Tags

Blackbeard, Captain George North, Captain Kidd, coins, Doubloon, Edward Teach, Elizabeth I, Hernan Cortez, Inca, Long John Silver, Mexico, Muppet Treasure Island, N.C. Wyeth, Parrot, Pieces of Eight, Pirates, Privateer, reales, Robert Louis Stevenson, Robert Newton, San Luis Potosi, Sir Francis Drake, South America, Spain, Treasure Island, Young Folks

As ever, dear readers, welcome.

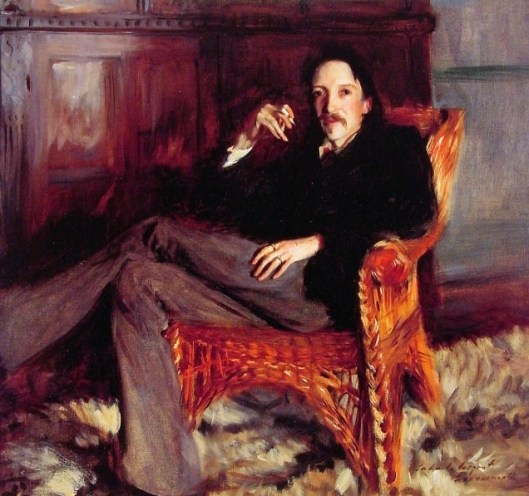

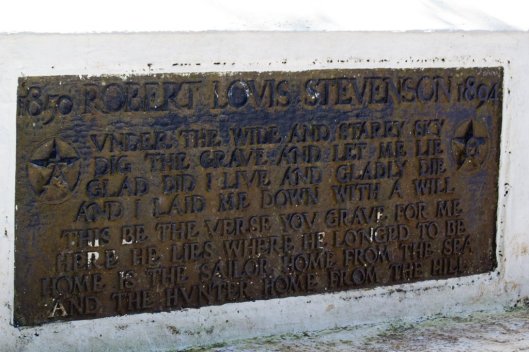

In 1881-1882, a new serial appeared in the British children’s newspaper, Young Folks. Its author was Captain George North and the story was entitled, “Treasure Island or, the Mutiny of the Hispaniola”. In 1883, Cassell and Company published this in book form

as Treasure Island, and its author’s name was right below the title: Robert Louis Stevenson.

The story had come about because Stevenson had seen his stepson, Lloyd, drawing a map. Stevenson joined him and that map became the map.

The book became a number of movies over the years, including one by the Muppets (1996),

but our favorite is that made by the Disney studio in 1950.

This version has Robert Newton as Long John Silver, the man whose twitches and vocal mannerisms have been passed down now as “the way pirates talk” (including—and especially on—“International Talk Like a Pirate Day”, September 19).

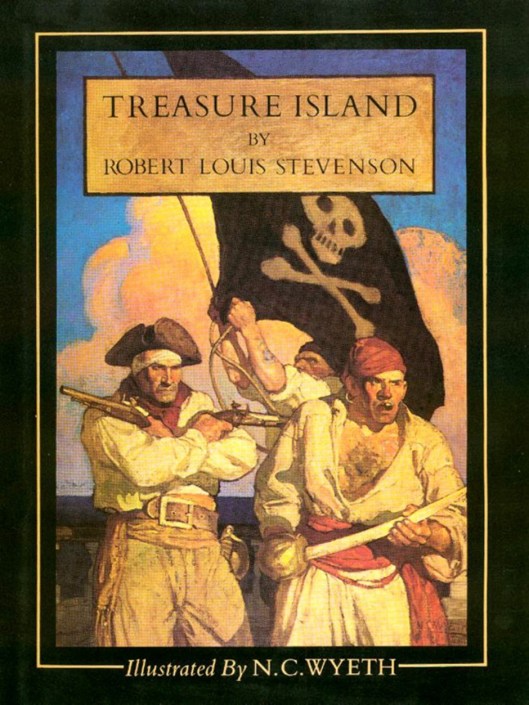

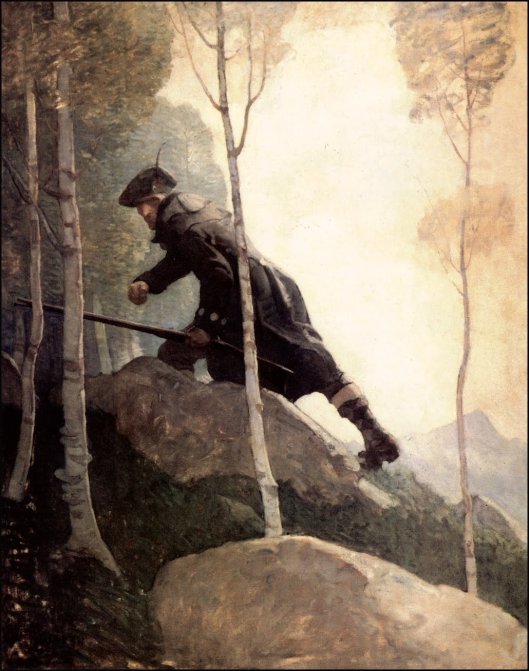

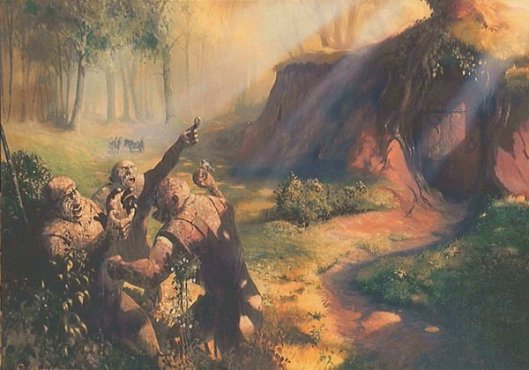

You’ll notice that parrot (as far as we know, there’s no “International Talk Like a Parrot Day”, unfortunately) on his shoulder. We can trace this back to the original novel and identify him as “Captain Flint”, Silver’s pet. Here he is in a picture from our favorite illustrated version, that of NC Wyeth, from 1911.

(If you’d like your own early edition, with Wyeth’s illustrations—not his only pirate pictures, by the way—here’s a LINK to the 1913 printing.)

Among other parrotings, Captain Flint is given to calling “pieces of eight!” and, when we were little, we wondered “pieces of eight what?” and perhaps you did, too. The story begins much earlier than the novel—about 1500. It starts with this early Spanish silver coin called a “real” (14th century).

About 1500, a new coin appeared, worth 8 reales,

and this is a “piece of eight”.

It shouldn’t be confused with another coin Captain Flint might have exclaimed over, the doubloon.

The doubloon (from Spanish “doblon”—“double”) was gold, rather than silver, and was probably called “double” because it was worth two of the coins below, an escudo.

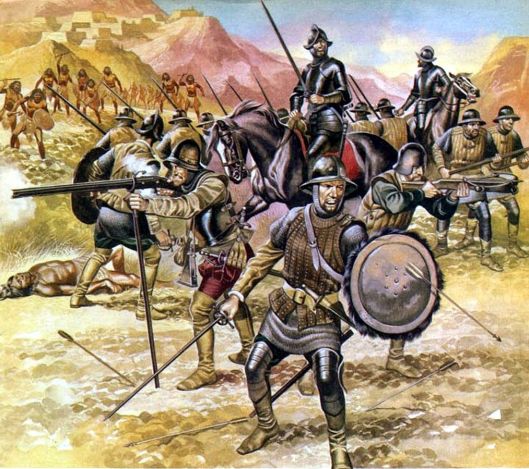

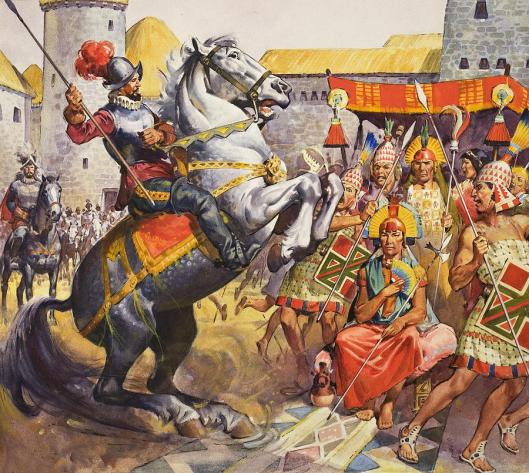

Spanish silver supplies mushroomed after 1519, when a small expedition, led by Hernan Cortez (1485-1547)

landed on the coast of Mexico. The expedition was armed with European weapons and armor of the period.

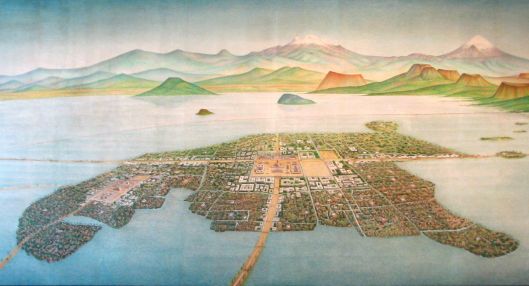

As they marched inland, they found an empire, with a capital set in the middle of a lake, with public buildings made of stone blocks.

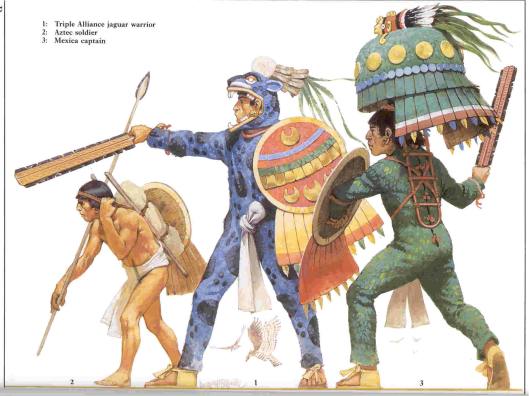

They also found that the local warriors were still living in the Neolithic Era and, though they were fierce, were no match for modern (early 16th-century) weapons.

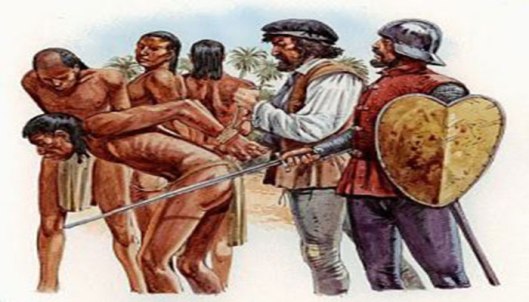

Farther south, other Spanish invaders found the same thing along the west coast of South America,

and soon, they had enslaved the local populations and turned them to work in the silver mines, like that at San Luis Potosi, in Mexico.

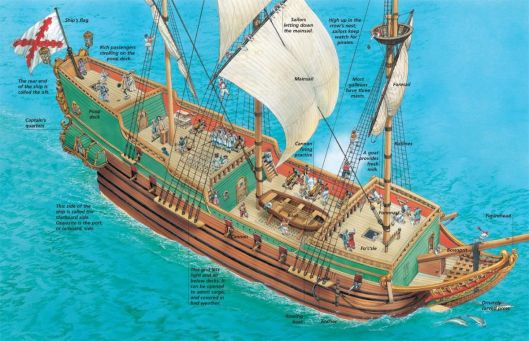

Their labor then produced vast quantities of precious metal, which was left in bars, or turned into coins—pieces of eight and others. This was loaded on ships and sent back to Spain.

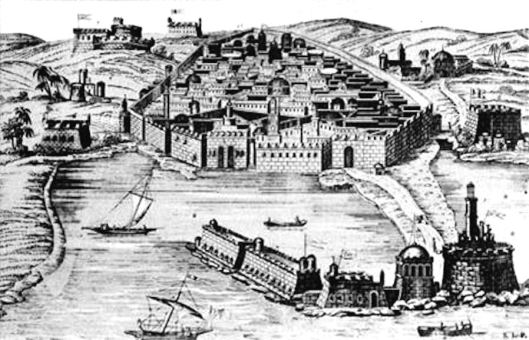

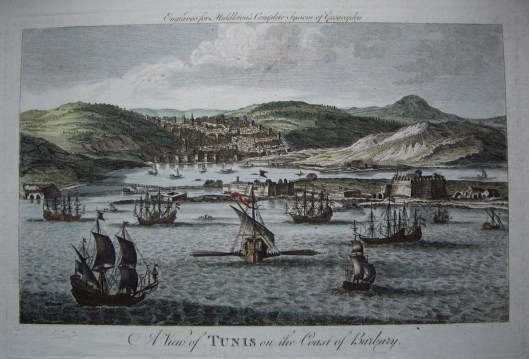

Such riches didn’t escape the attention of Spain’s enemies, however, and soon such ships had to travel in convoys, with merchant ships being shepherded by warships.

This didn’t prevent attacks completely, a famous leader of those attacks being Sir Francis Drake, from the days of Elizabeth I.

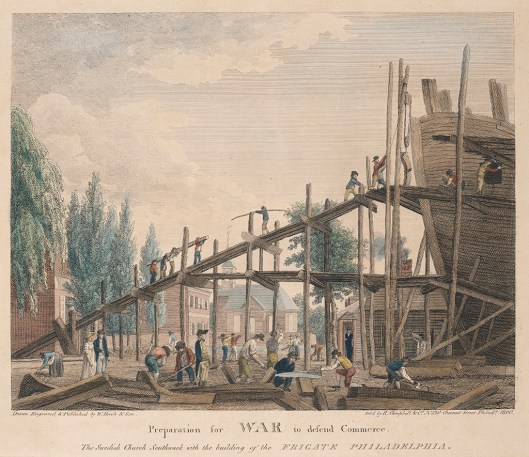

Although the Spanish referred to Drake as a “pirate”, while England was at war with Spain (as it was for much of Drake’s later lifetime), to the English he was a “privateer”—a private naval commander holding a kind of license from Elizabeth I, which permitted him to attack enemy shipping at will (and to share the profits with the Queen’s government). Because he wasn’t one of the government’s official officers, this created a kind of grey area, one which many sailors from western nations, as late as the Napoleonic wars, would take advantage of, slipping between government service and something which, even with that license, could look like piracy. Such men included the notorious, like Captain Kidd

(of whom there is no portrait—we inserted this just for fun)

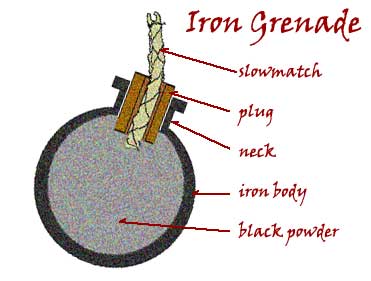

and Edward Teach, “Blackbeard”.

(His beard isn’t really on fire, by the way. He wove bits of matchcord—used to fire ships’ guns and touch off handgrenades—into it to give himself a fiendish aspect.)

Rather than sharing it with governments, both men were said to have taken much of their loot ashore and buried it in now-lost locations—

which brings us back to the map and Captain Flint squawking, “Pieces of eight!”

Thanks, as always, for reading, and definitely

MTCIDC (matey!)

CD

ps

The most famous of Blackbeard’s ships, the Queen Anne’s Revenge, has been located off the coast of North Carolina, here in the US. Here’s a LINK to the site which talks all about the discovery and the ongoing archaeology.