Tags

Baron Dieskau, British, Carillon, Daguerre, Deerfield, Fenimore Cooper's Literary Offenses, Fort Duquesne, Fort Edward, Fort Niagara, Fort St. Frederic, Fort William Henry, French, French and Indian War, General Webb, James Fenimore Cooper, Lake Champlain, Lake George, Lake Ontario, Lt. Col. Munro, Mark Twain, Marquis de Montcalm, Matthew Brady, N.C. Wyeth, Native Americans, Oswego, St. Frederic, The Last of the Mohicans, Ticonderoga

Welcome, dear readers, as always.

This is our 104th posting, making exactly 2 years of maintaining our blog, Doubtfulsea.com. When we began it, we had visited lots of other blogs, but we had no clear idea of what we wanted for ourselves. Our name came from our first novel, Across the Doubtful Sea, available from Amazon and Kindle, but we planned, from the beginning, to cover much more than the subject matter of our novel (among other things, French and English exploration of the Pacific in the 18th century, as well as Polynesian settlement). In consequence, during our two years, we have had postings on a variety of subjects, mostly about adventure/fantasy, often with an historical element, often with a focus upon the work of one of our favorite fantasy authors, JRR Tolkien.

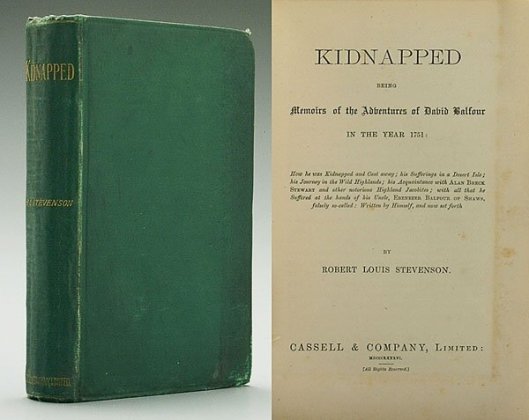

Now, in this last of our second year, we want to look at a person often viewed as the first important American novelist of the early 19th century, James Fenimore Cooper (1789-1851), and his most famous book, The Last of the Mohicans (1826).

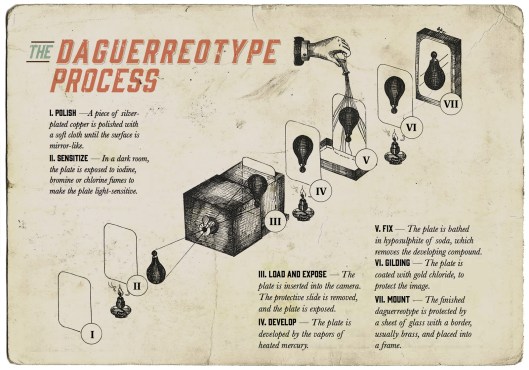

(A footnote: Cooper lived long enough that, the year before his death, he was the subject of an early photograph, using the Daguerre process, by Matthew Brady, 1822-1896, who, in a decade, would become the most famous photographer in the US because of his work documenting the American Civil War, 1861-1865.)

Cooper had a long and very successful career as a novelist, beginning with a social novel, Precaution (1820), but his greatest fame came from his long series based upon US historical subjects and perhaps the most famous of all, that set in the world of the French and Indian War (1754-1763), and the book we want to focus upon,

The Last of the Mohicans.

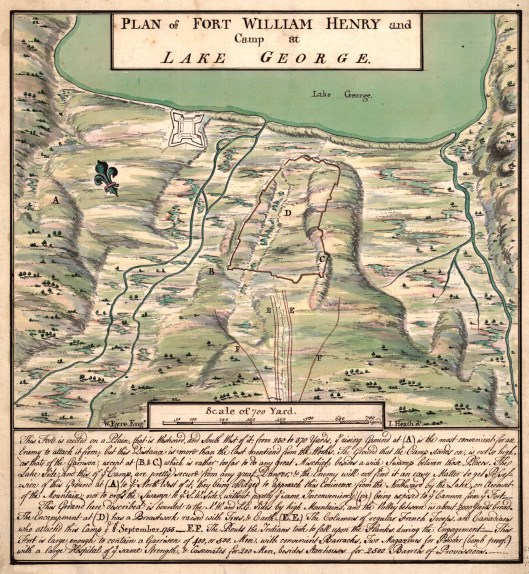

The subtitle, A Narrative of 1757, immediately suggests a specific event of the war, the siege and fall of the British Fort William Henry in August, 1757.

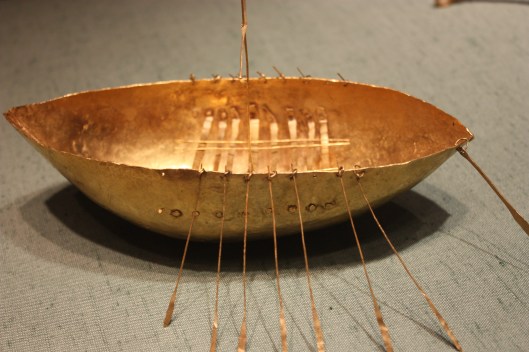

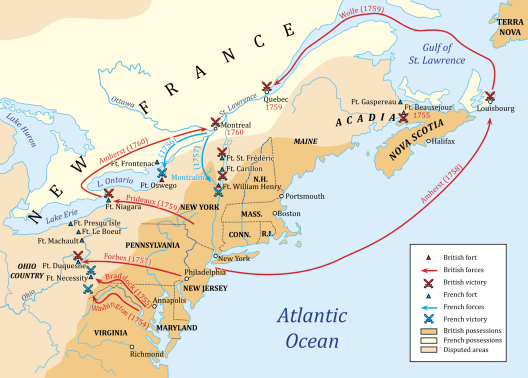

The fort had been built at the head of Lake George as a counterbalance to two French forts, Ticonderoga (called by the French, “Carillon”) and St. Frederic, on Lake Champlain, the lake to the north.

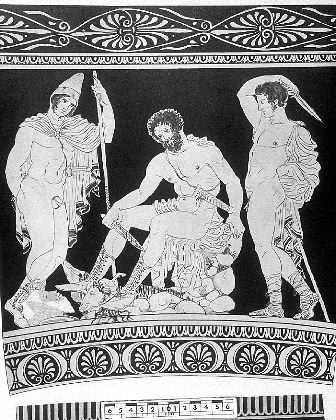

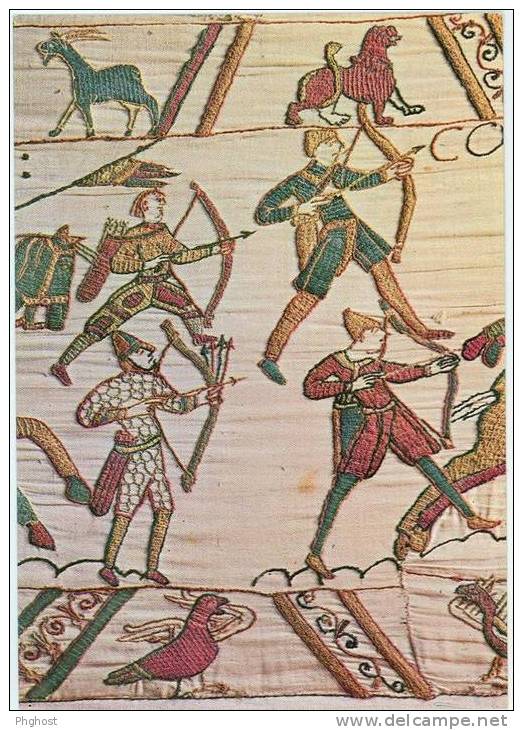

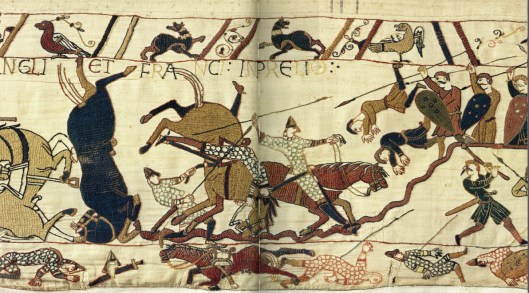

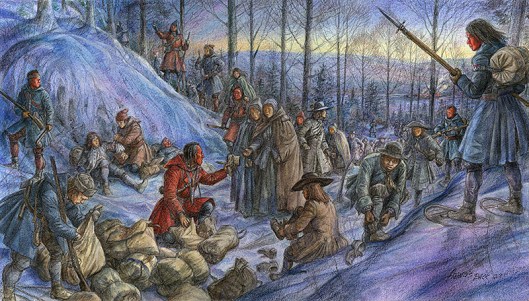

All of these forts—and more—were part of the competition between the British and French to control the northeastern part of North America. This struggle had begun in the later 17th century and had long been a proxy war in which colonial settlers and Native Americans had struggled across many miles of wilderness, raiding each other throughout the years. Here is one of the most famous raids, that of Deerfield in 1704.

In the early 1750s, the French had increased the potential tension by building a new series of forts in what is now western Pennsylvania and eastern Ohio, soon to be countered by British forts.

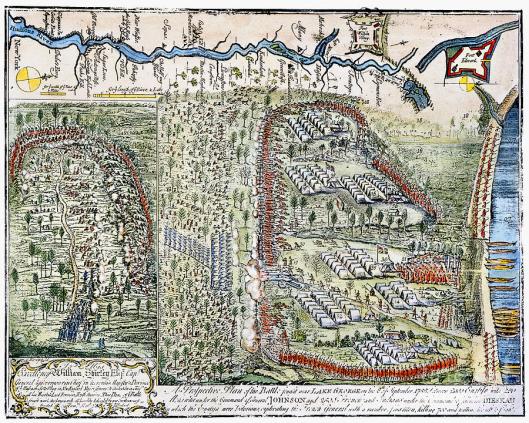

In 1755, as the war heated up, the English planned a three-pronged attack against Ft. Duquesne, Ft. Niagara, and Ft. St. Frederic (called “Crown Point” by the English).

The advance against Ft. Duquesne was defeated, that against Niagara never took off, and that on St. Frederic was blocked by a French attack on the English (actually New England colonial) army at the head of Lake George.

This then became the site of Ft. William Henry.

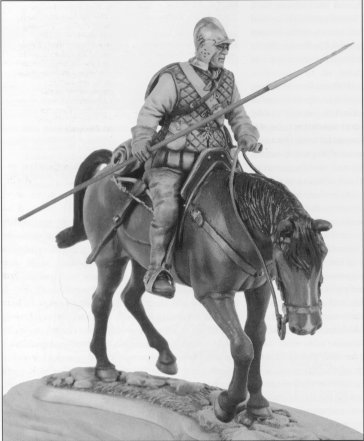

Because the European population of New France was so small in contrast to that of the English colonies—about 70,000 versus more than a million—and because the royal government in Paris had little money to spend (or chose to spend) on the colony, the first two French military commanders, the Baron Dieskau (1701-1767) and the Marquis de Montcalm (1712-1759)

chose an aggressive strategy, aiming to keep the British as far from the center of New France as possible. Although his men were eventually driven off and he was wounded and captured, Dieskau did halt the expedition against Ft. St. Frederic. The next year, 1756, Montcalm destroyed the English forts at Oswego, on the south shore of Lake Ontario, which could have served as staging areas for attacks east and west.

Then, in 1757, he mounted the attack on Ft. William Henry which forms the background story for Cooper’s novel.

To do so, he stripped central New France of its regular troops and militia

and augmented them with Native Americans, for whom he felt no sympathy.

Against such a force, the English commander, Lt. Col. Munro, had a much smaller number of British regulars

and colonial troops, based in the fort itself and in a nearby camp.

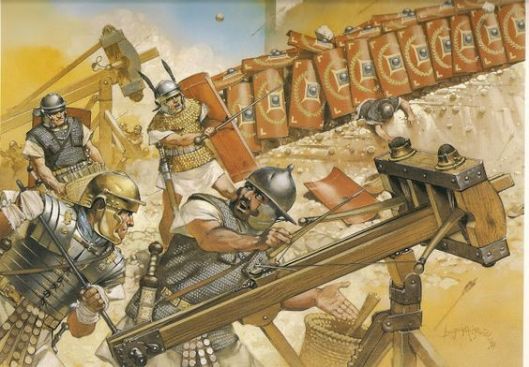

In the 18th century, besieging a town or a fort was a very formal endeavor. Forts and towns were constructed to resist attack, often having multiple walls, ditches, and outer forts, the walls being covered in earth to resist the destructive power of an enemy’s artillery.

Before an attack, the attacker was required to send a messenger in, demanding surrender. In some cases, seeing overwhelming forces and having no promise of relief, a garrison surrendered.

To attack meant beginning with a series of trenches just outside the artillery range of the defenders, then, through zigzagging, to approach closer and closer until:

to approach closer and closer until:

- the attacker’s artillery had knocked a big enough hole in the enemy’s walls that they were rapidly becoming defenseless

- there was the immediate danger of an assault

In the case of Ft. William Henry, there was only a dry ditch, then exposed timber walls.

The French summoned Munro to surrender, he refused, and the French began the siege.

When the French guns had badly damaged the fort and there was no chance of help from General Webb, at Ft. Edward, to the south, Munro surrendered.

Trouble then began when Montcalm’s Native Americans felt cheated of the plunder which they had expected and, when the paroled column of soldiers began to move southward, it was attacked by them. Montcalm and some of his officers intervened, but they were unable to do more than slow the plundering and killing before some 200 fell. (There has been a great deal of argument as to numbers—it appears, for example, that others had been carried away, either to be ransomed later, adopted into tribes, or ritually murdered, as was the custom among some Native American groups. For the best modern account, see Ian Steele, Betrayals, OUP, 1990.)

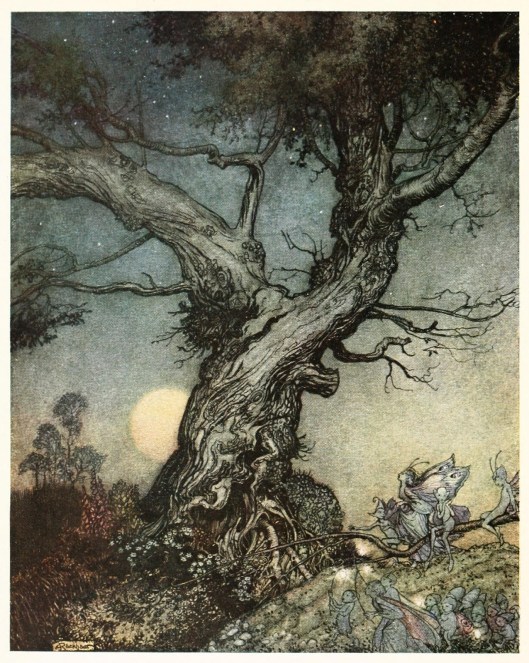

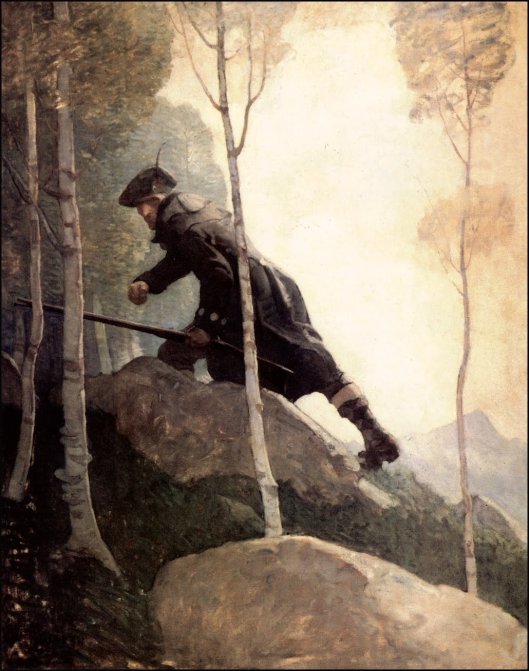

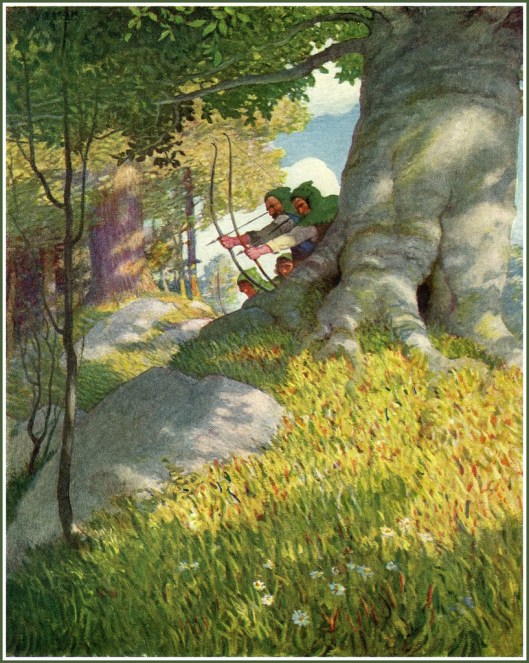

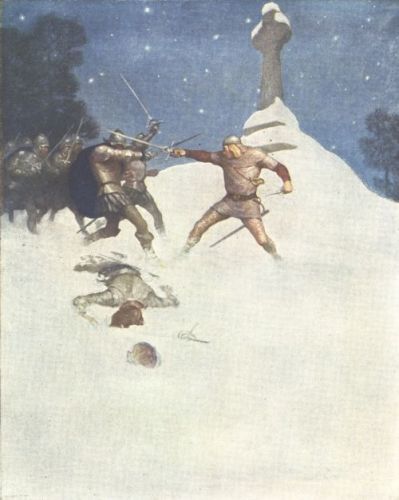

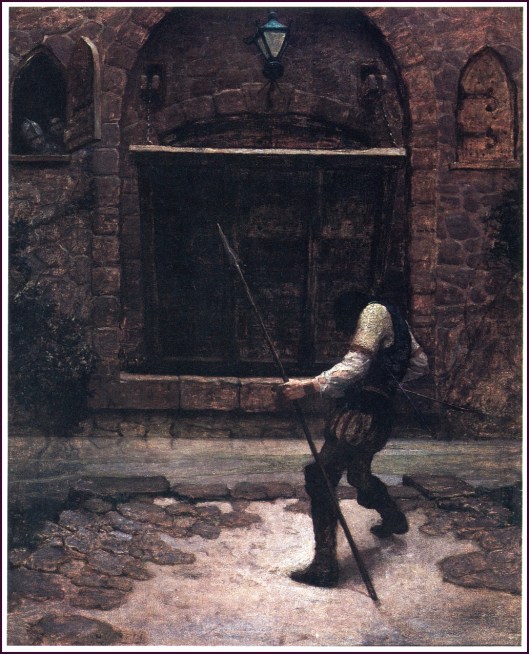

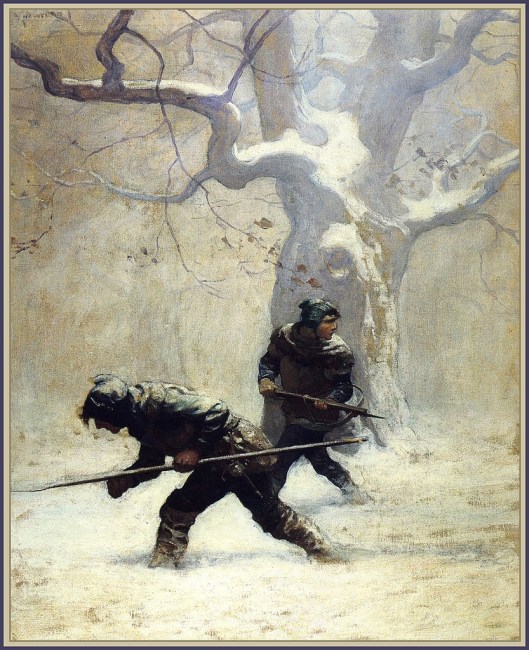

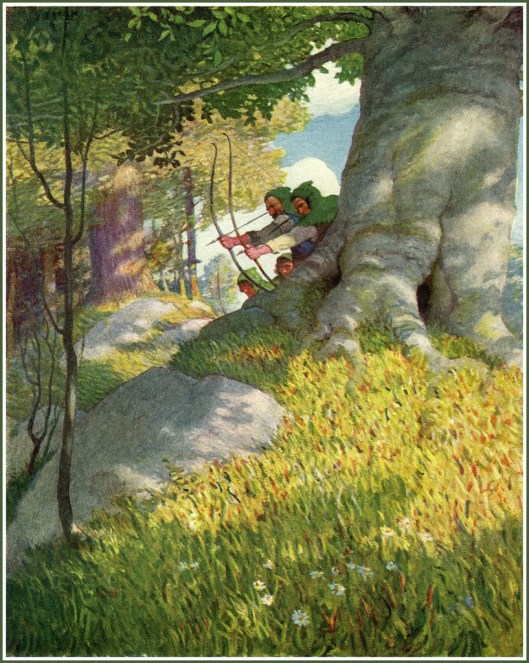

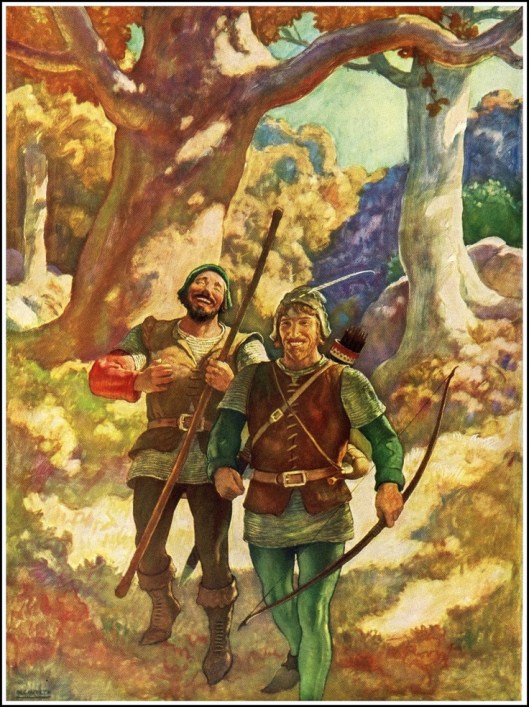

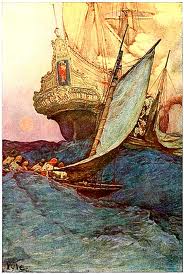

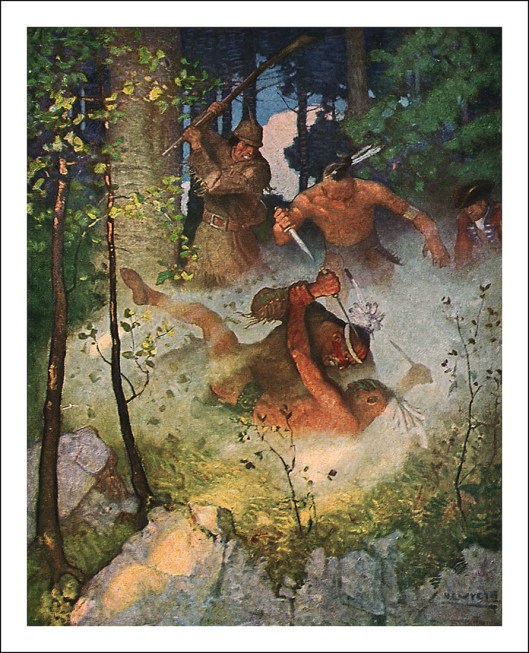

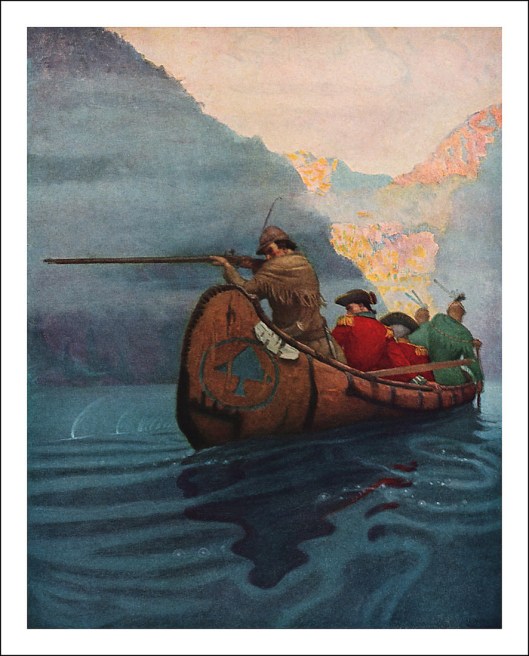

Cooper’s novel, an adventure/romance, uses the fort and siege as its center. Main characters move towards the fort, are in it at the time of the surrender, and are involved in the disaster after it. As might seem inevitable by now, our favorite edition is that illustrated by N. C. Wyeth in 1919.

And here is a selection of the illustrations.

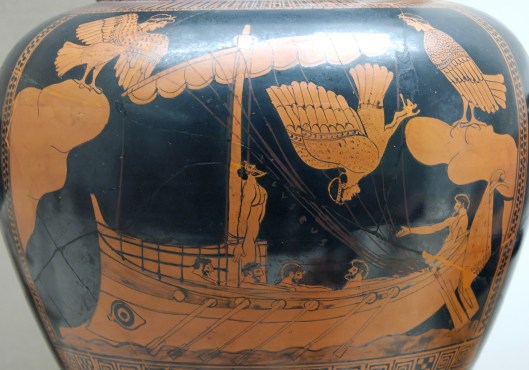

There have been numerous films made of the book, the earliest (at least US one) being a silent, dating from 1912. For us, the most colorful was the one which appeared in 1992, with Daniel Day Lewis as “Nathaniel Poe” (a slight change from the books’ Natty Bumpo). This version made many changes to the original story, including a love interest between Poe and one of Munro’s daughters, Cora, but, for us, it also had four rather spectacular scenes: the ambush of a company of redcoats in the forest by Native Americans,

the French siege of Ft. William Henry,

the British surrender,

and the final “massacre”.

And so we begin our third year of blogging with our next posting. We have, as always, lots of ideas for those postings, which we hope you will enjoy.

Thanks, as always, for reading!

MTCIDC

CD

PS

In 1895, Mark Twain published a comic critique of Cooper’s writing ticks. Entitled, “Fenimore Cooper’s Literary Offenses”, it can be read at http://twain.lib.virginia.edu/projects/rissetto/offense.html.