Tags

Anglo-Scots border, Black Middens Bastle, blackmail, Border Marches, Border Reivers, Border Wardens, Charlemagne, Debatable Lands, Emyn Beraid, Fairbairns, Hadrian's Wall, Hermitage Castle, hot trod, John Philip Sousa, Marca Hispanica, Marches, Monty Python, Offa's Dyke, Robert Carey, Scots Dike, Smailholm Tower, Ted Nasmith, The Liberty Bell, The Lord of the Rings, The Shire, Tolkien, Tower Hills, West March

Welcome once more, dear readers.

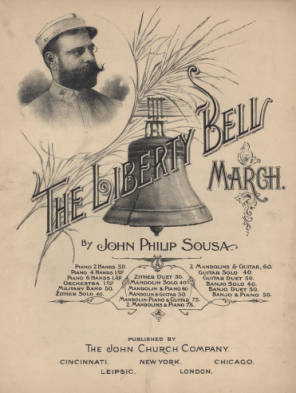

In this posting, we want to return to a recent one about “marches”—that is, not pieces for military bands (although we are partial to those of John Philip Sousa—1854-1932–

especially “The Liberty Bell”—1893—

mostly because it was used by Monty Python. We provide a link here for what might have been its first recording, by the “Edison Grand Concert Band” in 1896. Watch out for the big foot!)

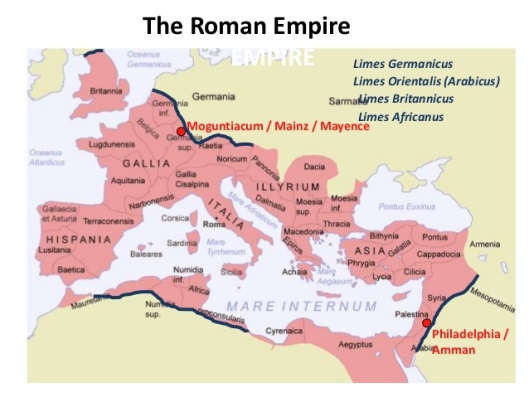

but border areas, usually sensitive ones, which might have been militarized, like that at the southern edge of Charlemagne’s empire.

This, the Marca Hispanica, existed as a buffer state between the Moorish Caliphate to its south and the Holy Roman Empire to the north.

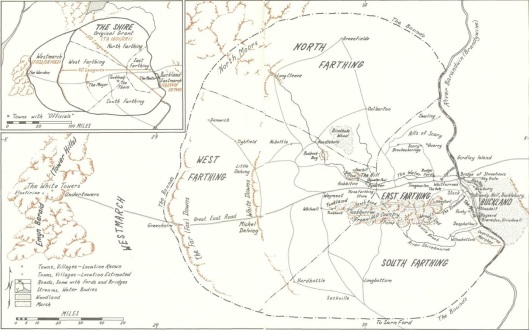

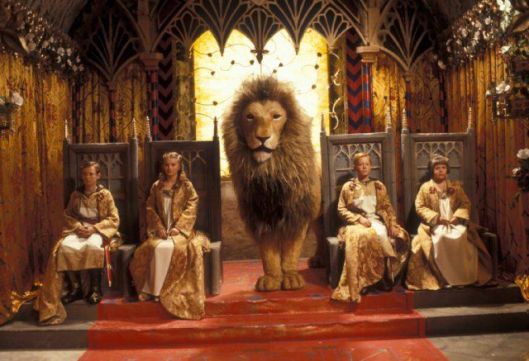

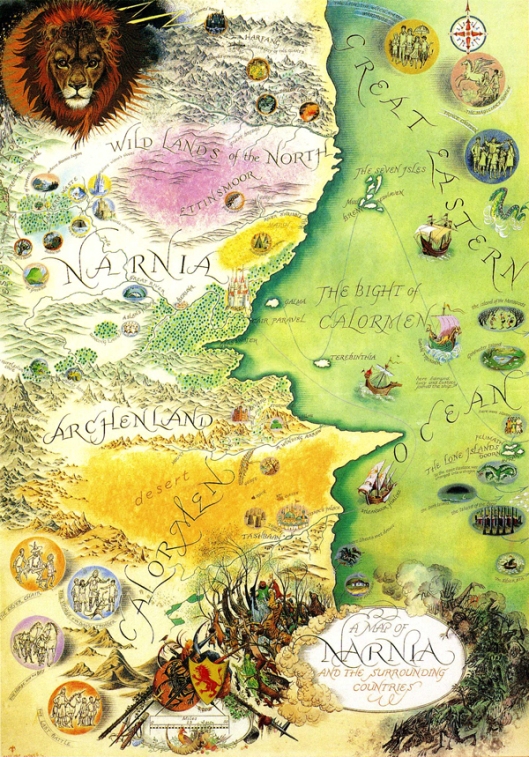

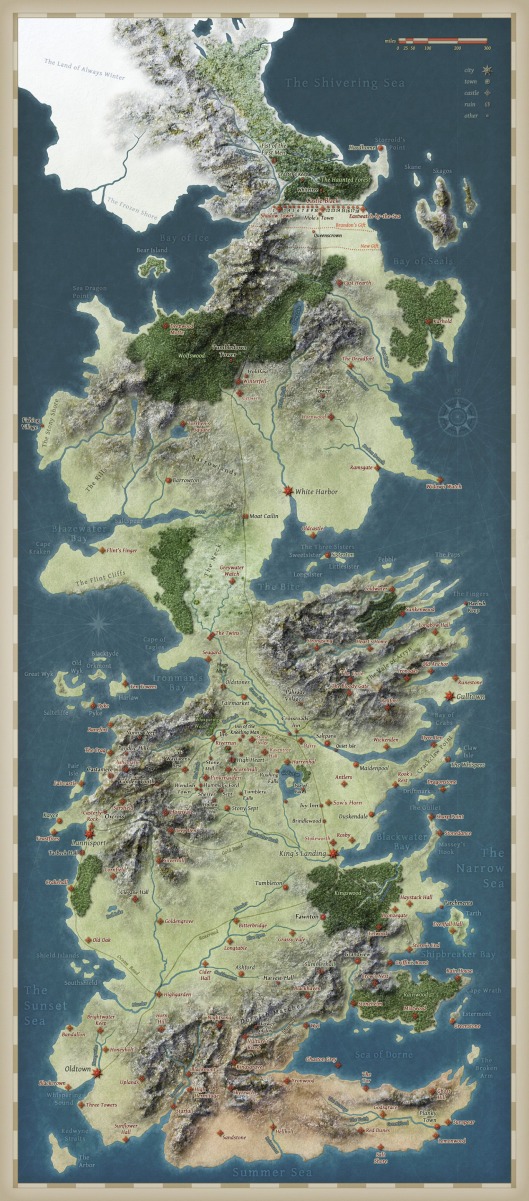

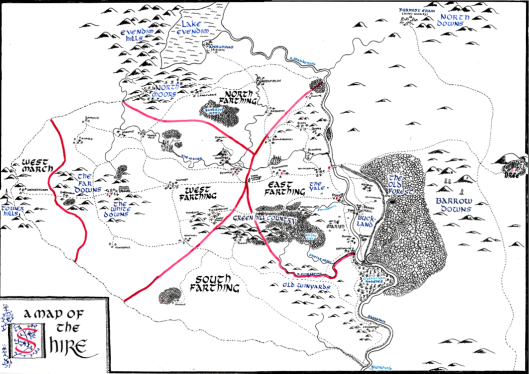

In contrast, we have the West March, to the west of the Shire, as we’ve discussed before.

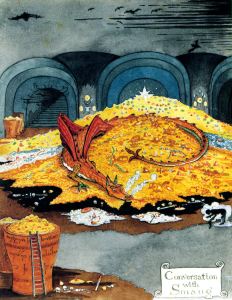

At its far western edge are the Tower Hills (here illustrated by one of our favorite Tolkien artists, Ted Nasmith)

on which are perched three white towers, described in the Prologue to The Lord of the Rings:

“Three Elf-towers of immemorial age were still to be seen on the Tower Hills beyond the western marches. They shone far off in the moonlight. The tallest was furthest away, standing alone upon a green mound. The Hobbits of the Westfarthing said that one could see the Sea from the top of that tower; but no Hobbit had ever been known to climb it.” (Gandalf adds to this that there was a palantir, Elendil’s Stone, located there—The Two Towers, Book Three, Chapter 11, “The Palantir”.)

The difference is, those towers don’t seem defensive and the West March is not a military zone—although it is the site of Hobbit-expansion, as Appendix B tells us:

“1452 The Westmarch, from the Far Downs to the Tower Hills (Emyn Beraid) is added to the Shire by the gift of the King. Many hobbits remove to it.

1462 …the Thain makes Fastred Warden of Westmarch. Fastred and Elanor make their dwelling at Undertowers on the Tower Hills, where their descendants, the Fairbairns of the Towers, dwelt for many generations.”

Talk of marches and wardens and towers, however, immediately brought to mind for us something from our world (doesn’t it always?).

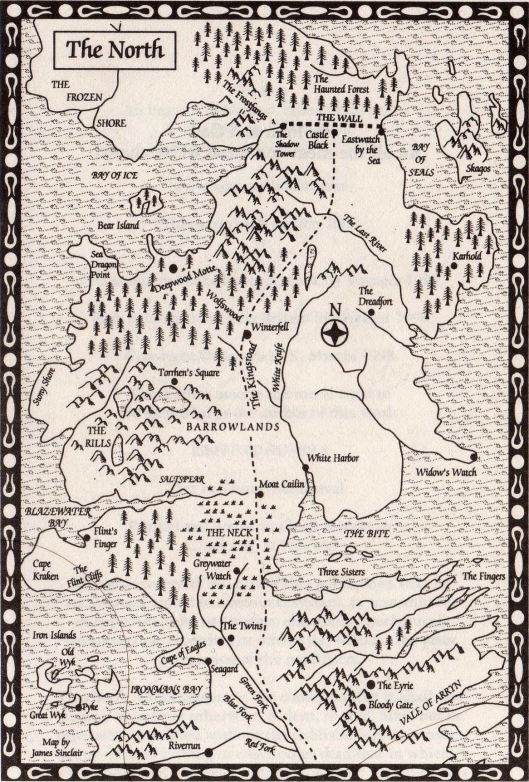

This is the border area between England and Scotland, an area of conflict for several centuries, but culminating in the struggles of the 16th century.

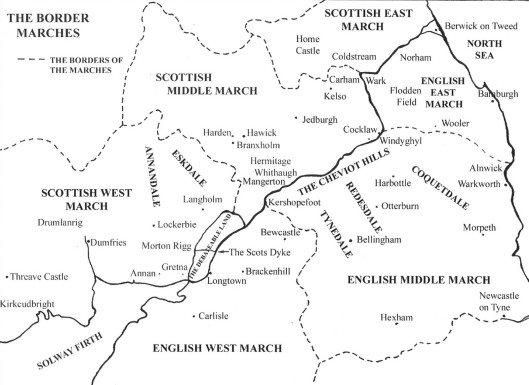

The border area had been divided, on both sides, into three marches, with a subset for that area on the southwest side called the “Debatable Lands”, because both England and Scotland claimed it. In 1552, the decision was mutually made to put up an earthen barrier, the so-called “Scots Dike”, to split it.

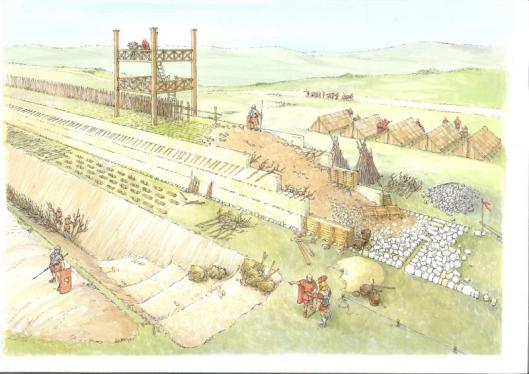

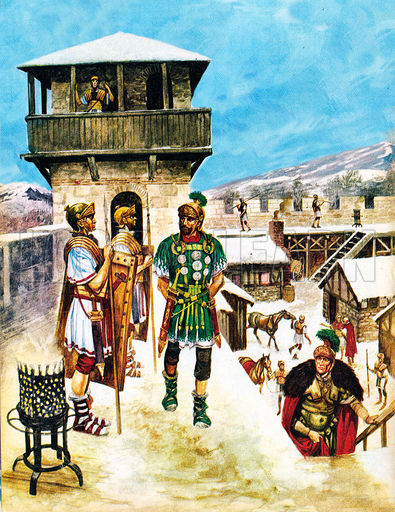

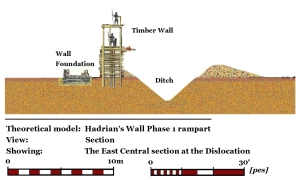

Unlike Hadrian’s Wall, farther to the south, with its system of walls and towers and gates and little forts and big army camps, this was never an elaborate military structure, or even like Offa’s Dike between England and Wales,

but simply a boundary marker in low-lying land (and only 3.5 miles long– 5.6km).

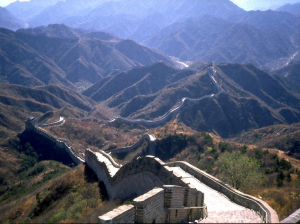

When it came to the border towards the east, and the center of the region and beyond, however, the land rises into the characteristic twisty hills with long, narrow valleys.

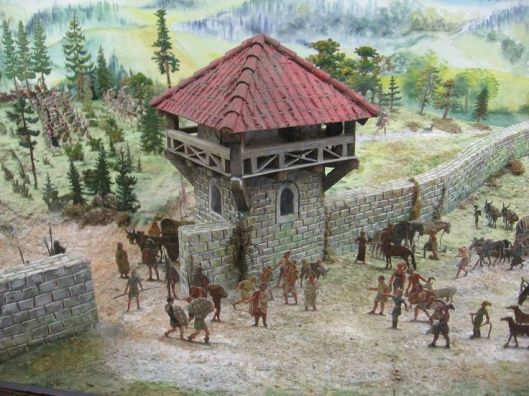

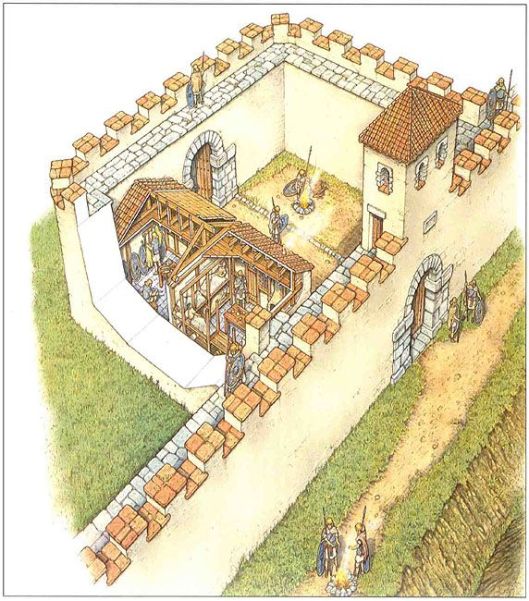

In this wild world, there are no long walls, of stone, wood, or earth to protect anyone, but castles, towers, and fortified farmhouses called bastles (possibly from the same root as “Bastille”?). Here we see Hermitage Castle, Smailholm Tower, and Black Middens Bastle.

Although we see these now as gaunt ruins, we should always imagine them—as in this reconstruction of Smailholm—as living spaces, as well as refuges in an often lawless land.

One has only to see the thick walls of a bastle and, originally, no door at ground level (stairs appear to be a later convenience for a more peaceable time), to imagine the danger from reivers, raiders from either side of the Anglo-Scots border and sometimes, as there was a certain amount of intermarriage, from both.

As can be seen in this reconstruction, these walls might be all that would stand between the inhabitants and destitution or even death, should the reivers come raiding.

There was also the possibility of buying them off, by paying them blackmail, a word whose origin is contested, but whose purpose is clear: protection money. If you paid them, in coin or cattle, you were safe—at least until the price went up.

Curbing such behavior was the job of the Border Wardens, there being six, one for each March on each side of the border. Theirs was a difficult job: too much territory, too few men, and too few resources to back them up. Wonderfully, one of these Wardens, Robert Carey, has left us a memoir, which is available on-line: memoirsrobertca00orregoog.

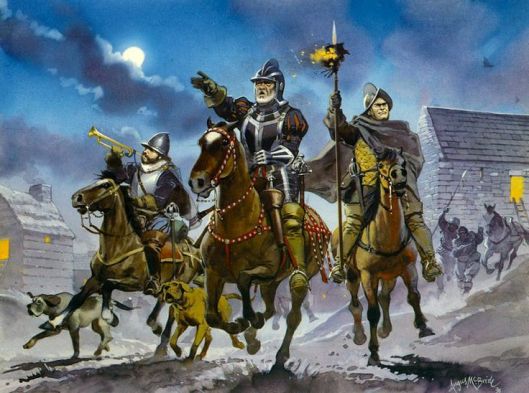

If you were attacked and you survived, you might send word to the Warden or one of his officers, who could organize a posse to pursue the raiders. By law, all able-bodied locals were supposed to turn out to help when the organizer—Warden or officer—rode by with trumpeter and a rider who carried a flaming bit of peat on his “staff” (local word for “lance”).

This was called the “hot trod” and, under its conditions, the pursuers were allowed to cross the border. Such occasions could be very dangerous, however, as those raiders would be chased back across their own territory, giving them the chance to delay or destroy those in pursuit in an ambush on familiar ground.

We were originally drawn to this part of the world and of Anglo-Scottish history because of our interest in the musical literature of the region, the so-called “border ballads”, and, in our next, “Bordering (.2 Blackmail, Battle, and Song”) we’ll talk a bit about them—and perhaps a bit more about borders and heroic behavior, as well.

Thanks as ever, for reading!

MTCIDC

CD