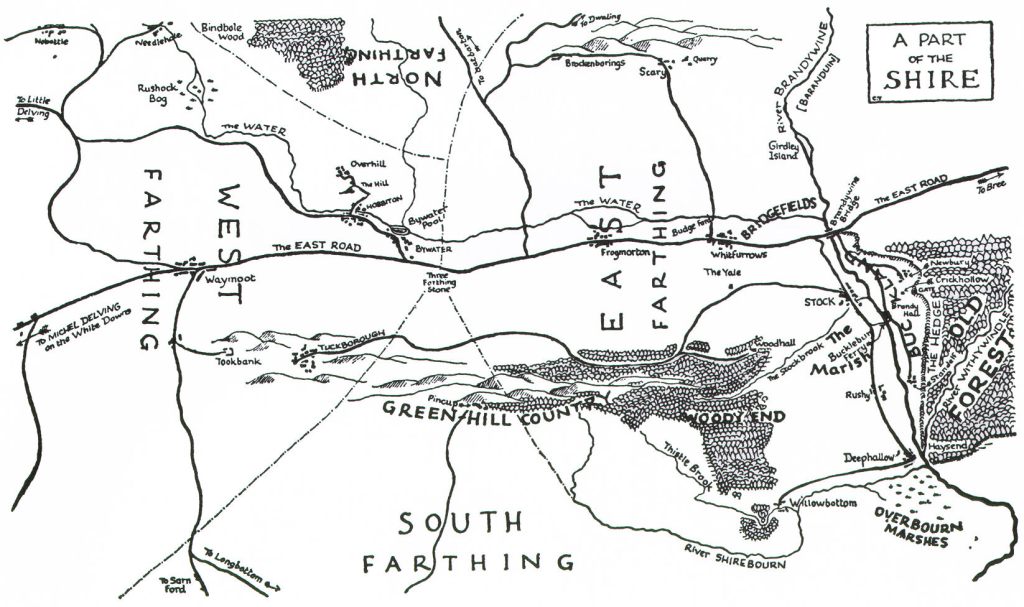

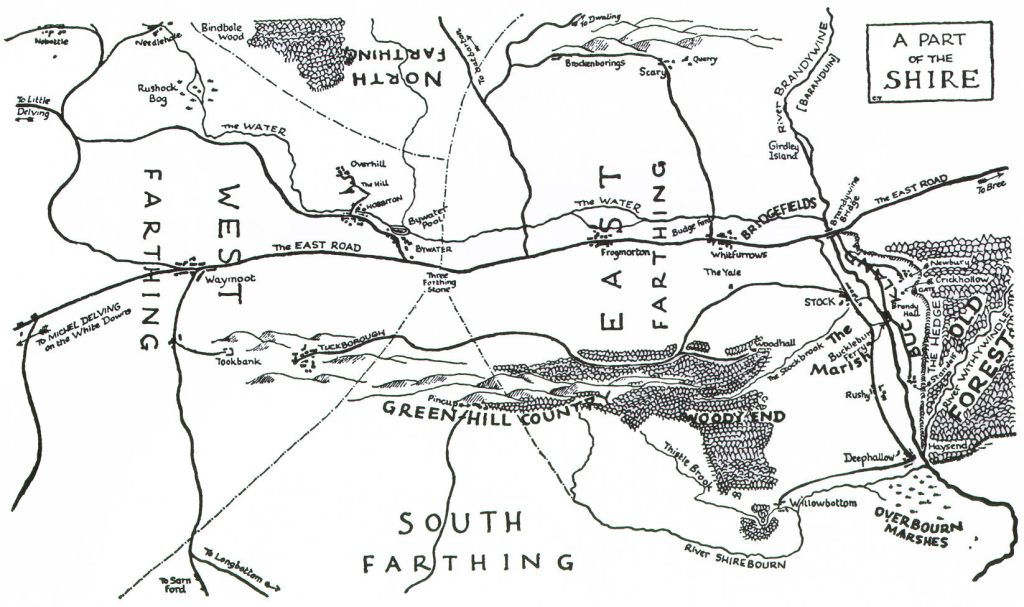

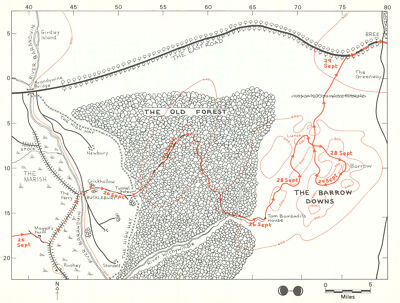

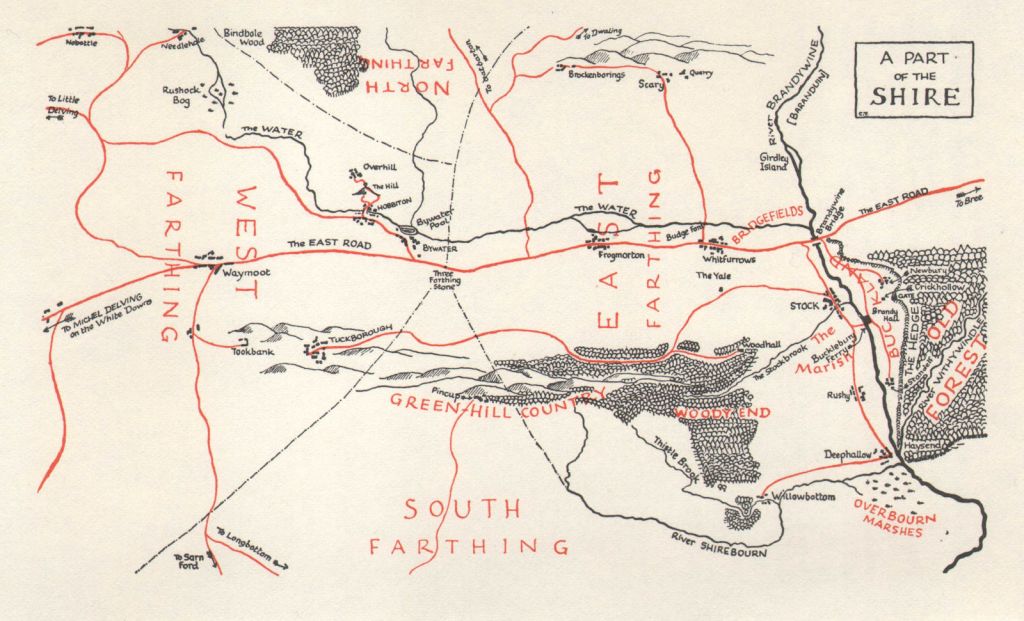

Thank goodness for a map—as, although I know the Isen from Isengard, I had no idea where the Lefnui was—and here, from the Tolkien Gateway, you can see both. And you can also wonder about how such forces got to Rohan, about which JRRT is completely silent, particularly those who landed at the mouth of the Lefnui, as, straight ahead of them would have been miles of the White Mountains. Long detour north, then east, through the Gap of Rohan, then southeast into Rohan itself?

(from the Encyclopedia of Arda)

To which they might add:

“In the days of Beren, the nineteenth Steward, an even greater peril came upon Gondor. Three great fleets, long prepared, came up from Umbar and the Harad, and assailed the coasts of Gondor in great force; and the enemy made many landings, even as far north as the mouth of the Isen. At the same time the Rohirrim were assailed from the west and the east, and their land was overrun, and they were driven into the dales of the White Mountains.” (Appendix A, (iv) Gondor and the Heirs of Anarion; The Stewards)

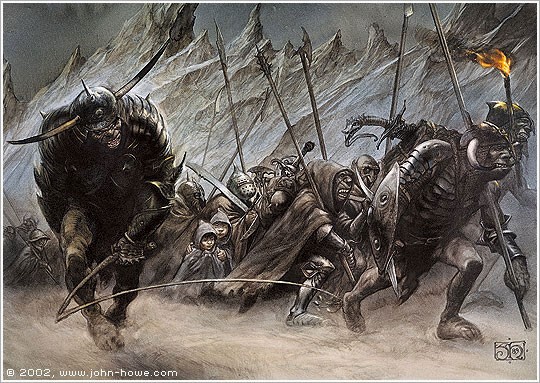

You can see where this argument might go: Wulf—the antagonist of The War of the Rohirrim—invades Rohan. His invasion force includes “…Enemies of Gondor that landed at the mouths of Lefnui and Isen” and those enemies, who were part of the fleet which attacked the west coast of Gondor, “…came up from Umbar and the Harad”, and we’re told in The Lord of the Rings that “…the Mumak of Harad was indeed a beast of vast bulk…” (The Two Towers, Book Four, Chapter 4, “Of Herbs and Stewed Rabbit”).

(Ted Nasmith)

So, their reasoning goes:

1. some of the Corsairs were from Harad

2. Harad is where Mumakil come from

3. some of the invasion force which followed Wulf were from the Corsairs who attacked the west coast of Gondor and therefore were from Harad

4. and thus there was the possibility that they might have brought Mumakil with them

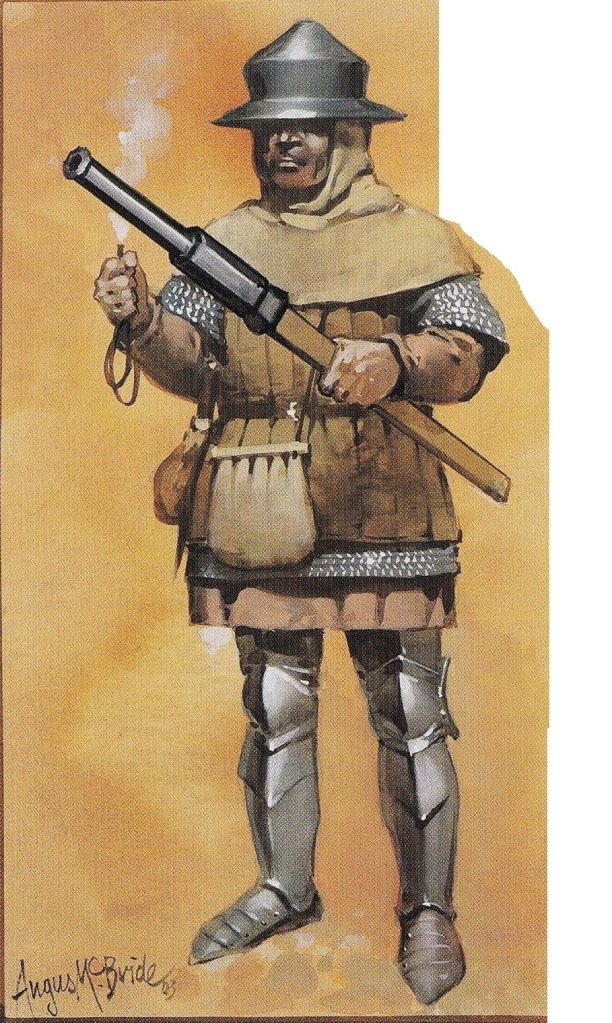

Back in 2024, I had written a posting (“Dos Mackaneeks”, 26 June, 2024—here: https://doubtfulsea.com/2024/06/26/dos-mackaneeks/ ) in which, while discussing “The Phantom Menace”, I had followed this reasoning: both Saruman and Sauron clearly have access to blasting material of some sort–Saruman’s forces blow a hole in the wall of Helm’s Deep and Sauron’s do the same with the Causeway Forts on their way into the Pelennor. And so, why would the next step not have been arming their orc armies with early “hand gonnes”?

(Angus McBride)

The answer is, they didn’t: because the author chose for them not to, even though he provided evidence that he could have. It’s clear that Tolkien was a very deliberate writer, taking years to construct his texts in draft after draft. And so, had he wanted to have Wulf’s forces include Mumakil, I would suggest that, as he chose to depict them both ambushed by Faramir’s rangers and forming part of the armies which attacked Minas Tirith, they were certainly a possibility at any other point in his long story, but they don’t appear there.

At base, the real problem here, as I and others have suggested, is the extreme thinness of the material upon which The War of the Rohirrim is based: it’s really only a little over two pages in Appendix A in my 50th Anniversary edition (1065-67). To flesh this out into a film more than 2 hours long, the script writers created a character named “Hera” out of the nearly-anonymous “Helm’s daughter”, making her a “shield maiden”, adding a nurse for her (“Olwyn”), and a kind of page (“Lief”), as well as constructing a childhood friendship for “Hera” and Wulf, among other additions to a very small story, which is really only background to the later story of Helm’s Deep.

If you read this blog regularly, you know that I dislike vicious reviews, mostly because, along with what they suggest about their authors, they’re usually simply not helpful, and I don’t write them. This is my second partial review of The War of the Rohirrim (see “Plain and Grassy”, 24 September, 2025, for the first part: https://doubtfulsea.com/2025/09/24/plain-and-grassy/ ) and, while I will continue to praise the enormous artistic effort which went into making this film—I’d love to see more anime of heroic stories—I wish someone would make an anime Beowulf, or Sir Gawaine and the Green Knight, just as easy examples—I also wish that the creators would move on—what about a Ramayana, for instance, if they wanted to choose a long-established story?—or, even better, create a completely new story, one in which there would be a fierce, independent heroine, rather than try to make her out of Arwen or Galadriel or invent one like “Tauriel” or “Hera”?

In the meantime, it’s back to Pooh and Piglet, as they try to trap the illusive Heffalump (which they never succeed in doing).

(E.H. Shepard)

As always, thanks for reading.

Stay well,

Enjoy the New Year and may it be a very happy one for you,

And remember that, as always, there’s

MTCIDC

O