Tags

A Christmas Carol, A Visit to William Blake's Inn, Aeetes, Alexander Deruchenko, Alice and Martin Provensen, Argo, Barrow-downs, Barrow-wights, Beowulf, Bilbo, Charles Dickens, Cinderella's Dress, Colchis, Collyer Brothers, David Gwillim, dragon-sickness, Dragons, Dwarves, Ebenezer Scrooge, Eurystheus, Hera, Heracles, Hoard, hordweard, Jack Gwillim, Jane Dyer, Jason and the Argonauts, Jason and the Golden Fleece, Kinder und Hausmaerchen, Ladon, Lonely Mountain, magpie, Nancy Willard, Neolithic, Scrooge McDuck, Scythians, Ted Nasmith, The Hobbit, The Lord of the Rings, Tolkien, Treasure

Welcome, dear readers, as always.

Recently, we’ve had a couple of posts on dragons and hoards, but, having done a certain amount of research and thinking and writing, we’ve come back once again to the subject, with the question: why would a dragon want a hoard to begin with?

The earliest Western European stories we know in which dragons (or serpents—the Greek word can apply to either) are associated with valuables are:

- the 11th labor of Heracles, in which his cousin, Eurystheus, demands that Heracles bring him the Golden Apples of the Hesperides (“children of the evening star”)—which are on an island guarded by a 100-headed (in some versions of the story) dragon/serpent called Ladon

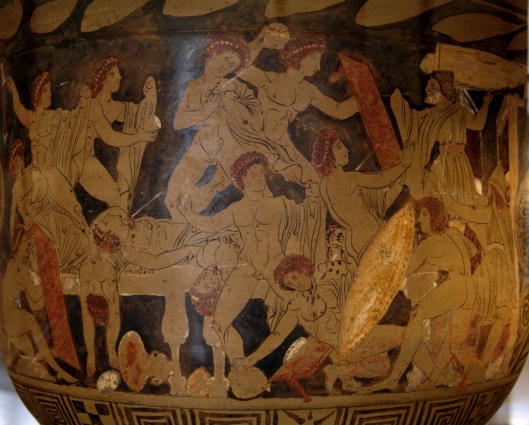

- the story of Jason and the Argo, in which Jason must bring back to Greece the Golden Fleece, also guarded by a dragon/serpent (a sleepless one this time)

In both of these stories, the dragon is the agent for someone else—Hera, in the case of the Golden Apples,

and Aeetes, the king of Colchis, in that of the Golden Fleece.

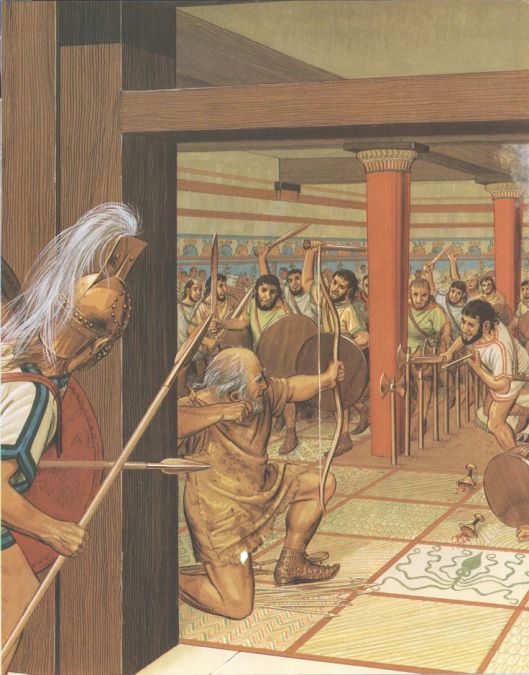

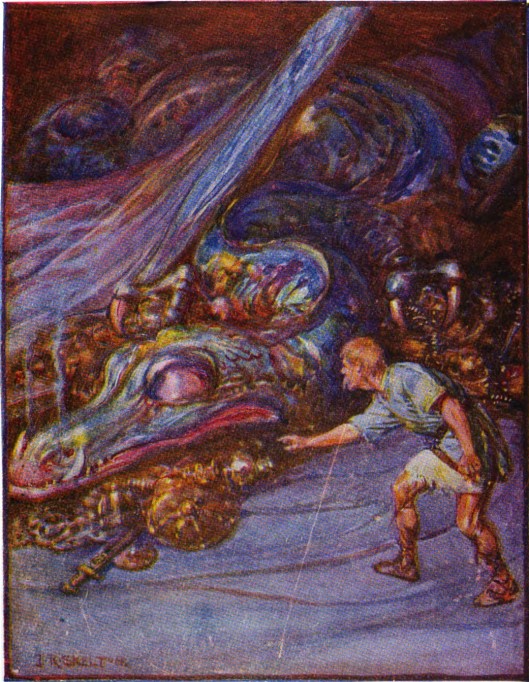

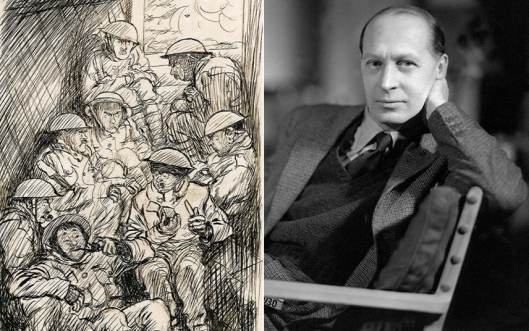

(We’ve always loved the curly beard of Jack Gwillim in Jason and the Argonauts—1963. His son, David, by the way, was a perfect Prince Hal and Henry V in BBC productions from 1979—if you can find them, we highly recommend them.)

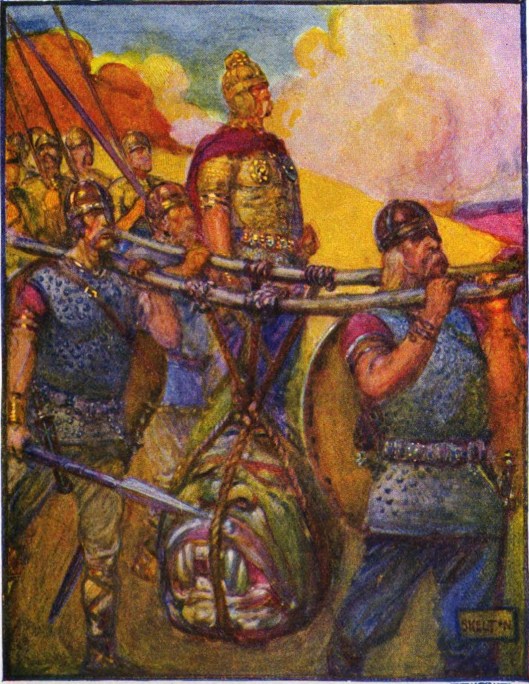

After these, we see the dragon of Beowulf.

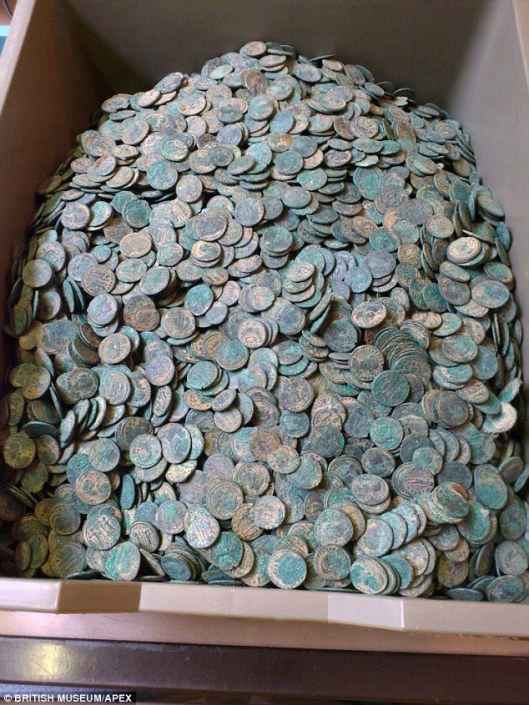

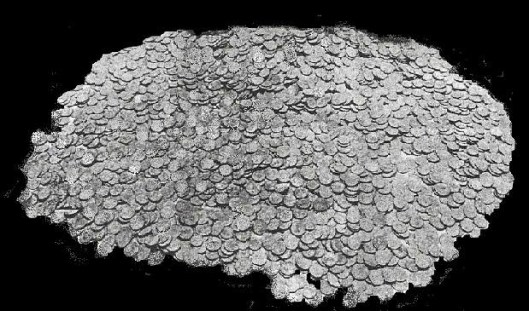

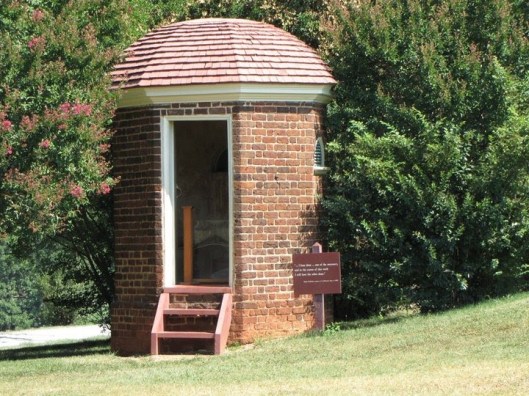

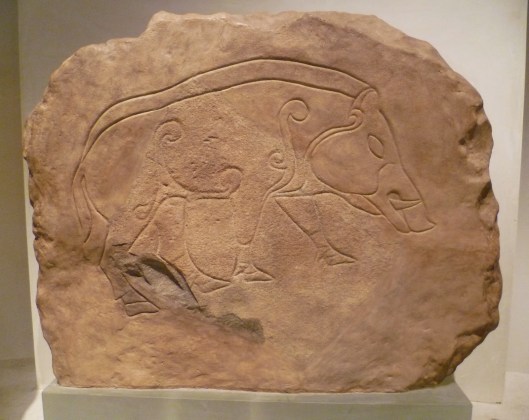

In his case, although he’s called hordweard, “hoard guardian/watchman”, we are told that he has come upon a treasure in a barrow, piled in for safe-keeping several hundred years before. Europeans in the Neolithic Period and long beyond buried high-status people in such places—like this, in Denmark.

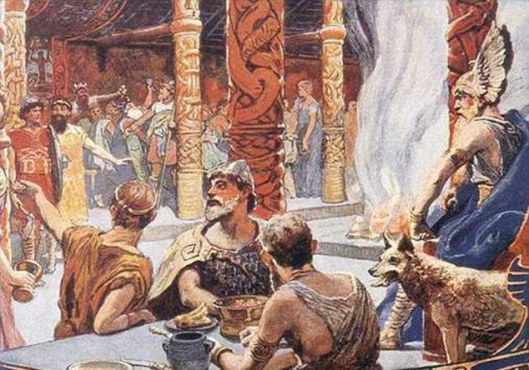

As it was the custom for high-status people to be buried with at least some of their riches, it’s easy to see how singers might be inspired to create a barrow like that of the Beowulf dragon. Some of our favorite grave goods come from the Scythians, a horse-people who once lived north of the Black Sea, and who had buried them in grave mounds with their dead.

(A wonderfully atmospheric picture by Alexander Deruchenko.)

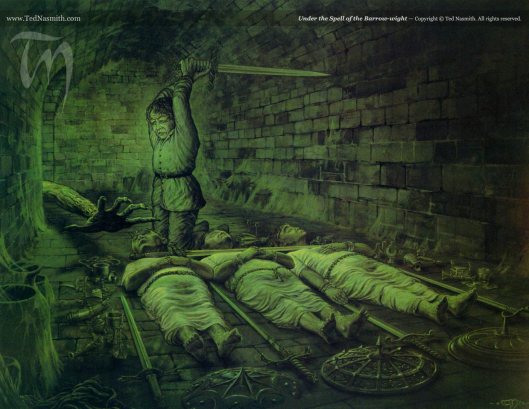

The Beowulf dragon is not the proper owner of the hoard: rather, he has taken possession (the poem may even be suggesting that dragons—or this dragon, at least– have a special affection for barrows (2270-2278), rather as the barrow wights have taken over the tumuli on the Barrow Downs, both places being much older and long-abandoned. You may remember this striking image by one of our favorite Tolkien artists, Ted Nasmith–

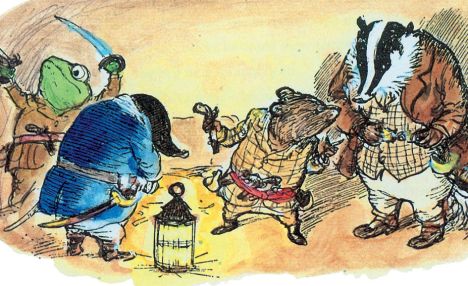

In contrast, Smaug has taken possession of the Lonely Mountain by force, burning out the rightful owners.

In both cases, however, the latest owner is very sensitive about his new property: the removal of one object, as Beowulf and Bilbo find out.

(And we can’t resist this item—it’s copy of a cup used in the 2007 Beowulf film. We don’t see that it would be very useful for drinking from, but it’s certainly fun to look at!)

It’s one thing if it’s your job to guard gold: you’re like a sheepdog with a flock. (Here’s a Maremma, in fact, with a flock.)

It’s another if you are occupying, seized or not, someone else’s gold. In the latter case, however, we are still left with our initial question: why is this important to a dragon?

Perhaps they just like the look of it. After all, Smaug seems quite proud of what he sees as a waistcoat of precious things. When Bilbo says: “What a magnificence to possess a waistcoat of fine diamonds!” Smaug replies “Yes, it is rare and wonderful, indeed.” (The Hobbit, Chapter 12, “Inside Information”) Yet there is the darker side:

“To say that Bilbo’s breath was taken away is no description at all. There are no words left to express his staggerment, since Men changed the language that they learned of elves in the days when all the world was wonderful. Bilbo had heard tell and sing of dragon-hoards before, but the splendor, the lust, the glory of such treasure had never yet come home to him. His heart was filled and pierced with enchantment and with the desire of dwarves; and he gazed motionless, almost forgetting the frightful guardian, at the gold beyond price and count.” (The Hobbit, Chapter 12, “Inside Information”)

Just seeing such wealth brought on “lust” and “the desire of dwarves” and it’s clear that this is what infects Thorin after Smaug’s death and eventually brings on the “dragon-sickness” which leads to the end of the Master of Laketown (The Hobbit, Chapter 19, “The Last Stage”). As this “lust” for beautiful, valuable things seems inherent in the dwarves, it strikes us that we might imagine dragons as somehow enablers or carriers—like anopheles mosquitoes and malaria—

rather than originators of the disease and that the name is derived from that combination of acquisitiveness and sensitivity we noted earlier and which so clearly disturbs Thorin’s judgement.

But perhaps there is something in the idea of hoarding itself. In our world, “hoarding” has come to have a different meaning, being a kind of psychological condition in which a person acquires and acquires and has lost the ability to discard anything for complex internal reasons. In literature, one might imagine that misers have something of this—think of Ebenezer Scrooge, in Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol (1843).

Or, Uncle Scrooge McDuck, from Walt Disney comics. Who, as you can see, takes this to an extreme even Dickens’ Scrooge might find a bit excessive.

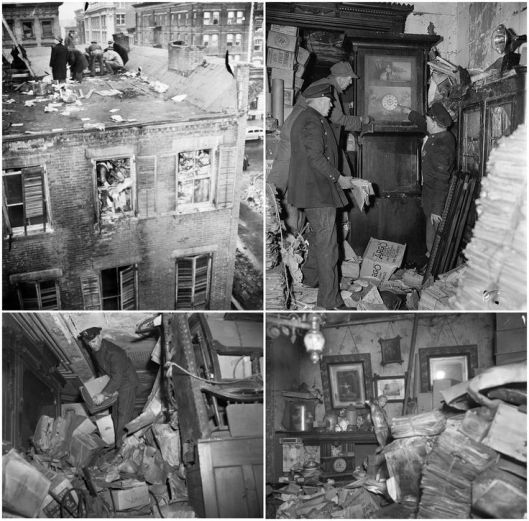

Underneath this, however, is the sad side: those who become imprisoned by their possessions, a famous case being that of the Collyer brothers in New York, whose apartment, after their joint deaths in 1947, was a subject both of curiosity and of mild horror in the New York newspapers of the time.

Is it possible that the Beowulf dragon and Smaug both suffer from this condition? Is that why the theft of a single piece from an uncountable hoard seems to mean so much?

We never want to shy away from serious subjects—after all, all of the best fantasy/adventure writers never did—but it’s an early summer day where we live—just after Midsummer’s Day, in fact, and so we’d like to end with another kind of acquisitor—the magpie.

Traditionally, magpies are famous for being attracted to—and collecting—shiny objects. Our favorite magpie story, however, isn’t about obsession, but about generosity. It’s a beautiful children’s book by Nancy Willard and Jane Dyer, entitled Cinderella’s Dress.

In this book, told in light, easy verse, we see a magpie couple as fairy godparents for Cinderella, using their cache of shiny things to—but we’ll leave that to you to discover (although the title is a bit of a give-away). Here’s another page to tease you…

Thanks, as ever, for reading.

MTCIDC

PS

Another Nancy Willard book you might enjoy is A Visit to William Blake’s Inn (1981), illustrated by Alice and Martin Provensen.

(As usual with so many old and established things, there is argument over where the word “penny” comes from. Personally, we’ve always imagined that it’s an English diminutive of a Brythonic word—as it exists today in Welsh—“pen” = “head”, the idea being that coins had portrait heads on them. Certainly some pre-Roman British coins had them

(As usual with so many old and established things, there is argument over where the word “penny” comes from. Personally, we’ve always imagined that it’s an English diminutive of a Brythonic word—as it exists today in Welsh—“pen” = “head”, the idea being that coins had portrait heads on them. Certainly some pre-Roman British coins had them