Tags

'Salem's Lot, Acrophobia, Arachnophobia, Billina, Claustrophobia, Coulrophobia, Dracula, ECT, Film, Goblins, Gump, Herpetophobia, jack-pumpkinhead, nome-king, Oz, Ozma of Oz, Return to Oz, Smaug, spiders, Stephen King, The Hobbit, The Marvelous Land of Oz, The Shining, Tik-Tok, Tolkien, trolls, Trypanophobia, Wheelers, wolves

Welcome, dear readers, as always.

Does this picture make your hands sweat? Can you barely look at it?

How about this one—

Or this one—

Or—

Or—

Or—horror of horrors!—

It’s possible that all of these might have an effect upon you and, in which case, I imagine that you’re reading this hiding under your bed.

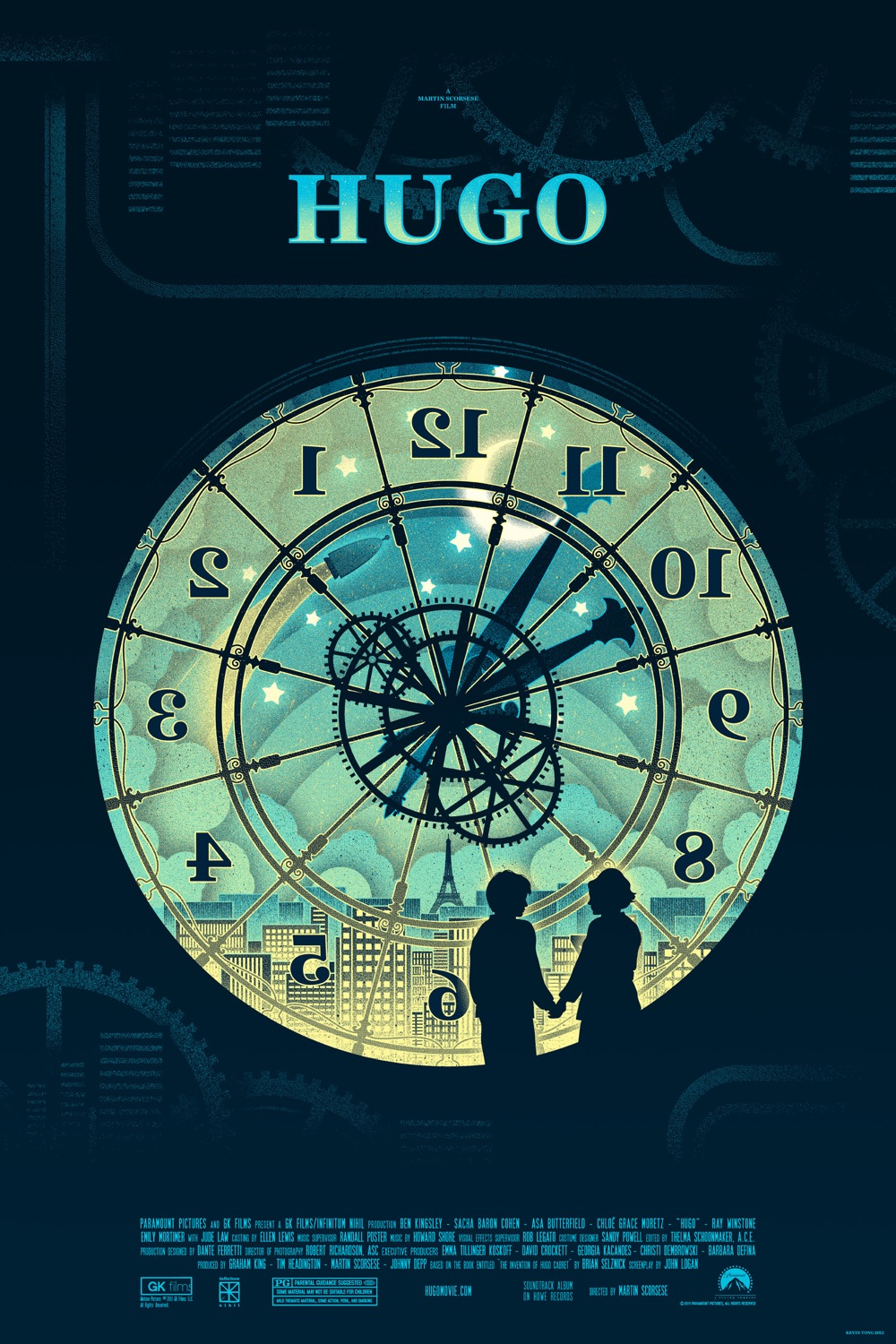

Why all of this phobic display? Because, back in June, I read an article from the BBC about the 40th anniversary of Disney’s Return to Oz entitled:

“ ‘It has the appeal of an actual horror’: How Return to Oz became one of the darkest children’s films ever made”

(You can read the article here: https://www.bbc.com/culture/article/20250616-the-darkest-childrens-film-ever-made )

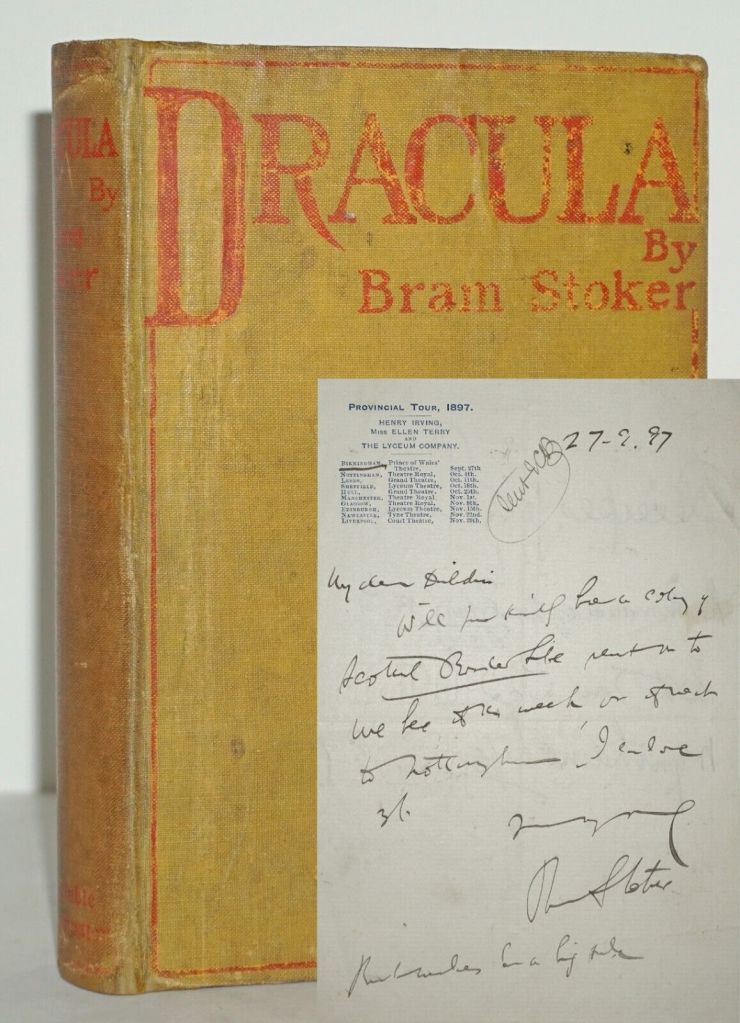

This is a film I own and have seen perhaps half-a-dozen times and I’ve never viewed it as the horror film which the article would suggest. Granted, sensationalism sells the news, but, having read the article again, I’ve thought about how horror can be an element in a work—and a powerful one—without making the work as a whole into something like Bram Stoker’s Dracula.

(And, if you haven’t read it, I would certainly recommend it. Here it is in the first US edition of 1897: https://gutenberg.org/files/345/345-h/345-h.htm )

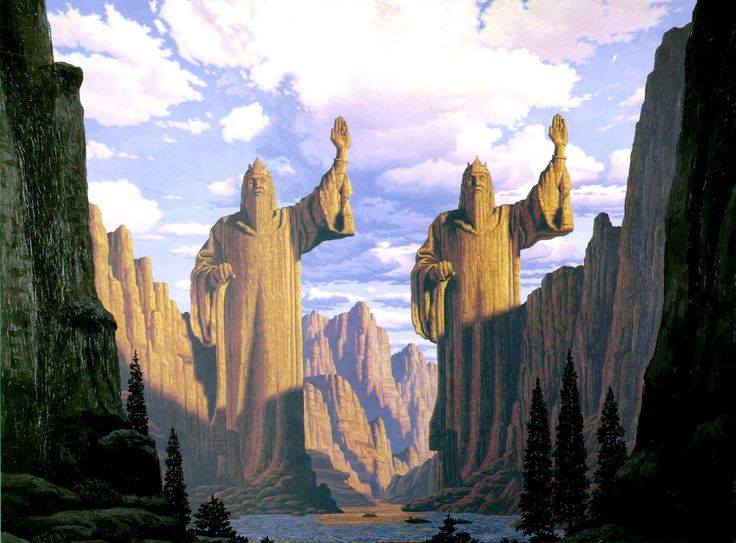

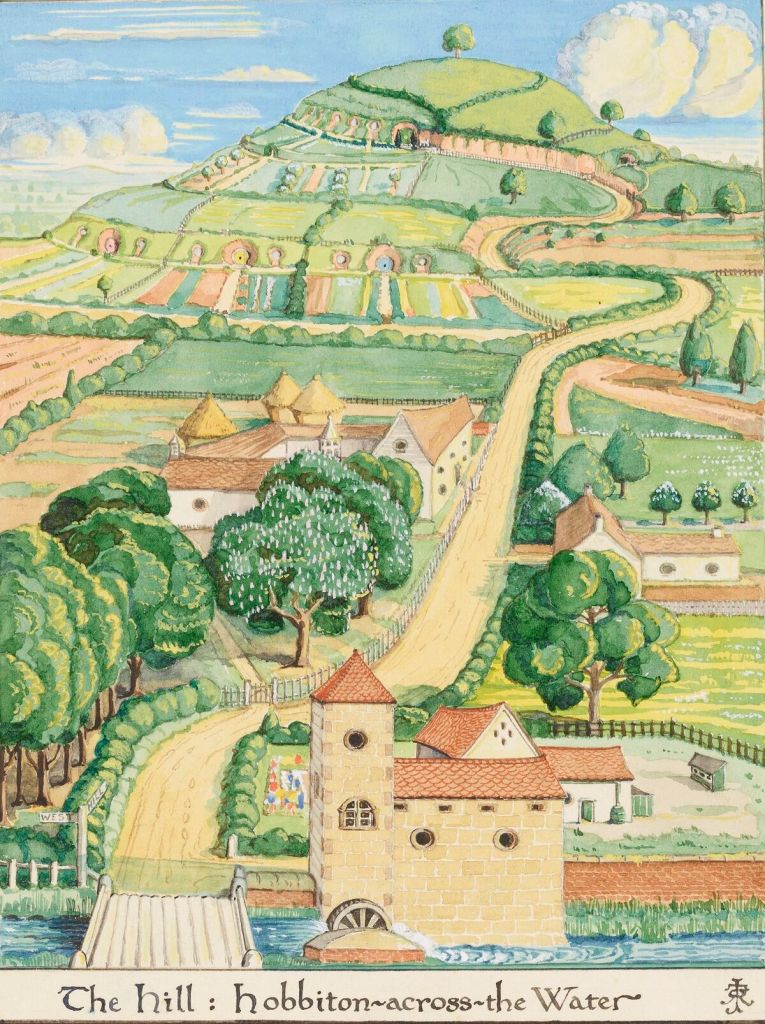

Think, for a moment, about The Hobbit.

Here, we go from the safety of Hobbiton

(JRRT)

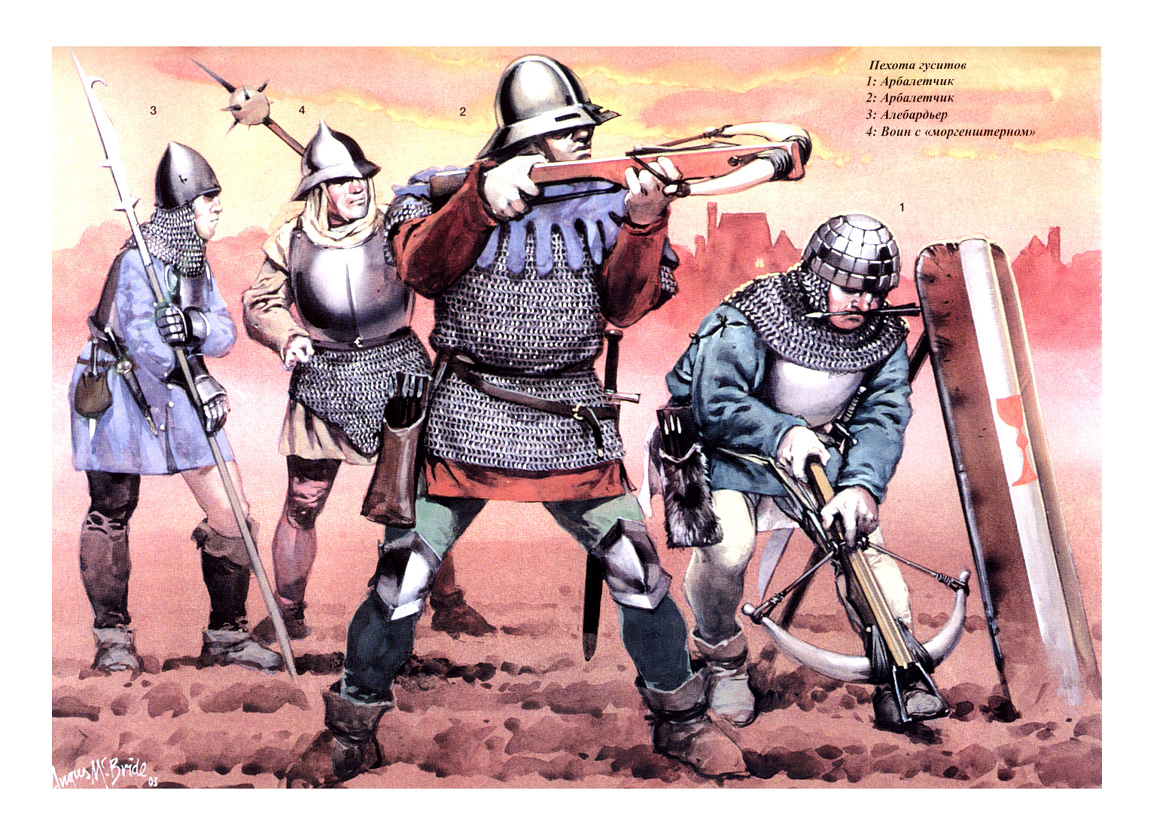

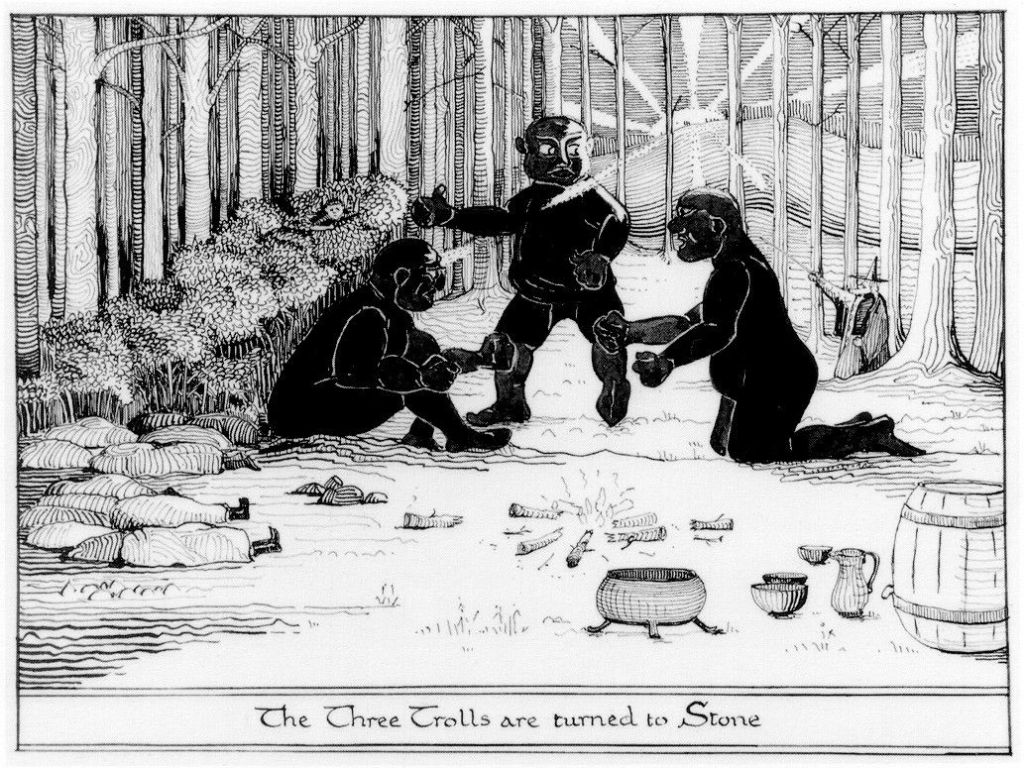

to a world where there are trolls,

(JRRT)

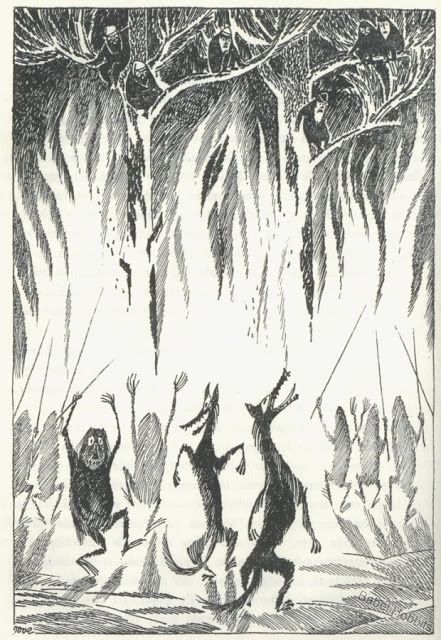

goblin-infested mountains,

(Alan Lee)

wolves in large packs,

(Tove Jansson)

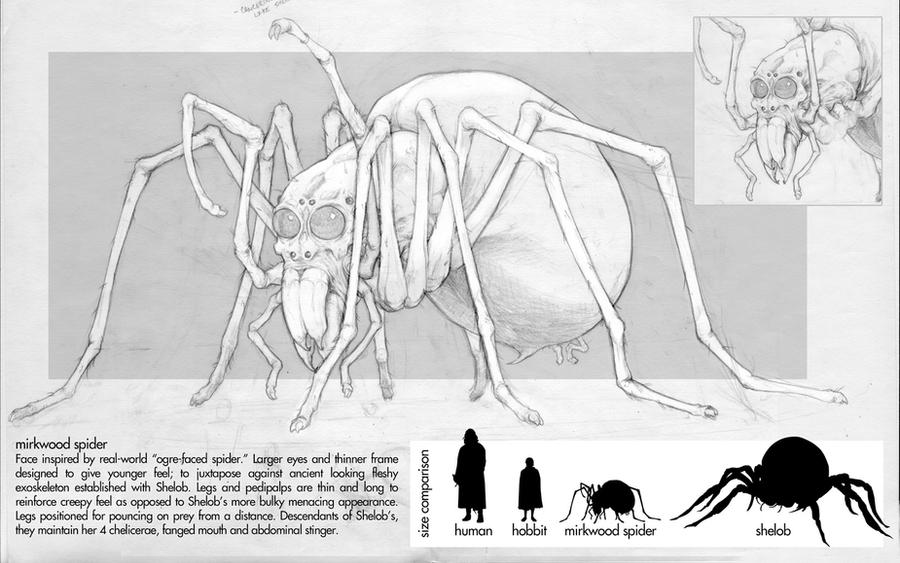

giant spiders,

(John Tyler Christopher—you can see more of his work here: https://johntylerchristopher.com/ )

and, finally, an intelligent and vengeful dragon.

(JRRT)

But does the appearance of all these dangers make the book a horror novel, like one of Stephen King’s more forbidding works?

The article points to some potentially disturbing moments—and at least the first is certainly disturbing and, interestingly, is not in the two books upon which the film is based—The Marvelous Land of Oz, 1904,

and Ozma of Oz, 1907. (For more on the combination and the scriptwriters’ changes, see: “Chickening In”, 12 February, 2025)

The Kansas of the 1939 film was as bleak as a 1930s sound stage could make it, in sepia, suggesting photos of the Dust Bowl of the Great Depression era—

The 1985 movie showed us the real rolling hills of Kansas and the ruin of Uncle Henry and Aunt Em’s farm.

(This is at the end of the film, when the house has been rebuilt—early in the film, the house—which, of course, was ripped from Kansas and dropped on the Wicked Witch of the East—remains unfinished and Uncle Henry crippled from the twister.)

Dorothy, to Aunt Em, also seems somehow ruined, having reappeared after the tornado with stories about having been in a foreign land, Oz, but with no proof of it, and Em, having seen a newspaper ad for medical treatment by electricity, decides to take Dorothy to the clinic and its all-too-calm and rational Dr. Worley.

The treatment consists of running a powerful electrical current through Dorothy’s brain, (now called ECT—electroconvulsive therapy), which is supposed to erase Dorothy’s (supposedly false) memory of Oz.

As the audience, with its own memories of Oz, from the 1939 film, the many books, or both, knows perfectly well that Oz is real, as is Dorothy’s memory of it, and, as the article points out:

“…the power of these scenes lies in the fact that they are trying to silence Dorothy, to obliterate her memories of Oz”

Dorothy escapes the clinic (one might really says “asylum”, as it has that grim look of Victorian asylums for the insane)

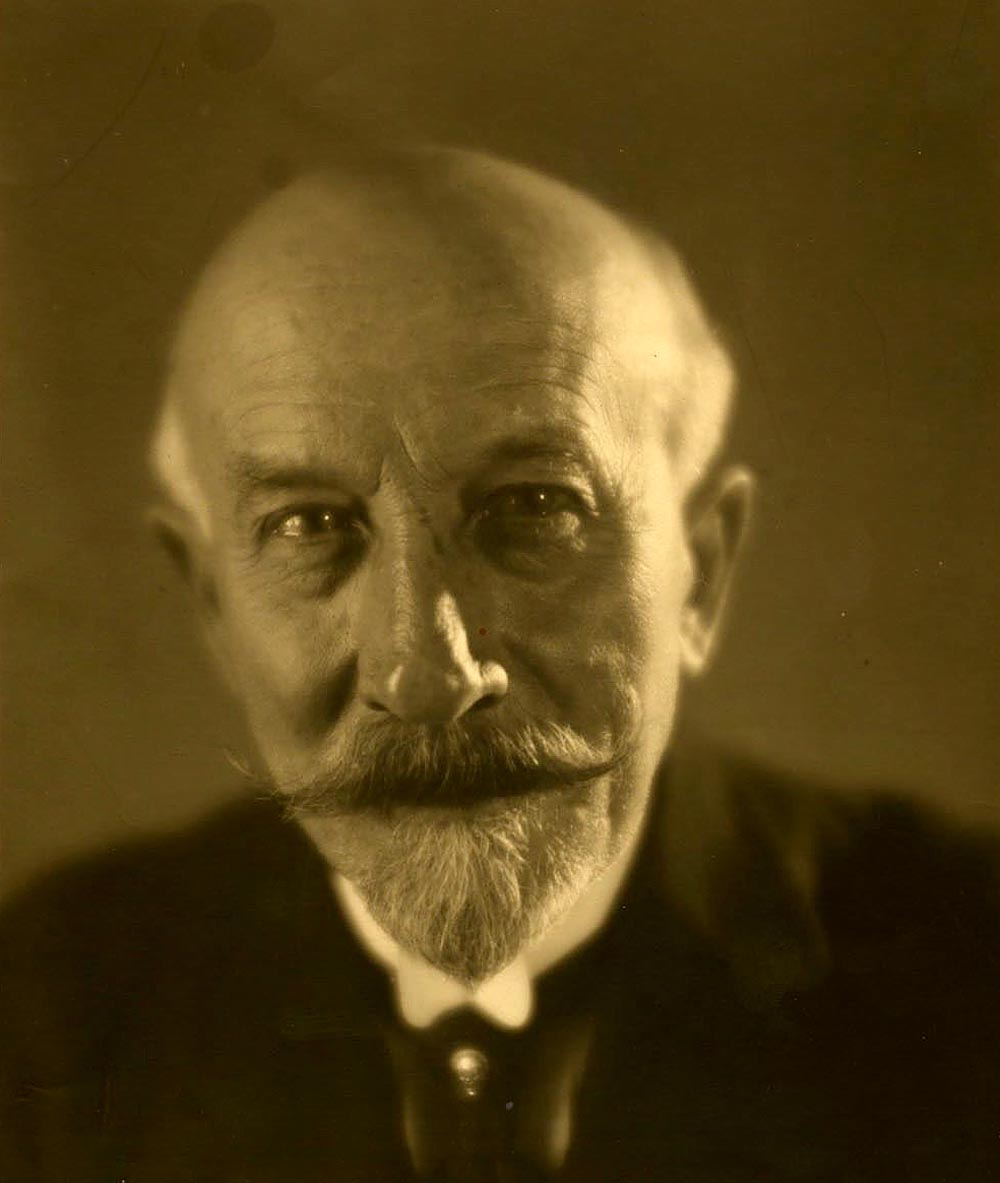

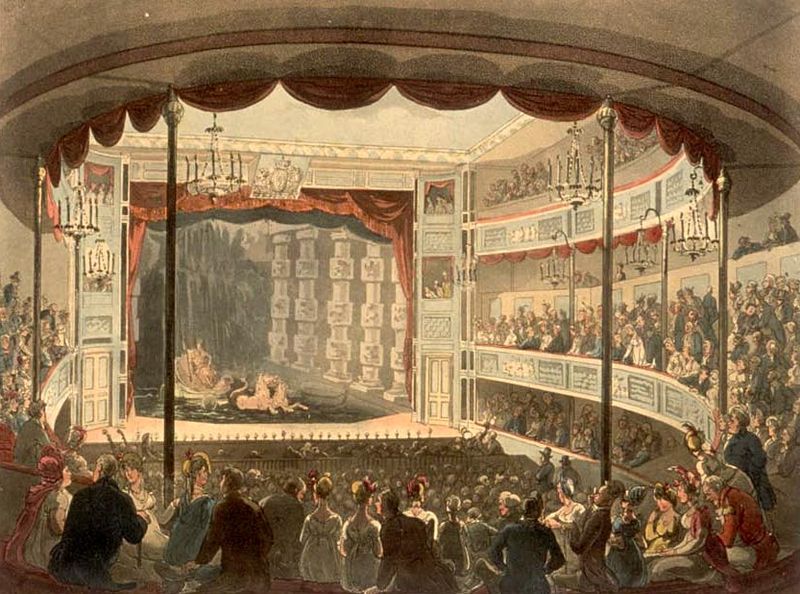

(A real Victorian asylum—and not the grimmest, there being some real competition here)

and turns up in Oz, once more, where the article mentions other potentially disturbing elements:

the destruction of Oz and its citizens petrified,

its ruins haunted by the Wheelers,

the minions of Princess Mombi, who collects heads and wears them for different occasions,

and then there is the Nome King, who is the current ruler of Oz,

and is the destroyer of the Emerald City, the overlord of Mombi, and has enchanted Dorothy’s former friends, the Scarecrow, the Tinman, and the Cowardly Lion, turning them into inanimate objects.

For the sake of sensationalism, it seems that the article leans heavily on these—as if, I suggested above, one could do the same for The Hobbit, but this leaves out the fact that, although Dorothy’s first allies in Oz have been neutralized, she finds others, just as Bilbo has dwarves, Gandalf, Elrond, the Eagles, and Beorn, not to mention Sting and the Ring.

These include the caustic hen, Billina, who arrives with her from Kansas,

“the Army of Oz”—Tik-Tok,

Jack Pumpkinhead,

and the Gump.

I teach story-telling on a regular basis and a dictum I use is “No fiction without friction” . Just as trolls, goblins, wolves, Gollum, spiders, and Smaug provide the friction in The Hobbit, so the clinic and its smooth-talking doctor, the Wheelers, Princess Mombi, and the Nome King, provide it in Return to Oz. These plot elements supply the problems which must be solved before the ultimate goal of the story can be achieved—coming home safely (and much better-off) for Bilbo, coming home and keeping her memories of Oz for Dorothy (guaranteed for her when she sees Ozma, rescued from the Nome King, in her mirror in Kansas).

Disturbing moments—in both—what’s that riddle contest with Gollum if nothing short of harrowing?—but is Return to Oz just this side of a horror movie? As always, I suggest that you see it for yourself, but remember “no fiction without friction” before you rank it with The Shining.

Thanks, as ever, for reading.

Stay well,

Pick a bed with a reasonable clearance,

And remember that, as always, there’s

MTCIDC

O