Tags

Beowufl, Beowulf, Dragons, Fantasy, Smaug, The Blitz, The Great War, The Hobbit, The Lonely Mountain, The Reluctant Dragon, Tolkien

Welcome, as always, dear readers.

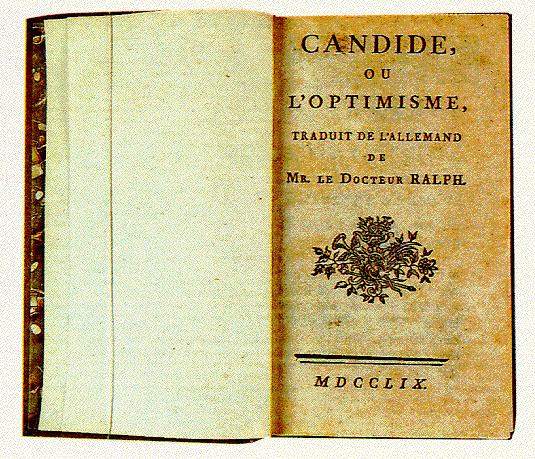

I’m always interested in influences on Tolkien and have written about them here and there in the past. It’s clear that he was always susceptible to them and would sometimes, when questioned, candidly admit to them, as he did, in this letter to the editor of The Observer:

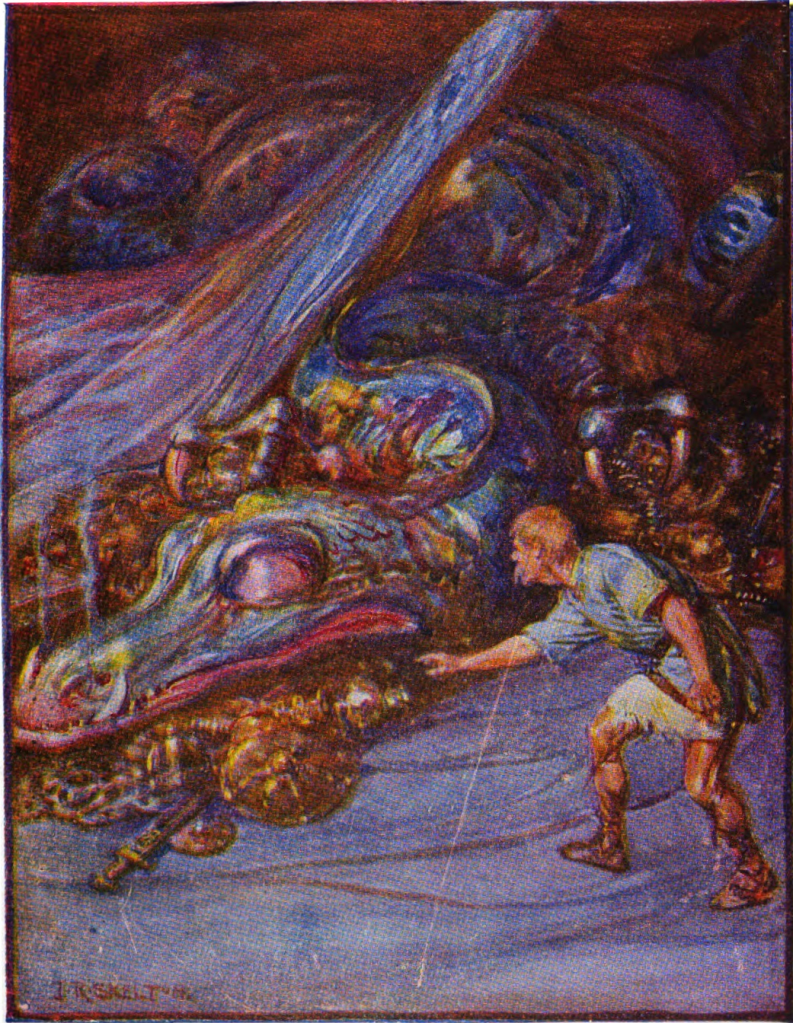

“Beowulf is among my most valued sources; though it was not consciously present to the mind in the process of writing, in which the episode of the theft [of a cup by an escaped slave from a dragon’s hoard] arose naturally (and almost inevitably) from the circumstances. It is difficult to think of any other way of conducting the story at that point. I fancy the author of Beowulf would say much the same.” (letter to the editor of The Observer, printed 20 February, 1938, Letters, 41)

This theft and its consequences are readily apparent in Beowulf. Athough, unlike Smaug, he never speaks a word, the dragon who has suffered the loss very eloquently protests that theft—

”Then the baleful fiend its fire belched out,

and bright homes burned. The blaze stood high

all landsfolk frighting. No living thing

2315would that loathly one leave as aloft it flew.

Wide was the dragon’s warring seen,

its fiendish fury far and near,

as the grim destroyer those Geatish people

hated and hounded. To hidden lair,

2320to its hoard it hastened at hint of dawn.

Folk of the land it had lapped in flame,

with bale and brand.”

(from Francis Gummere’s 1909 translation, which you can read here: https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/The_Oldest_English_Epic This is an old, but still very handy, volume, as it contains not only Beowulf, but a number of other Old English poems, and includes, as well, the Germanic Hildebrandslied. The latter is one of the puzzles of early Germanic literature and there’s a very useful article about it here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hildebrandslied#Sources If you’d like to see where Tolkien might have first learned the story as a child, see: https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/The_red_book_of_animal_stories/The_Story_of_Beowulf_and_the_Fire_Drake which is from the 1899 The Red Book of Animal Stories which you can read here: https://archive.org/details/redbookanimalst00fordgoog/page/n11/mode/2up )

Along with the theft, Tolkien actually uses the idea of dragon destruction more than once, beginning with:

“The pines were roaring on the height,

The winds were moaning in the night.

The fire was red, it flaming spread;

The trees like torches blazed with light.

The bells were ringing in the dale

And men looked up with faces pale;

The dragon’s ire more fierce than fire

Laid low their towers and houses frail.”

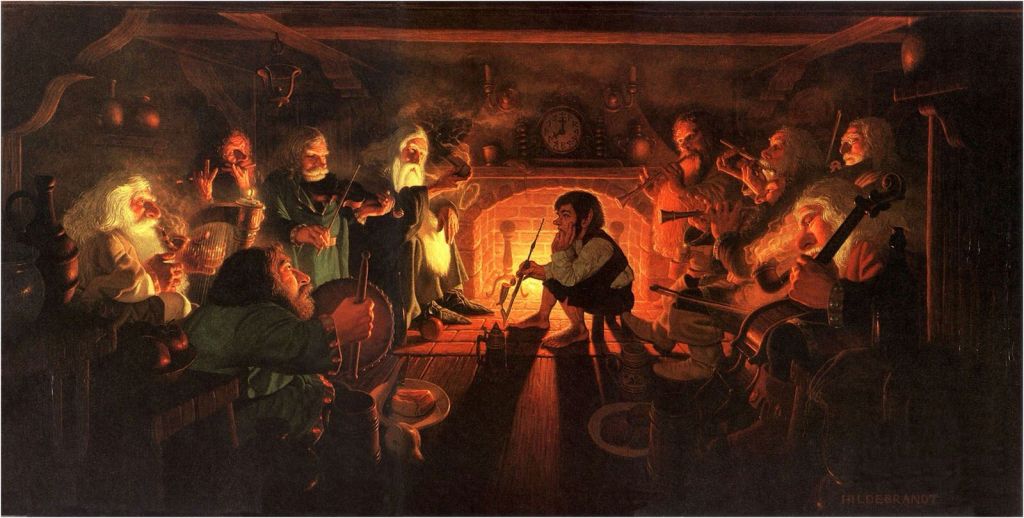

(The Hobbit, Chapter One, “An Unexpected Party”)

where the dwarves sing it in the dark in Bilbo’s house.

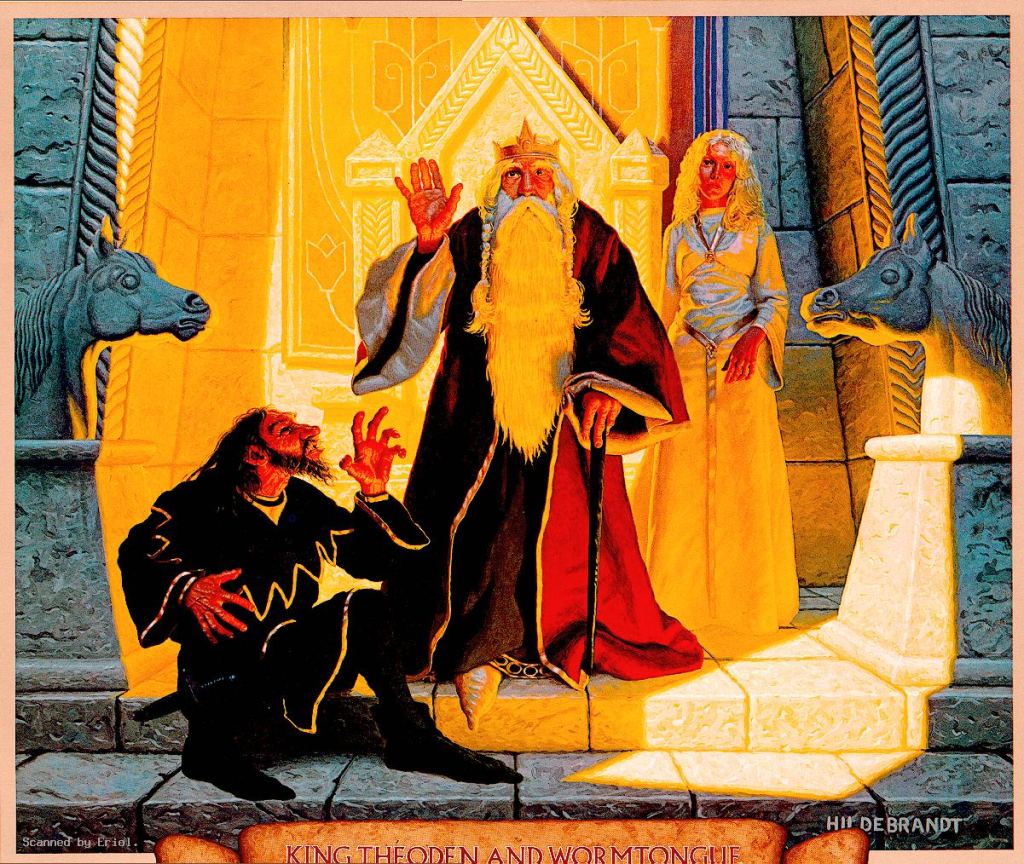

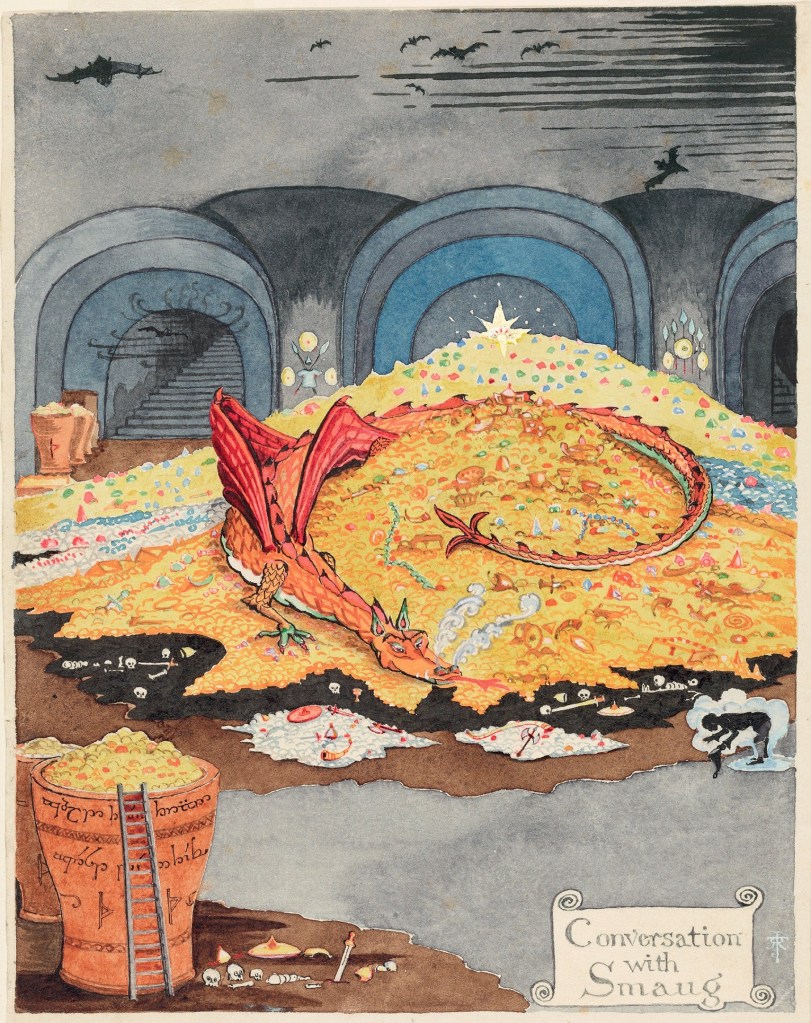

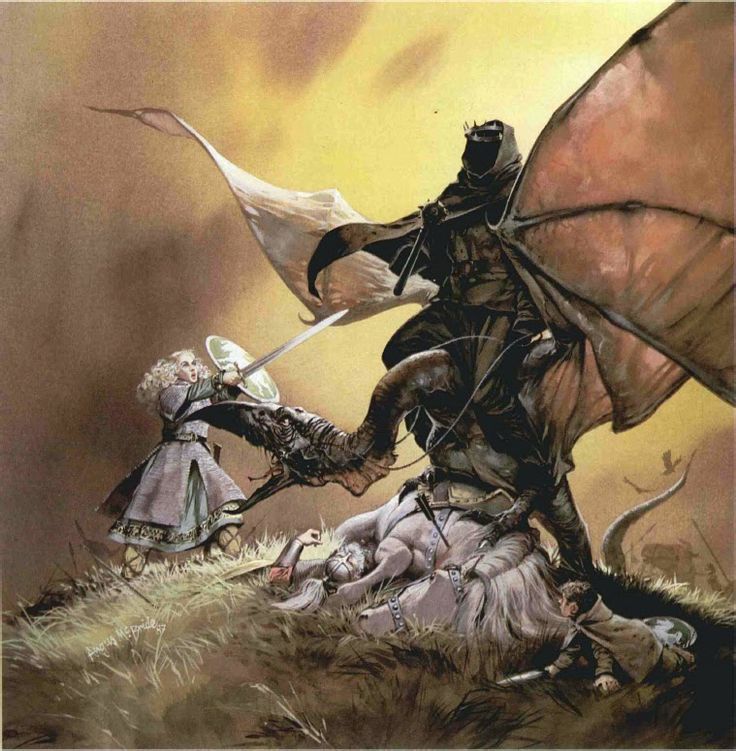

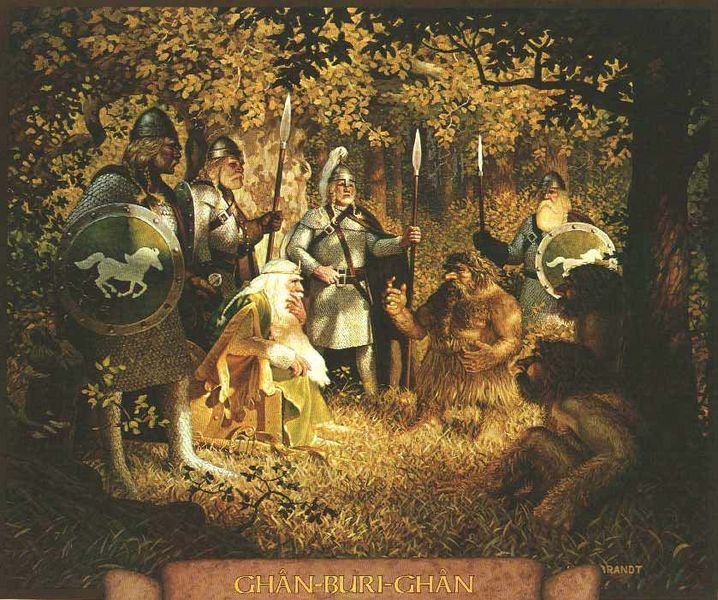

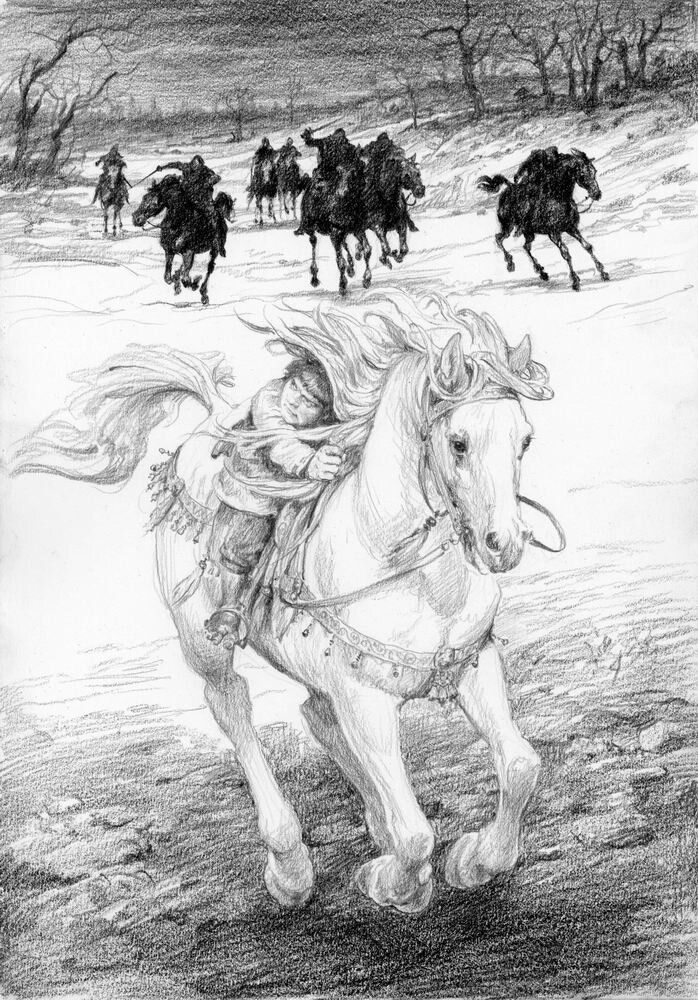

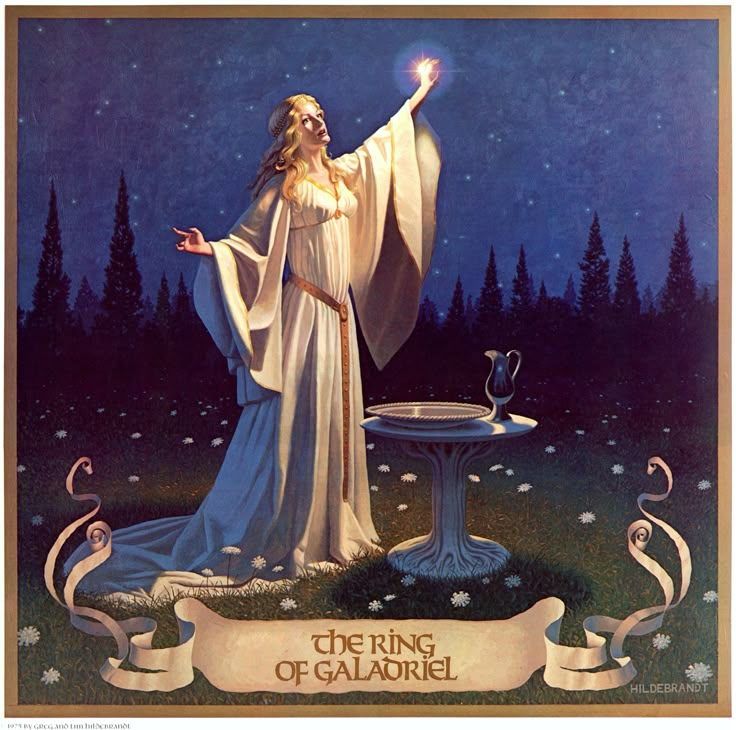

(the Hildebrandts)

This is a poetic description of Smaug’s initial taking possession of Mt Erebor (“the Lonely Mountain”), after destroying the town of Dale, just below it.

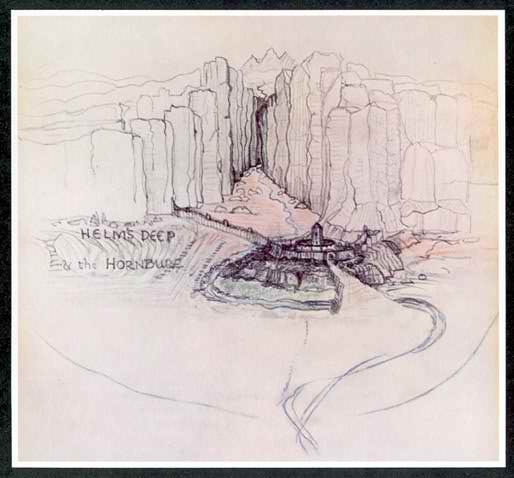

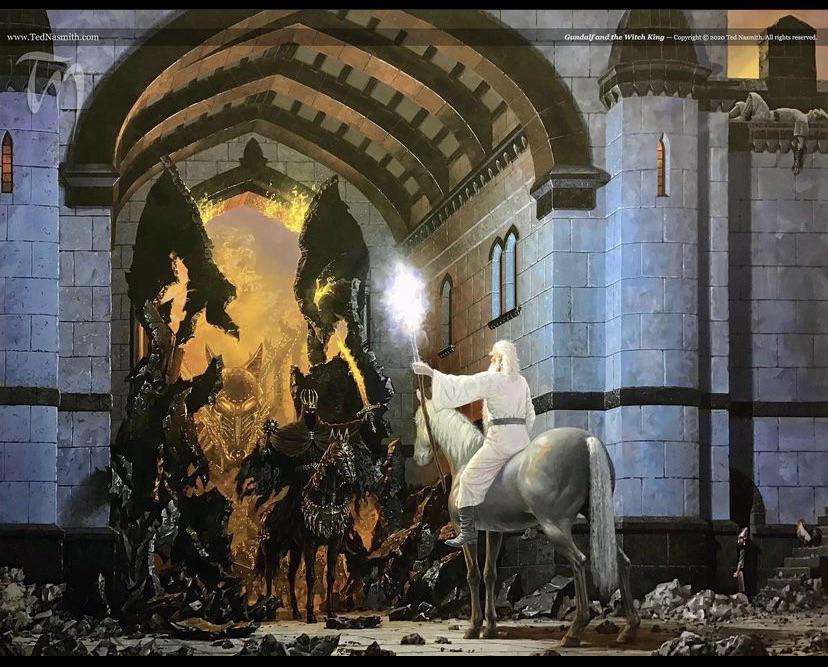

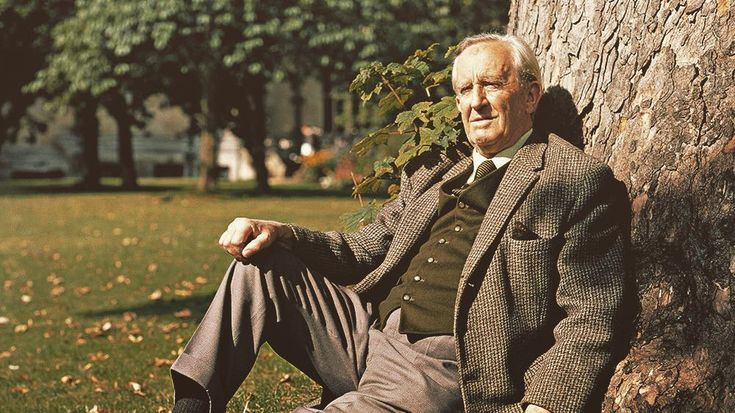

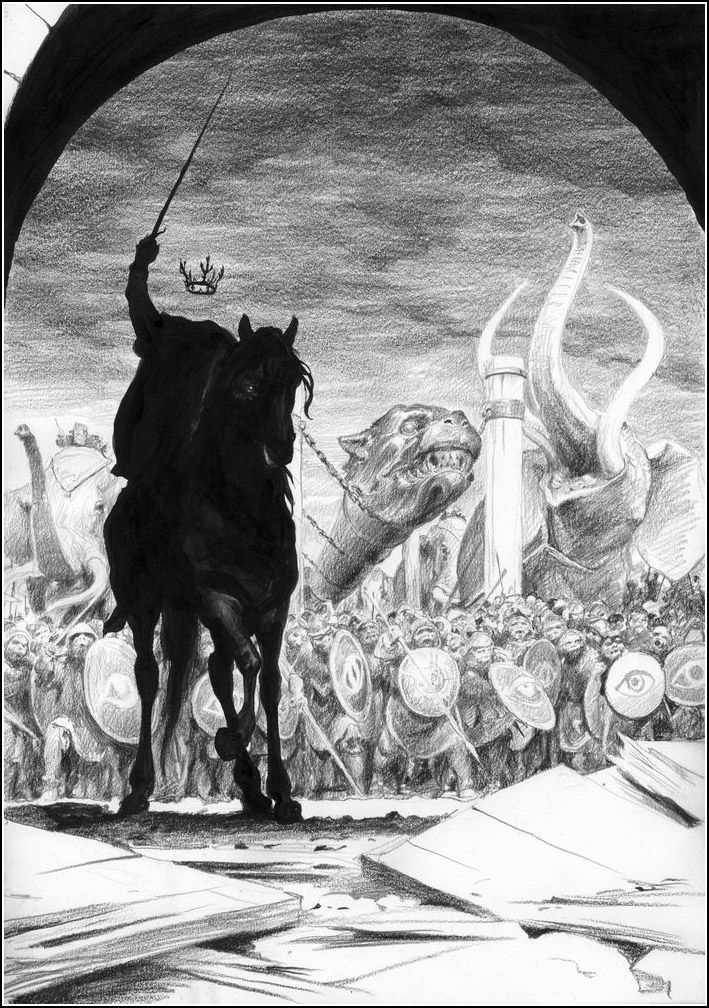

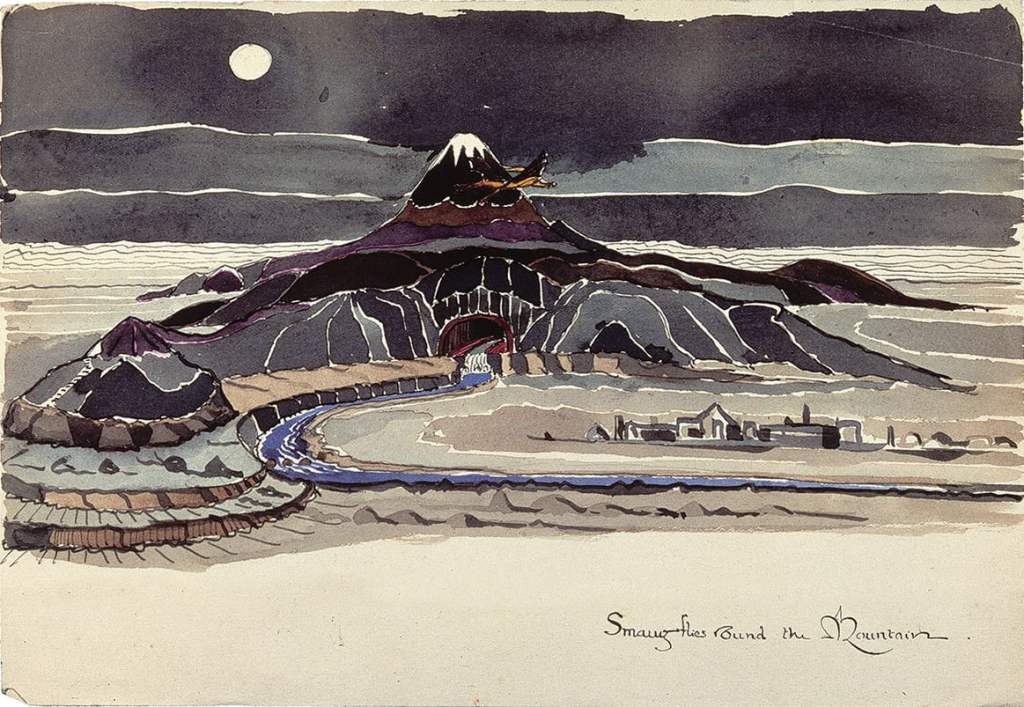

(JRRT You can see the remains of Dale, just to the lower right.)

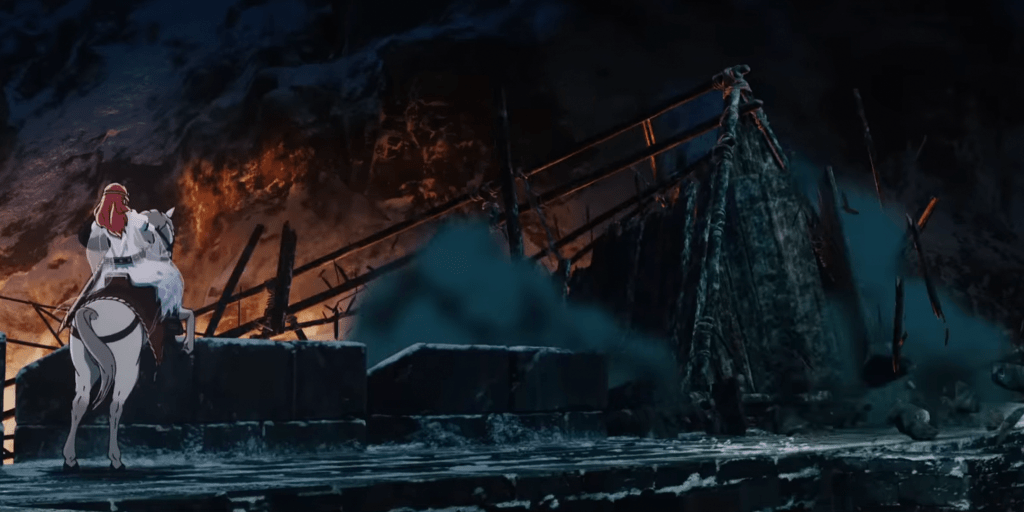

We’ll see more of this when Smaug later attacks Lake-town—

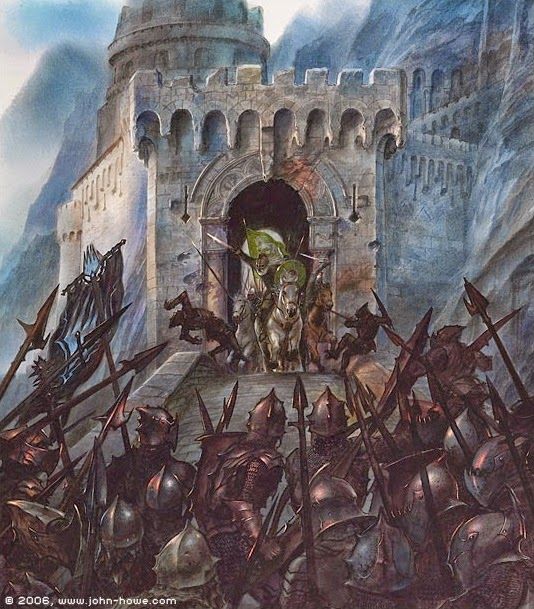

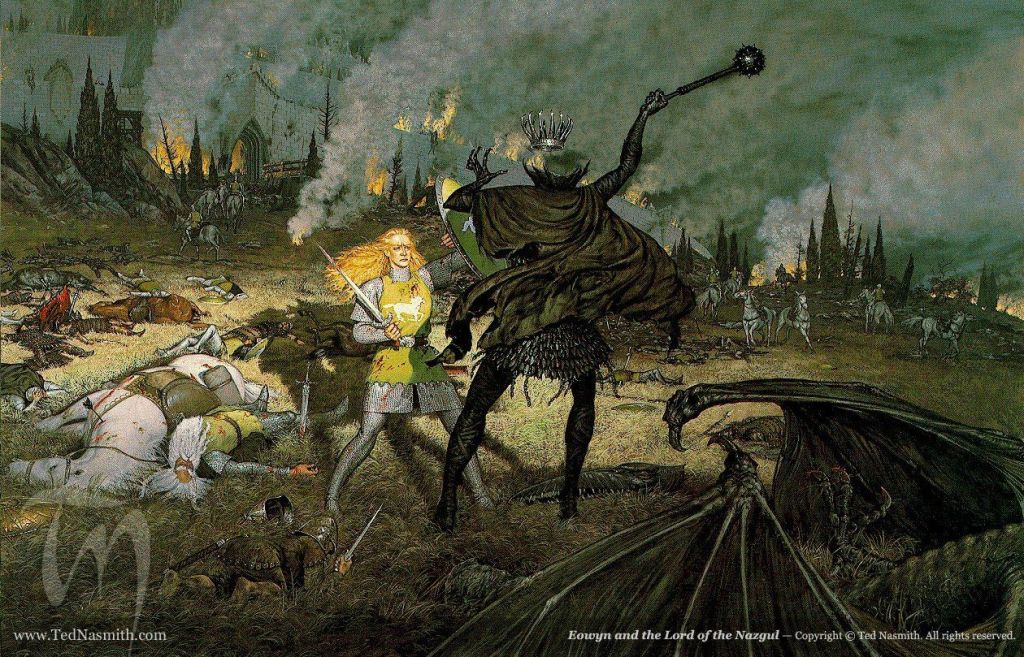

(Christopher Burdett—you can see more of his work at: https://christopherburdett.blogspot.com/2012/08/lotr-battle-of-lake-town.html For Burdett’s grand and wonderfully imaginative project, “The Grand Bazaar of Ethra VanDalia”, see: https://christopherburdett.com/work/grandbazaar )

“Fire leaped from thatched roofs and wooden beam-ends as he [Smaug] hurtled down and past and round again…Back swirled the dragon. A sweep of his tail and the roof of the Great House crumbled and smashed down. Flames unquenchable sprang high into the night. Another swoop and another, and another house and then another sprang afire and fell…” (The Hobbit, Chapter Fourteen, “Fire and Water”)

This is wonderful, vivid story-telling, but, for me, the most powerful part of it is not the destruction itself, but the consequences of such destruction, beginning with Smaug’s original arrival, something which Bilbo only learns about from eavesdropping on the boatmen, in whose barrels Bilbo has hidden the dwarves in their escape from the forest elves.

(JRRT)

“As he listened to the talk of the raftmen and pieced together the scraps of information they let fall, he soon realized that he was very fortunate ever to have seen it [the Lonely Mountain] at all, even from this distance…The talk was all of the trade that came and went on the waterways and the growth of the traffic on the river, as the roads out of the East towards Mirkwood vanished or fell into disuse; and of the bickering of the Lake-men and the Wood-elves about the upkeep of the Forest River and the care of the banks. Those lands had changed much since the days when dwarves dwelt in the Mountain…Great floods and rains had swollen the waters that flowed east; and there had been an earthquake or two (which some were inclined to attribute to the dragon…). The marshes and bogs had spread wider and wider on either side. Paths had vanished, and many a rider and wanderer too, if they had tried to find the lost ways across. The elf-road through the wood which the dwarves had followed on the advice of Beorn now came to a doubtful and little used end at the eastern edge of the forest…” (The Hobbit, Chapter Ten, “A Warm Welcome”)

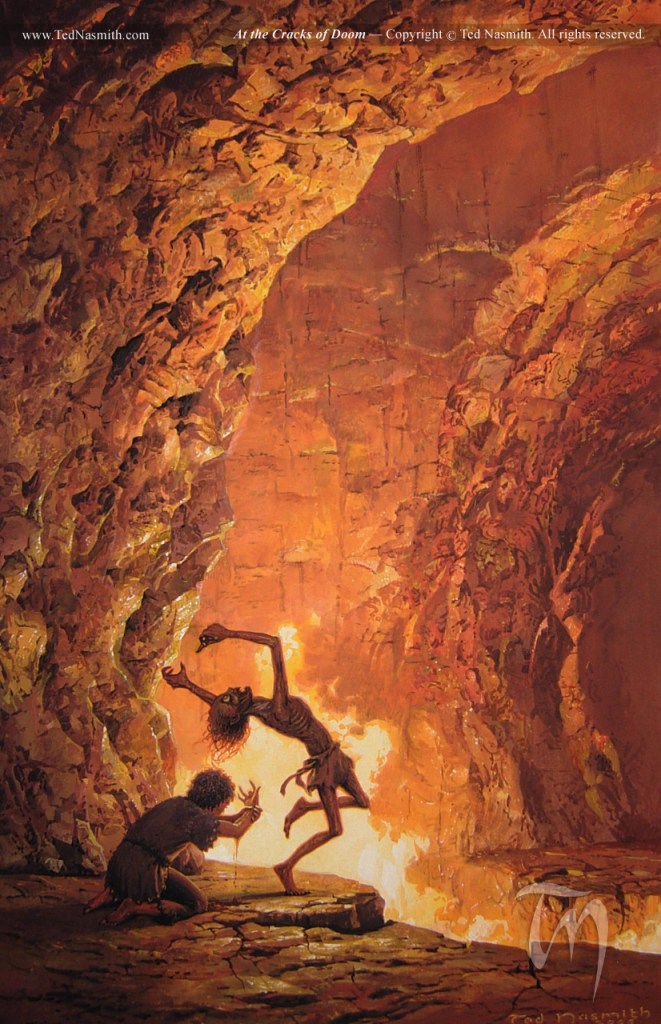

The dragon, the cup and its theft, and the consequences for Beowulf’s southern Sweden all are derived from the Old English poem.

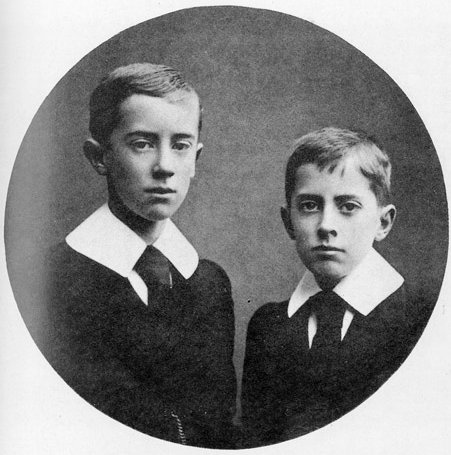

For all of this landscape of destruction described by the raftsmen, however, I would propose one further source, not something which Tolkien had read, but which he himself had experienced.

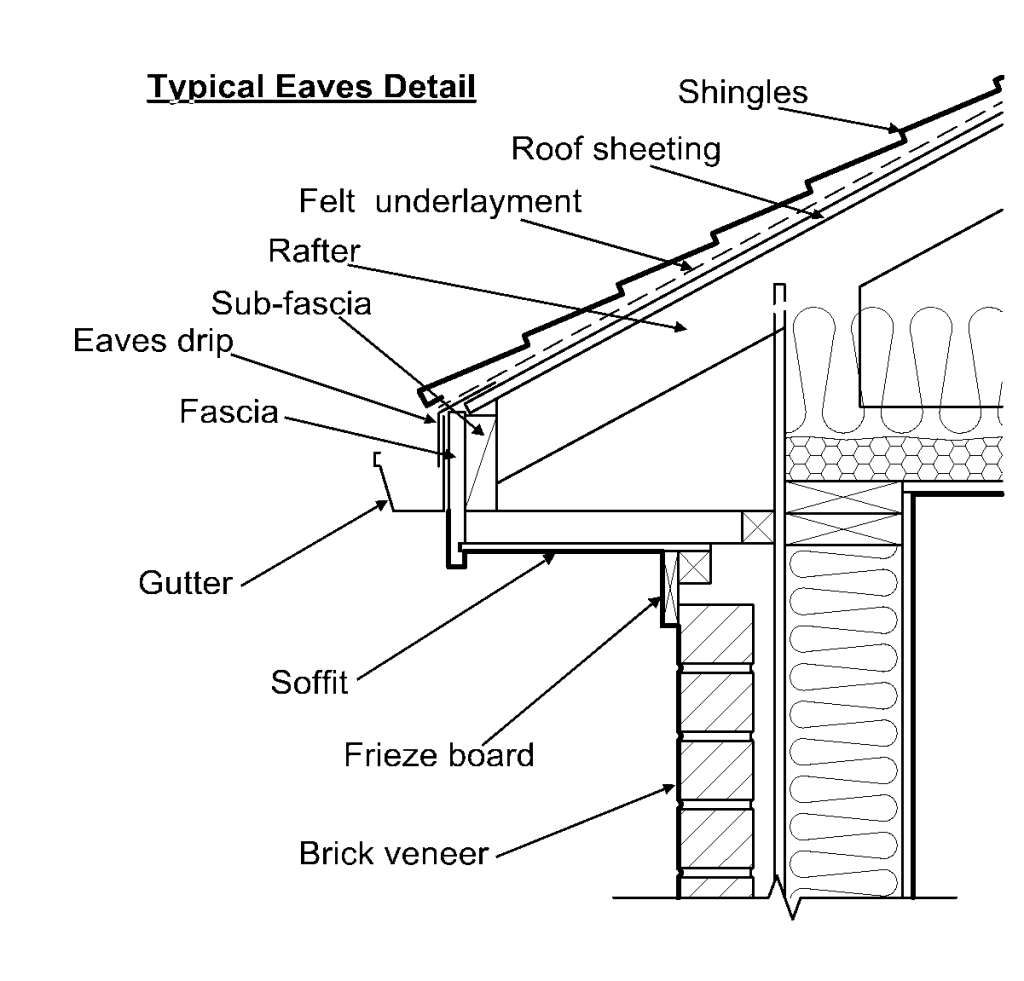

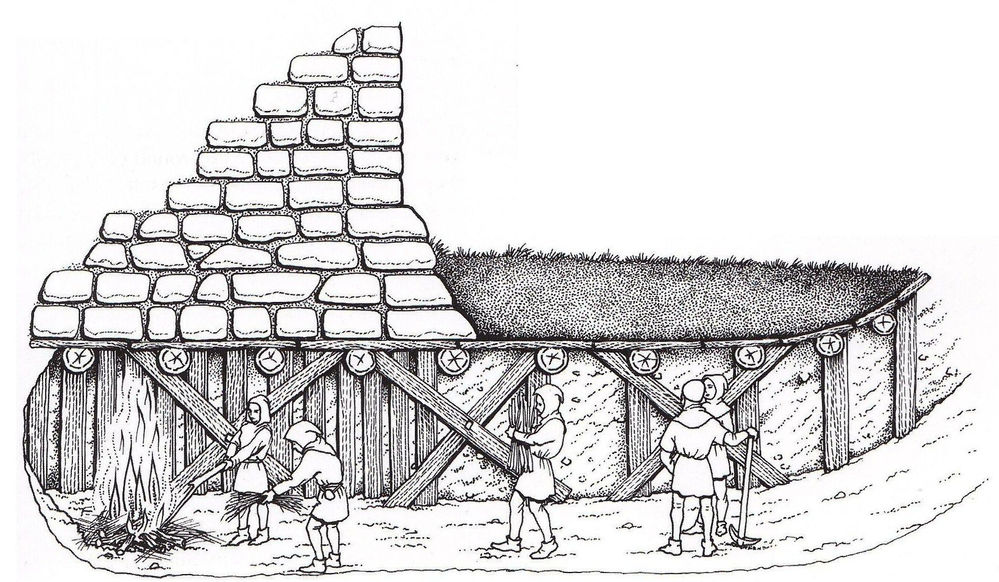

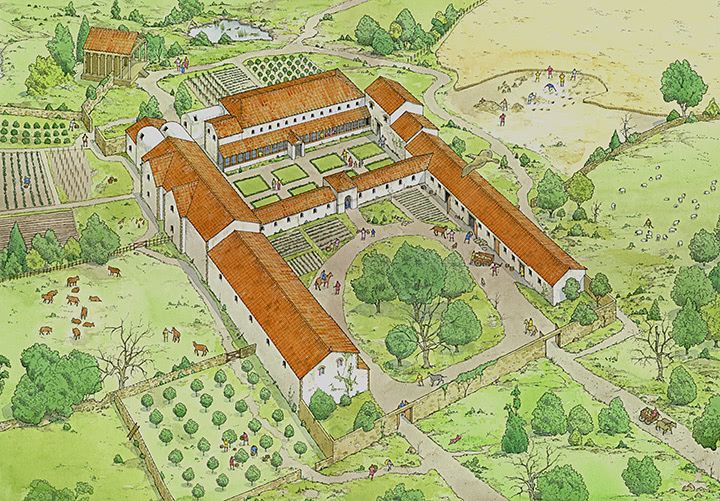

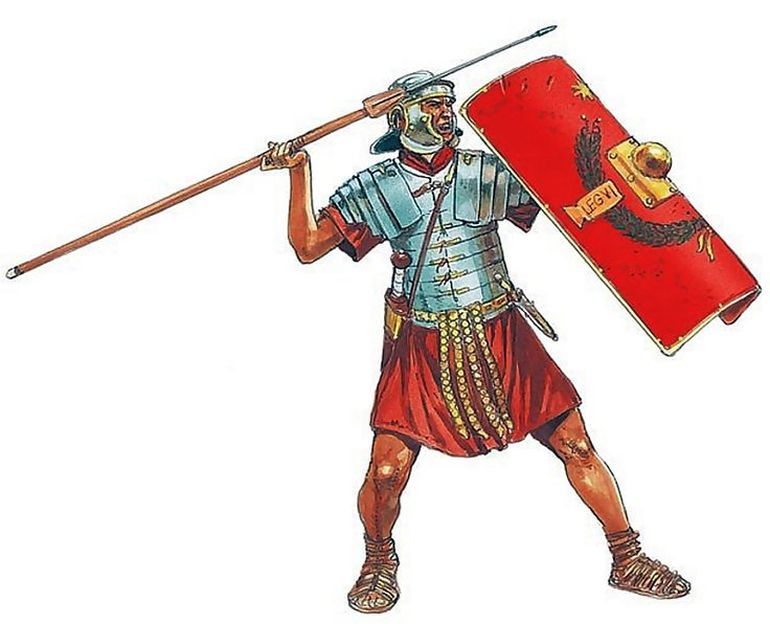

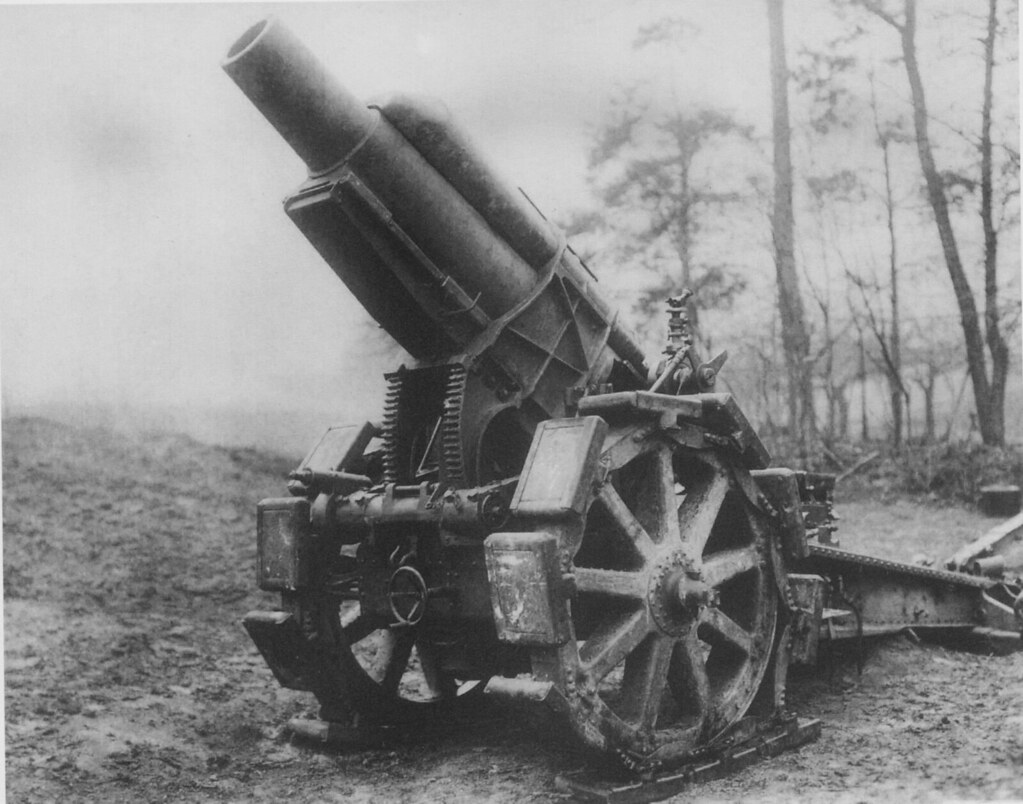

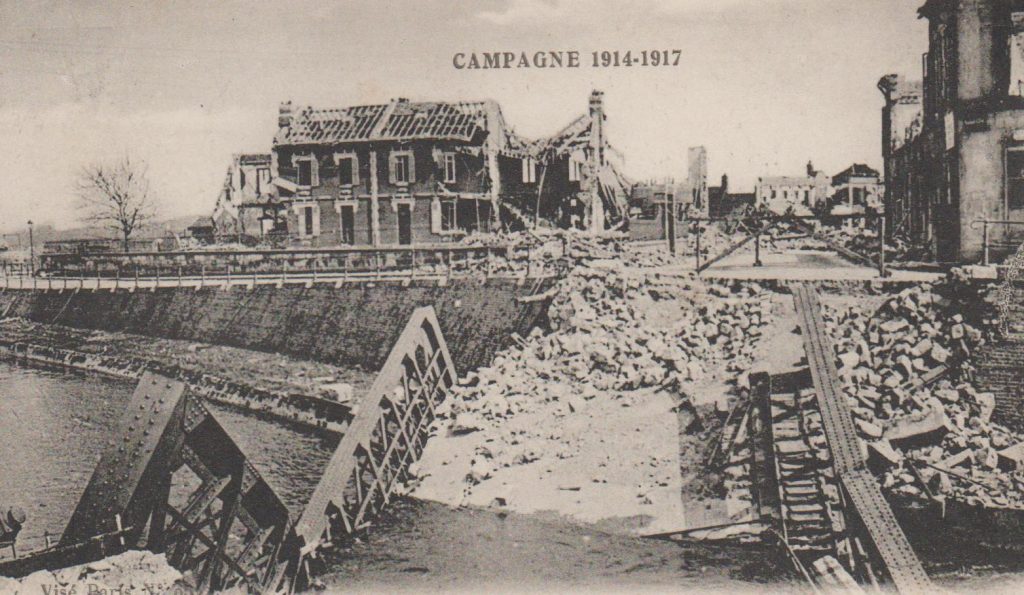

When JRRT arrived in northern France in June, 1916, just in time for the Somme offensive, the war had been going on for nearly two years in the region and the heavy artillery of the era

had done a very good job of leveling virtually everything in sight, from houses

to churches

to whole towns

to bridges

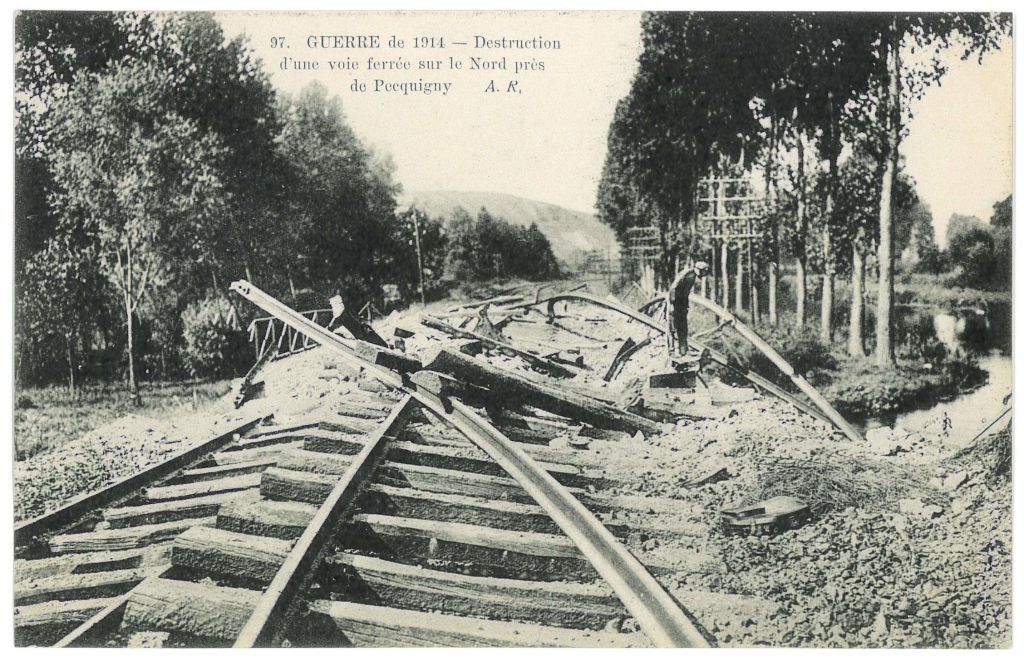

to railways,

and this was the world through which Tolkien walked for some months, till invalided out with trench fever in November, 1916.

The destruction either caused by or attributed to Smaug would seem to be everywhere in these images.

I would add, however, a prophetic element to JRRT’s description.

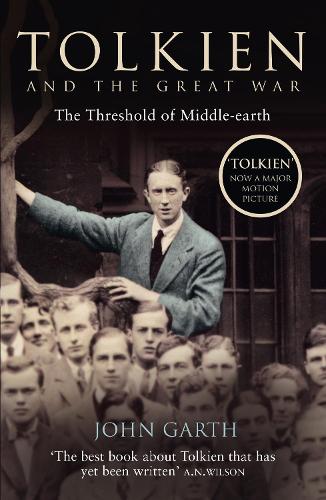

The idea of Tolkien’s Great War experiences and how they may have shaped his views on many things has become a commonplace of Tolkien studies, the seminal work being John Garth’s Tolkien and the Great War, 2003.

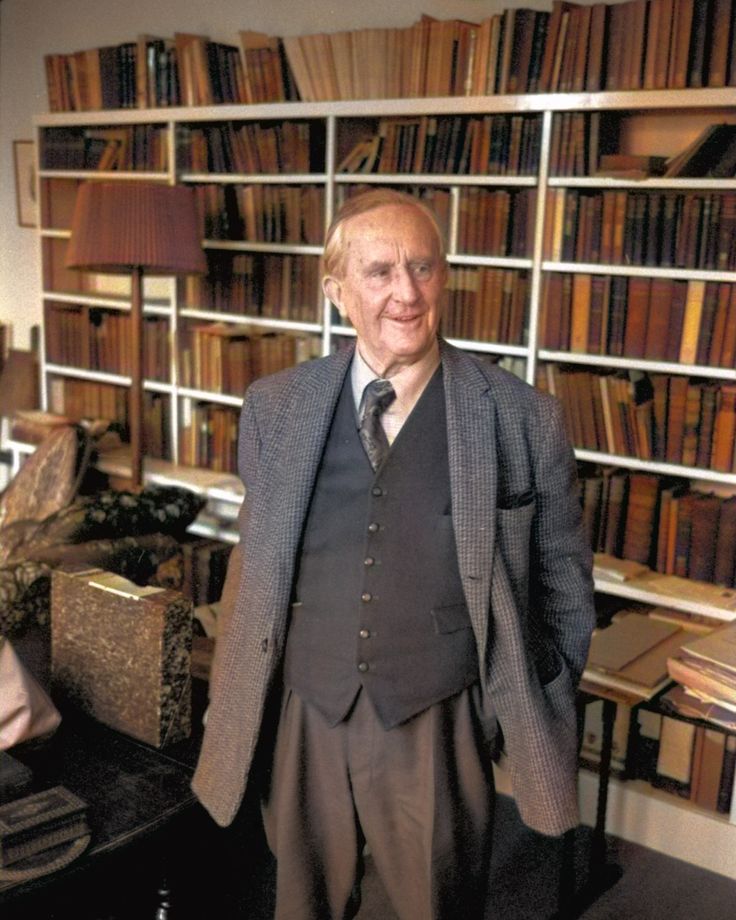

But then another war came, and, with it, many dragons flying over Britain,

bringing more fiery destruction.

Oxford escaped bombing (see: https://www.exploringgb.co.uk/blog/whywasntoxfordbombedworldwar2 ), but Tolkien could see vivid images of London and other British cities suffering terrible damage from Nazi aerial attacks from 1940 on—

and, did images like this

remind him, on the one hand, of what he had seen in the Great War, and, on the other, of what he had imagined and described from what he had seen then?

“They removed northward higher up the shore; for ever after they had a dread of the water where the dragon lay. He would never again return to his golden bed, but was stretched cold as stone, twisted upon the floor of the shallows. There for ages his huge bones could be seen in calm weather amid the ruined piles of the old town . But few dared to cross the cursed spot, and none dared to dive into the shivering water or recover the precious stones that fell from his rotting carcase.” (The Hobbit, Chapter Fourteen, “Fire and Water”)

Thanks, as always, for reading.

Stay well,

When you think of dragons, remember the Reluctant one, as well as the terrible,

And remember, as well, that, as always, there’s

MTCIDC

O

PS

If you don’t remember the Reluctant Dragon, see: https://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/35187/pg35187-images.html#Page_149