Tags

Argonautica, Bilbo, Bree, Fantasy, Frodo, Gondor, Great East Road, Jason, Journey to the West, lotr, Tharbad, The Argonautica, The Bridge of Strongbows, the Greenway, The Hobbit, The Lord of the Rings, The Odyssey, the-great-east-road, Tolkien, Willie Nelson

“Just can’t wait to get on the road again

The life I love is makin’ music with my friends

And I can’t wait to get on the road again

And I can’t wait to get on the road again”

As always, welcome, dear readers. This is from a Willie Nelson, a US country and western singer’s,

virtual theme song, and it seemed to fit where this posting wanted to go.

Having just written two postings about traveling to Bree, it struck me just how many Western adventure stories, as a main element of the plot, require the characters to travel, often long distances. (I’m sure that there are lots of Eastern stories which do this, too—see, for example, Wu Cheng’en’s (attributed) Journey to the West, which appeared in the 16th century—see, for more: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Journey_to_the_West You can read an abridged translation of this at: https://www.fadedpage.com/books/20230303/html.php )

Such adventures are commonly quests—that is, journeys with a particular goal and are commonly round- trip adventures. (For more on quests, see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Quest )

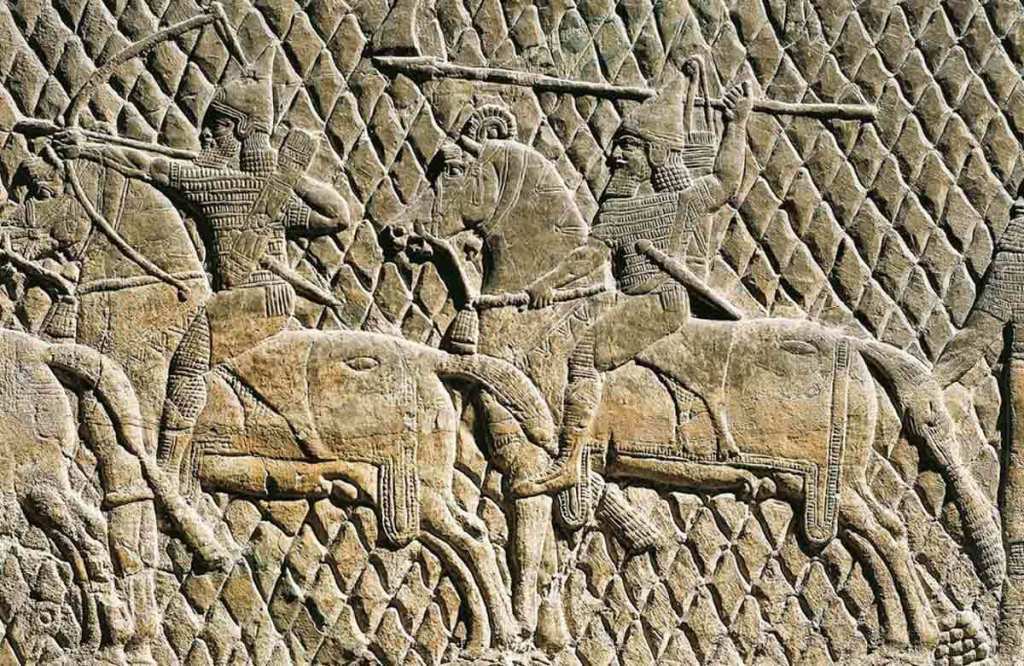

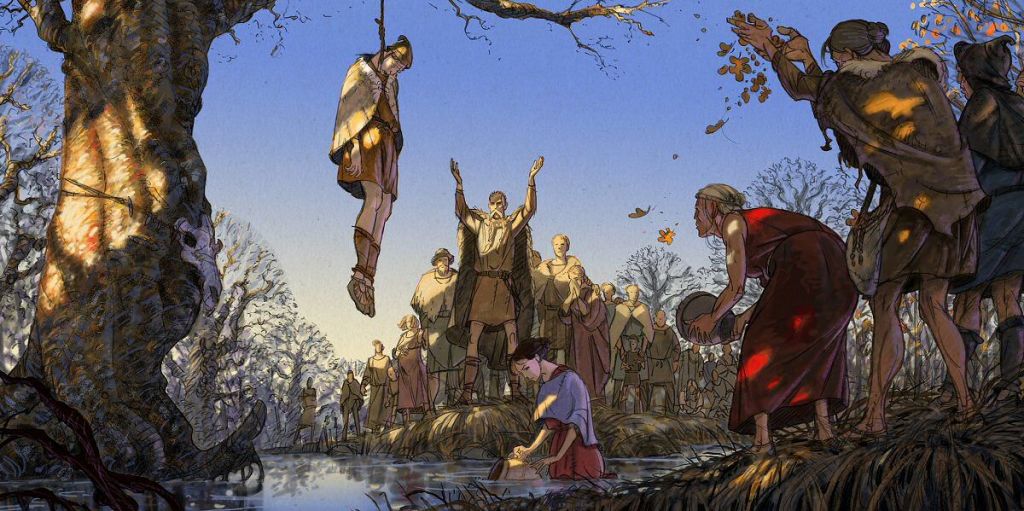

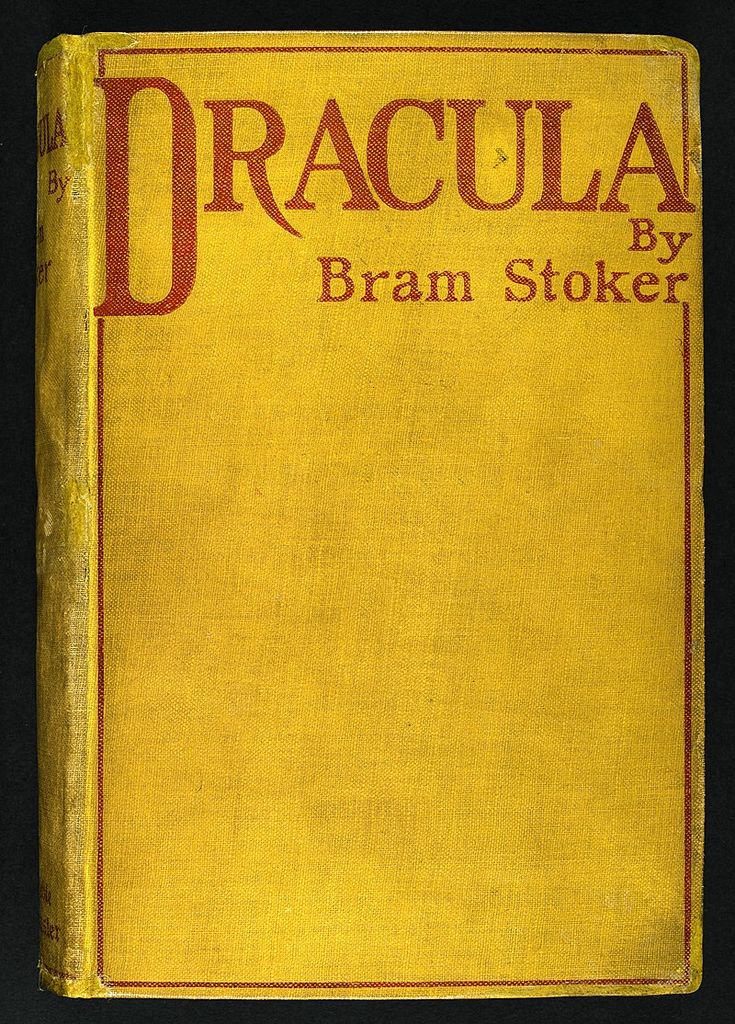

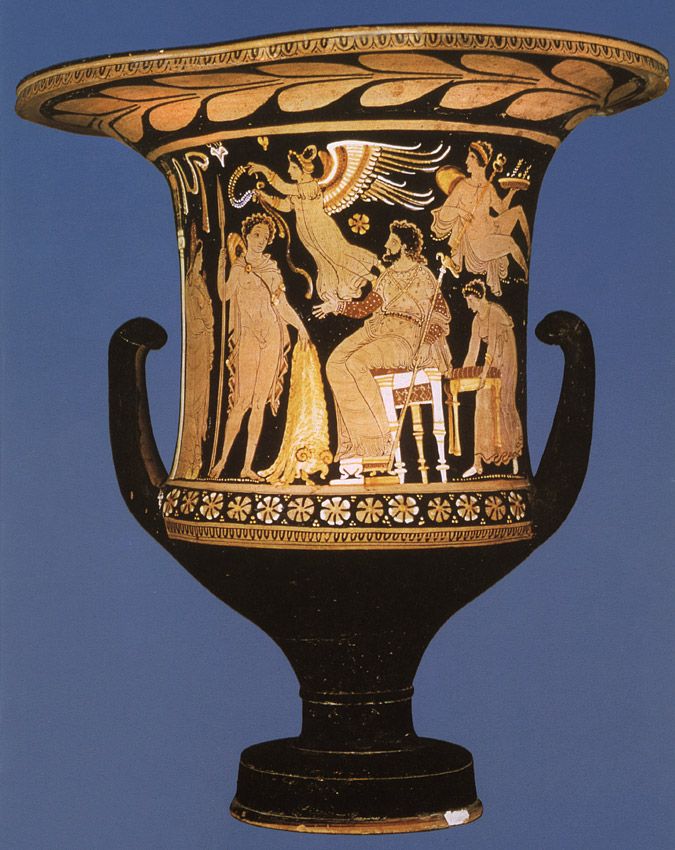

There are lots of folktales with this pattern, but the literary begins for us with the story of Jason, and his task of finding the Golden Fleece and bringing it back to Greece. (You can read a summary of the story here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Golden_Fleece The full Greek version we have of the story is from a 3rd century BC poem, the Argonautica of Apollonius of Rhodes, which you can read in a translation here: https://archive.org/details/apolloniusrhodiu00apol And you can read about the poem itself here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Argonautica )

(Jason delivering the fleece to King Pelias—for more on Pelias, who is actually Jason’s uncle, see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pelias )

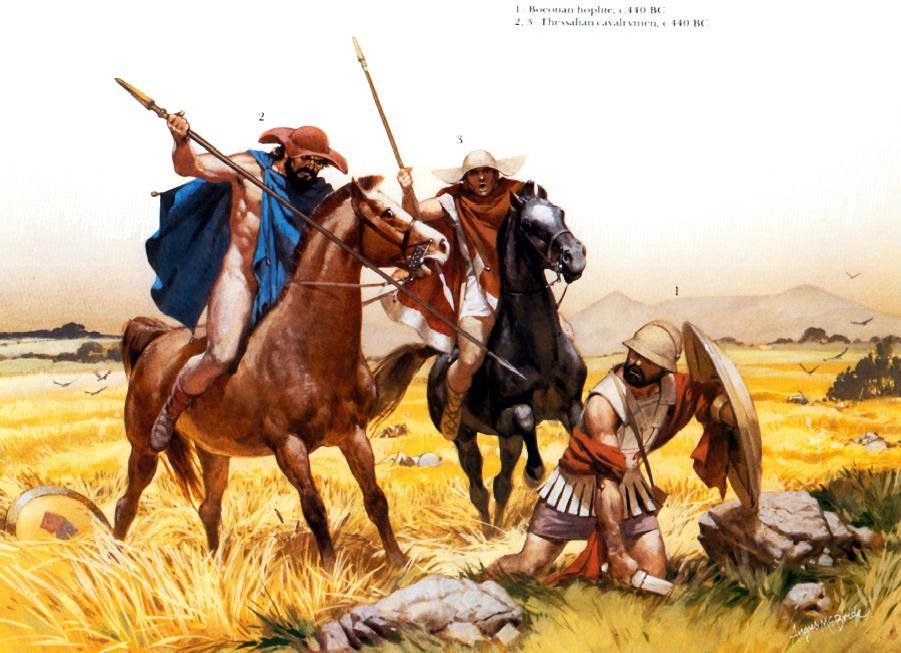

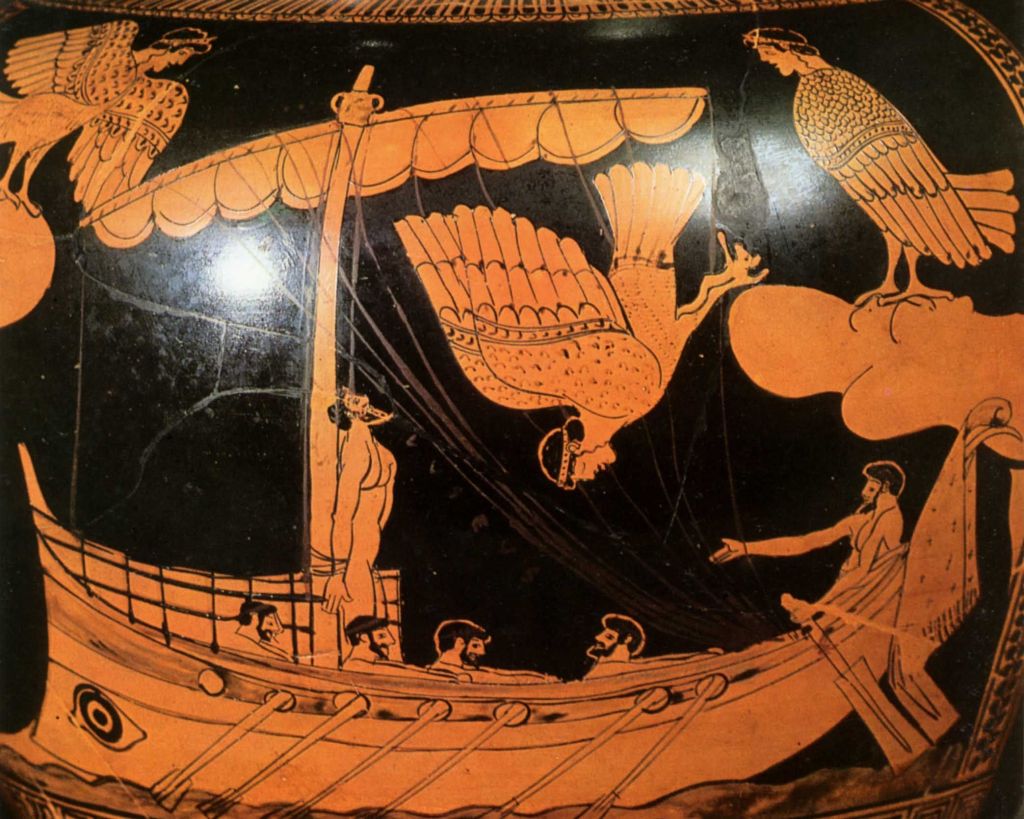

Then there’s the Odyssey, a later story, in mythological time, in which the main plot is that of Odysseus, a Greek and ruler of the island of Ithaka, who, having participated in the war against Troy, spends 9+ years of many adventures getting home to his island once more.

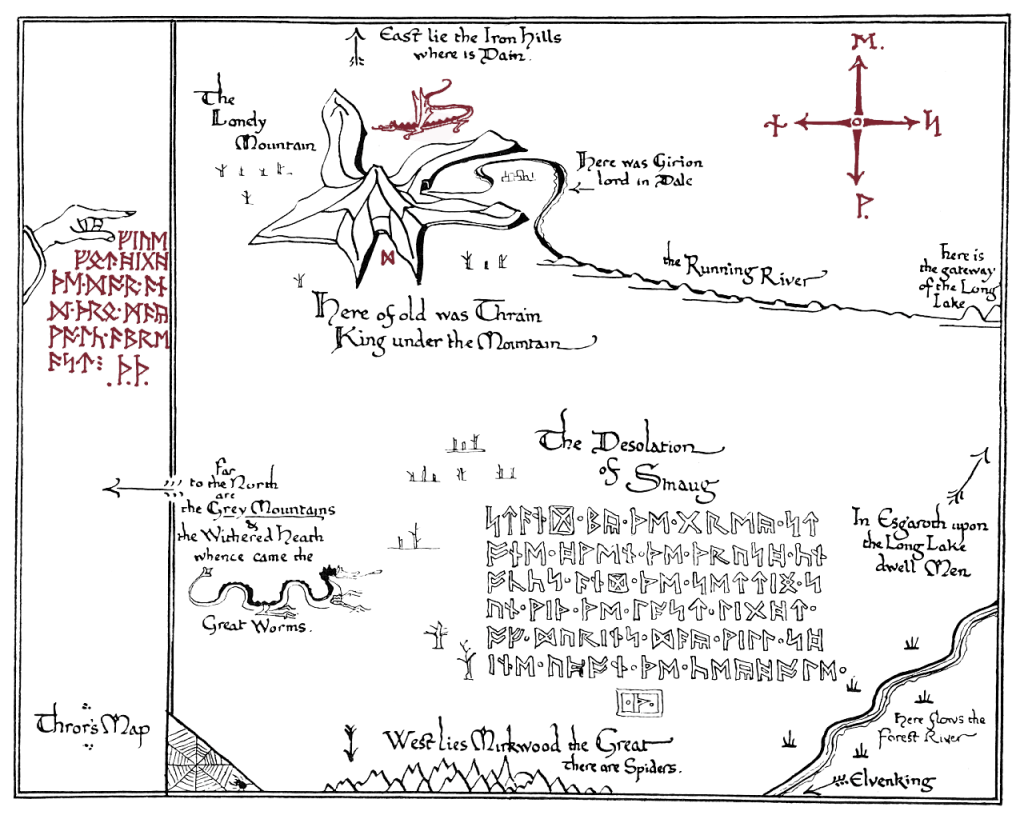

It’s no wonder, then, that Tolkien, originally destined to be a classicist, in telling a long story to his children, would make it a quest.

This quest would take the protagonist, Bilbo Baggins, from his home in the Shire hundreds of miles east, to the Lonely Mountain (Erebor) and back.

(Pauline Baynes—probably JRRT’s favorite illustrator—and whom he recommended to CS Lewis, for whom she illustrated all the Narnia books. You can read about her here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pauline_Baynes )

In the last two postings, we first followed Bilbo eastwards to Bree—only to find that, in The Hobbit, there is no Bree. We then retraced our steps and followed Frodo and his friends as they journeyed in the same direction, although this time with more success.

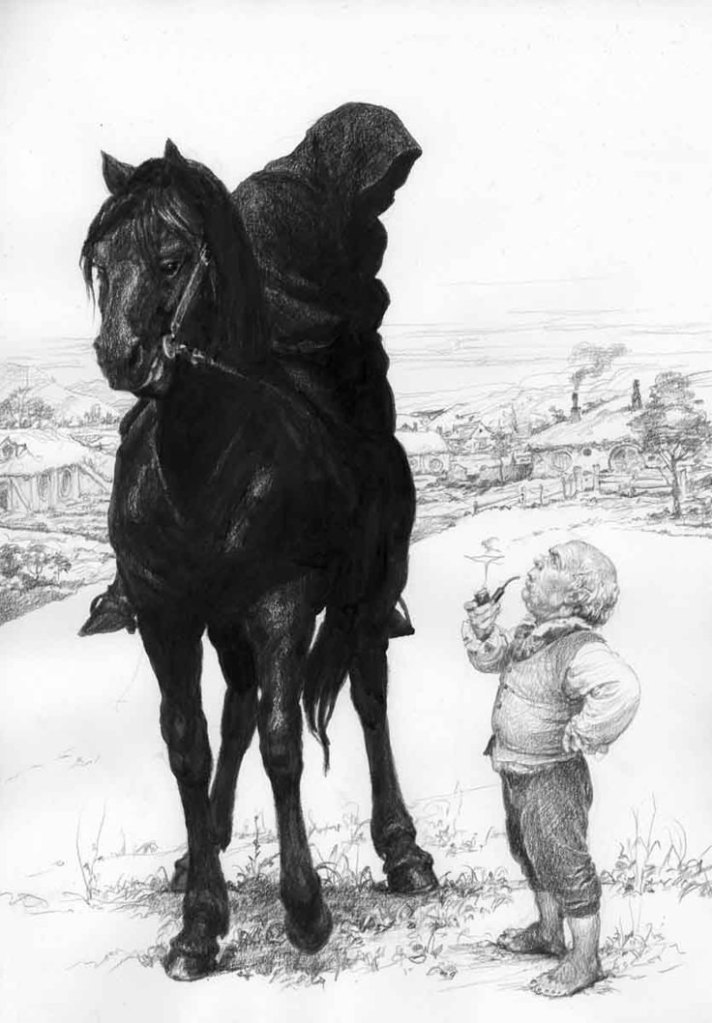

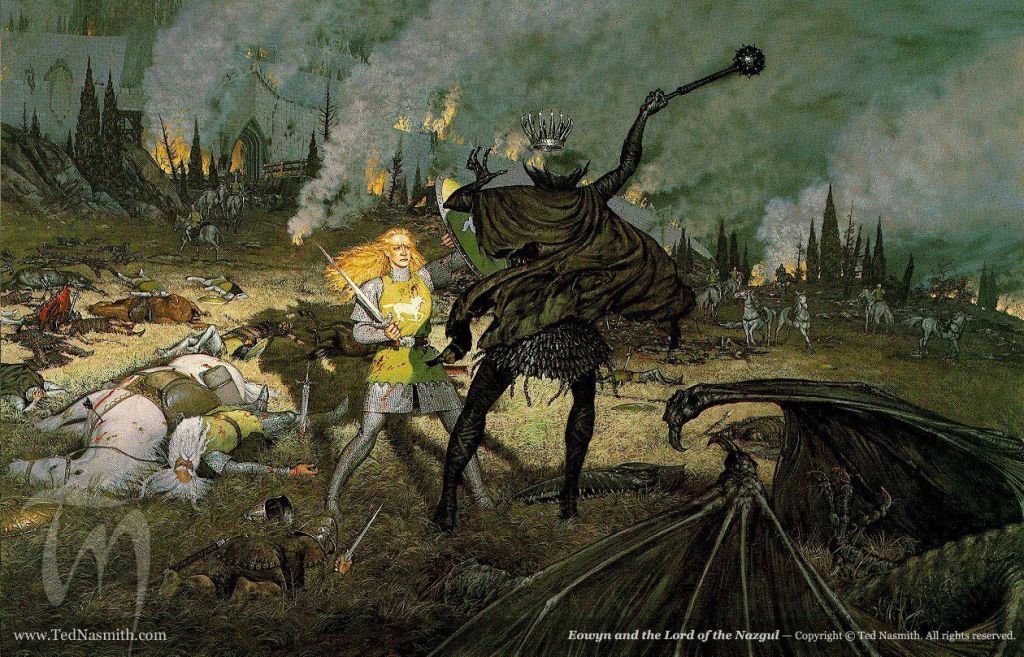

(Ted Nasmith)

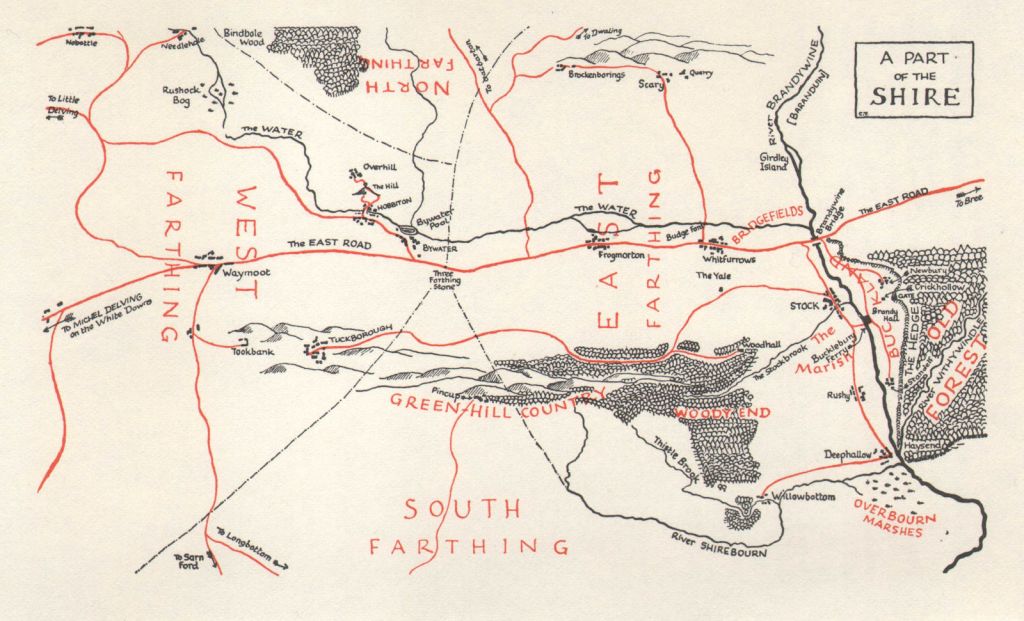

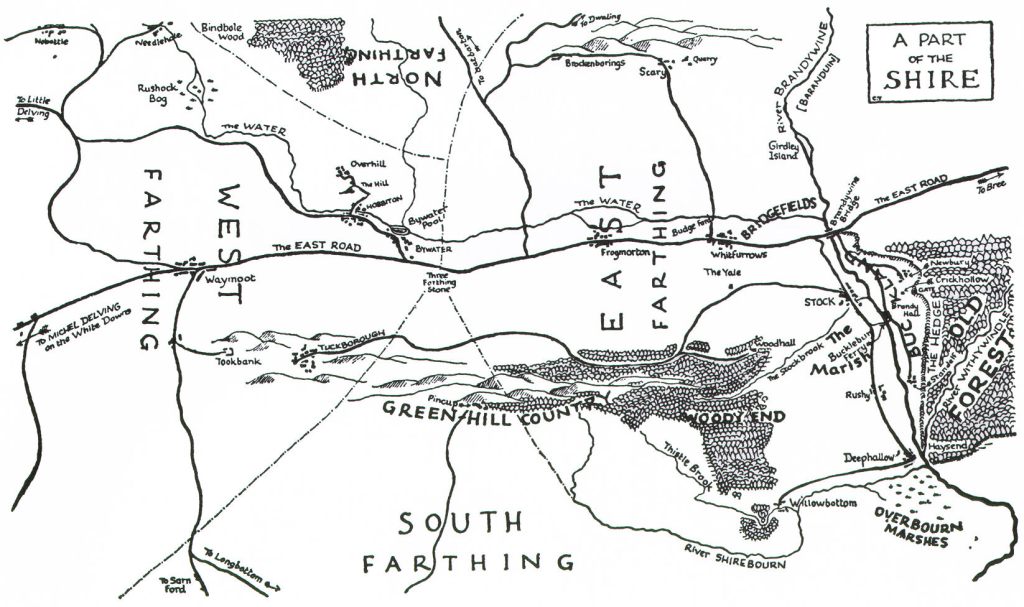

Part of Frodo’s trip (with some detours), took him along the Great East Road, which ran through the Shire,

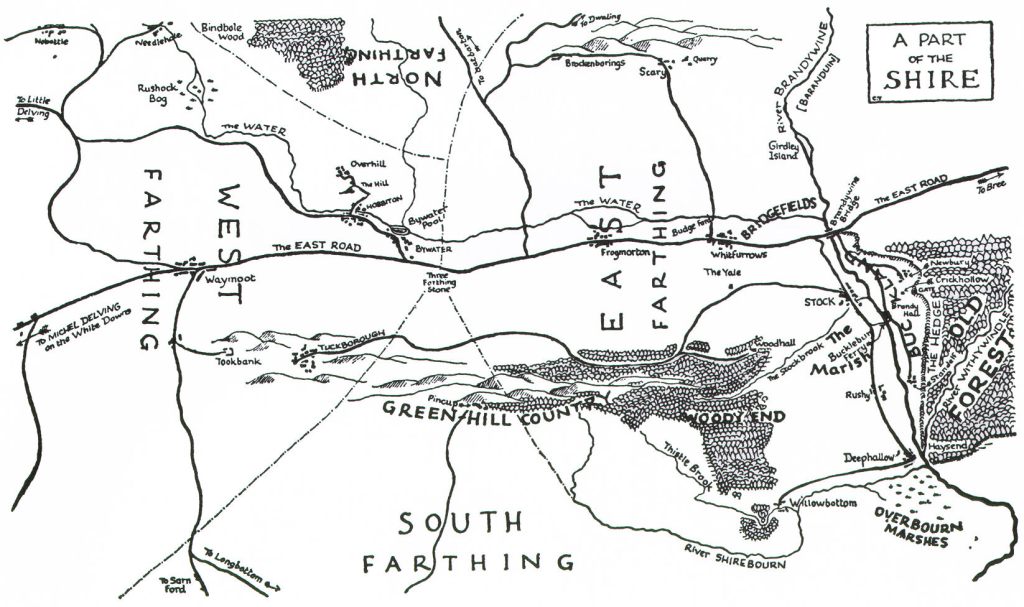

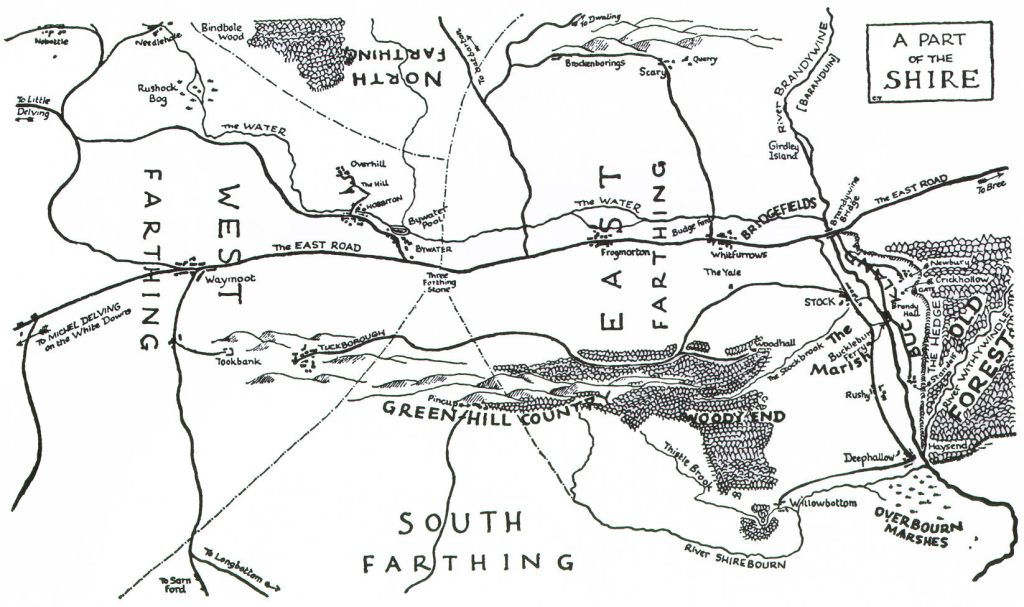

(Christopher Tolkien)

crossing the Greenway ( the old north/south road—more about this in a moment) at Bree and proceeding eastwards from there–

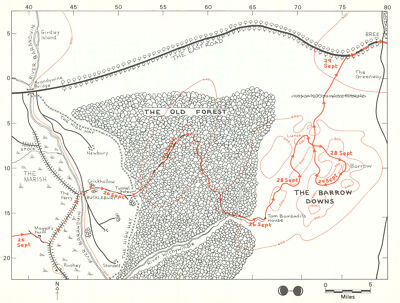

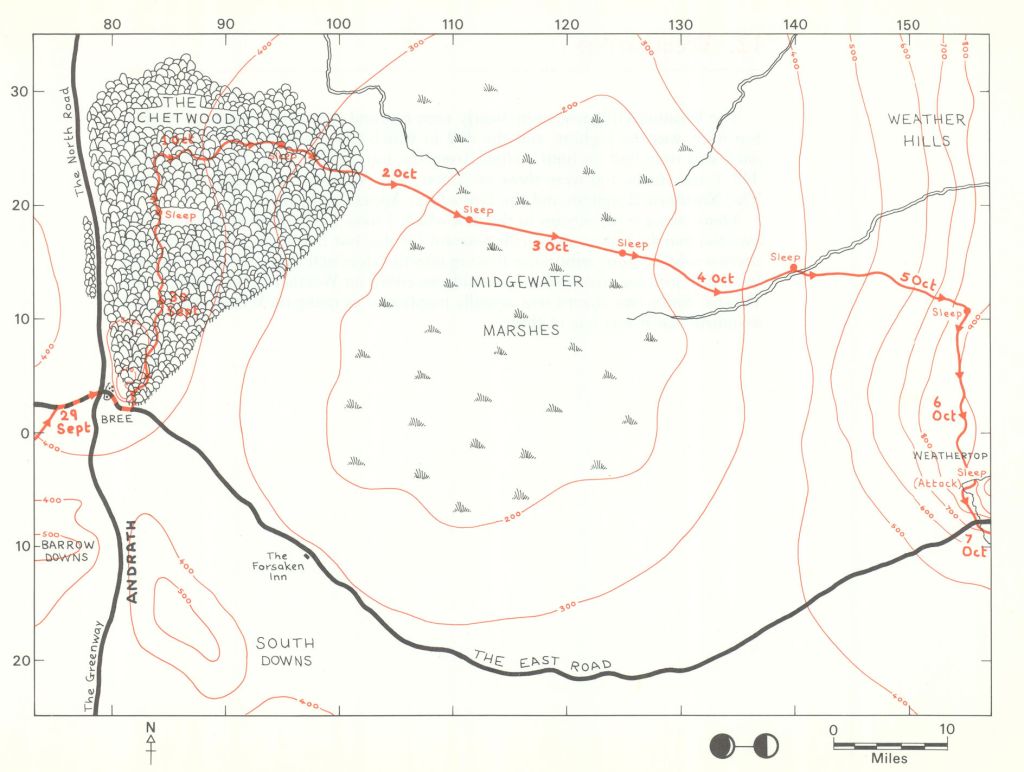

(Barbara Strachey, The Journeys of Frodo, 1981)

although Frodo and his friends, led by Strider,

(the Hildebrandts)

took an alternate route from there to Weathertop.

Because I’m always interested in the physical world of Middle-earth, I try to imagine what, in our Middle-earth, either suggested things to JRRT, or at least what we can use to try to reconstruct something comparable.

For the Great East Road, because it was constructed by the kings of Arnor, and had a major bridge (the Bridge of Strongbows—that is, strong arches), across the Brandywine,

(actually a 16thcentury Ottoman bridge near the village of Balgarene in Bulgaria. For more on Bulgarian bridges, some of which are quite spectacular, see: https://vagabond.bg/bulgarias-wondrous-bridges-3120 )

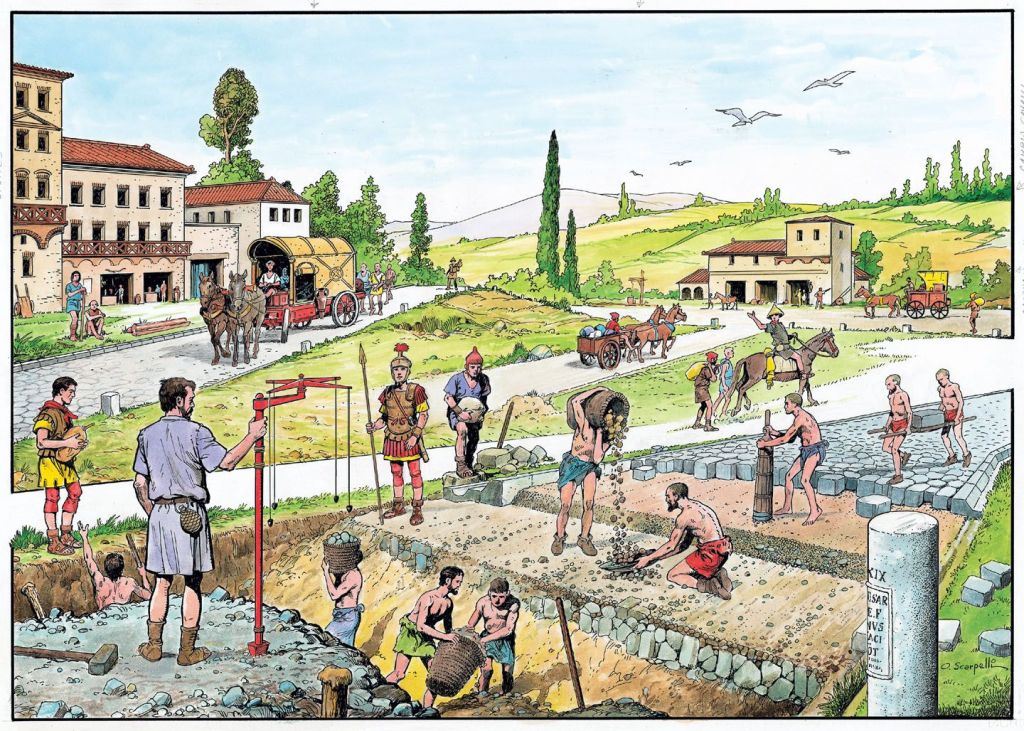

I had imagined something like a Roman road, wide, paved, with perhaps drainage on both sides.

The Romans were serious engineers and roads could be very methodically laid out and built.

Latest research suggests that they may have constructed as many as almost 200,000 miles of roads (299,171km)—not all so elaborate, and some were doubtless improved local roads, but a vast number (see for more: https://www.sciencealert.com/massive-new-map-reveals-300000-km-of-ancient-roman-roads ) were of the standard construction.

This may have been true once, but the road Frodo and his friends eventually reach doesn’t sound much like surviving Roman work—

“…the Road, now dim as evening drew on, wound away below them. At this point it ran nearly from South-west to North-east, and on their right it fell quickly down into a wide hollow. It was rutted and bore many signs of the recent heavy rain; there were pools and pot-holes full of water.” (The Fellowship of the Ring, Book One, Chapter 8, “Fog on the Barrow-downs”)

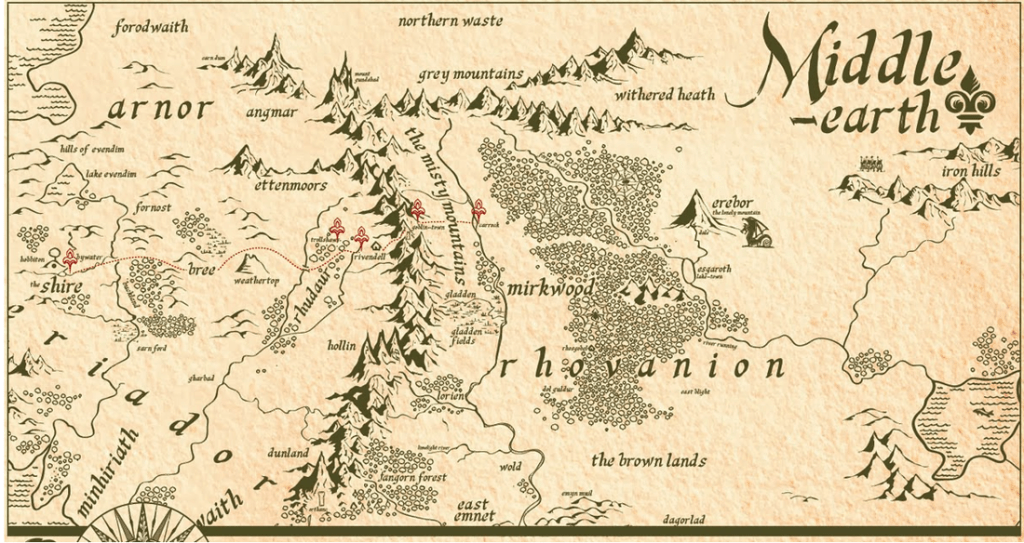

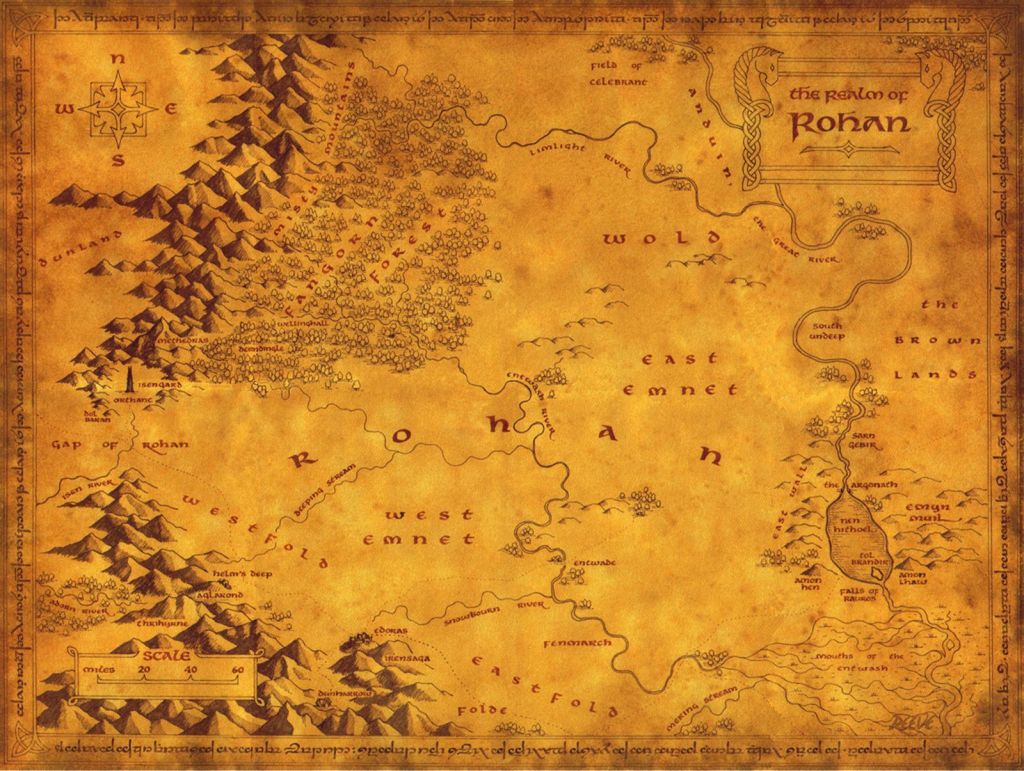

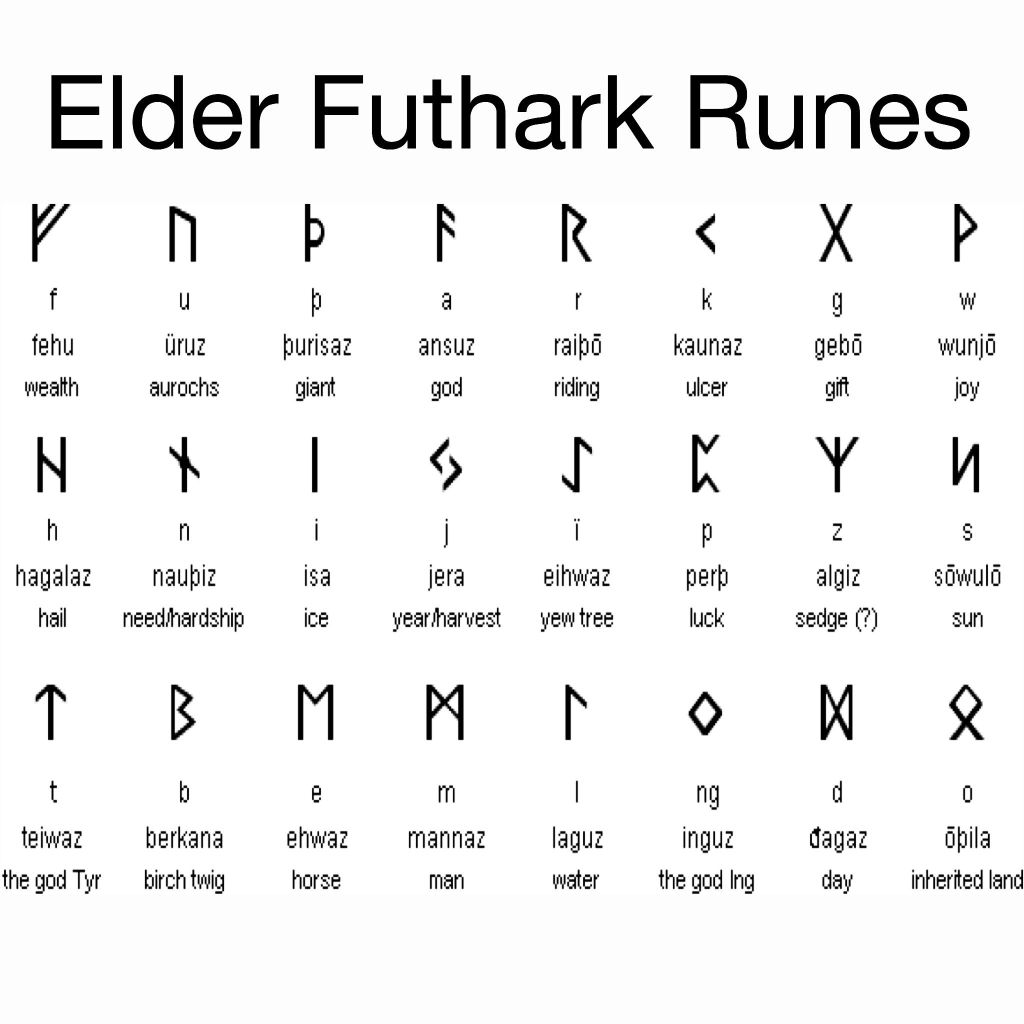

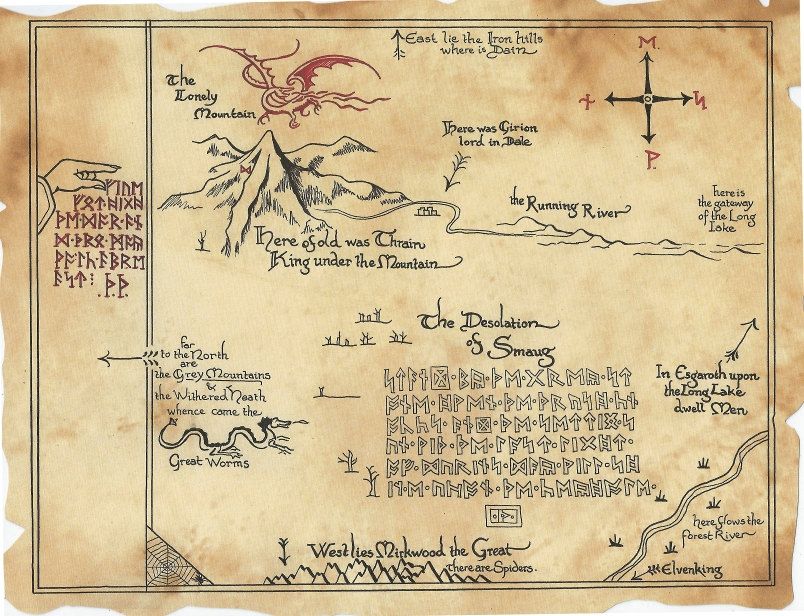

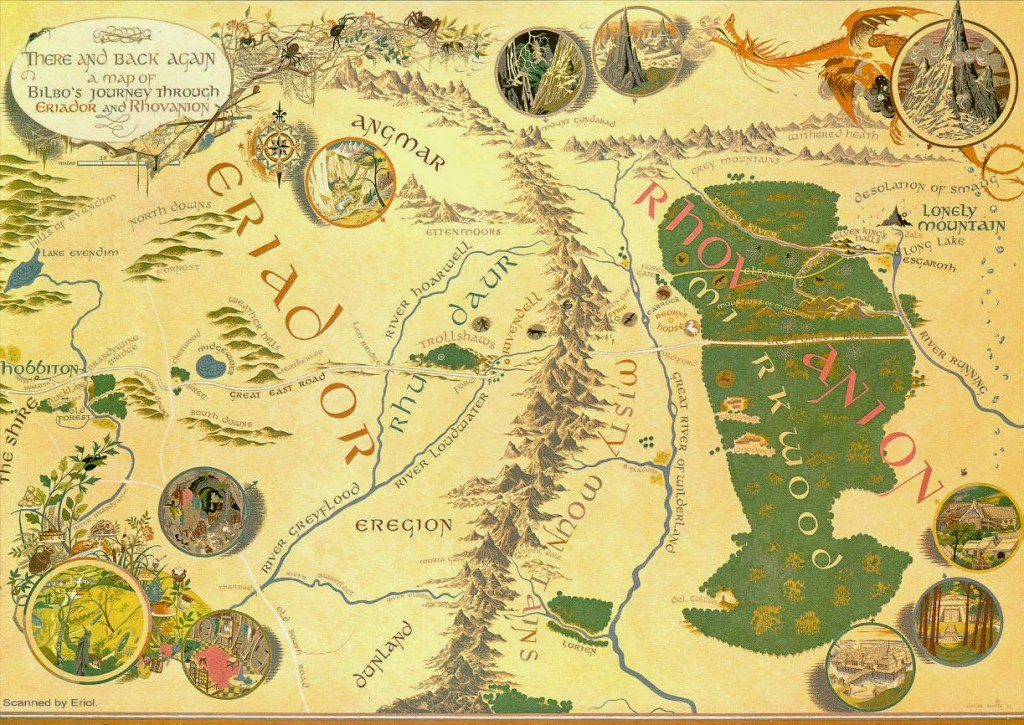

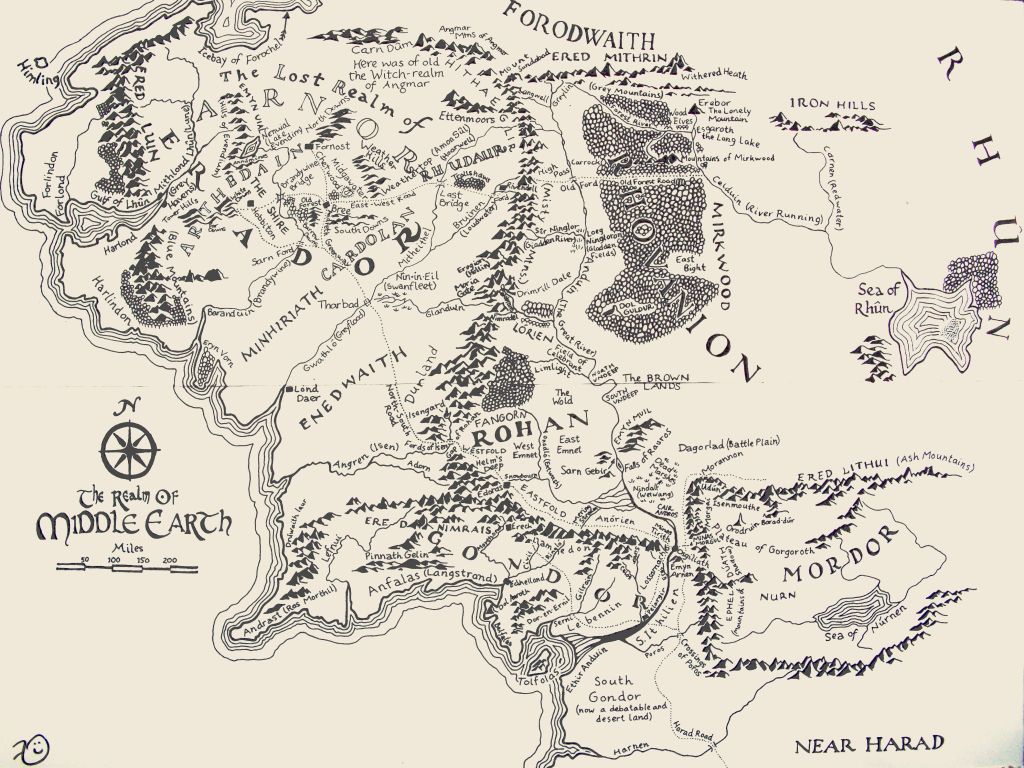

Following the road, however, has made me consider just how many miles of roads we actually see in Middle-earth and over which various characters travel and how they might appear. Just look at a map—

(cartographer? clearly based on JRRT and Christopher Tolkien’s map)

The Great East Road (named “East-West Road” there) is drawn and identified, and we can see the North Road (as “North-South Road”), but these are hardly the only roads in Middle-earth and certainly not in the story, and, as we’re following Frodo & Co. on their journeys, I thought that it would be interesting to examine some of the others—the main ones, and one nearly-lost one.

So, when Frodo and his friends eventually reach the edge of Bree, they’re actually at a crossroads—

“For Bree stood at the old meeting of ways: another ancient road crossed the East Road just outside the dike at the western end of the village, and in former days Men and other folk of various sorts had traveled much on it. ‘Strange as News from Bree’ was still a saying in the Eastfarthing, descending from those days, when news from North, South, and East could be heard in the inn, and when the Shire-hobbits used to go more to hear it.”

With the fall of the northern realm of Arnor about TA1974, however, things had changed:

“But the Northern Lands had long been desolate, and the North Road was now seldom used: it was grass-grown, and the Bree-folk called it the Greenway.” (The Fellowship of the Ring, Book One, Chapter 9, “At the Sign of the Prancing Pony”)

We’re not given a detailed description of this road—was it like what I had imagined the Great East Road might have looked like, Roman and paved, but overgown?

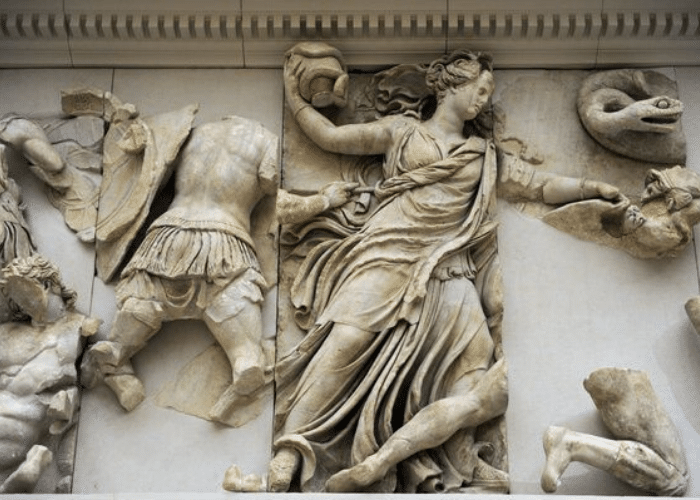

If so, it led back to the city of Tharbad to the south, which had had its own elaborate bridge at the River Greyflood—

“…where the old North Road crossed the river by a ruined town.”

Of this bridge we know:

“…both kingdoms [Arnor and Gondor] together built and maintained the Bridge of Tharbad and the long causeways that carried the road to it on either of the Gwathlo [Greyflood]…” (JRRT Unfinished Tales, 277)

It must have been massive—could it have looked something like this?

(the 1ST century Roman bridge at Merida, Spain—you can read about it here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Puente_Romano,_M%C3%A9rida )

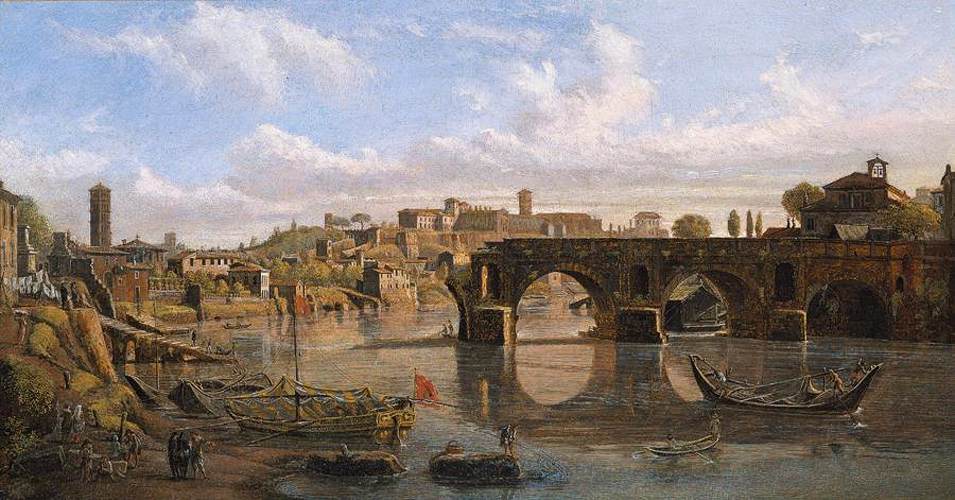

As we also know, it had fallen into ruin, becoming only a dangerous ford, as Boromir found out, losing his horse there on the way north (The Fellowship of the Ring, Book Two, Chapter 8, “Farewell to Lorien”)

(the “Ponte Rotto” (“ruined bridge”) actually the 2nd century BC Pons Aemilius. You can read about it here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pons_Aemilius This is a 1690 painting by Caspar van Wittel, a very interesting and talented man, and you can read about him here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Caspar_van_Wittel )

We’ll pause here, however, waiting, perhaps, for a drought,

before we continue down the road towards Gondor…

Thanks for reading, as always.

Stay well,

Don’t cross any bridge till you come to it,

And remember that there’s always

MTCIDC

O