Tags

Admiral Byng, badger, Candide, Chief of the Nazgul, Eowyn, Fantasy, Gandalf, Grima, grima-wormtongue, Helm's Deep, lotr, Pelennor Fields, pour-encourager-les-autres, Theoden, Tolkien, Voltaire

Welcome, as always, dear readers.

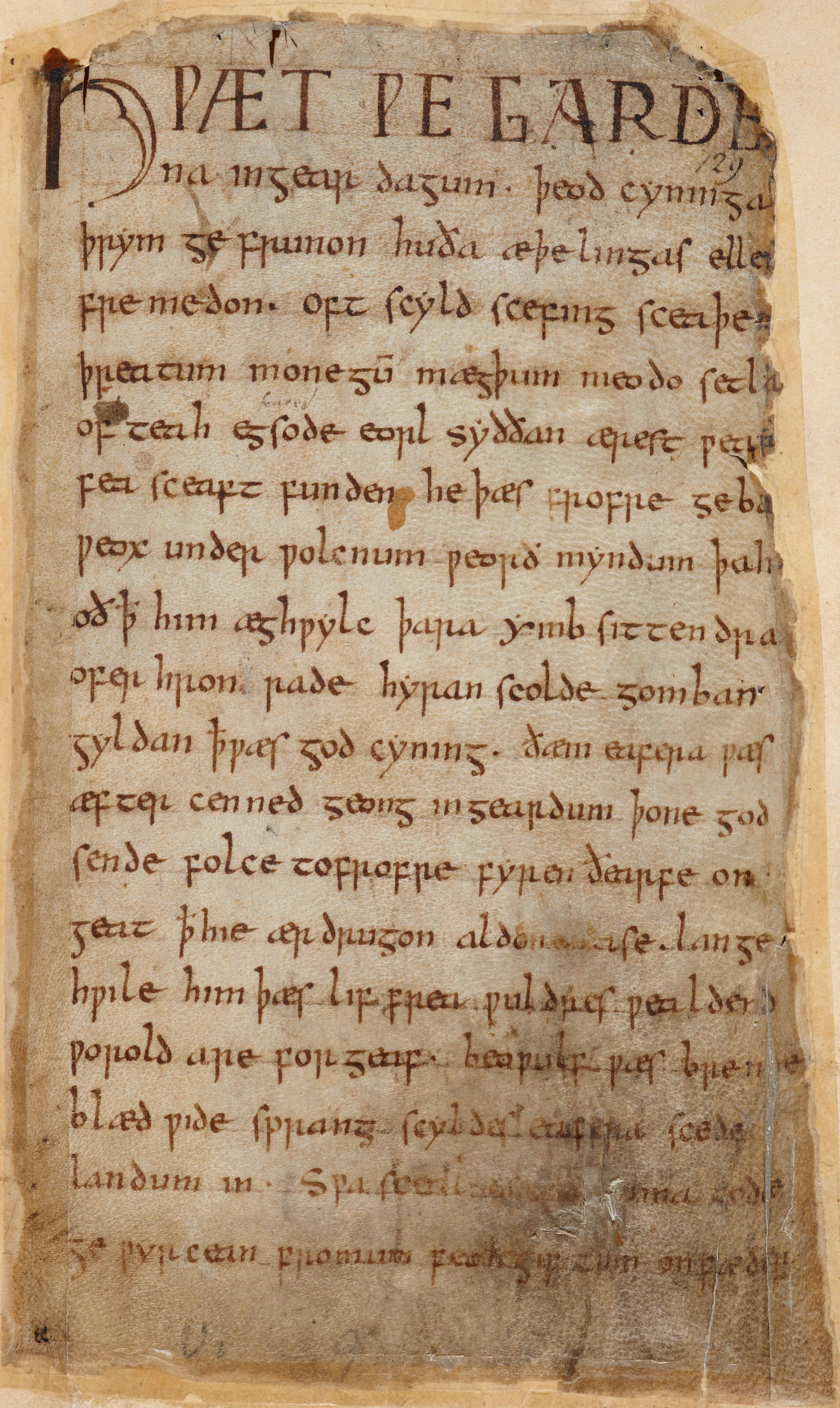

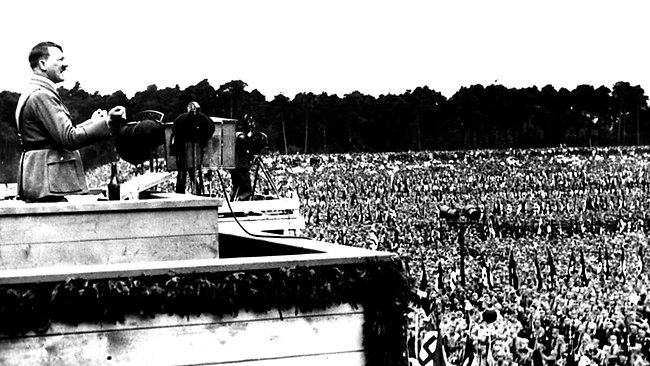

I almost feel like I should be delivering a parental warning before adding this terrible image.

This is the execution of a senior British naval officer, Admiral John Byng (1704-1757), by firing squad on the quarterdeck of HMS Monarch, 14 March, 1757, for what we might call “hesitation in the face of the enemy”. (For more on this, see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Byng#Death_warrant )

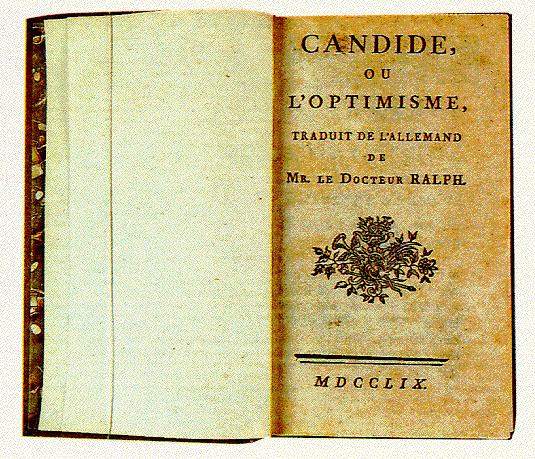

Byng was, it would seem, a scapegoat for poor naval policy and government mismanagement of the war with France, and this provoked the French philosopher, dramatist, and satirist, Voltaire (Francois-Marie Arouet, 1694-1778),

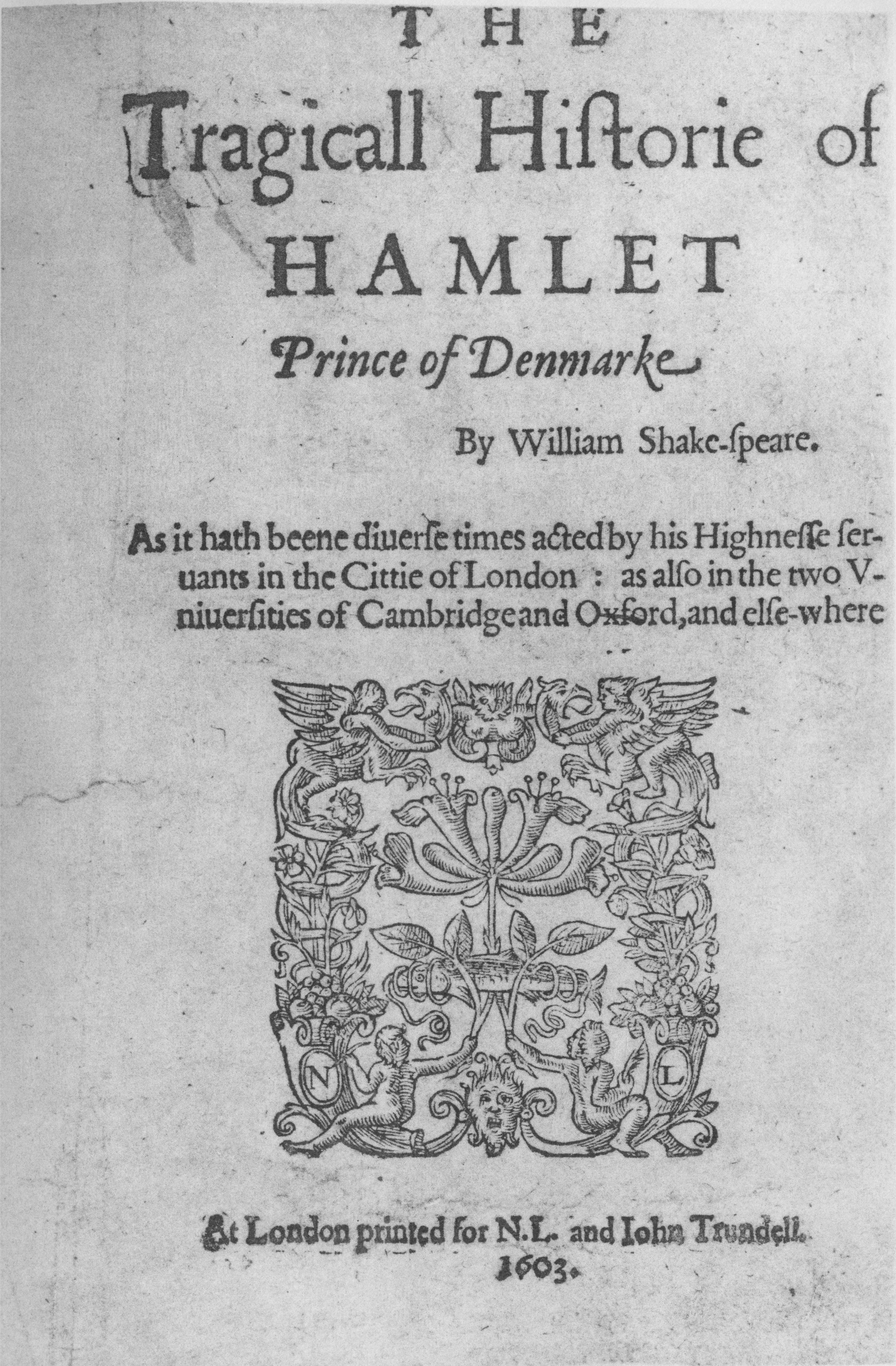

who had a personal connection to Byng, to include his death in his satirical novel, Candide (1759).

(Because of its controversial nature, the novel was published outside France and, as you can see by this image of the title page of the first edition, not even under the author’s name—for more on this see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Candide )

In Chapter XXIII, entitled “Candide and Martin Land on the English Coast: What They See There”, we read a description of Byng’s execution—although Byng himself is never named, the victim simply being called “un Amiral”—“an admiral”. Puzzled as to what’s happening, Candide asks who the man is and why he’s being shot, the reply becoming a classic quotation: “Mais dans ce pays-ci il est bon de tuer de tems en tems un Amiral pour encourager les autres.”—“But in this country it’s good to kill an admiral, from time to time, in order to put heart in the others.”

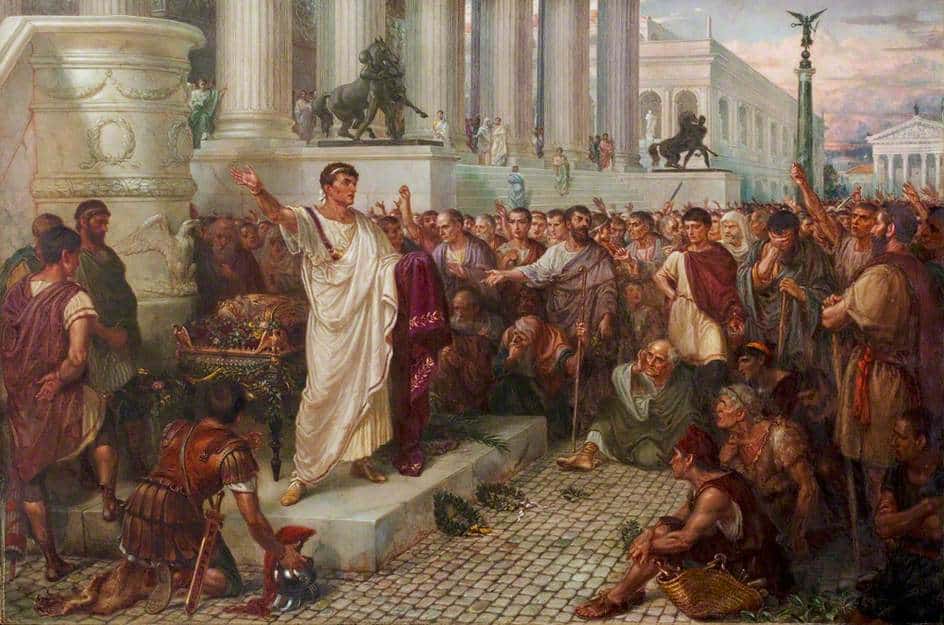

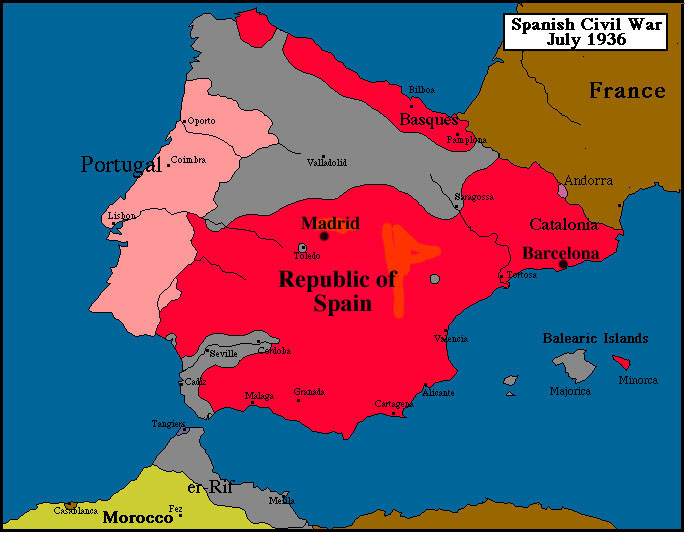

This is obviously meant as a jab at what Voltaire thought of as the barbaric behavior of Britain towards a distinguished officer, but it made me think about that “putting heart” in a military context in The Lord of the Rings. Here, however, instead of focusing upon encouraging the leaders, as Voltaire has mockingly remarked, I want to examine how certain leaders try—or don’t try—to do the same for their followers, focusing upon two kings, Theoden

(Michael Kaluta—you can see more of his work here: https://www.kaluta.com/ )

and the chief of the Nazgul.

(Erin Kelso—you can see more of her work here: https://www.cuded.com/illustrations-by-erin-kelso/ )

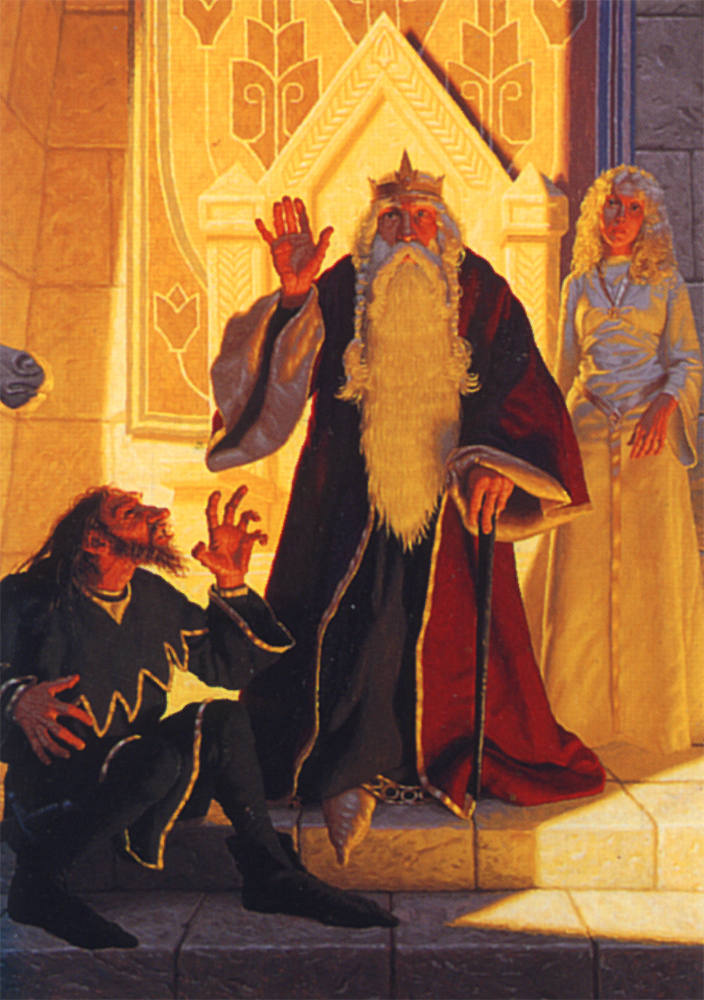

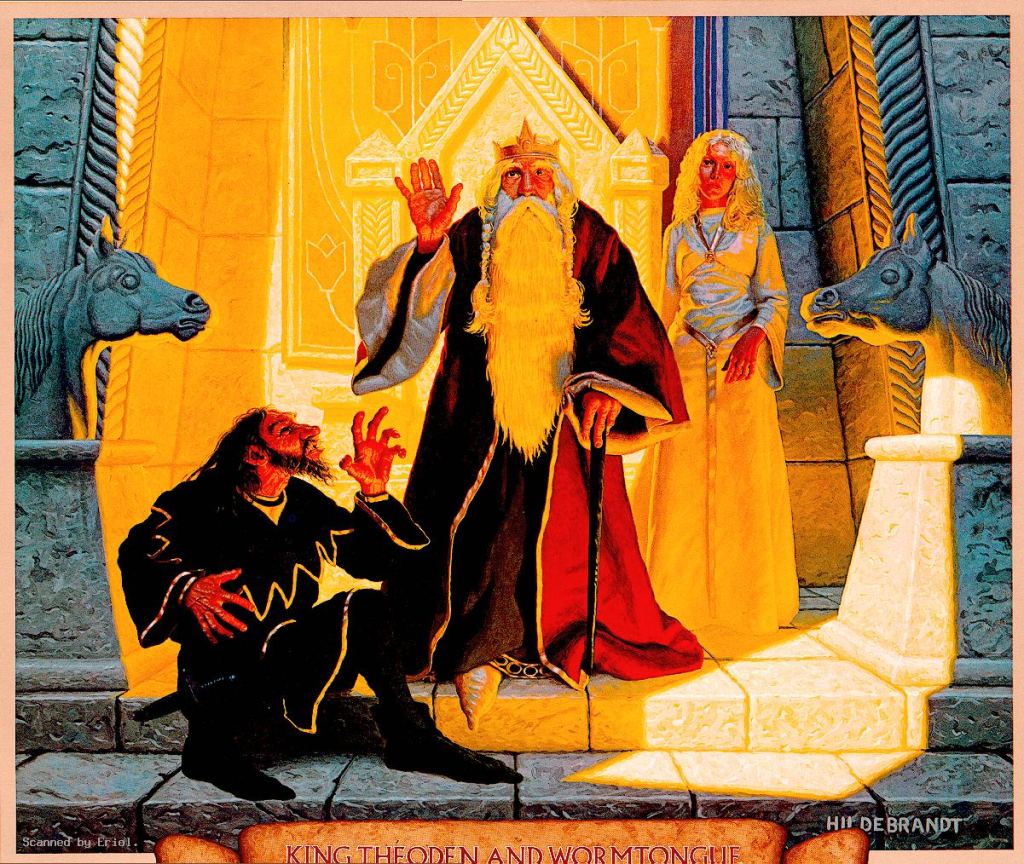

Theoden, when we first meet him, has almost lapsed into senescence and certainly has developed a hostility towards those who were once his allies.

(the Hildebrandts)

“Slowly the old man rose to his feet, leaning heavily upon a short black staff with a handle of white bone…

‘I greet you…and maybe you look for welcome. But truth to tell your welcome is doubtful here, Master Gandalf. You have ever been a herald of woe. Troubles follow you like crows, and ever the oftener the worse. I will not deceive you: when I heard that Shadowfax had come back riderless, I rejoiced at the return of the horse, but still more at the lack of the rider…”

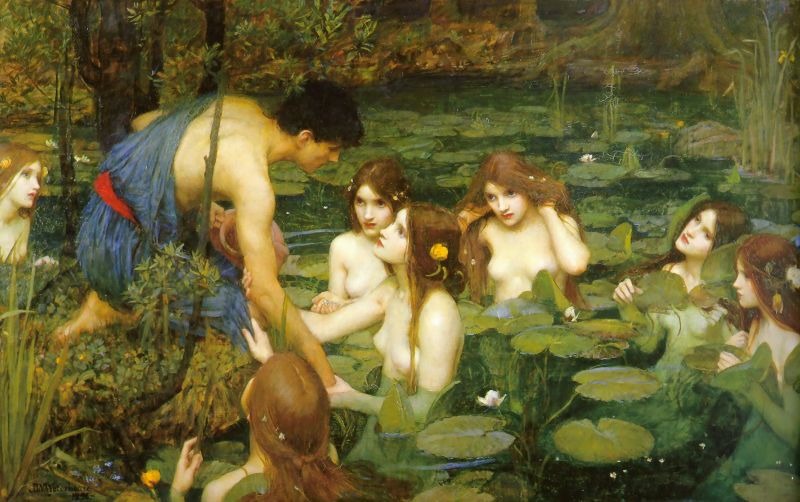

It soon turns out that this hostility—and, perhaps the senescence—are the work of Theoden’s counselor, Grima Wormtongue.

(Alan Lee)

“Wormtongue” would seem a strange epithet for a counselor, unless we remember Bilbo’s experience with Smaug, where, because of Smaug’s speech, Bilbo begins to question his trust in the dwarves: “That is the effect that dragon-talk has on the inexperienced.” (The Hobbit, Chapter 12, “Inside Information”) “Wormtongue”, then, can suggest persuasiveness—but maybe persuasiveness to be wary of, which is certainly the case here, where it’s clear that Grima is, in fact, behind Theoden’s look and behavior, and, freed from Grima by Gandalf, Theoden becomes a different man, taking Eomer’s sword and

“As his fingers took the hilt, it seemed to the watchers that firmness and strength returned to his thin arm. Suddenly he lifted the blade and swung it shimmering and whistling in the air. Then he gave a great cry. His voice rang clear as he chanted in the tongue of Rohan a call to arms.

‘Arise now, arise, Riders of Theoden!

Dire deeds awake, dark is it eastward.

Let horse be bridled, horn be sounded!

Forth Eorlingas!’ “

And here’s where the encouragement begins:

“The guards, thinking that they were summoned, sprang up the stair. They looked at their lord in amazement, and then as one man they drew their swords and laid them at his feet. ‘Command us!’ they said.

‘Westu Theoden hal!’ cried Eomer. ‘It is a joy to us to see you return into your own. Never again shall it be said, Gandalf, that you come only with grief!’ “ (The Two Towers, Book Three, Chapter 6, “The King of the Golden Hall”)

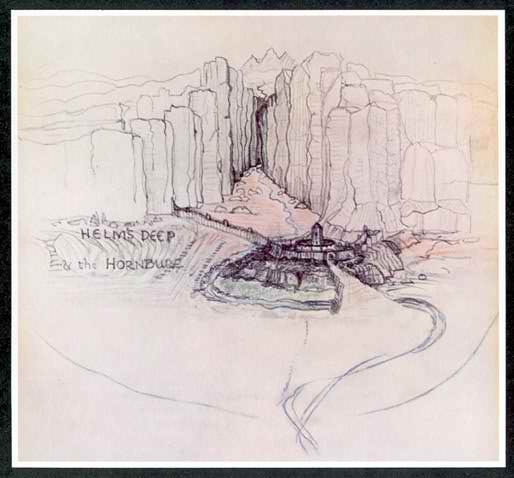

The King’s sudden energy energizes his men, and that energy is mixed with a kind of fierce joy, which Theoden will soon need as it is learned that Saruman is directing an attack against Rohan. With the threat of being overwhelmed, Theoden and the others enter the stronghold of Helm’s Deep.

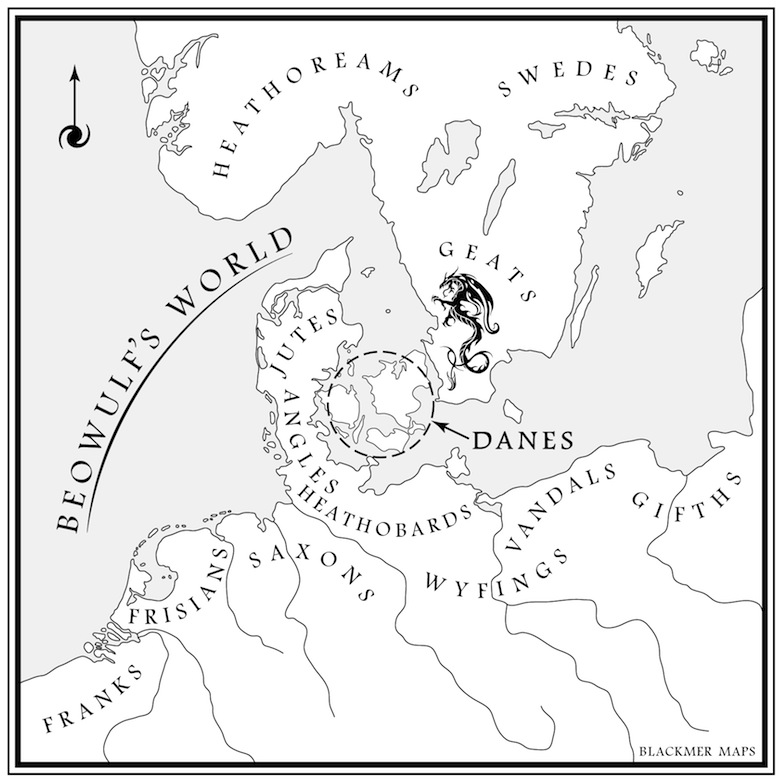

(JRRT)

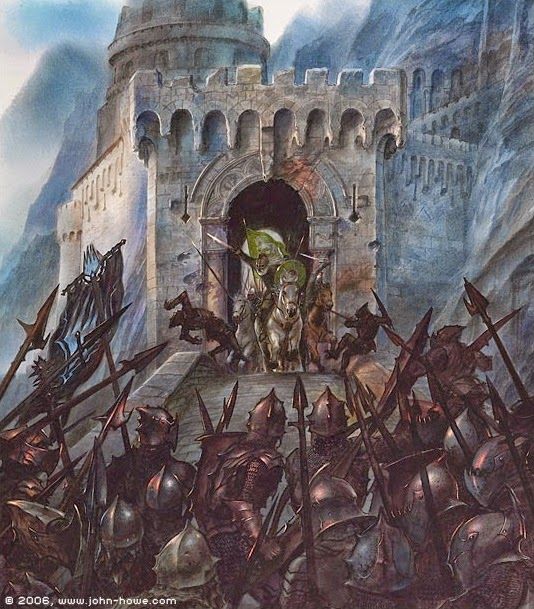

There, with the threat of Saruman’s “blasting fire”, Theoden decides to make a sortie—that is, to make a mounted attack on the besieging forces outside the walls and here we see his determination—even if it’s of a grim variety:

“ ‘But I will not end here, taken like an old badger in a trap…When dawn comes, I will bid men sound Helm’s horn, and I will ride forth. Will you ride with me then, son of Arathorn? Maybe we shall cleave a road, or make such an end as will be worth a song—if any be left to sing of us hereafter.’ “

(In fact, badgers, when cornered, are very fierce, as I’m sure that JRRT was aware, seizing an opponent in a kind of death grip. For more, see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Badger#Culling )

He then leads a charge of the traditional “hell for leather” sort, which JRRT would have known from such earlier historical events as the charge of the Light Brigade at Balaclava in October, 1854—

and, once again, we see a kind of fierce excitement which the King brings to his men.

“ ‘Helm! Helm!’ the Riders shouted. ‘Helm is arisen and comes back to war. Helm for Theoden King!’

And with that shout the king came. His horse was white as snow, golden was his shield, and his spear was long….Light sprang in the sky. Night departed.

‘Forth Eorlingas!’ With a cry and a great noise they charged. Down from the gates they roared, over the causeway they swept, and they drove through the hosts of Isengard as a wind among grass.” (The Two Towers, Book Three, Chapter 7, “Helm’s Deep”)

(John Howe)

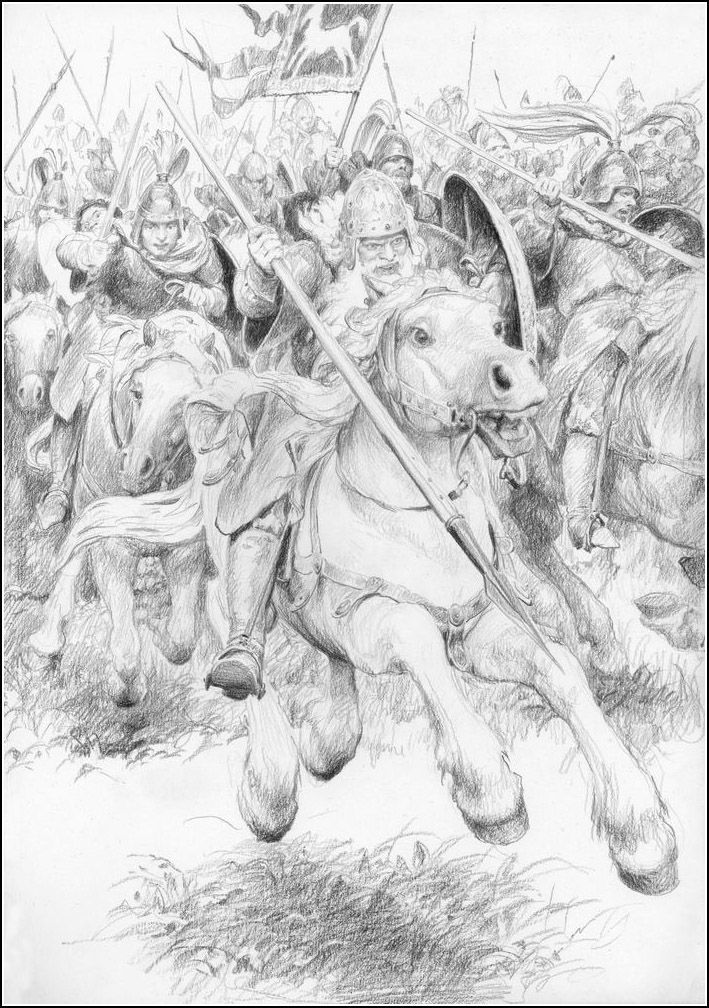

Theoden will repeat this at his final battle in the Pelennor Fields–

(Denis Gordeev)

“At that sound the bent shape of the king sprang suddenly erect. Tall and proud he seemed again and rising in his stirrups he cried in a loud voice, more clear than any there had ever heard a mortal man achieve before:

‘Arise, arise, Riders of Theoden!

Fell deeds awake: fire and slaughter!

spear shall be shaken, shield be splintered,

a sword-day, a red day, ere the sun rises!

Ride now, ride now! Ride to Gondor!’

Suddenly the king cried to Snowmane and the horse sprang away. Behind him his banner blew in the wind, white horse upon a field of green, but he outpaced it. After him thundered the knights of his house, but he was ever before them…And then all the host of Rohan burst into song, and they sang as they slew, for the joy of battle was on them, and the sound of their singing that was fair and terrible came even to the City.” (The Return of the King, Book Five, Chapter 5, “The Ride of the Rohirrim”)

We can see now how Theoden’s encouragement works: he’s always in the lead and he has stirring words in poetic form to give heart to his followers.

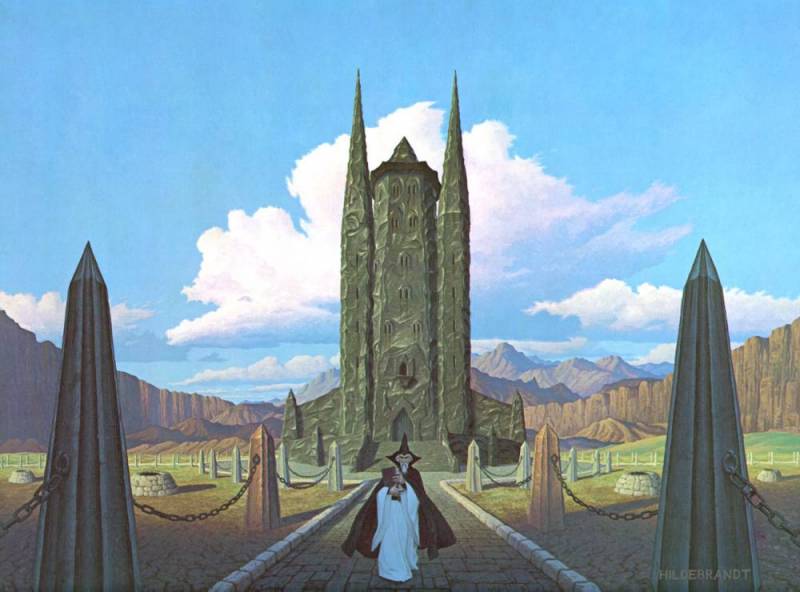

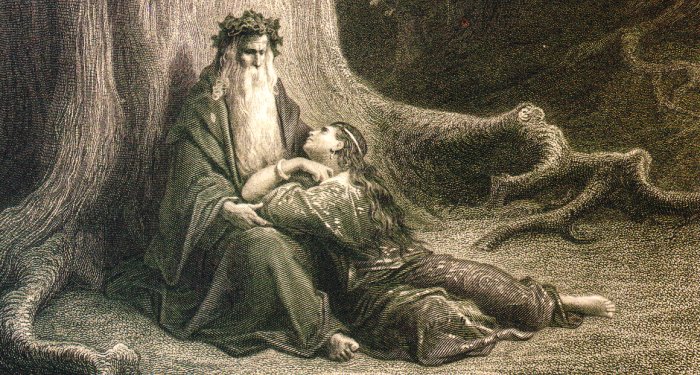

In contrast, there is the chief of the Nazgul, once a king himself.

(Darrell K. Sweet—you can see more of his work here: https://blackgate.com/2022/04/17/an-adventure-to-be-had-a-journey-through-the-art-of-darrell-k-sweet/ )

Unlike Theoden, who has had a kind of rebirth, that chief is clearly one of the undead, a disturbing figure among a group of disturbing figures, as we hear in Grishnakh’s reaction—

“ ‘Nazgul, Nazgul,’ said Grishnakh, shivering and licking his lips, as if the word had a foul taste that he savoured painfully. ‘You speak of what is deep beyond the reach of your muddy dreams, Ugluk!’ “ (The Two Towers, Book Three, Chapter 3, “The Uruk-hai”)

His method of leading is also disturbing—as an anonymous messenger says of him:

“ ‘But it is the Black Captain that defeats us. Few will stand and abide even the rumour of his coming. His own folk quail at him, and they would slay themselves at his bidding.’ “ (The Return of the King, Book Five, Chapter 4, “The Siege of Gondor”)

To which we can add Gandalf’s description:

“…the Captain of Despair does not press forward yet. He rules rather according to the wisdom that you have just spoken, from the rear, driving his slaves in madness on before.’ “

Unlike Theoden, he has no poetry and virtually no words—certainly nothing encouraging. His only two speeches are full of contempt, addressed to Gandalf, at the ruined gate of Minas Tirith–The Return of the King, Book Five, Chapter 4, “The Siege of Gondor”—and to Eowyn—The Return of the King, Book Five, Chapter 6, “The Battle of the Pelennor Fields”, although before he sneers at Gandalf, he seems to chant a spell of some sort to help Grond destroy the gate—

“Then the Black Captain rose in his stirrups and cried aloud in a dreadful voice, speaking in some forgotten tongue words of power and terror to rend both heart and stone.

Thrice he cried. Thrice the great ram boomed. And suddenly upon the last stroke the Gate of Gondor broke. As if stricken by some blasting spell it burst asunder: there was a flash of searing lightning, and the doors tumbled in riven fragments to the ground.” (The Return of the King, Book Five, Chapter 4, “The Siege of Gondor”)

It seems then, that, in contrast to Theoden, the chief of the Nazgul’s only method of encouragement is the very opposite of giving heart, being more like what Voltaire suggested was behind the execution of poor Admiral Byng: the desire to create fear. Does it work? Britain defeated France at sea, their greatest victory being at Quiberon Bay in 1759,

although Hawke, the British admiral there, had always been an aggressive and imaginative sailor (who had also testified against Byng) and would have needed no threat of court martial to spur him on.

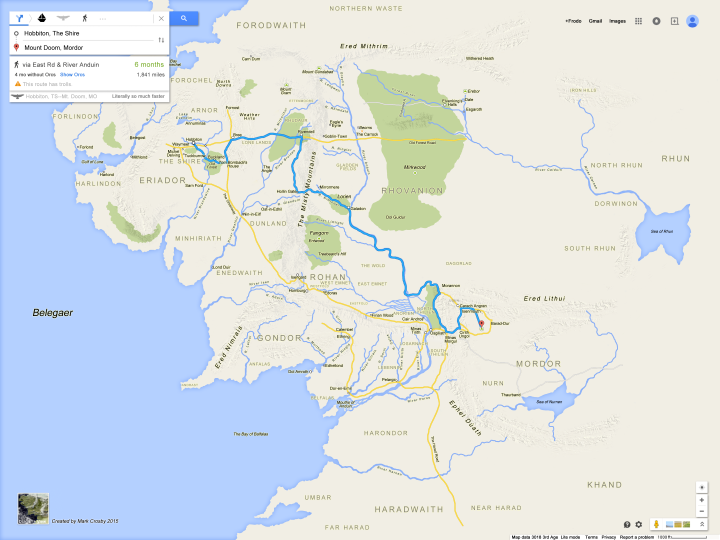

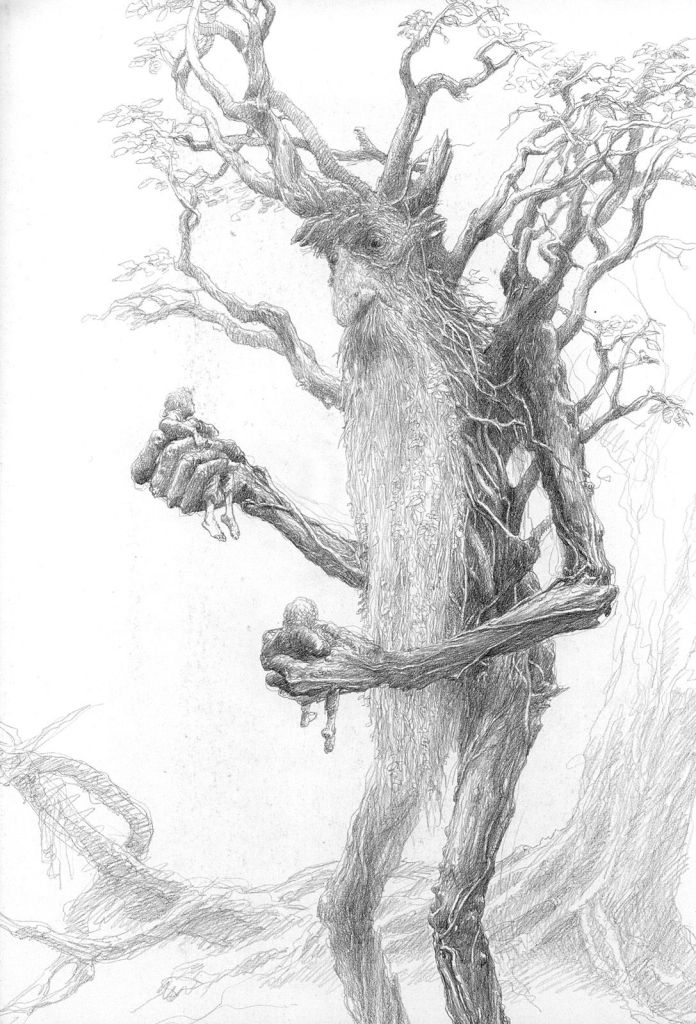

With the aid of Fangorn,

(Alan Lee)

the Ents, and Gandalf, Theoden’s men destroy Saruman’s army at Helm’s Deep, and, with the aid of Aragorn, his men ruin Sauron’s plans for Gondor, which leads, with the destruction of the Ring, to the destruction of Sauron himself.

(Ted Nasmith)

The end of Sauron brought peace and a new Age to Middle-earth. War broke out again between Britain and France in 1778, which led to the loss of 13 of Britain’s North American colonies, and there was war with France again between 1793 and 1815. Granted that the wars of our Middle-earth are often larger and more long-lasting (no Ring to destroy Napoleon—although Britain, I’m sure, would have been glad of one) but, given the choice, I, for one, would rather follow Theoden than a Nazgul.

Thanks, as always, for reading.

Stay well,

When you think of Theoden, imagine this wonderful creation made from Legos,

And remember that, as ever, there’s

MTCIDC

O

PS

For an English translation of Chapter 18 of Candide:

https://www.gutenberg.org/files/19942/19942-h/19942-h.htm#Page_122

For more about Voltaire and Admiral Byng: https://voltairefoundation.wordpress.com/2020/05/20/pour-encourager-les-autres-admiral-byng-voltaire-and-the-1756-battle-of-minorca/