Tags

American Civil War, Aulos, Crusaders, Great War, Greek, Hoplites, Julius Caesar, Macbeth, Marching song, May 4th, Palestine Song, Rohirrim, Roman songs, songs, Star Wars, Star Wars Day, The Hobbit, The Lord of the Rings, Tolkien, Walter von der Vogelweide

Welcome, dear readers, as always.

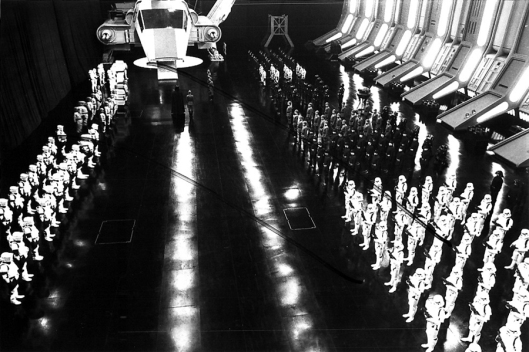

Perhaps because we’re writing this on May the 4th, we’ve been in a musical mood—after all, there’s such a catchy tune involved with it—

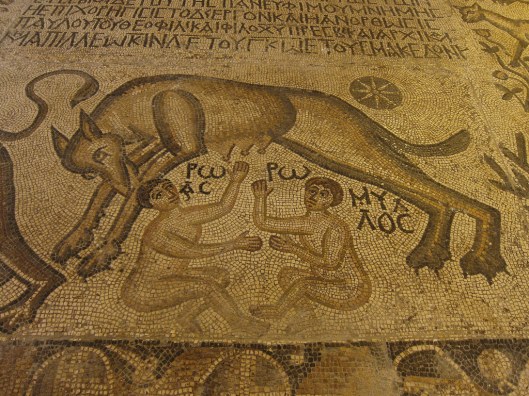

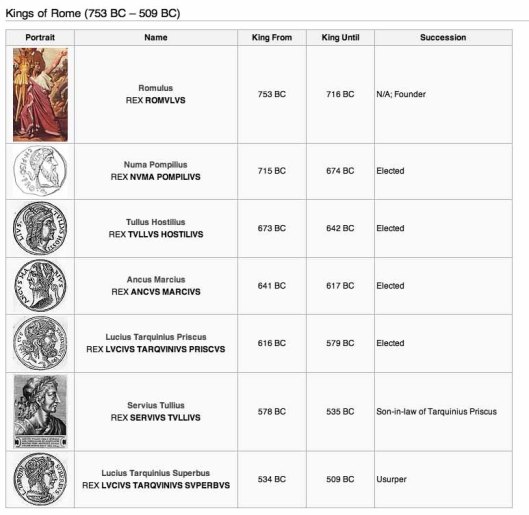

And we wondered if there were words to it? Certainly soldiers have been singing songs seemingly forever. Greek hoplites sang a hymn to Apollo before battle.

(They are accompanied by an aulos player here. “Aulos” is sometimes mistranslated “flute”, but it’s not a kind of recorder. Instead, it’s a member of the oboe family.)

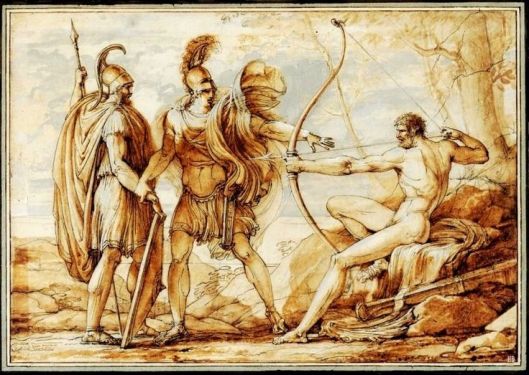

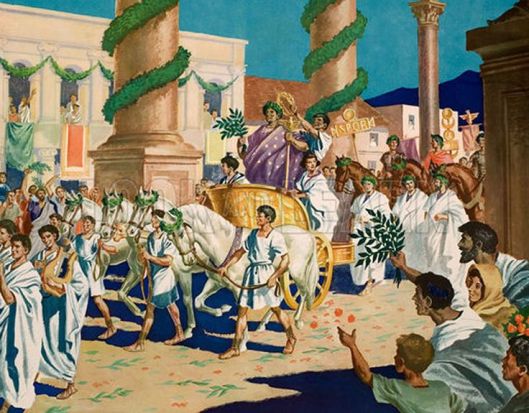

Julius Caesar’s (100-44bc)

soldiers, marching behind his chariot when he celebrated his triumph (formal victory parade) in Rome

sang an unprintable song about his sex life. There’s only a fragment surviving and we’ll print it here—but in Latin—a typical Victorian thing to do.

“Urbani, servate uxores: moechum calvom adducimus.

Aurum in Gallia effutuisti, hic sumpsisti mutuum.”

(Here’s a LINK which we would recommend about reconstructing Roman soldiers’ songs.)

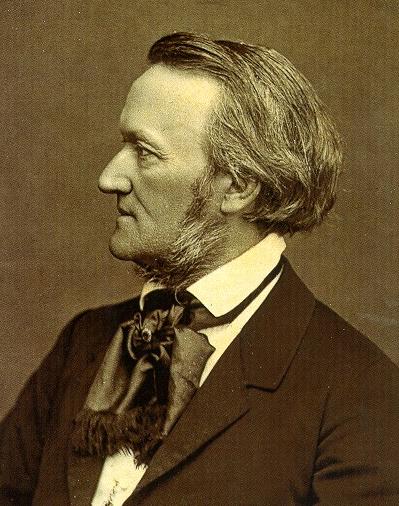

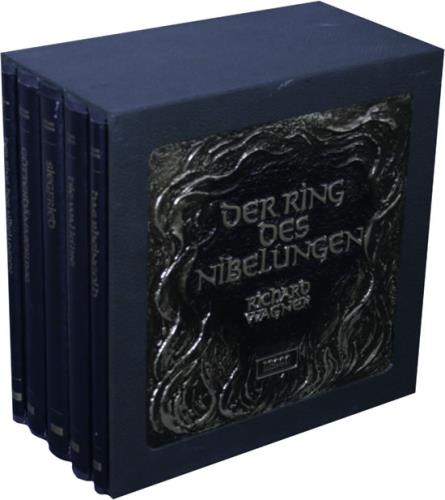

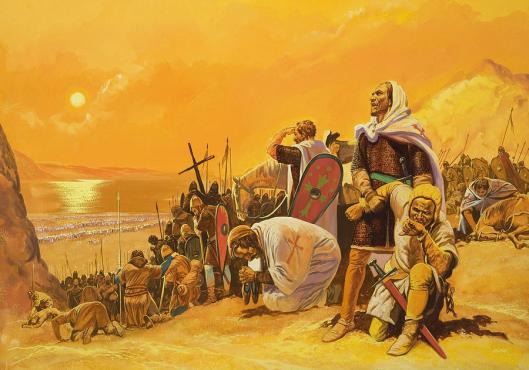

There’s a stirring piece by Walter von der Vogelweide (c.1170-c.1230),

called the “Palestine Song”, supposedly sung by a crusader after reaching the Holy Land. We can imagine later Crusaders singing it as they marched

As in the case of the Caesar fragment, however, we won’t print the text—we aren’t enthusiastic about crusades, especially the medieval ones, believing them to have been the drawn-out attempt at a massive landgrab of places already long-inhabited.

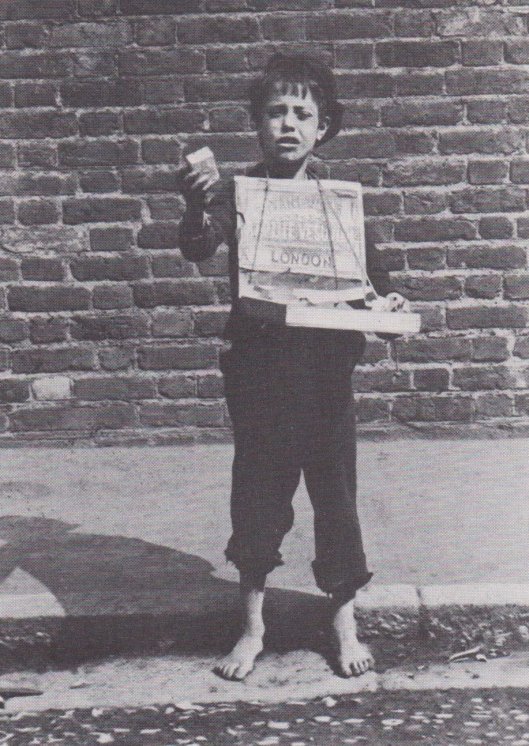

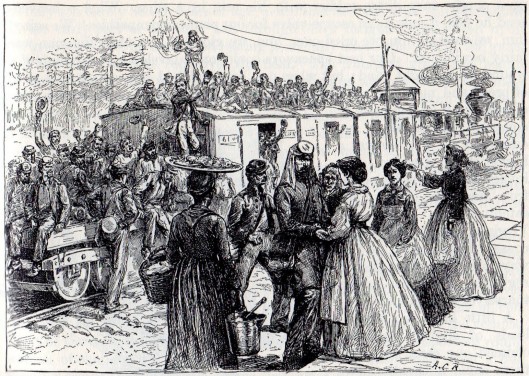

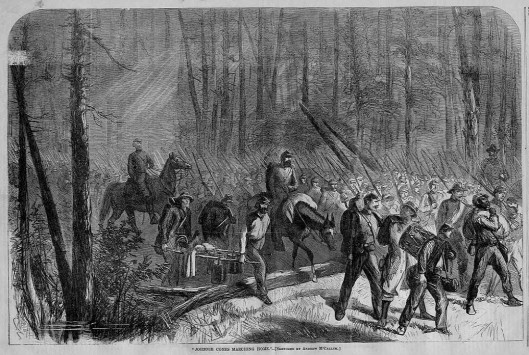

On long, monotonous marches, we imagine soldiers always sang. The American Civil War was fought over hundreds of miles and, with the rare exception when trains could be used,

soldiers walked everywhere.

That being the case, it’s no wonder that so many of their favorite songs had the word “marching” in the title.

(And that last one’s chorus begins, “Tramp, tramp, tramp, the boys are marching…”)

Russian soldiers appear to have had designated regimental singers, who, when called, hurried up to the front of the column and broke into choruses to keep up the men’s spirits on long journeys.

(We apologize that these Russians aren’t singing—but this is, in fact, a film of the last czar, Nicholas II, reviewing his guards just before the Great War, so, at least, they’re marching.)

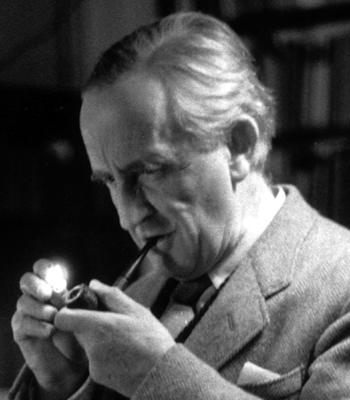

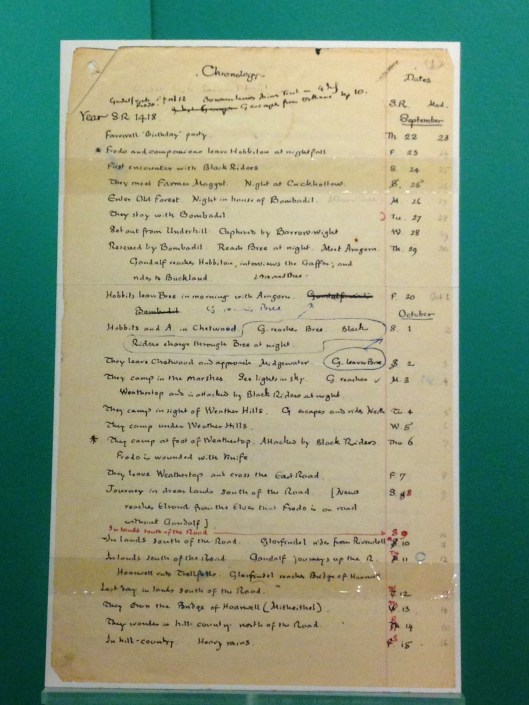

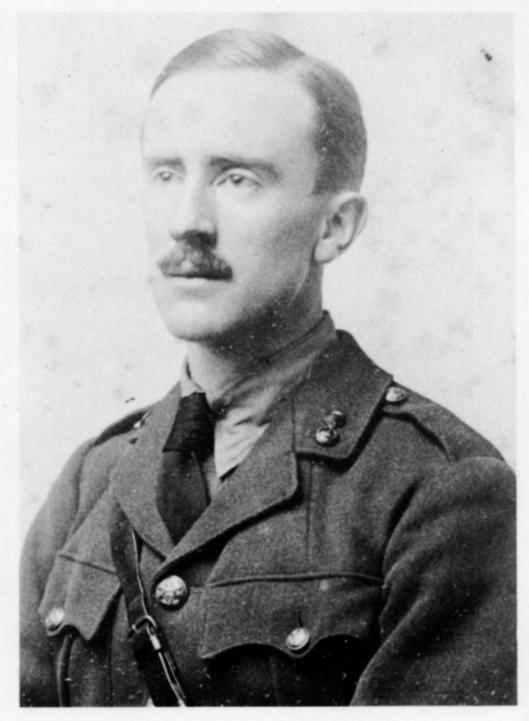

Which brings us to the Great War and our own officer in it, JRRT.

Certainly, the soldiers in his battalion (13th, Lancashire Fusiliers)

would have sung—here are two popular favorites—

There were other songs, too, but not cheery at all, and officers were instructed to discourage their singing. The words of one, sung to the tune of “Auld Lang Syne”, expressed the terrible monotonous nature of trench warfare, being only “We’re here because we’re here because we’re here because we’re here”. A second, “Hangin’ On the Old Barbed Wire”, as it was called, had a mocking little tune, like something from a music hall, but described the whereabouts of soldiers who, for various reasons, were out of the firing line—until it came to the last verse:

“If you want the old battalion,

I know where they are, I know where they are, I know where they are

If you want to find the old battalion, I know where they are,

They’re hanging on the old barbed wire,

I’ve seen ’em, I’ve seen ’em, hanging on the old barbed wire.

I’ve seen ’em, I’ve seen ’em, hanging on the old barbed wire.“

Here’s a LINK, if you’d like to hear an abbreviated version. In this , the group, Chumbawamba, uses an alternative line, “If you want to find the private”, but both versions are grim—and we presume that Tolkien knew all of these songs and many more, some, like the song about Julius Caesar, completely unprintable!

(Our image, by the way, is of a wiring party from the 1st Battalion, Lancashire Fusiliers. Those curly things, called “screw pickets”, you see resting on the front man’s right shoulder are the stakes which were twisted into the ground and then barbed wire was run through them and wrapped around them. Here’s an early US WW2 picture of a soldier working with the upper loops of one.)

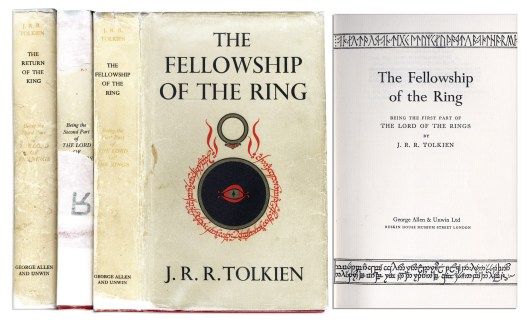

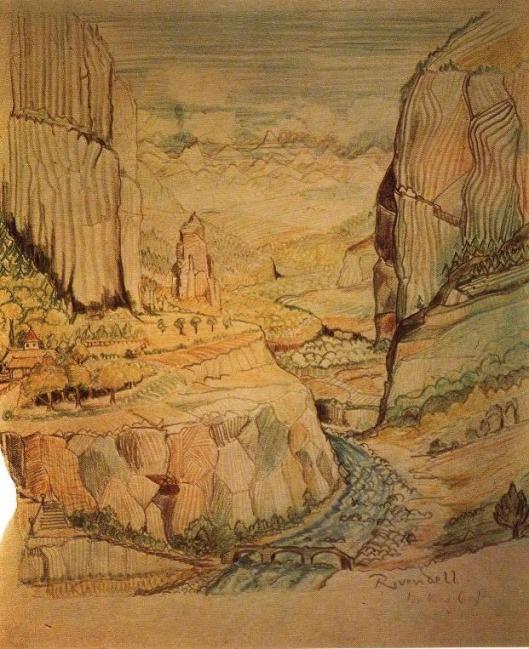

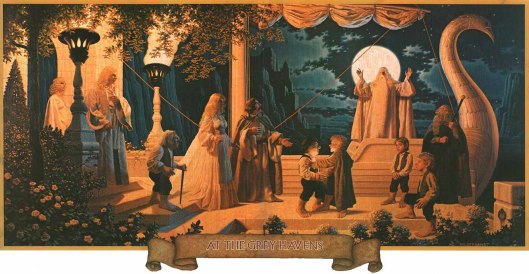

As we’ve often discussed before, things from JRRT’s real life sometimes have a way of seeping into his fiction, and we can certainly see it here.

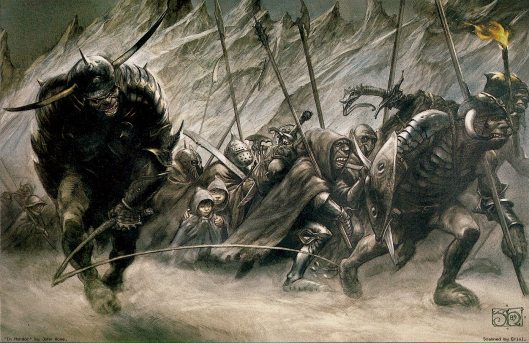

Although they’ve been silent on the march, on their way to the attack, the Rohirrim, for example, are far from that:

“And then all of the host of Rohan burst into song, and they sang as they slew, for the joy of battle was on them, and the sound of their singing that was fair and terrible came even to the City.” (The Return of the King, Book Five, Chapter 5, “The Ride of the Rohirrim”)

Unfortunately, we have no idea what their songs might have been like—perhaps they would have resembled Theoden’s cry to the Rohirrim:

“Arise, arise, Riders of Theoden!

Fell deeds awake: fire and slaughter!

Spear shall be shaken, shield be splintered,

A sword-day, a red day, ere the sun rises!

Ride now, ride now! Ride to Gondor!”

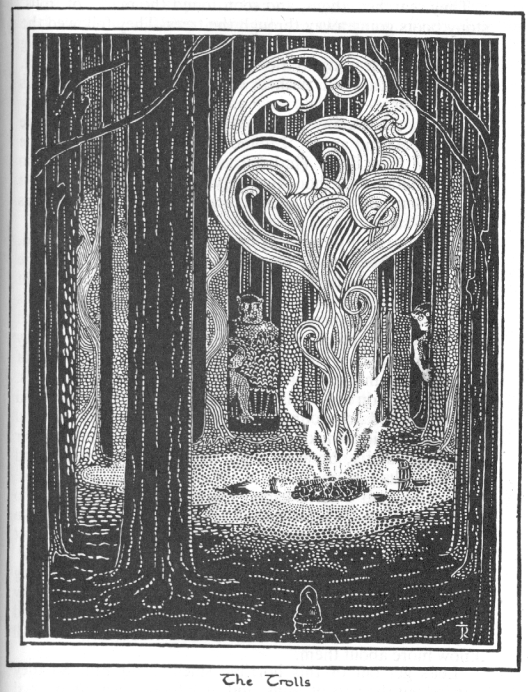

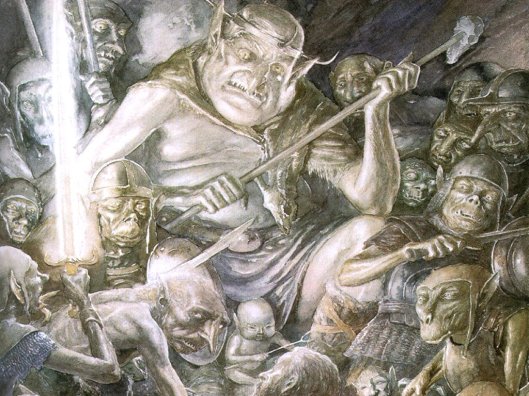

Oddly, we do have two of what might be called Goblin marching songs,

both from The Hobbit. The first is sung right after the dwarves are captured in a cave in which they’ve taken shelter in the Misty Mountains.

“Clap! Snap! the black crack!

Grip, grab! Pinch, nab!

And down down to Goblin-town

You go, my lad!

Clash, crash! Crush, smash!

Hammer and tongs! Knocker and gongs!

Pound, pound, far underground!

Ho, ho! my lad!

Swish, smack! Whip crack!

Batter and beat! Yammer and bleat!

Work, work! Nor dare to shirk,

While Goblins quaff, and Goblins laugh,

Round and round far underground

Below, my lad!”

(Chapter Four, “Over Hill and Under Hill”)

The second appears two chapters later, when the company is trapped in the pines and the Goblins and Wargs are below:

“Burn, burn tree and fern!

Shrivel and scorch! A fizzling torch

To light the night for our delight

Ya hey!

Bake and toast ’em, fry and roast ’em!

till beards blaze, and eyes glaze;

till hair smells and skins crack,

fat melts, and bones black

in cinders lie

beneath the sky!

So dwarves shall die,

and light the night for our delight,

Ya hey!

Ya-harri-hey!

Ya hoy!”

(Chapter Six, “Out of the Frying-pan Into the Fire”)

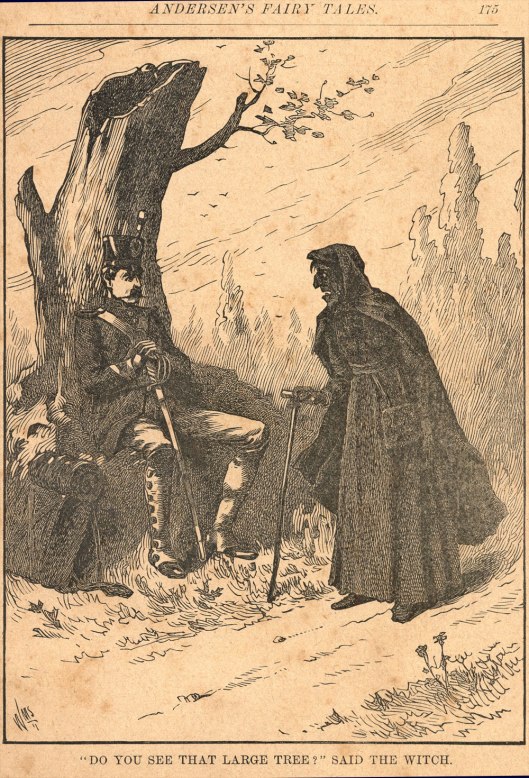

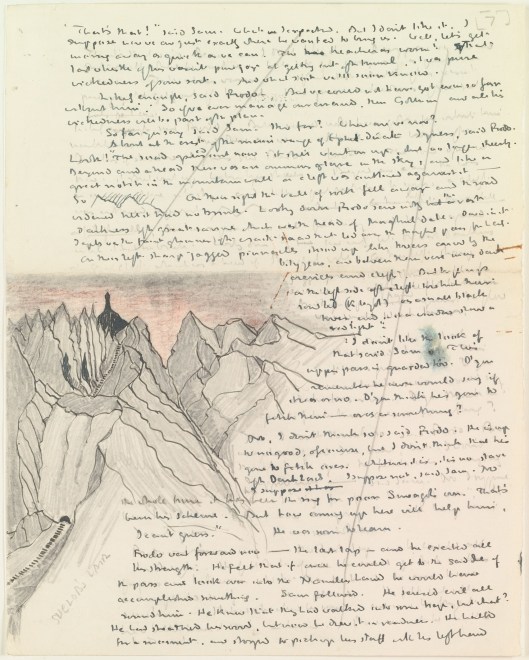

We notice that the opening of the second bears a certain resemblance to another song sung in a wild location—by wild people:

“First Witch

Round about the cauldron go;

In the poison’d entrails throw.

Toad, that under cold stone

Days and nights has thirty-one

Swelter’d venom sleeping got,

Boil thou first i’ the charmed pot.

All

Double, double, toil and trouble; (10)

Fire burn, and cauldron bubble.

Second Witch

Fillet of a fenny snake,

In the cauldron boil and bake;

Eye of newt and toe of frog,

Wool of bat and tongue of dog,

Adder’s fork and blind-worm’s sting,

Lizard’s leg and howlet’s wing,

For a charm of powerful trouble,

Like a hell-broth boil and bubble.”

(Macbeth, Act 4, Scene 1)

In The Lord of the Rings, JRRT blurs Goblins and orcs and, considering that we almost always see orcs as moving in companies, we’ll see them that way, too, marching across Rohan or on the stone roads of Mordor, and we’d like to imagine that they, too, have songs to make the way shorter. But what do they sing about? And, judging by the Goblin’s songs, do we want to know?

Thanks, as always, for reading and

MTCIDC

CD

ps

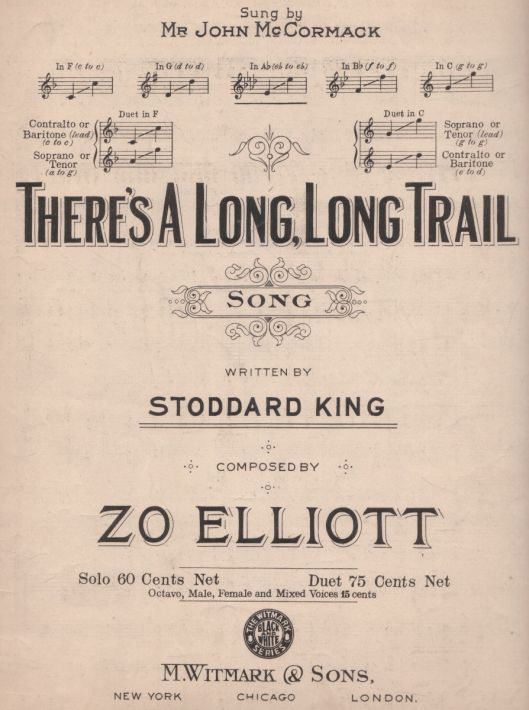

Another Great War soldiers’ song was more melancholy than sarcastic, although it still suggested marching,

and, when you read the chorus, you’ll see why.

Here’s a LINK of it sung by a famous tenor of that time, John McCormack (1884-1945) and here are soldiers at a happier moment and we hope that Tolkien sometimes saw them this way, too.