Tags

A New Hope, A Princess of Mars, Ages of Middle-earth, Death Star, Edgar Rice Burroughs, Emperor Palpatine, Frank Schoonover, George Lucas, Hildebrandt, Mos Eisley, Oxford, Percival Lowell, Return of the Jedi, Sauron, science fiction, special effects, Star Wars, Stonehenge, Tatooine, The Empire Strikes Back, The History of Middle-earth, The Last Jedi, The Lord of the Rings, Tolkien, tower of St Michael

Welcome, as always, dear readers.

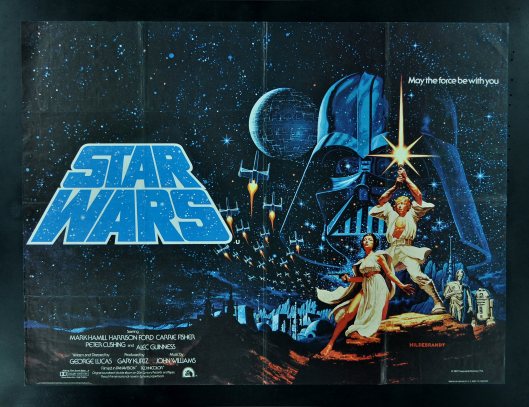

As The Last Jedi (Star Wars 8) approaches (and Star Wars Rebels, season 3 has appeared via the postman—season 4 premieres in mid-October—sadly the last season, as Disney has canceled season 5), we’ve been thinking about the original Star Wars of 1977.

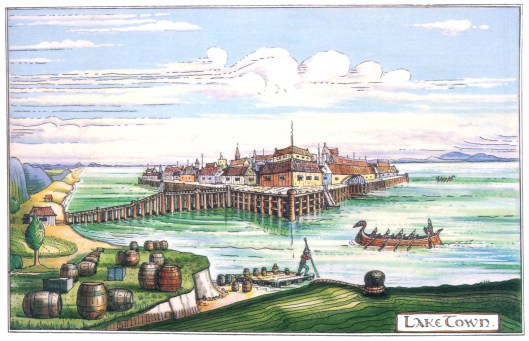

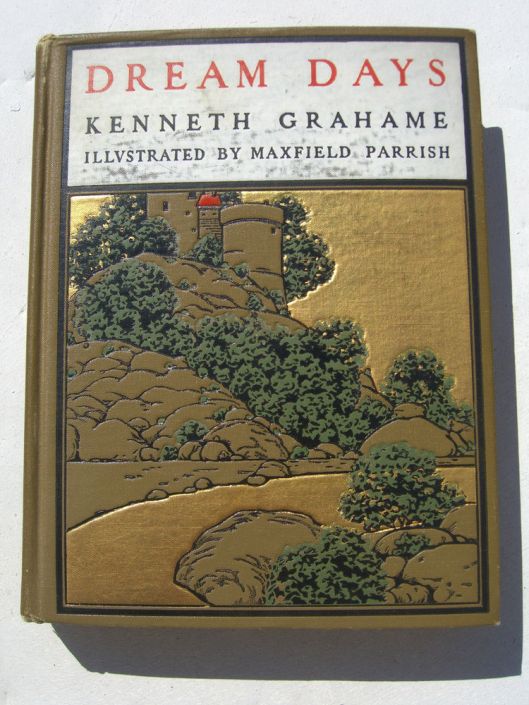

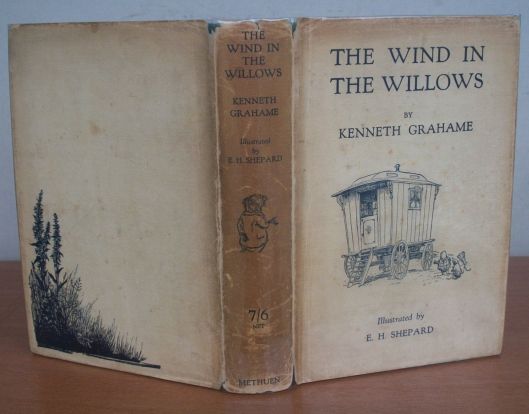

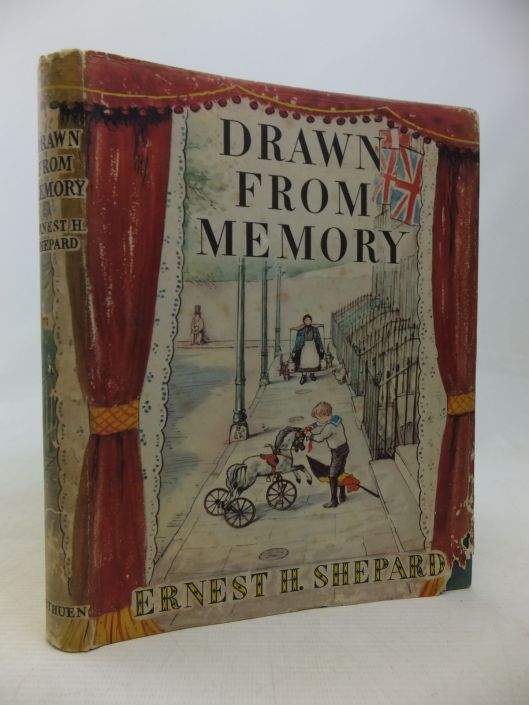

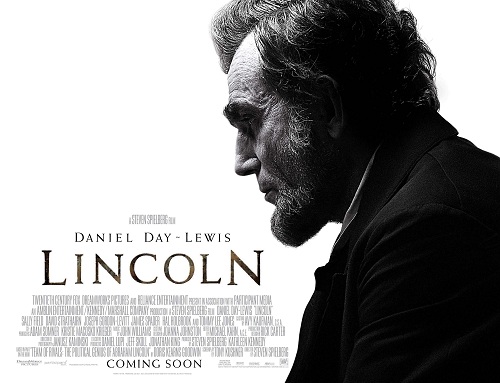

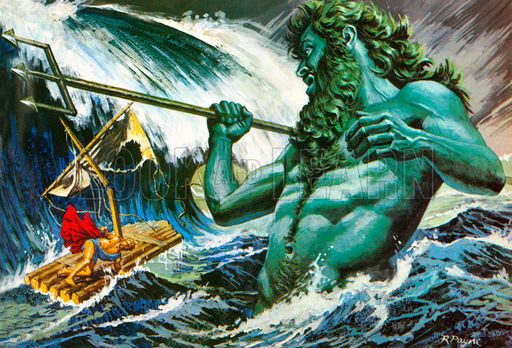

This poster—the second ever Star Wars poster, in fact (used by 20th Century Fox in the UK)– is a great link to JRRT—as if we don’t seem to make such links every time we write! It’s by two of our favorite Tolkien illustrators, the Hildebrandt brothers. Here’s a picture of the surviving twin, Greg, with that very poster (his brother, Tim, died in 2006).

(Clink here for a LINK to an interesting little piece from 2010 about the Hildebrandts and George Lucas.)

We believe, however that there may be a deeper link.

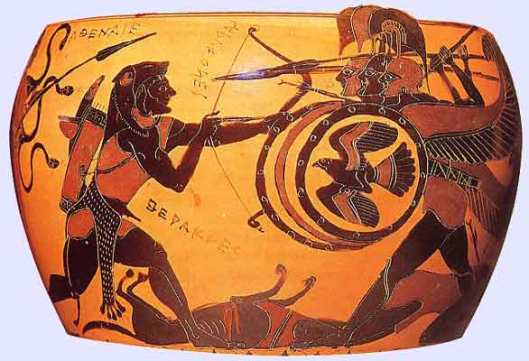

The original reviews (here’s a LINK to summaries of some of them) were a mixture, with some critics enthusiastic about what they saw and others (in our view the stodgier ones) calling the film things like “puerile”. One element which was occasionally commented upon was the look of the picture—and not just the (for the time) dazzling special effects—but the fact that all the worlds depicted were lived-in, not shiny and new—well, almost. Consider Mos Eisley, for example,

which looks dusty and battered, suggesting the passage of time as well as the effects of the harsh desert climate of Tatooine.

Or the Jawa sandcrawler, old and clearly rusting–

We said “almost” shiny and new because there’s one part of this galaxy with a different look: the Death Star.

It looks like it’s dusted and waxed hourly, doesn’t it? And the outside appears to be just as neat.

What does this say about the nature of those who inhabit it? For us, thinking about the spotless Darth Vader,

immediately suggests that the old proverb should be changed to “Cleanliness is next to Un-godliness”! (Okay—we’re not the neatest and most organized people we know.)

It has been pointed out, more than once and beginning with the director himself, that George Lucas was influenced by Edgar Rice Burroughs’ John Carter series, beginning with A Princess of Mars (first published serially in The All-Story, February to July, 1912).

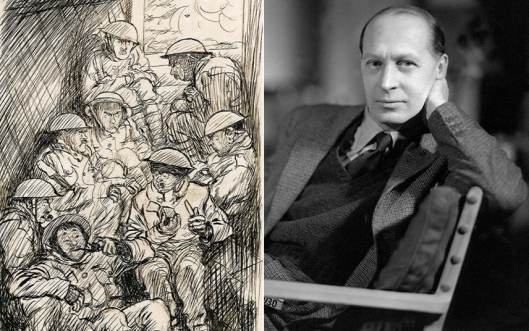

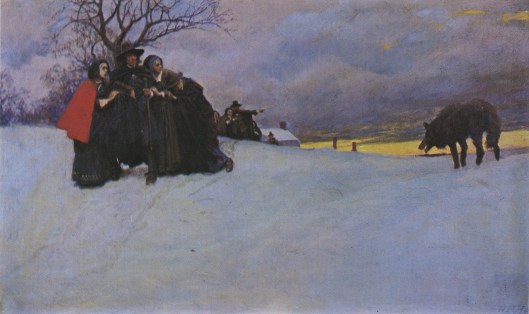

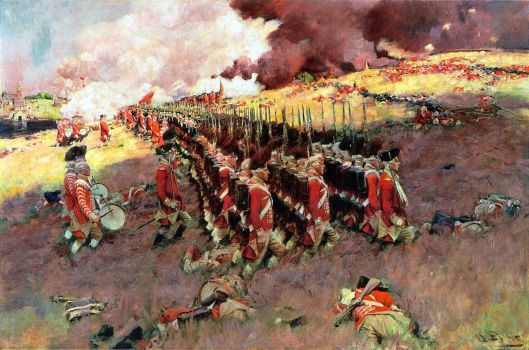

(And here’s another connection—this cover and the illustrations for its first publication in book form, in 1917, were by Frank Schoonover, 1877-1972, who was the student of another of our favorite illustrators, Howard Pyle, whom we have occasionally mentioned in previous postings. The convincing detail in this cover painting shows that, just like his teacher, Schoonover did his research—in his case, by very carefully going through the text and taking note of any technical information the author might have mentioned.)

In A Princess of Mars and subsequent books, Mars has a civilization which is old and in decline (the inspiration for which, in turn, may have come from the work of the amateur astronomer, Percival Lowell, 1855-1916, whose telescopic observations of Mars had convinced him that the planet was—or had been—the home of a dying civilization which had constructed a vast network of canals to supply themselves with water from the polar ice caps—unfortunately, numerous NASA missions have found no evidence of the desperate Martians or their canals). It would be easy, then, to say that Lucas was just following his source material, but we would suggest that there are two better explanations for showing wear.

The first comes from something Lucas is quoted as having said to his production designers: “What is required for true credibility is a used future.” In Lucas’ view, then, the story’s believability comes in part from its look: if things appeared not shiny, but worn, then viewers would be more likely to accept the narrative as somehow “true”, we presume because things in our world so often look used.

There is then, we think a further presumption: if things look worn, then they have a past, which implies that the here-and-now of the story is a small part of bigger things and, certainly, just looking at the “crawl” at the beginning of the original Star Wars,

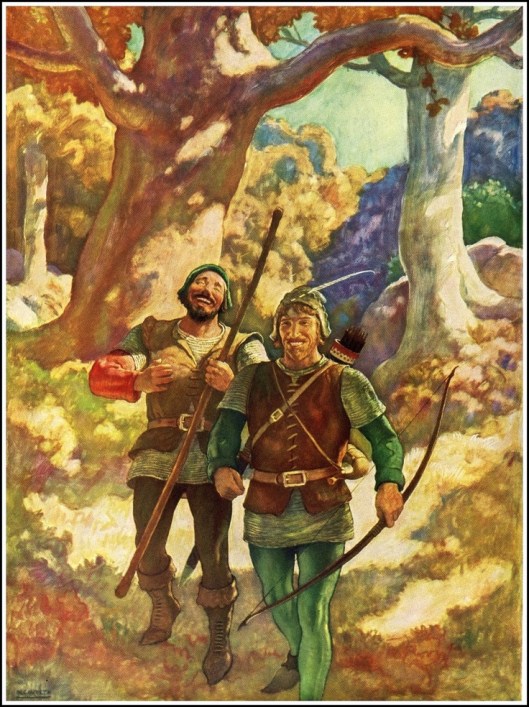

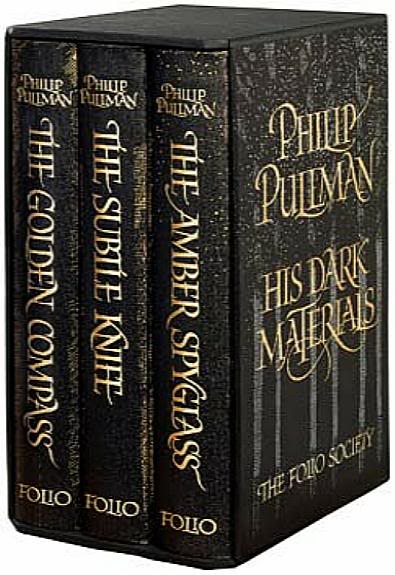

which leads us to our second explanation. This one deals with something deeper, something which we would say might provide another possible link with JRRT and is, in fact, suggested by the titles of the first three Star Wars films made and even in their sequence: A New Hope, The Empire Strikes Back, The Return of the Jedi.

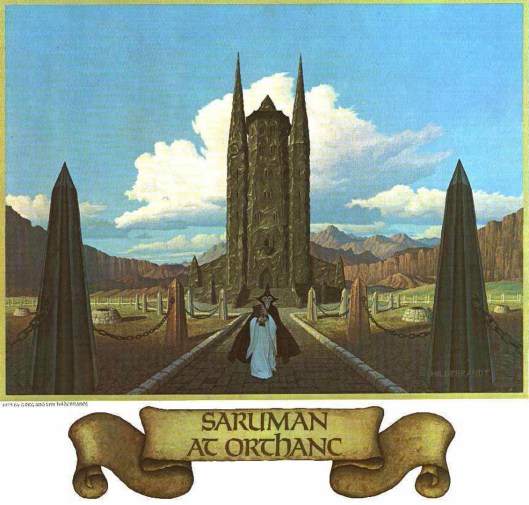

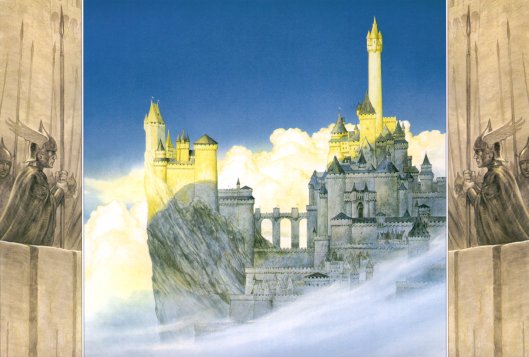

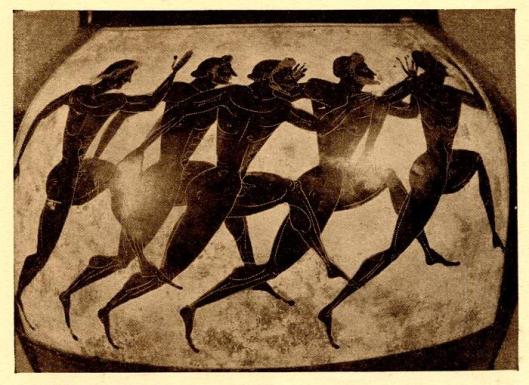

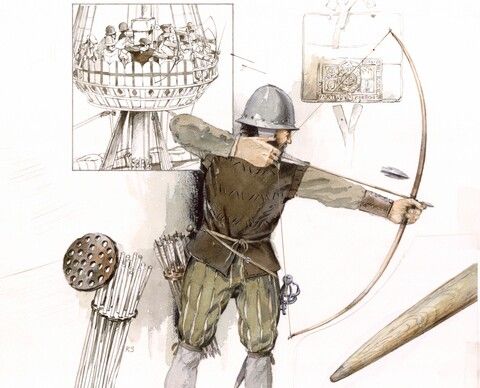

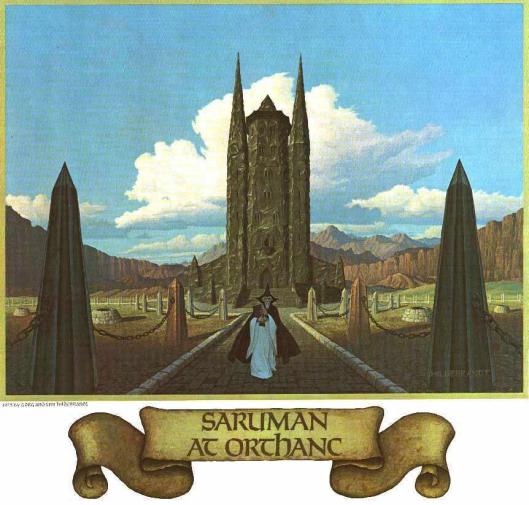

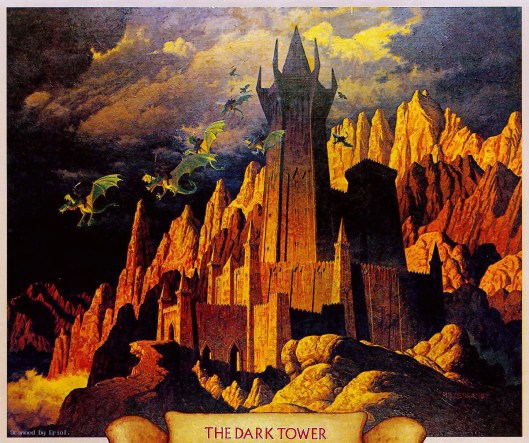

In two earlier postings, we talked about the condition of Middle-earth at the beginning of The Lord of the Rings, in which everything, from the trees to the houses of Minas Tirith, has grown old and weary—and even potentially hostile, in the case of the trees. Part of this comes from the fact that Middle-earth is old: one has only to turn to Appendix B, subtitled “The Tale of Years”, in The Lord of the Rings to see that, in the Second and Third Ages alone, nearly 6000 years have passed. (In terms of our earth, that’s moving from the late Neolithic Era to modern times, 4000bc to 2017ad.) This also emphasizes the age and depth of evil, as well as its power to corrupt in the present: Sauron began to build Barad-dur c. SA1000—5000 years before the main narrative of The Lord of the Rings opens and, in the present, the world is crumbling.

Of course, JRRT lived surrounded by the past. The oldest surviving building in his daily Oxford is the tower of St Michael at the North Gate, dating from 1040ad, nearly a thousand years before his time,

but Neolithic Stonehenge is only 58 miles (93km) southwest of the city and that’s 5000 years old, taking us back to the time when, in Middle-earth, Sauron had begun the Barad-dur.

In contrast, Lucas was born in 1944 in Modesto, California, a town only founded in 1870, and grew up in a post-World War II world, where the key was “the future”. It is a tribute, then, to his story-telling gift that he realized how useful in telling his story the past—even an imagined one—could be and it is interesting to see how he shares that understanding with JRRT and perhaps shares a goal, as well.

We’ve said that our second explanation may be seen in the titles of Lucas’ three films, so let’s consider them in comparison with the general shape of Tolkien’s work to see what that shared goal might be. (In an interview, Lucas even described the three as being like a three-act play, suggesting the dramatic progress inherent in the movement from one to another.)

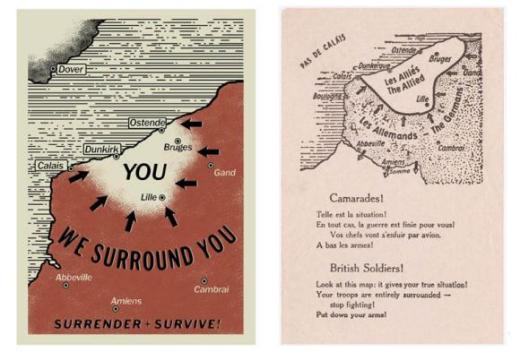

At the beginning of the first film, it is a dark time in the galaxy: the repressive regime of the evil Emperor Palpatine dominates and resistance is confined to “The Rebel Alliance”, which has scraped together a fleet (and, presumably an army—we see elements in Rogue One, which takes place before this film) to resist, but seems to spend most of its time running and hiding. The past is only implied, but the fact that there is an Empire and a resistance suggests much, just as the run-down condition of places like Tatooine might suggest both age and that the galaxy has become run-down because of that Empire.

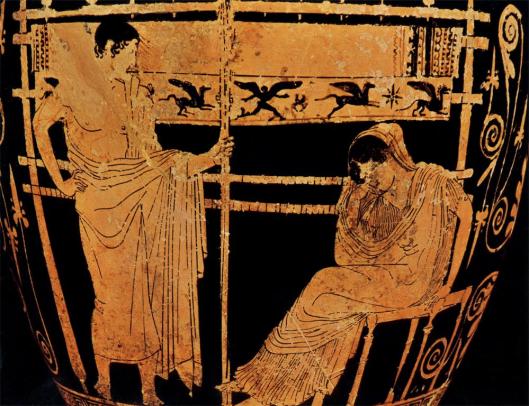

At the beginning of The Lord of the Rings, we find ourselves in a place with a long history, as we see from the many pages of the “Prologue”. It has been a quiet place, but the world outside is becoming less so, with sinister forces growing, as Frodo hears from passing dwarves:

“They were troubled, and some spoke in whispers of the Enemy and of the Land of Mordor.” (The Fellowship of the Ring, Book One, Chapter 2, “The Shadow of the Past”)

In time, readers are brought to see that the dwarves are grossly understating the case: the Enemy is real, Sauron, and that he has not only huge armies, but the Nazgul and a would-be ally in his enemies’ camp, Saruman. The same may be said for the Empire: not only do they have huge fleets and armies, but they have the “ultimate weapon”, the Death Star.

We will learn, as well, that, for all his great age and might, Sauron has an Achilles’ heel: to give the One Ring its power, he has had to pour most of his power into it. Thus, if he regains the ring, he will be much more powerful than he is at present, but, should the ring be destroyed, Sauron will be virtually destroyed with it. As this struggle has been going on in Middle-earth for thousands of years, the idea that Sauron is vulnerable could easily be termed “a new hope”, just as Luke, the son of the Enforcer of the Galaxy, Darth Vader/Anakin Skywalker, will provide a new hope for the Rebels (especially when we are told about “the Chosen One”—for whom he can be taken).

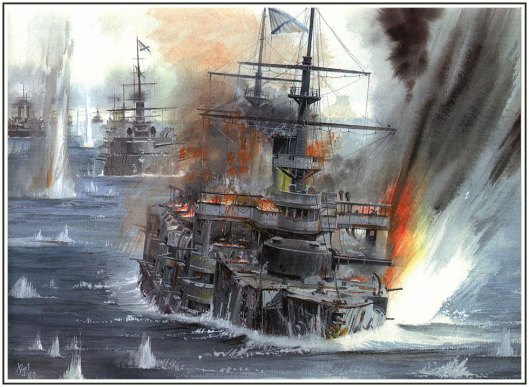

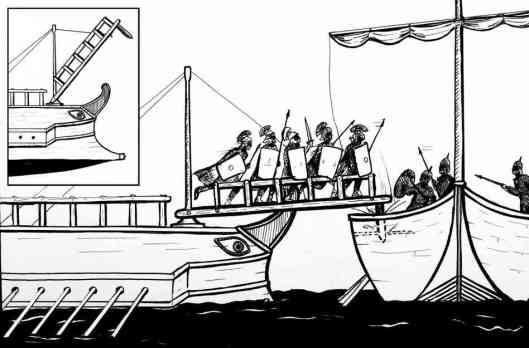

For a time, things do not go well for those opposed to Sauron: he combines psychological/meteorological attacks with the march of huge armies, and even pirate raids on Gondor’s south coast. Gondor is overrun and Minas Tirith is assaulted. This is clearly The Empire Strikes Back, just as the pursuit of the Rebel fleet to Hoth and the destruction of Echo Base disperses the Rebels and casts a shadow over the hope felt after the destruction of the Death Star.

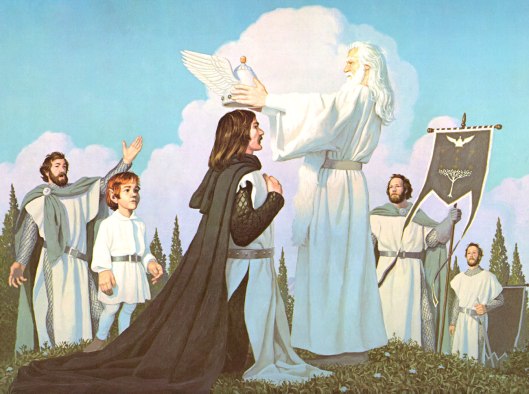

This is not the end, however, for the Rebels or for the good people of Middle-earth. Not only is the Ring destroyed and Sauron disembodied, but this paves the way for The Return of the King, with all of the reflowering-to-come, as we have suggested in a previous posting.

And there is a strong echo in the title of Lucas’ third film, The Return of the Jedi, in which the Emperor is destroyed and balance brought back to the Force—and the galaxy. (Of course, with Star Wars 7, we see that the happy ending is only temporary, but we have hopes that, by the conclusion of 9, there will come a final rebalancing and peace at last.)

Lucas’ acknowledges many sources but, so far, we have yet to locate a quotation from an interview or anywhere else in which he says, “Yes, I’ve read Tolkien closely and, indeed, there is a strong affinity between my work and his”, but we believe that we can suggest, at least, that he, like JRRT, is following the same path in creating a world in turmoil, a visibly-aging world. Into this world, he places his protagonist who provides a new hope, faces the might of a not-easily-defeated enemy, but, by his bravery and determination, finally brings about the destruction of that enemy (interesting in both cases he does not do so himself—Gollum inadvertently destroys the ring, just as Anakin, not his son, kills the Emperor) and the promise of renewal in the return of the Jedi—and the King.

And what do you think, dear readers?

Thanks, as ever, for reading!

MTCIDC

CD